Hybrid Visions: The Phenomenon of 'Company' Painting in India

Hybrid Visions: The Phenomenon of 'Company' Painting in India

Hybrid Visions: The Phenomenon of 'Company' Painting in India

Malabar or Madras Artist (Company School), Wild Jackfruit (Artocarpus hirsutus) (detail), c. 1807, Watercolour on paper. Collection: DAG

Company style painting, also known as Kampani Kalam, emerged in the late eighteenth century during the British East India Company's expansion in India. This hybrid art form combined traditional Indian styles, particularly Mughal and Rajput miniature painting, with European techniques like linear perspective, chiaroscuro, and illusionism.

The result was a unique fusion that reflected the cultural interactions between Indian artists and their European patrons. As the curator and art historian Mildred Archer put it, ‘This painting was mainly a product of the British connection and, despite many local differences of manner, it illustrated a single phenomenon—an attempt by Indian artists to adjust their styles to British needs and to paint subjects of British appeal.’

|

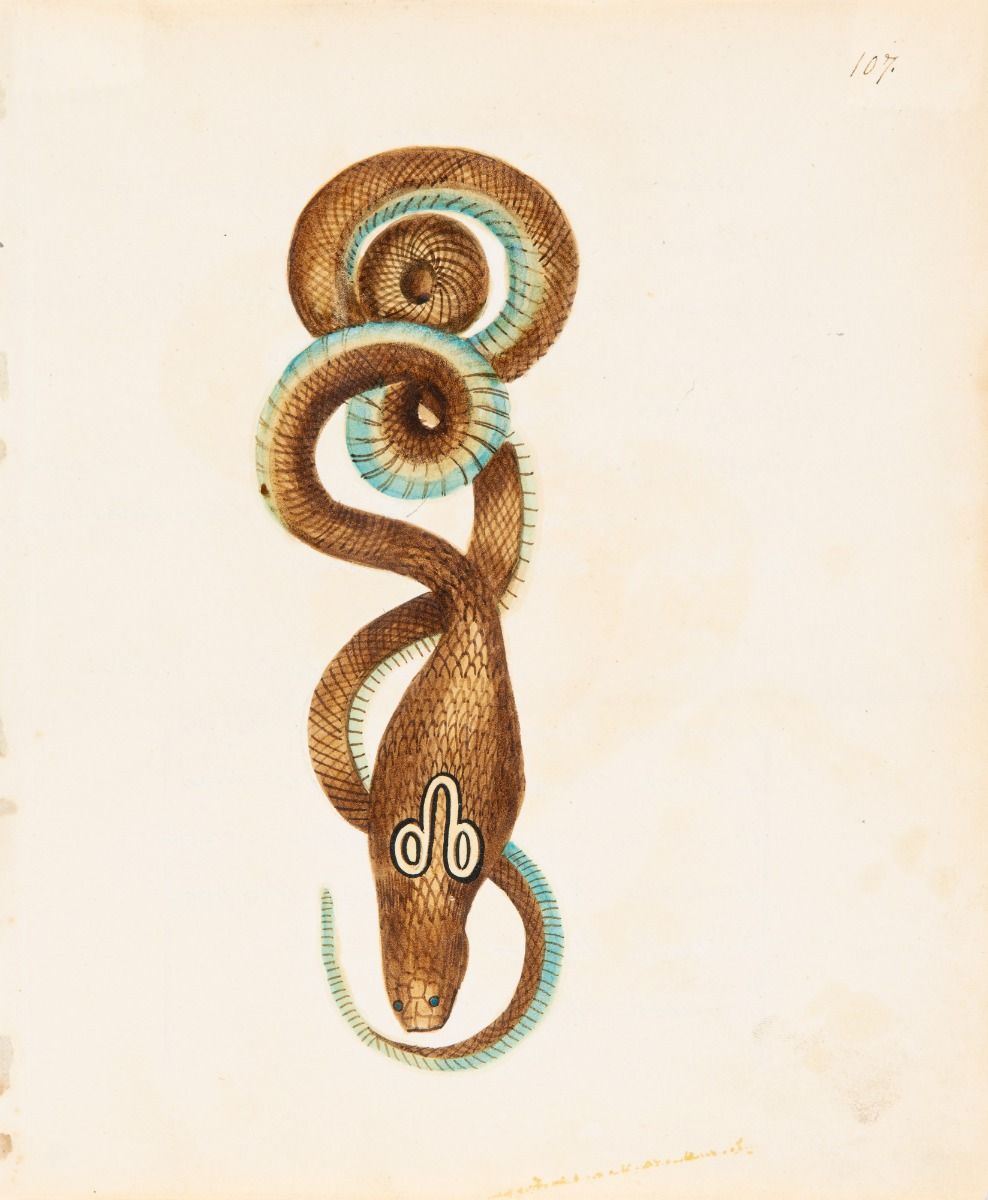

Unidentified Artist (Company School), Indian Binocellete Cobra (Naja naja), c. 1820, Watercolour on paper. Collection: DAG |

How did the style come about?

