Ideals under a shadow: Japanese aesthetics and Indian modernismAnkan Kazi May 01, 2024 Japan had defeated Russia in a war (1904-1905), leading to its rise as an imperial superpower in Asia. While Indian intellectuals like Rabindranath Tagore admired the aesthetic vitality of Japanese life, he remained critical of Japan’s aggressive imperialism and self-aggrandising nationalism, which would lead them to attack and occupy China, another major Asian power, in the late 1930s. However, with Japan’s victory over Russia, a wave of optimism washed over the colonised peoples of Asia, leading them to imagine a revival of their own national cultures. This confidence was manifested in the arts with figures like Abanindranath choosing to break from the rigid academicism that was taught in the colonial art schools of India, employing, instead the Japanese-inspired ‘wash’-technique. But what were some of the Japanese ideas that were influencing these artworks? We take a close look at two important texts and the potential they have in constructing a wider interpretation of Bengal art as a cosmopolitan event, whose effects reached far beyond Bengal. |

Nikhil Biswas

Untitled

Collection: DAG

|

The Ideals of the East Okakura Kakuzō (also known as Okakura Tenshin) was a Japanese scholar, art critic, and educator who lived from 1862 to 1913. He played a significant role in introducing Japanese culture to the West, as well as India, and promoting the concept of ‘Asia as one’ during a time when Japan was modernising and Westernising. Okakura Tenshin's The Ideals of the East is a seminal work that delves into the philosophical underpinnings and cultural essence of Eastern civilizations, particularly Japan and China, in contrast to the Western worldview. In his essay, Okakura emphasizes the holistic and spiritual nature of Eastern thought, contrasting it with the materialistic and individualistic tendencies of the West. He argues that while Western civilization focuses on progress, material wealth, and scientific advancement, Eastern ideals prioritize harmony, interconnectedness, and spiritual enlightenment. |

|

|

Nandalal Bose

Untitled

1948, Watercolour on card, 3.7 x 5.7 in.

