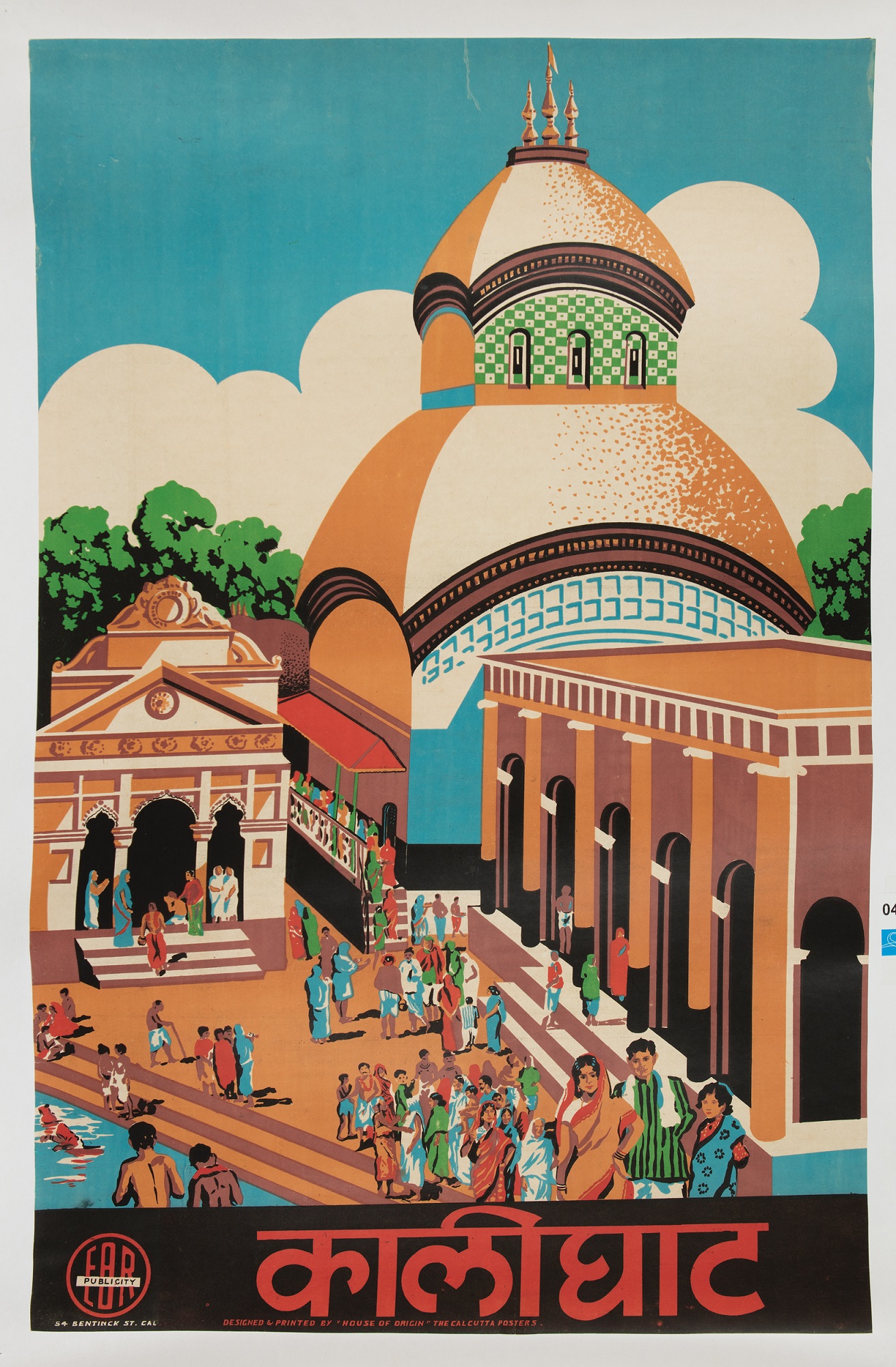

Images of Kalighat: Views around a temple neighbourhoodThe Editorial Team February 01, 2024 What is the story of the Kalighat temple and its neighbourhood? And why did it need to be ‘modernised’? The Kalighat Kali Temple is a Hindu temple in Kalighat, Kolkata, dedicated to the Hindu goddess Kali. It is one of the 51 Shakti Peethas in eastern India. The temple has a long history, with references dating back to the fifteenth century. The present structure of the temple was completed in 1809 under the patronage of the Sabarna Roy Choudhury family. This has provided the ground—legal as well as political—to ‘decolonise’ the history of Kolkata, with the family making legal claims to be recognised as the ‘original’ founders (and settlers) of the city before the arrival of Job Charnock in the late seventeenth century. |

Unidentified artist (Kalighat pat)

Collection: DAG

|

The temple is believed to be one of the most important Shakti Peeths. In the context of Kali worship and Hindu mythology, a Shakti Peeth is a sacred place associated with the Goddess Shakti, particularly in her various forms such as Kali, Durga, or Parvati. The term ‘Shakti’ refers to the divine feminine energy or power, and ‘Peeth’ means a sacred spot or shrine. Each Shakti Peeth is associated with a specific part of Sati's body and has its own significance and mythology. Devotees of the Goddess visit these shrines to seek blessings and offer worship. The temple's history is also associated with various legends, including the discovery of a human toe-shaped stone structure in the Bhagirathi River by Atma Ram. |

|

Unidentified Artist Shiva and Sati (detail) Oil on canvas, 1939, 36.0 × 26.0 in. Collection: DAG |

Unidentified artist (Kalighat pat)