The decline of Mughal patronage after the mid-eighteenth century, coupled with the British East India Company's growing influence, led many Indian artists to seek new avenues of employment. These artists began working for European officials, creating paintings that documented India's people, landscapes, architecture, flora, and fauna. Archer notes that these works were often commissioned to serve as ethnographic records or personal souvenirs for British officers and their families.

|

Malabar or Madras Artist (Company School), Wild Jackfruit (Artocarpus hirsutus), c. 1807, Watercolour on paper. Collection: DAG |

The term ‘Company painting’ gained prominence after Archer's publication Company Paintings: Indian Paintings of the British Period. However, its roots trace back to earlier efforts by Archer and her husband William Archer in the 1930s. They were introduced to this genre through Patna's regional school of painting.

Besides serving as a record of new cultural encounters, Company paintings illustrate the rising value of pictures from the East, back in the metropolitan centres of Europe and allow us to imagine European encounters with the Orient as an aesthetic event, as much as a socio-political one, as technologies of vision shaped narratives of engagement with an exotic Other. Archer quotes Lady Nugent to show how she noticed ‘copper vessels, crockery, rice, sugar, gods and goddesses, knives, muslins, silks... were all displayed together - all sorts of coloured turbans and dresses, and all sorts of coloured people — the crowd immense — the sacred Brahmin bull walking about and mixing with the multitude’, almost as soon as she was off the boat, suggesting that the style sought to capture the varied impressions the colony hastened to make upon a traveller.