Collection: DAG

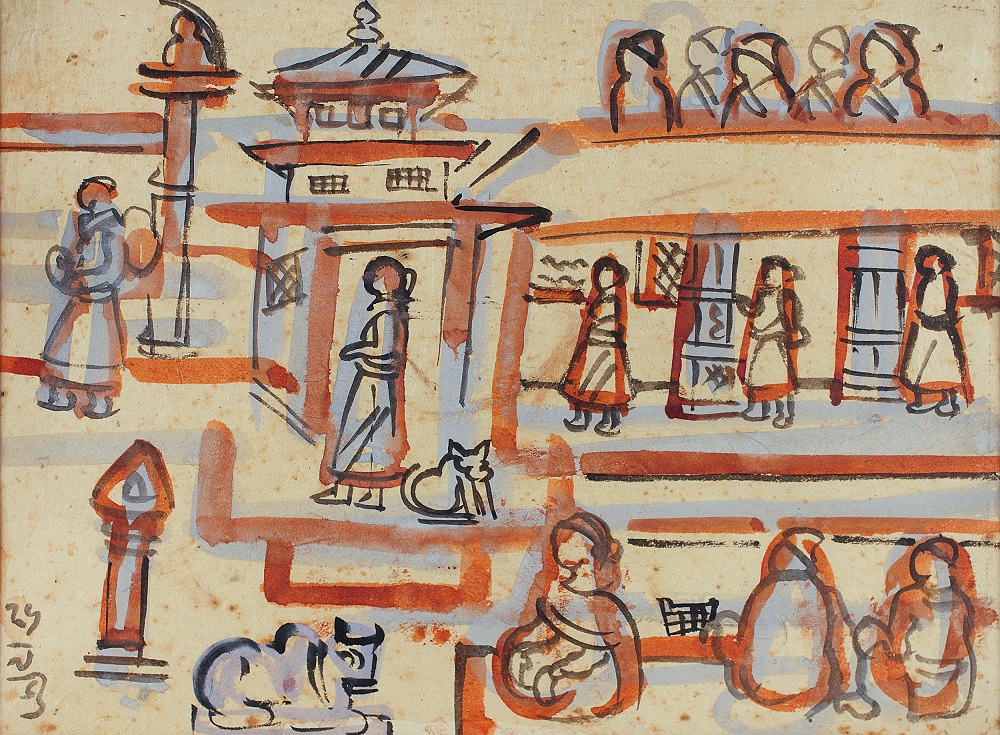

Benode Behari Mukherjee

Nepal

Tempera on Nepali paper pasted on mount board

Collection: DAG

Central to Okakura's thesis is the concept of 'cha-no-yu', or the Japanese tea ceremony, which he sees as a microcosm of Eastern philosophy. The tea ceremony embodies simplicity, humility, and aesthetic appreciation, reflecting a deeper understanding of the interconnectedness between humans, nature, and the divine. Through the ritual of preparing and consuming tea, individuals are encouraged to cultivate mindfulness and appreciation for the transient beauty of existence. One of Okakura's key arguments is the contrast between the Western emphasis on individualism and the Eastern emphasis on collective harmony. He criticizes the Western tendency to prioritize individual desires and ambitions over communal well-being, leading to social fragmentation and alienation. In contrast, Eastern societies, according to Okakura, value communal bonds and mutual respect, fostering a sense of interconnectedness that transcends individual egoism. |

|

Furthermore, Okakura highlights the importance of aesthetics in Eastern thought, particularly in the realms of art and literature. He argues that Eastern aesthetics are rooted in a deep reverence for nature and a keen awareness of the impermanence of life. Unlike the Western pursuit of immutable beauty and perfection, Eastern aesthetics embrace imperfection and transience, finding beauty in the ephemeral and the incomplete. Such ideas underpin the work of many Indian artists who trained at Santiniketan, especially Nandalal Bose, who even chose to work with ephemeral media like postcards on which he made lots of sketches, and with partial shapes or forms on paper which he attempted to elevate with his sensibility of beauty. |

