Illustrating Durga: Surveying the Sharodiya Specials in Bengal

Illustrating Durga: Surveying the Sharodiya Specials in Bengal

Illustrating Durga: Surveying the Sharodiya Specials in Bengal

Puja Barshikis—the special annual editions released during Bengal’s Durga Puja—are a rich blend of literature, essays, art, and illustration. More than just magazines, they encapsulate cultural identity, festive nostalgia, and Bengal’s enduring intellectual tradition, serving as cherished literary companions across generations.

The origins of this tradition trace back to 1872, when Sulabh Samachar, a weekly newspaper founded and edited by Keshab Chunder Sen, published a special issue titled Chutir Sulabh in the month of Ashwin 1280 B.S. (1873). This pioneering effort sparked a trend soon embraced by other vernacular periodicals such as Sadhana, Bharatbarsha, and Bangabani. By the early twentieth century, Anandabazar Patrika joined the movement, further popularising the format.

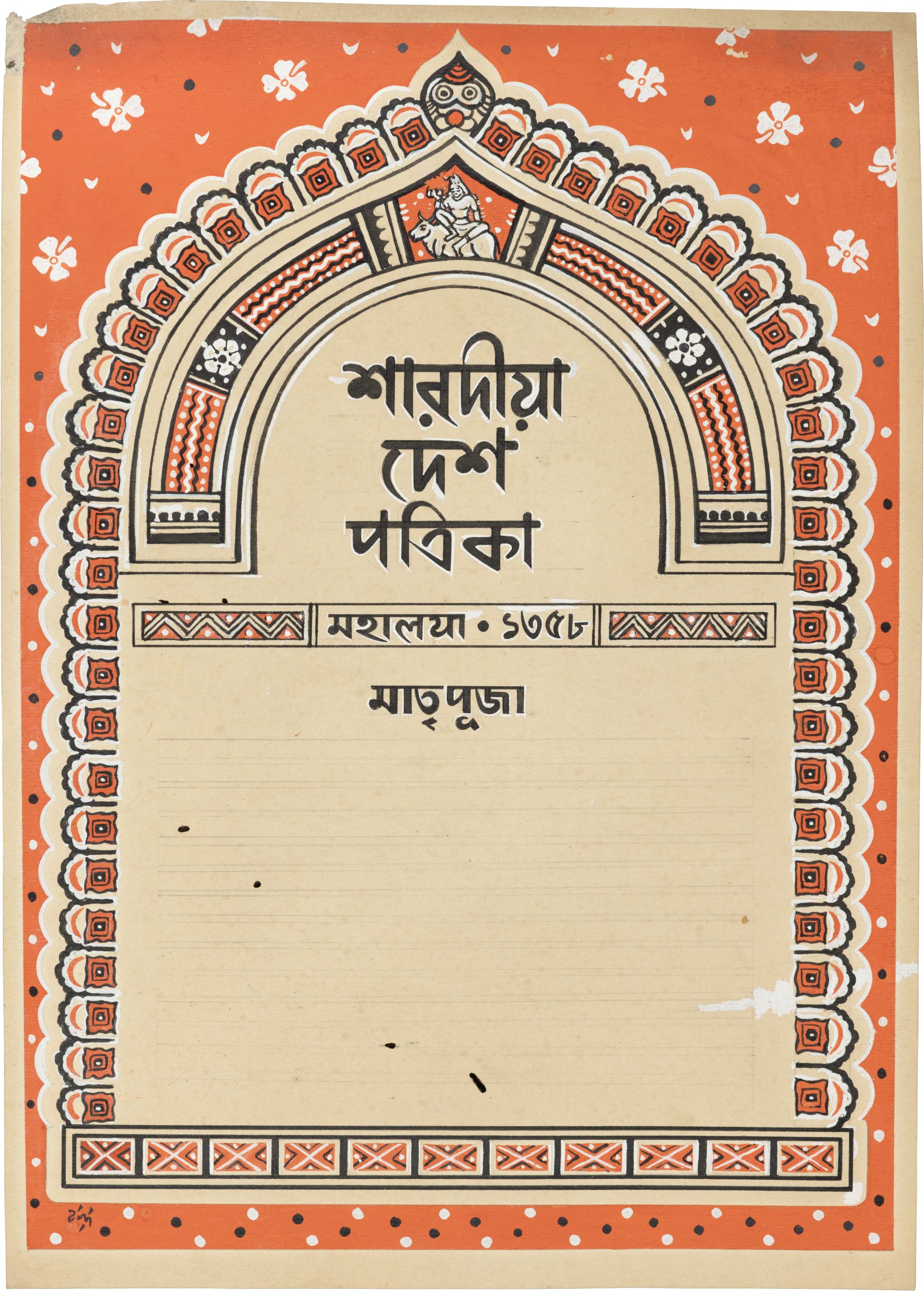

Over time, iconic publications like Anandamela, Sananda, Desh, Bartaman, and various pan-Indian Puja magazines institutionalized the tradition. These Barshikis evolved into significant cultural artifacts—repositories of short fiction, poetry, and essays—where literature, visual design, and artistic expression converged to create a unique festive experience year after year.

A Pujo Sankha without illustrations is almost unimaginable today. It’s easy to forget a time when books, magazines, and posters were our only portals to visual delight. Back then, illustrations weren’t just decorative—they were magical. Just as readers imagined scenes through words, an artist’s interpretation brought stories vividly to life, either complementing the reader’s imagination or offering entirely new perspectives. In an interview with Sandip Dasgupta, the renowned artist and illustrator Subrata Chowdhury reminisced about his childhood. Though no one in his family was an artist (his father served in the military), he grew up immersed in Puja Sankhas and Barshikis. While others were out pandal-hopping, he would spend hours poring over the illustrations, often