Characteristics and Techniques

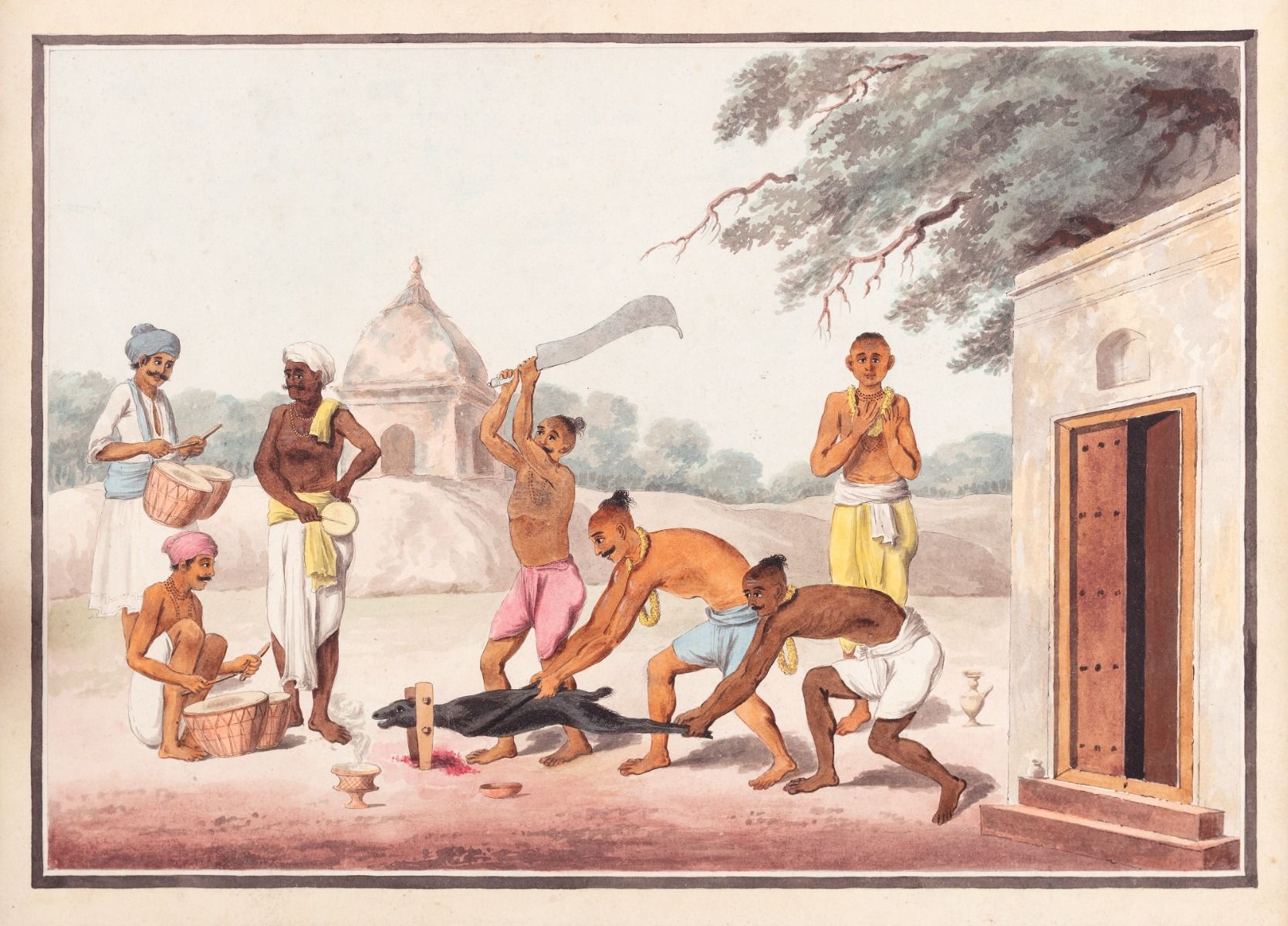

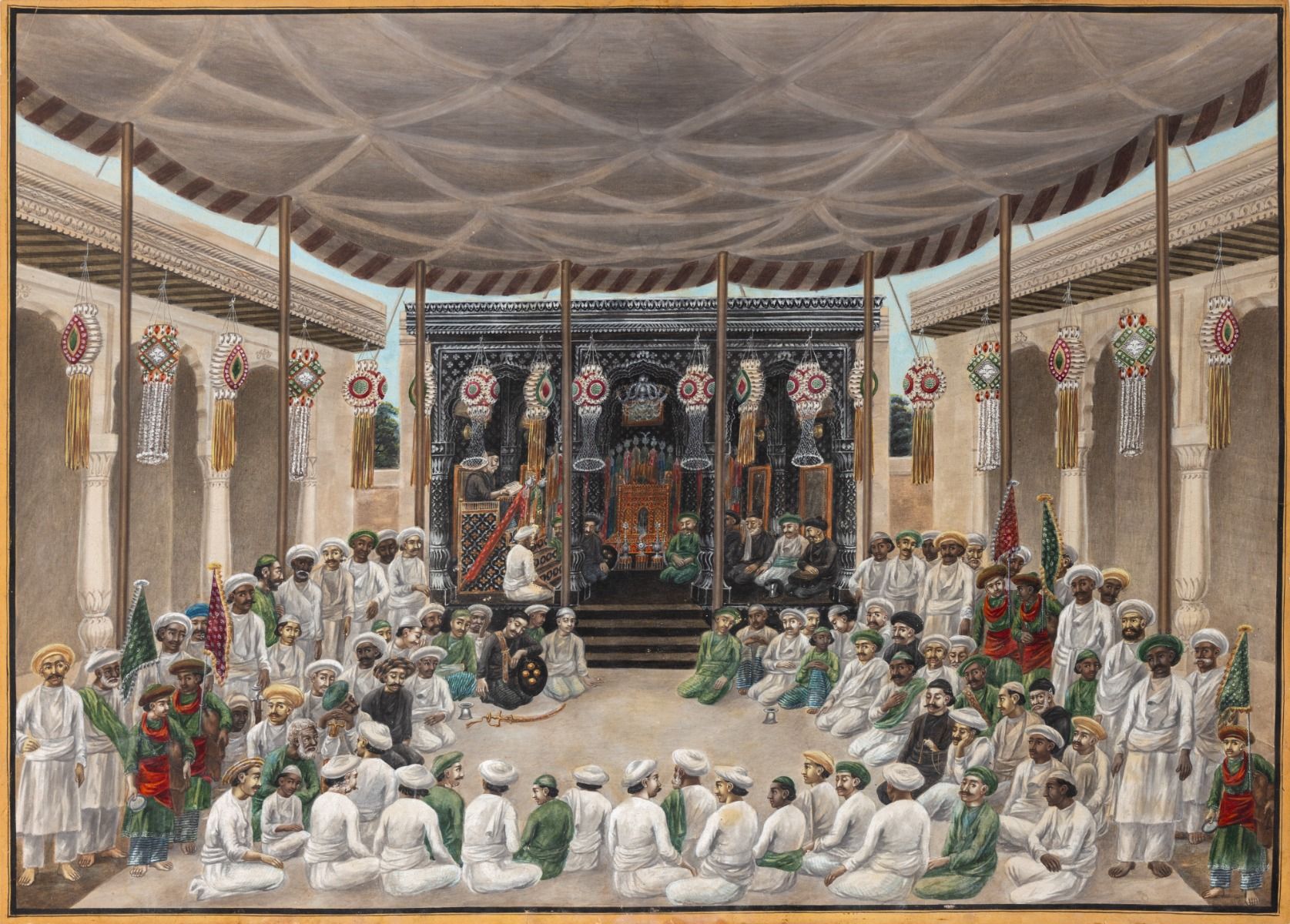

Company paintings were typically rendered in watercolours on paper or ivory, diverging from the traditional gouache used in Indian miniatures. They adopted Western techniques like tonal shading and perspective to create depth while retaining Indian elements such as intricate detailing and vibrant colours. Common themes included portraits of local figures, including artisans and common folk, depictions of festivals, trades, and caste-specific costumes—Archer suggests that the work of travelling artists like F. B. Solvyns was especially useful as a precursor for these representations; natural history illustrations of plants and animals, and architectural studies presented in a precise, almost draft-like style.

Murshidabad Artist (Company School), Fete des Hindous appellée Kales Pojas [Hindu Festival called Kali Puja], Watercolour on paper pasted on paper, early 19th century. Collection: DAG

The works often reflected the interests of their patrons. For instance, portfolios of botanical or zoological subjects catered to British tastes for scientific documentation, while depictions of daily life and Indian and British architecture offered picturesque views of India. Paintings also depicted estates, carriages, horses, and other possessions amassed by Company officials. Such works highlighted the material culture of colonial life.

Some of the most influential artists in the Company painting school include Sewak Ram, who was based in Patna and collected by governors and administrators, and was renowned for his large-scale depictions of festivals and ceremonies; and Ghulam Ali Khan, a prominent artist from Delhi, who worked extensively on commissions such as the Fraser Album, which featured over 90 paintings and drawings from 1815 to 1819. He is noted for his scenes of village life and portraits of Mughal emperors and their courts.

Company painting flourished in key centres of British influence such as Murshidabad, Patna, Delhi, Lucknow, Kolkata (Calcutta), Thanjavur (Tanjore), and Madras. Each region developed its own stylistic nuances. For instance, Patna specialized in depictions of local tradespeople, while Murshidabad retained Mughal influences in its portraiture.