|

|

Asit Haldar

Untitled

Water colour on handmade paper

Collection: DAG

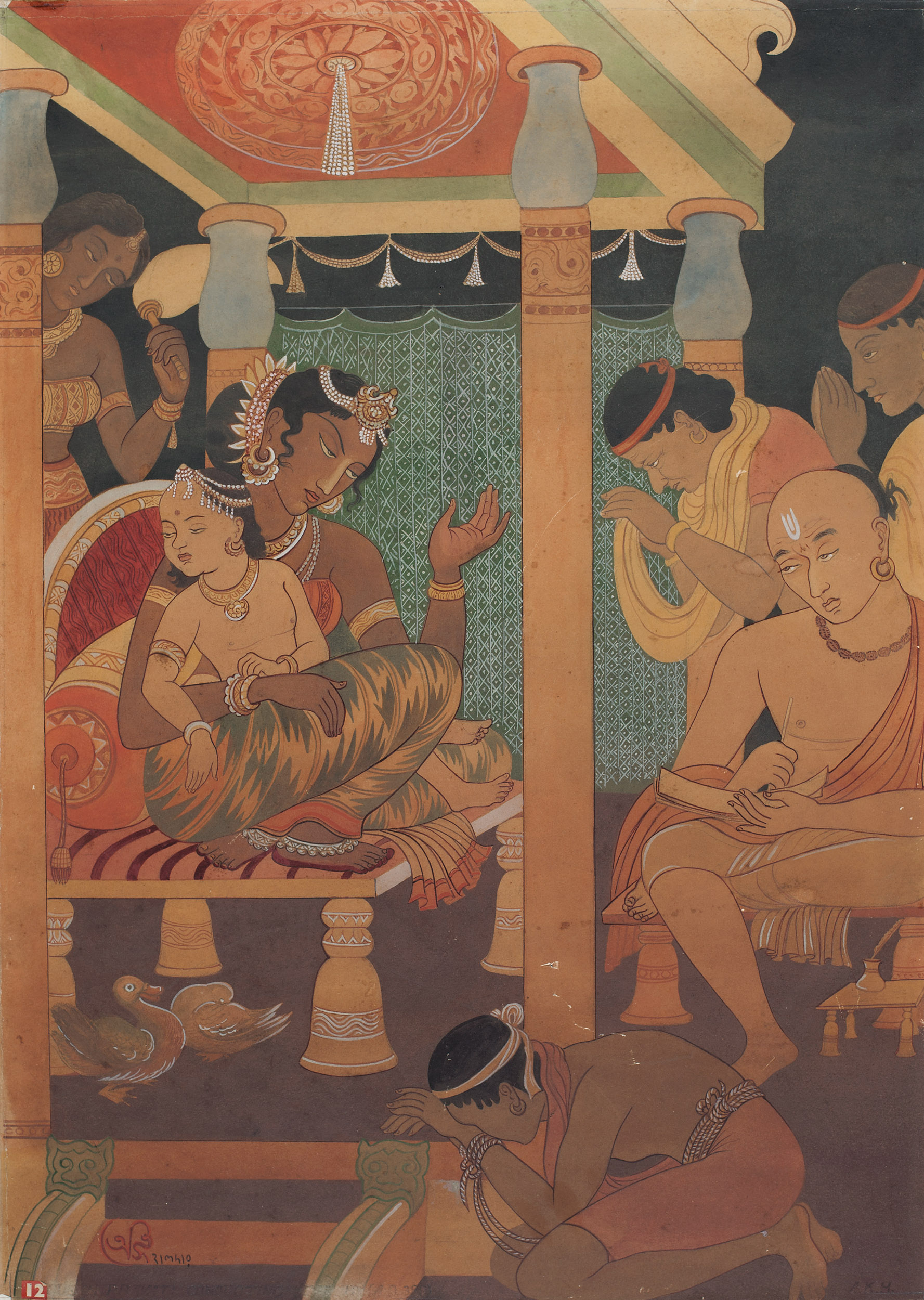

Katsuta Shokin

Untitled (Rama's Parting)

c. 1906-07, Gouache, watercolour and gold pigment on silk pasted on board, 40.2 x 16.2 in.

Collection: DAG

Okakura’s influence on the Bengal School of Art, particularly through his ideas on aesthetics and cultural identity, was profound. The Bengal School of Art emerged in the early twentieth century as a reaction against the dominance of Western academic art forms in India. Led by artists like Abanindranath Tagore, Nandalal Bose, and E. B. Havell, the Bengal School sought to revive traditional Indian artistic techniques and themes while incorporating elements of Japanese and Chinese art, largely inspired by Okakura's writings. The Ideals of the East resonated deeply with such artists, who were grappling with questions of cultural identity and artistic expression in the face of colonialism and cultural assimilation. Okakura's emphasis on the interconnectedness between art, spirituality, and nature struck a chord with Bengali artists, who saw parallels between his ideas and the ethos of Indian philosophical traditions such as Vedanta and Buddhism. |

|

Furthermore, Okakura's advocacy for the preservation of traditional arts and crafts resonated with the Bengal School's efforts to revive indigenous artistic techniques such as the use of natural dyes, handcrafted paper, and traditional brushwork. |

|

|

Nandalal Bose

Untitled (Sati)

Graphite on paper

Collection: DAG

Abanindranath Tagore

Bharat Mata

Chromolithograph on paper

Collection: DAG

Critically analysing Okakura's ideas, it is important to consider the historical context in which he wrote. The Ideals of the East was published in 1904, during a period of rapid modernization and globalization in Japan. Okakura's defence of traditional Eastern values can be seen as a response to the perceived threat of Western cultural hegemony and the erosion of Japanese cultural identity. However, Okakura's romanticization of Eastern ideals and his dichotomous portrayal of East versus West have been subject to criticism. Some scholars argue that his characterization oversimplifies the complexities of both Eastern and Western cultures, neglecting the diversity of thought and practice within each civilization. Additionally, Okakura's idealisation of Eastern spirituality and communal harmony has been seen as ahistorical, ignoring the conflicts and inequalities that have plagued Eastern societies throughout history. A work such as Nandalal Bose’s depiction of Sati, for instance, carries overtones of this spiritual romanticisation of harmful social practices that Indian reformers themselves were trying to critique and outlaw. |

|

The use of Japanese stamps, or ‘chops’, in Bengal School paintings was likely influenced by the Japanese woodblock printing tradition. These stamps were used as signatures by artists to authenticate their work. Incorporating Japanese stamps into their paintings may have been a way for Bengal School artists to pay homage to Japanese art traditions and signify their affiliation with broader Asian artistic movements. Additionally, it could have been a stylistic choice to add visual interest and cultural depth to their artworks, giving their own signatured selves a fantasy of cross-cultural identity-formation. |