returning to the accompanying stories to see if the visuals truly matched. This habit became a source of fascination and inspiration, eventually leading him to sketch in the margins of his school notebooks. For many like him, these illustrations were not just eye-catching—they were formative, nurturing the artists of the future.

Anandabazar Patrika launched its first Puja issue in 1922 as a modest two-page supplement, printed in distinctive red ink and distributed free with the daily newspaper. By 1926, this had expanded into a 54-page edition, sold for two annas—though notably, it still lacked illustrations. A pivotal transformation came in 1935 under the editorship of Satyendranath Majumdar. That year, the Puja number emerged as a substantial literary annual, priced at eight annas. It featured essays by prominent intellectuals such as Prafulla Chandra Ray, Jadunath Sarkar, Suniti Kumar Chatterjee, Vidushekhar Shastri, and Annada Shankar Ray. Also included were a piece on Bengali cinema by Narendra Dev, a blessing poem by Rabindranath Tagore, verses by Sajanikanta Das and Promothonath Bishi, and illustrations by the legendary Nandalal Bose. This thoughtful convergence of literature and visual art marked a turning point—firmly establishing the Anandabazar Patrika Puja Barshiki as a cultural institution in its own right.

While literature formed the backbone of the Puja Barshikis, the role of visual art was no less vital. Artists contributed significantly—not only by designing covers and producing illustrations, but also by creating a rich visual dialogue with the texts, thereby elevating the overall aesthetic and cultural experience. Archival materials strongly support this deep collaboration between writers and artists. Although the inaugural Anandabazar Patrika Puja Barshiki of 1933 appeared without any illustrations, visual art made its debut soon enough.

A 1943 letter from Nandalal Bose to Kanai Samanta further testifies to this connection:

'Meet Sagarmoy Ghosh of Anandabazar and take the manuscript of Anatomy, as he has a special need for it. While publishing it in Desh magazine, a few differences have appeared.'