Collection: DAG

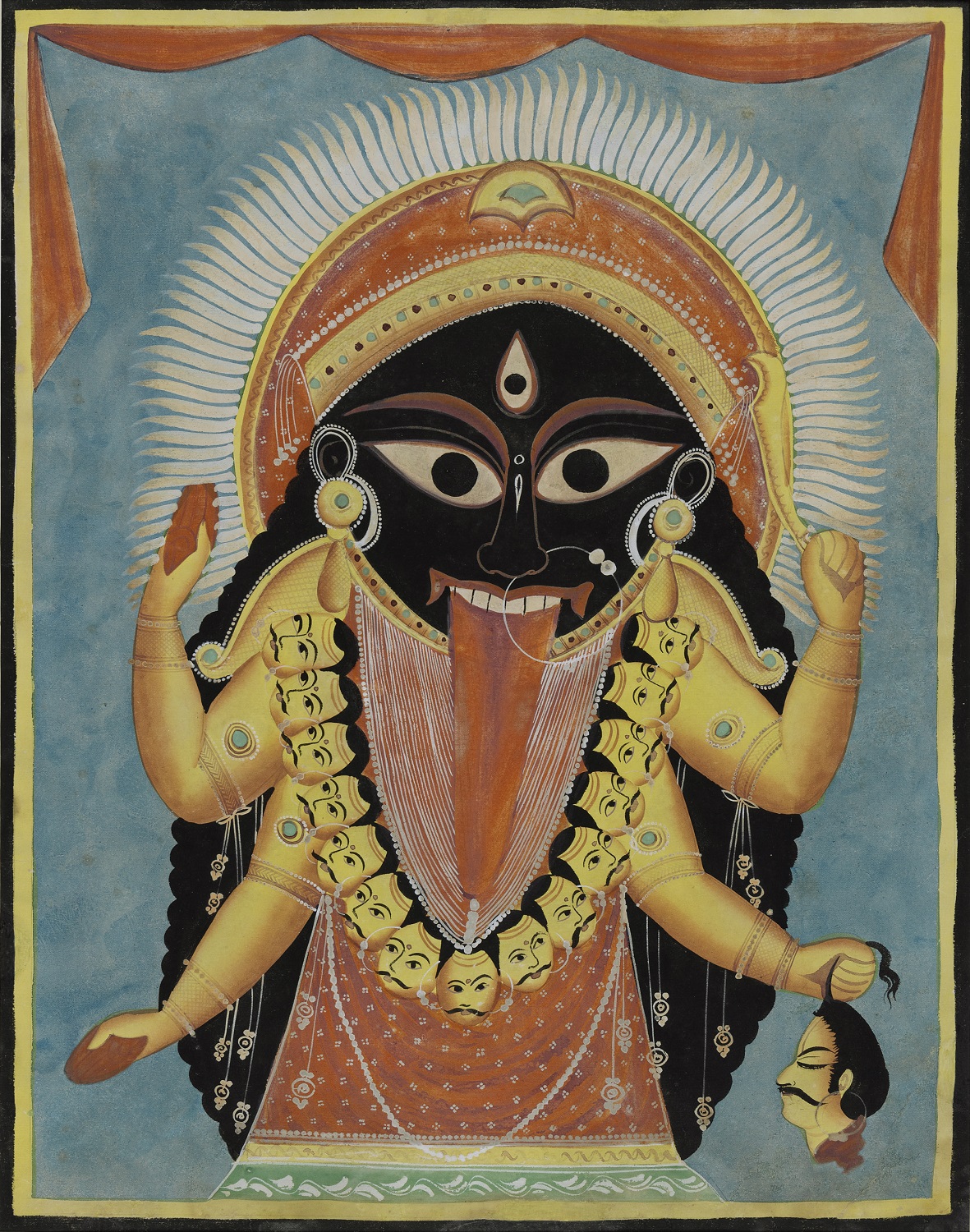

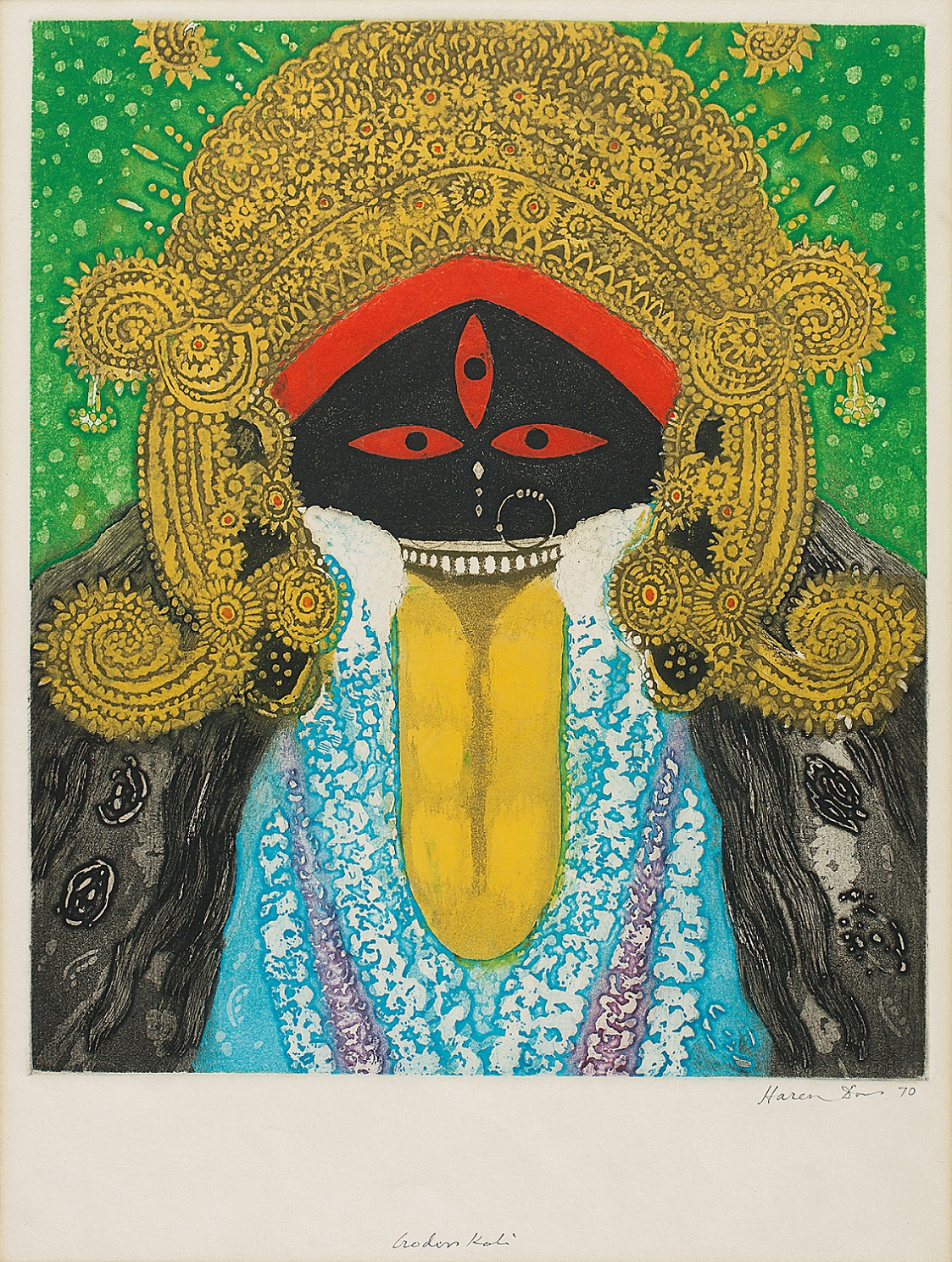

The temple is known for its unique image of Kali and is a significant pilgrimage site for devotees of the goddess. In the famous artworks produced by the patuas (painters) of Kalighat, who had settled in the neighbourhood in the nineteenth century, we see depictions of the goddess usually housed in the familiar form of the Kalighat temple. The painters settled in the neighbourhood for its attractive commercial opportunities, with the site becoming a major pilgrimage destination for devotees. The temple and its neighbourhood remained a source of inspiration for artists throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. |

|

According to legend, the origin of the Kalighat Temple is linked to the story of Sati, the consort of Lord Shiva. In Hindu mythology, Sati, the daughter of King Daksha, married Lord Shiva against her father's wishes. Daksha organized a grand yagna (ritual sacrifice) but did not invite Sati and Shiva due to his disdain for Shiva. Despite Shiva's advice, Sati attended the yagna, where she was insulted by her father. Unable to bear the humiliation, Sati immolated herself in the sacrificial fire. Enraged by Sati's death, Shiva carried her charred body across the universe in a frenzied dance of destruction, known as the Tandava. To stop him and save the world from annihilation, Lord Vishnu used his Sudarshan Chakra (divine discus) to dismember Sati's body. As Sati's body parts fell to the earth, they became sacred places known as Shakti Peethas, where devotees worship the divine feminine energy. |