|

|

|

In Praise of Shadows In Praise of Shadows is one of Jun'ichirō Tanizaki's most famous essays. He wrote it in 1933. Tanizaki was a Japanese novelist and essayist, renowned for his exploration of cultural themes, psychological depth, and intricate storytelling. He lived from 1886 to 1965, witnessing a similar transition to modernity in his country as artists from South Asia did. |

|

|

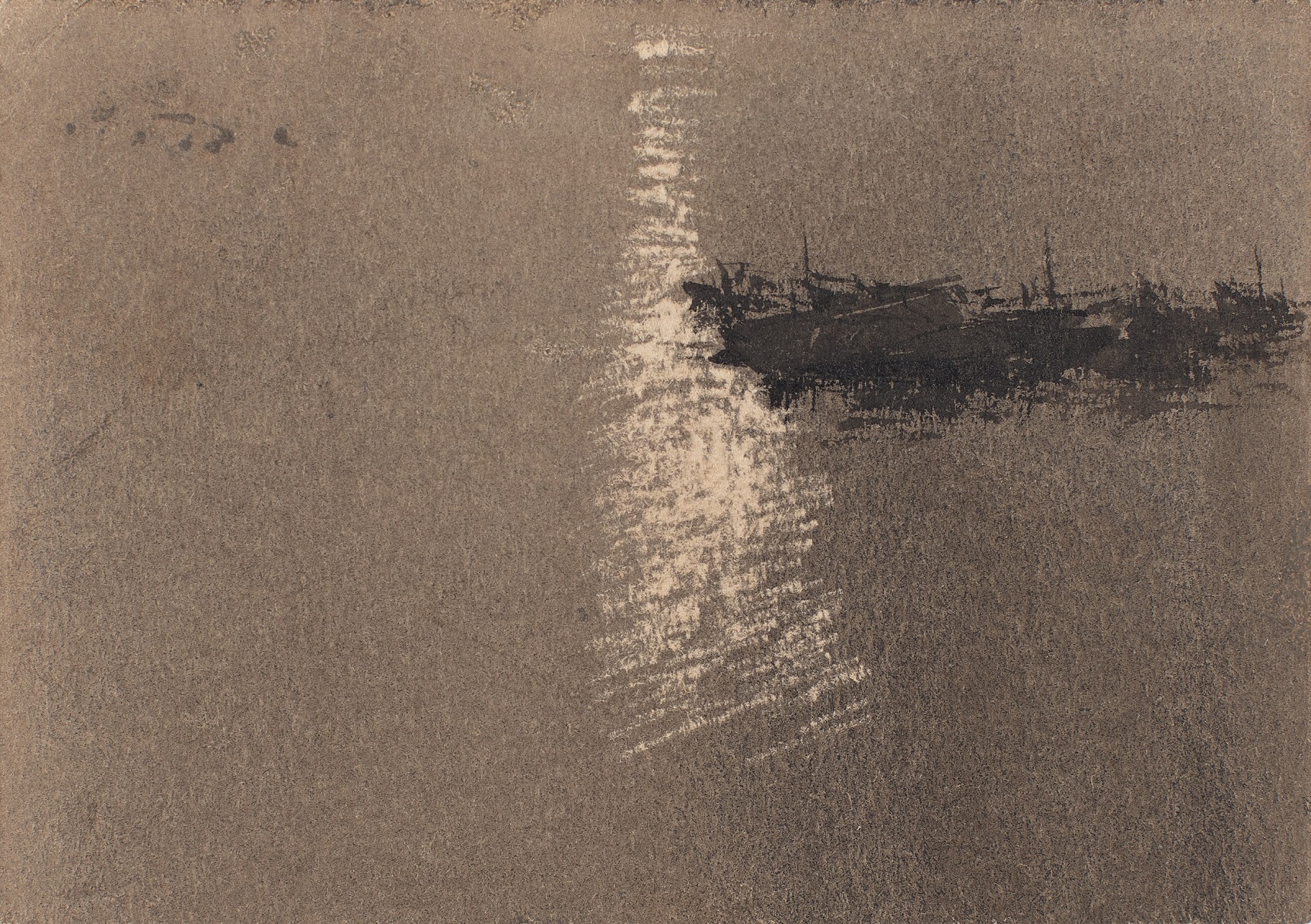

Abanindranath Tagore

Untitled (Shadow by River)