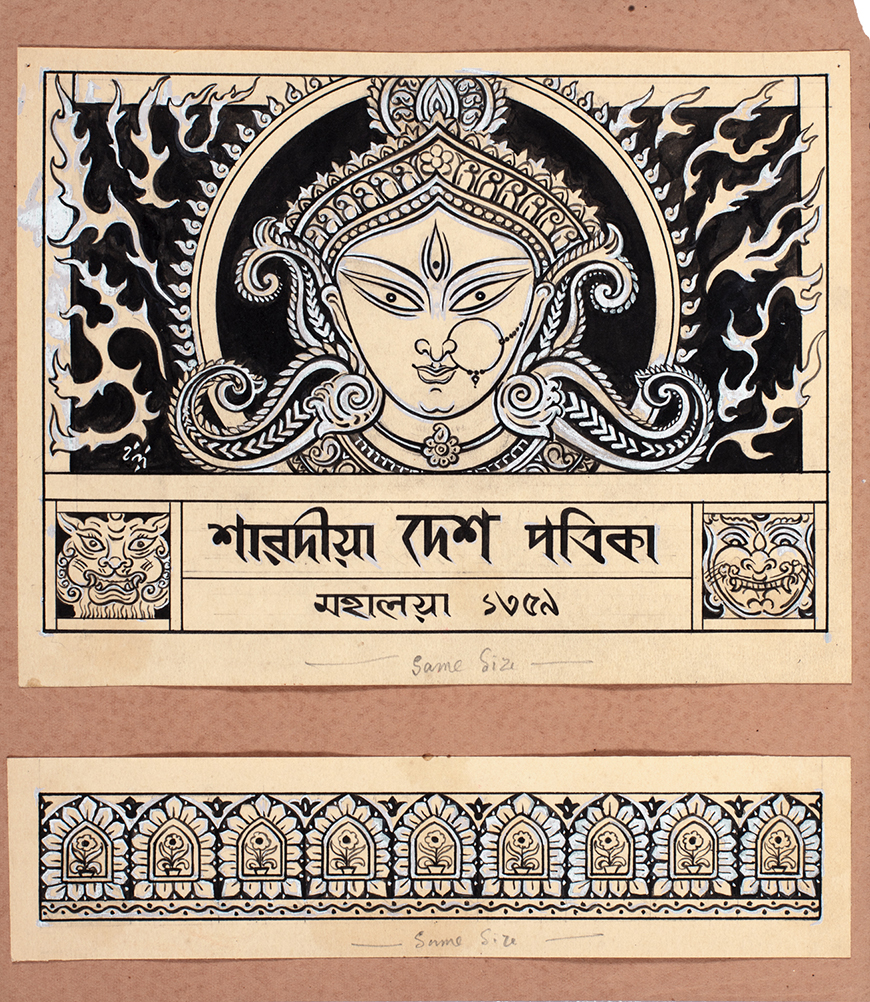

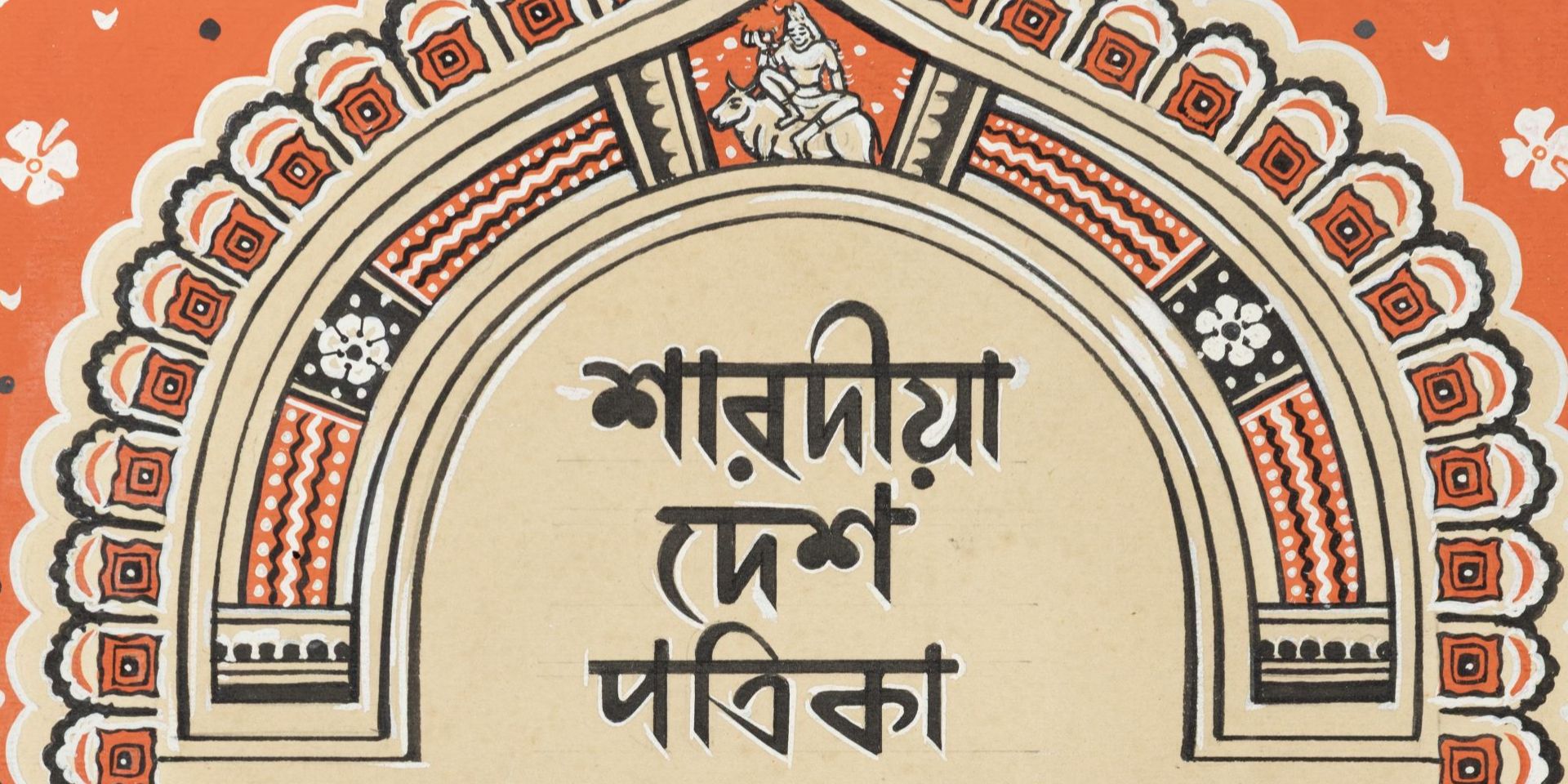

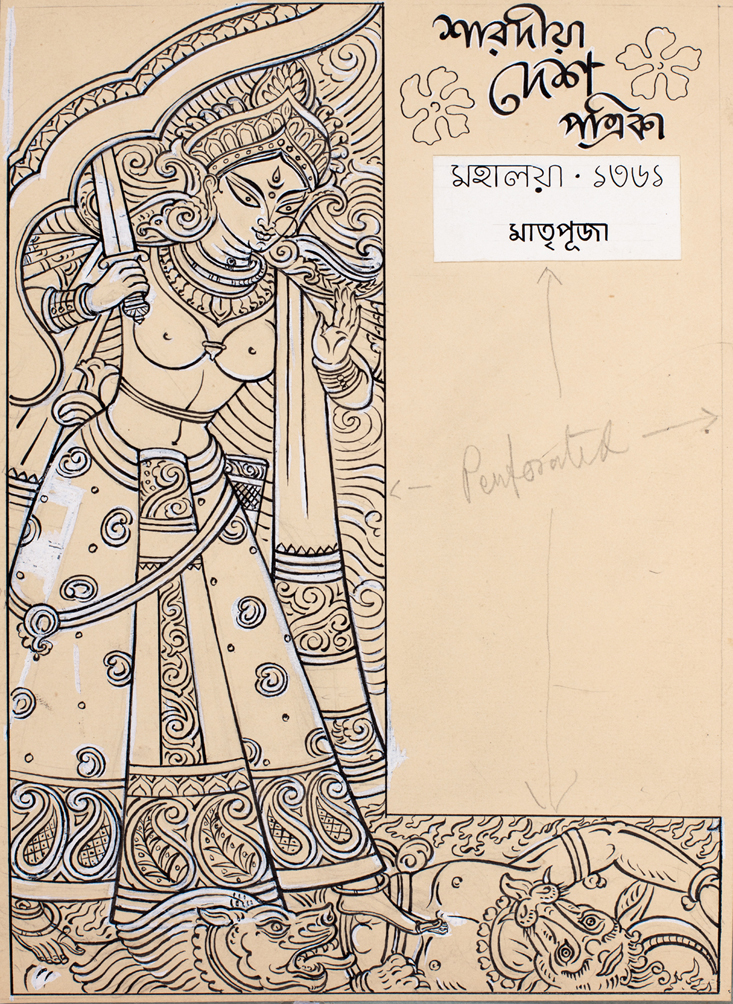

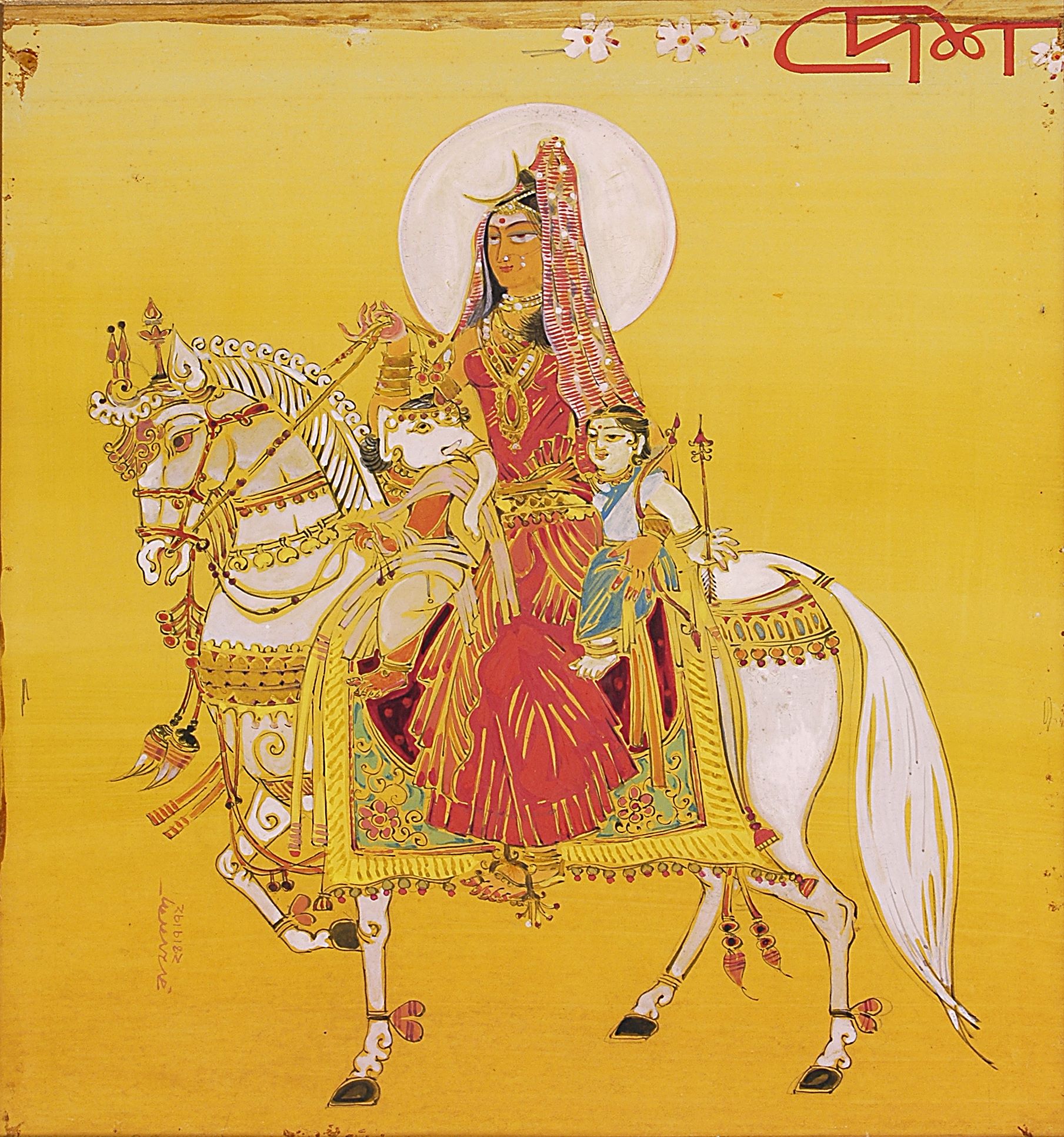

Another striking piece of evidence is a postcard drawing, likely sent by Bose to Samanta, bearing the handwritten Bengali inscription: “Kanai Samanta / Puja Sankha.” Such documents confirm Bose’s direct involvement with the Desh Puja Sankha, published by Anandabazar Patrika (now part of the ABP Group). Later records indicate that Bose also designed cover pages for several Puja issues.

Similarly, a postcard drawing by Gopal Chandra Ghose includes an inscription on the reverse: “Desh Puja / Gopal Chandra Ghose.” These collectively underscore the essential role that visual art played in the making of Barshikis, positioning them as a collaborative canvas for both literary and artistic expression.

As Rajlaxmi Basu noted in Anandabazar (8 October 2019):