|

|

Unidentified Artist

Kalighat

Chromo-lithograph on paperpasted on canvas

Collection: DAG

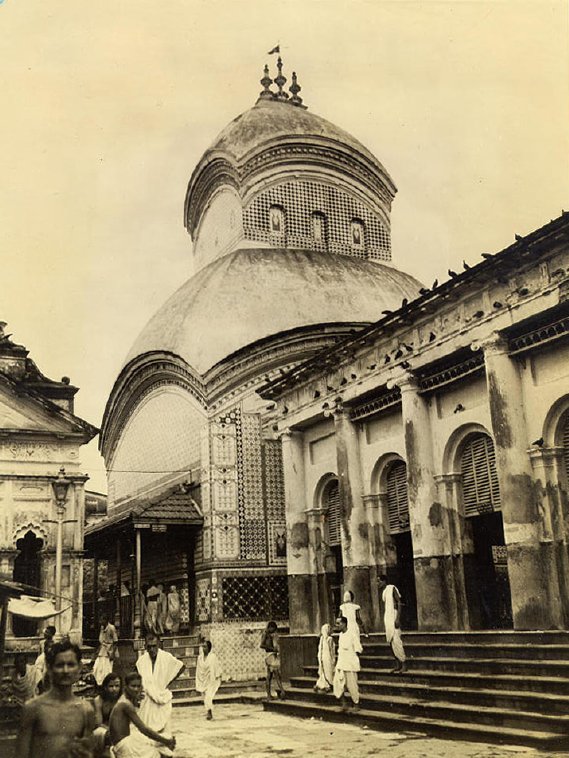

Kalighat neighbourhood

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Kalighat temple

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

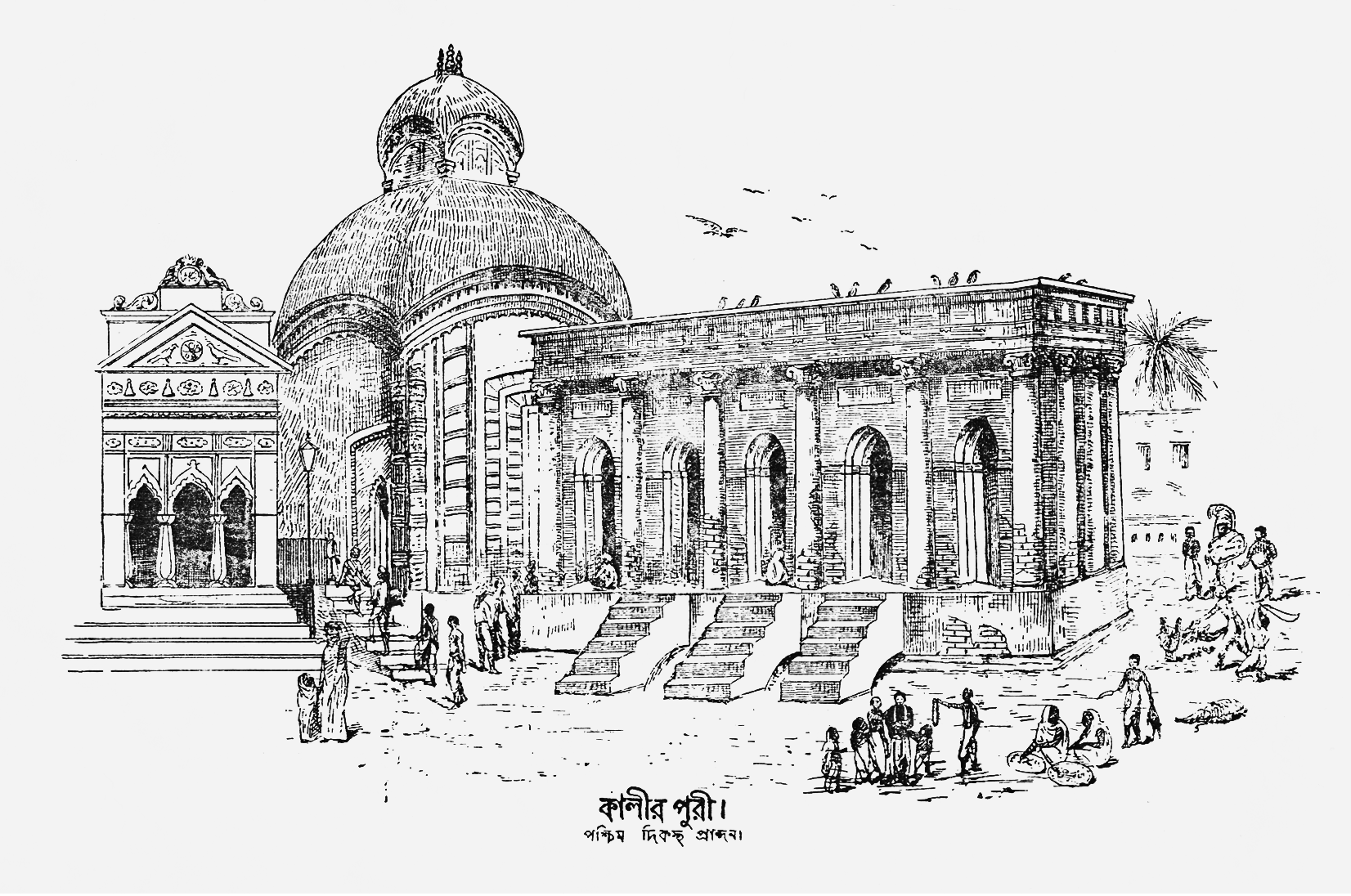

One of these sacred sites is believed to be where the toes of Sati's right foot fell, giving rise to the Kalighat Temple. It is said that the original structure of the temple was established by a devotee named Kalapahad in the fifteenth century. Over time, the temple has been renovated and expanded, becoming one of the most prominent centres of Kali worship in India. The Kalighat Kali Temple is a classic example of Bengal architecture, characterized by a four-sided building with a truncated dome and a smaller identically-shaped projection capping the domed structure. Each sloping side of the roof is referred to as a ‘chala’, and the temple is designated as a ‘chala temple’. The two roofs bear a total of eight separate faces, and the stacked, hut-like design is common for Bengali temples. The temple's outer walls are decorated with a diamond chessboard pattern of alternating green and black. The unique architecture of the temple, with its distinct Bengali style, makes it a significant cultural and religious landmark in West Bengal. |

|

The primary shrine houses the revered idol of Goddess Kali, crafted from black stone and adorned with gold and silver. Additionally, there is an image of Lord Shiva fashioned in silver. The idol of Goddess Kali is distinguished by three striking yet intense eyes, a lengthy gold tongue, and four hands, all fashioned from gold. Among these hands, two grasp a scimitar and the severed head of the asura king 'Shumbha,' symbolizing divine knowledge and the conquest of human ego, respectively. The remaining two hands depict the gestures of blessing, signifying protection and guidance for devotees, both in the present life and beyond. Each year, on the auspicious day of snan-yatra, the goddess undergoes a ceremonial bath, conducted by priests who cover their eyes with cloth during the ritual. |