Water colour on postcard

Collection: DAG

The book-length essay offers a captivating exploration of the aesthetic and cultural values embedded within traditional Japanese architecture and design. Through eloquent prose and introspective musings, Tanizaki delves into the nuances of light, shadow, and the subtleties of Japanese craftsmanship, contrasting them with the harsh glare and starkness of modernity. In doing so, he presents a critical reflection on the impact of Westernisation on Japanese culture and identity. One of the central themes in Tanizaki's essay is the appreciation of shadows. He argues that shadows add depth and mystery to the environment, creating a sense of tranquillity and intimacy. Tanizaki writes, ‘We find beauty not in the thing itself but in the patterns of shadows, the light and the darkness, that one thing against another create'. Here, he suggests that beauty is not inherent in objects but is instead a product of the interplay between light and shadow. |

Gaganendranath Tagore

Untitled

Water colour and ink on pape

Collection: DAG

Tanizaki contrasts the aesthetic sensibilities of Japan with those of the West, particularly in regard to architecture and interior design. He laments the loss of traditional Japanese architecture, with its emphasis on natural materials and subtle textures, in favour of modern, Western-style buildings that prioritize functionality and efficiency. Tanizaki expresses his nostalgia for the dimly lit interiors of traditional Japanese houses, where shadows dance on paper screens and wooden beams. He writes, ‘In a Western-style room, more or less furnished in modern taste, the host and guest alike feel a certain uneasiness’. Here, he suggests that the harsh lighting and lack of shadows in Western interiors disrupt the sense of harmony and intimacy that is characteristic of Japanese spaces. |

|

Tanizaki reflects on the cultural significance of darkness in Japanese society. He argues that darkness is not something to be feared or avoided but rather embraced as an essential aspect of life. Tanizaki writes, ‘Were it not for shadows, there would be no beauty’. Here, he implies that darkness is necessary for the appreciation of light and beauty, echoing traditional Japanese philosophies such as Zen Buddhism. |

|

|

Gaganendranath Tagore

Untitled

Water colour on paper

Collection: DAG

S. N. Kar

Untitled

5.5 X 3.5 in.

Collection: DAG

As A. C. Grayling put it, ‘In his delightful essay on Japanese taste… Tanizaki selects for praise all things delicate and nuanced, everything softened by shadows and the patina of age, anything understated and natural—as for example the patterns of grain in old wood, the sound of rain dripping from eaves and leaves, or washing over the footing of a stone lantern in a garden, and refreshing the moss that grows about it—and by doing so he suggests an attitude of appreciation and mindfulness, especially mindfulness of beauty, as central to life lived well.’ |