'Even those who don’t buy books throughout the year often fall under the magical spell of the Puja issues and end up purchasing at least one magazine. And regular readers can often recognize an illustration by Bimal Das or Samir Sarkar without even looking at the signature.'

This observation highlights how profoundly illustration has shaped both the identity and reception of Puja Barshikis. From the Bengal School to contemporary times, artists like Indra Dugar, Nikhil Biswas, Ramananda Bandyopadhyay, Bikash Bhattacharya, Ganesh Haloi, and many others have lent their creative vision to these festive publications. Their contributions have ensured that the Barshiki endures not just as a literary tradition, but as a dynamic space where literature and visual art continue to nourish and elevate one another.

While the Barshikis cultivated an aesthetic and literary imagination, advertisements played a parallel role in shaping a vibrant popular visual culture. By the early 20th century, seasonal ads began appearing in local print media, promoting products such as “indigenous oils, silks, dhutis, saris, shoes, tea, sugar, and cigarettes”—often under culturally evocative names like Vidyasagar, Sri Durga, and Durbar.

By the mid-20th century, Puja pandals had transformed into vibrant community spaces, festooned with hoardings, banners, and hand-painted signboards advertising everything from sari boutiques and jewellery stores to sweet shops. These visuals often incorporated devotional imagery, blurring the boundaries between commerce and ritual. Around this time, major brands like HMV Music, Philips, and various costume companies began leveraging the festive season—placing ads across newspapers and hoardings, embedding themselves into the visual and cultural fabric of Puja celebrations.

The evolution of the Puja Barshiki and the rise of Puja advertising reveal that Durga Puja has always been more than just a religious celebration. The Barshikis created a lasting cultural archive—blending literature and illustration in ways that shaped the imaginations of generations of readers and artists. Advertising, on the other hand, transformed the festival into a powerful platform where commerce could align itself with emotion, ritual, and collective identity. Together, these practices highlight how Durga Puja has long functioned as a space where creativity and consumption intersect. Yet this rich history also brings pressing questions into focus today. In an era of mass-produced digital visuals and AI-generated imagery, what becomes of the singular artistic vision that once defined Barshiki illustrations? As corporate sponsorship and digital marketing increasingly shape the visual language of Puja, do these narratives meaningfully engage with the festival’s cultural core—or do they merely repackage it for broader consumer appeal? Moreover, with a significant portion of a state's annual marketing budget now directed toward the Puja celebrations, what are the implications of that economic investment? How does this commercial emphasis influence the ways in which memory, belonging, and identity are constructed and experienced through the festival?