|

|

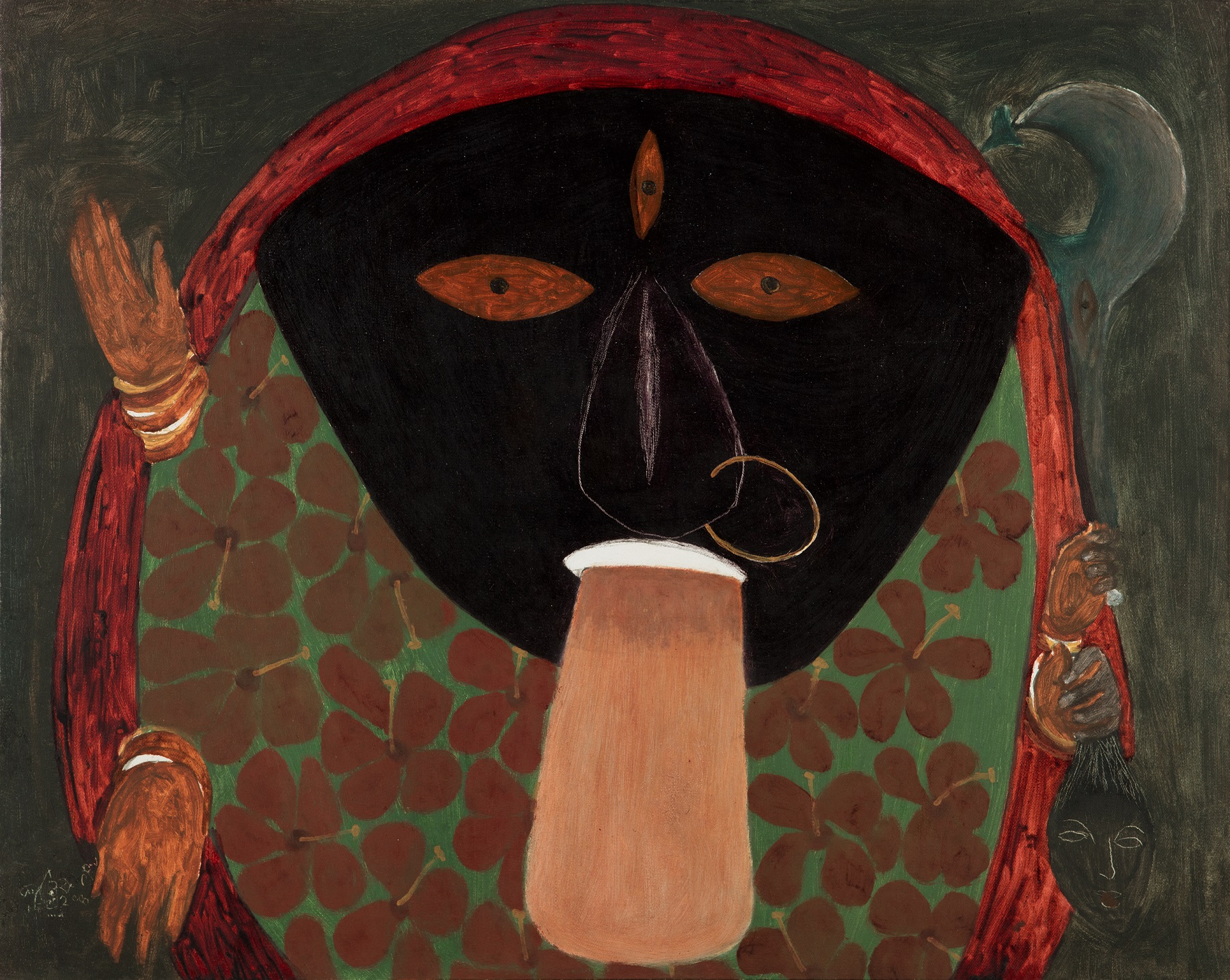

Unidentified Artist (Kalighat Pat)

Dakshinakali

Watercolour and gouache on paper, late 19th century, 19.5 × 15.5 in.

Collection: DAG

Drawing of Kalighat temple

A Commentary on the land of Kali

Image courtesy: Surjyakumar Chattopadhyay

The bathing ghat at Kalighat

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Originally, the Kali idol consisted solely of her visage, later embellished with gold and silver tongue and hands. Another representation of the goddess, known as Kalika murti, remains secluded within the temple, inaccessible to the public and even the priests. This hidden image, believed to be naturally formed, is considered the self-manifested form of Kalika, originating from one of Sati's toes. Concealed within the pedestal of the main Kali idol, this adirup (eternal form) symbolizes primal power. Adjacent to the temple stands the Nat-mandir, providing a direct view of the deity. Nearby are two sacrificial altars featuring the murti of Radha-Krishna. In the southeast corner lies the sacred tank, revered for its purifying waters akin to the Ganges, believed to grant the boon of progeny. Two queues form for darshan, one leading to the inner sanctum (Garbha-Graha or Nijo-Mandir), and the other offering darshan from the verandah (Jor-Bangla). |

Haren Das

Goddess Kali

Coloured etching on paper

Collection: DAG

The depiction of Kali in this temple deviates from conventional Bengal styles. Crafted from touchstone by saints Brahmananda Giri and Atmaram Giri, the idol features three large eyes, a gold tongue, and four hands wielding a sword and a severed head. These symbols represent the pursuit of divine knowledge to overcome human ego, essential for attaining enlightenment. The remaining hands extend blessings to devotees, emphasizing spiritual protection and grace. |