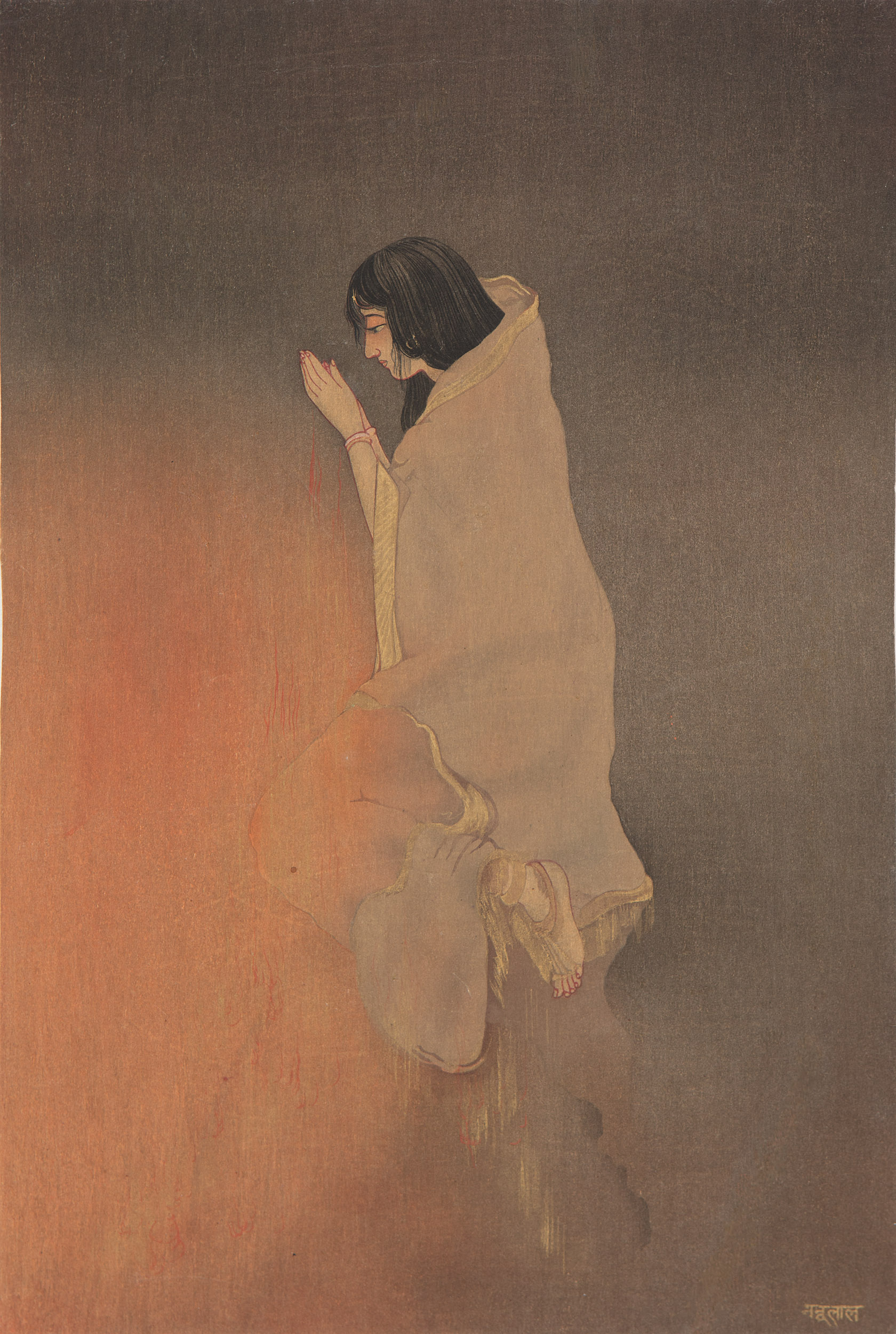

Gaganendranath Tagore

Swapanacharani

Ink on paper pasted on rice paper, 5.5 x 2.5 in.

Collection: DAG

While Tanizaki's essay primarily explores the aesthetic qualities of traditional Japanese architecture and design, Okakura's book offers a broader examination of Eastern philosophy and culture, encompassing not only Japan but also China and India. Okakura's work seeks to uncover the underlying spiritual and philosophical principles that unite Eastern civilizations, whereas Tanizaki's focus is more narrowly on the aesthetics of Japan. In spite of this, it is intriguing to note how artists like Gaganendranath Tagore explored the use of umbral zones and forms in his pictures, investing them with connotations of narrative, mystery and wonder, rather than danger or savagery. Sensitive towards the manifestation of beauty in everyday life and practice, and committed to the forging of a nationalist aesthetic under the shadow of Swadeshi, these works point to a similar aesthetic agenda in Tagore’s mind as well, who adopted many influences from Japanese art in his own practice. |

|

Moreover, these concepts do not only address ideals and forms, but also materials for making art. As a critic of a new translation of the book noted, ‘Tanizaki… samples a number of instances where the use and perception of light differs from the West, noting that, where Western paper reflects light, traditional Japanese paper absorbs it.’ Tanizaki's In Praise of Shadows and Okakura's The Ideals of the East share some common themes and concerns, but they approach the subject of Japanese aesthetics and culture from different angles. Despite these differences, both works contribute valuable insights into the enduring appeal of Japanese culture and its unique aesthetic sensibilities. And due to its moment of creative encounter with Indian modern art, its tendencies to celebrate traditional practices like the tea ceremony, calligraphy or flower arranging were variously adopted by Indian artists, especially those in Santiniketan, as they too tried to devote their attention to art forms like the alpona or mural-making. Above all, these texts allowed Indian artists and intellectuals to rediscover a sense of pride in their own culture, which was a crucial step in the larger process of winning back the political right for self-determination. |

|

|