Sewak Ram, Prayers and Recitations at the Muharram Festival, c. 1820–30, Opaque watercolour on paper. Collection: DAG

While many Company paintings were commissioned by British officials like William Fraser and James Skinner, Indian patrons also played a role. Even the work of popular travelling artists like Solvyns, the Daniells and William Hodges were often coloured or engraved by unknown Indian artists, helping them learn the methods of this new artistic style.

The popularity of Company paintings waned by the mid-nineteenth century, or one could suggest that it began to feed several new tendencies in Indian art practice as well, from the popular art of the bazaars, like the Kalighat style, or the academic styles that were beginning to be taught in colonial art schools. The latter could be seen as a direct response to the grudging admiration some British travellers and residents had about Indian art-making. The traveller Maria Graham would write, ‘…On landing, I was struck with the general appearance of grandeur in all the buildings; not that any of them are according to the strict rules of art, but groups of columns, porticoes, domes and fine gateways, interspersed with trees, and the broad river crowded with shipping, made the whole picture magnificent.’ The disciplining eye, which could follow the ‘strict rules of art’ were henceforth cultivated formally in the art schools, leading Indian artists to master the technical challenges that may have affected early Company school painters. However, their historical significance endures. Major collections are housed in institutions like the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and the British Library.

Sita Ram, A View of the Dargah of Sheikh Salim Chishti, Fatehpur Sikri, 1815–25, Watercolour on paper. Collection: DAG

Company style paintings represent a fascinating confluence of Indian and European artistic traditions during a transformative period in India's history. They not only document colonial India's visual culture but also highlight the adaptability and resilience of Indian artists under changing socio-political circumstances.