|

In spite of its sacred origins, Kalighat, the temple and its neighbourhood, was not always held in the highest regard—either by the British colonial administration, who were also motivated in writing histories of the city with themselves as the protagonists, starting with the ‘founding’ figure of Job Charnock—or by the city’s indigenous elites. As the scholar Deonnie Moodie has written, ‘This temple, which is dedicated to the dark goddess Kali, who accepts animal sacrifice, and is situated in a neighborhood inhabited by priests and sex workers, has been roundly critiqued by elites throughout its history for representing superstition and backwardness. This was especially true when Calcutta was the capital of the British Empire in India. Kalighat epitomized for colonialists, Orientalists, Christian missionaries, and Hindu reformers alike everything that was wrong with temple Hinduism. The most studied of Calcutta’s colonial middle classes the likes of Rammohan Roy, Rabindranath Tagore, and Vivekananda—ignored or denounced Kalighat. They worked to reform Hinduism by expunging it of places like Kalighat and the practices of image worship and animal sacrifice that accompanied them. This temple still represents backwardness for many middle-class Hindus who decry its rituals as superstitious, its administration disorderly, and its physical state messy and chaotic.’ |

|

|

Unidentified Artist (Kalighat Pat)

Collection: DAG

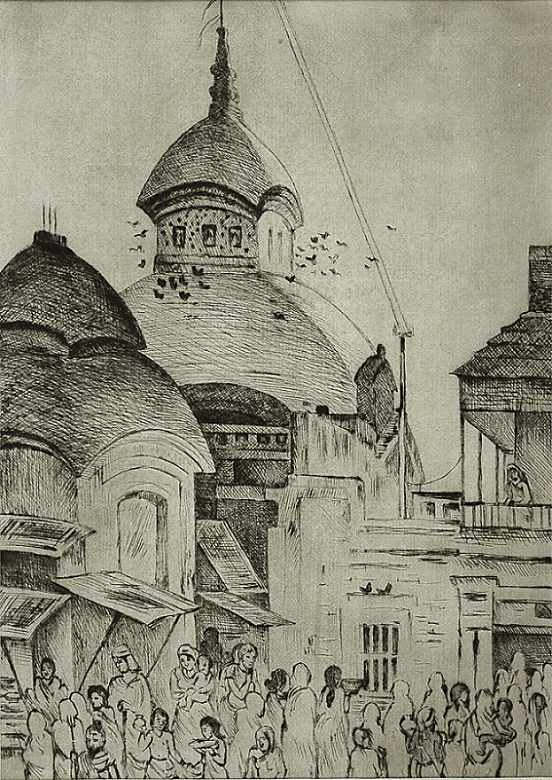

Ramendranath Chakravorty

Untitled

Drypoint on paper 9.2 X 6.5 in.

Collection: DAG

According to a guidebook published in 1882:

|

|

Even as middle-class Indian historians were writing acceptable Hindu histories for the Kalighat temple, the narrative of its emergence from the dark and wild entanglement of the forest proved a challenge to their claims of modernisation. |

|

|

The Kalighat temple in the 1940s

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Kartick Chandra Pyne

Kali

Oil on canvas

Collection: DAG

Place-making became an essential trope for these acts of reclamation, giving the neighbourhood of Kalighat a special significance in the history of the goddess. Moodie writes, ‘The formulation of Kali lying at the center of a kṣetra is noteworthy given the way in which this term has historically been deployed in Sanskrit literature. As Sontheimer writes, ‘kṣetra literally means ‘field’ or ‘area’ and refers to ‘inhabited, well-settled space with regular plough agriculture’. It is often juxtaposed with the vana or araṇya, which refers to ‘wild space’, ‘forest’ or jungle which harbours the ‘hermitage’, the tribals, the saṃnyasi and the asrama,’ where normal rules of society are not enforced’. The vana is home to cremation grounds where Siva and Kali typically reside. When towns are built, these deities stand at the borderline between vana and kṣetra to protect the kṣetra. Our authors (referring to the Indian historians, including Gaur Das Bysack and Surjyakumar Chattopadhyay) were thus inverting the Brahminical norm. Their kṣetra is not marked by human settlement and agriculture. It is civilized even though it is forested and uninhabited because Kali is present, as are her worshipers.’ |

|

Thus, the Kalighat temple was coopted into a narrative of modernity and progress—a crucial project for Indian devotees who wished to demonstrate their willingness to be modern, without giving up their claims on tradition. Its neighbourhood and the temple structure bear the traces of these complex struggles, even as pilgrims make the place what it once was and continues to be. |

|

|