Histories in the Making: Photographing Indian Monuments, 1855–1920

Histories in the Making: Photographing Indian Monuments, 1855–1920

Histories in the Making: Photographing Indian Monuments, 1855–1920

|

Histories in the Making: Photographing Indian Monuments, 1855–1920 Dr. Bhau Daji Lad Museum Mumbai, 2 May - 17 August 2025 Curated by Sudeshna Guha

Thomas Biggs Plate LXXII. Iwullee, East Front of the Temple (Durga Temple, Aihole, Bijapur) Silver albumen print 1855 11.2 x 15.5 in. / 28.4 x 39.4 cm. Collection: DAG |

|

|

|

L. N. Taskar Untitled (Maharashtra Temple Scene) Oil on canvas Collection: DAG |

|

EARLY ENCOUNTERS

|

|

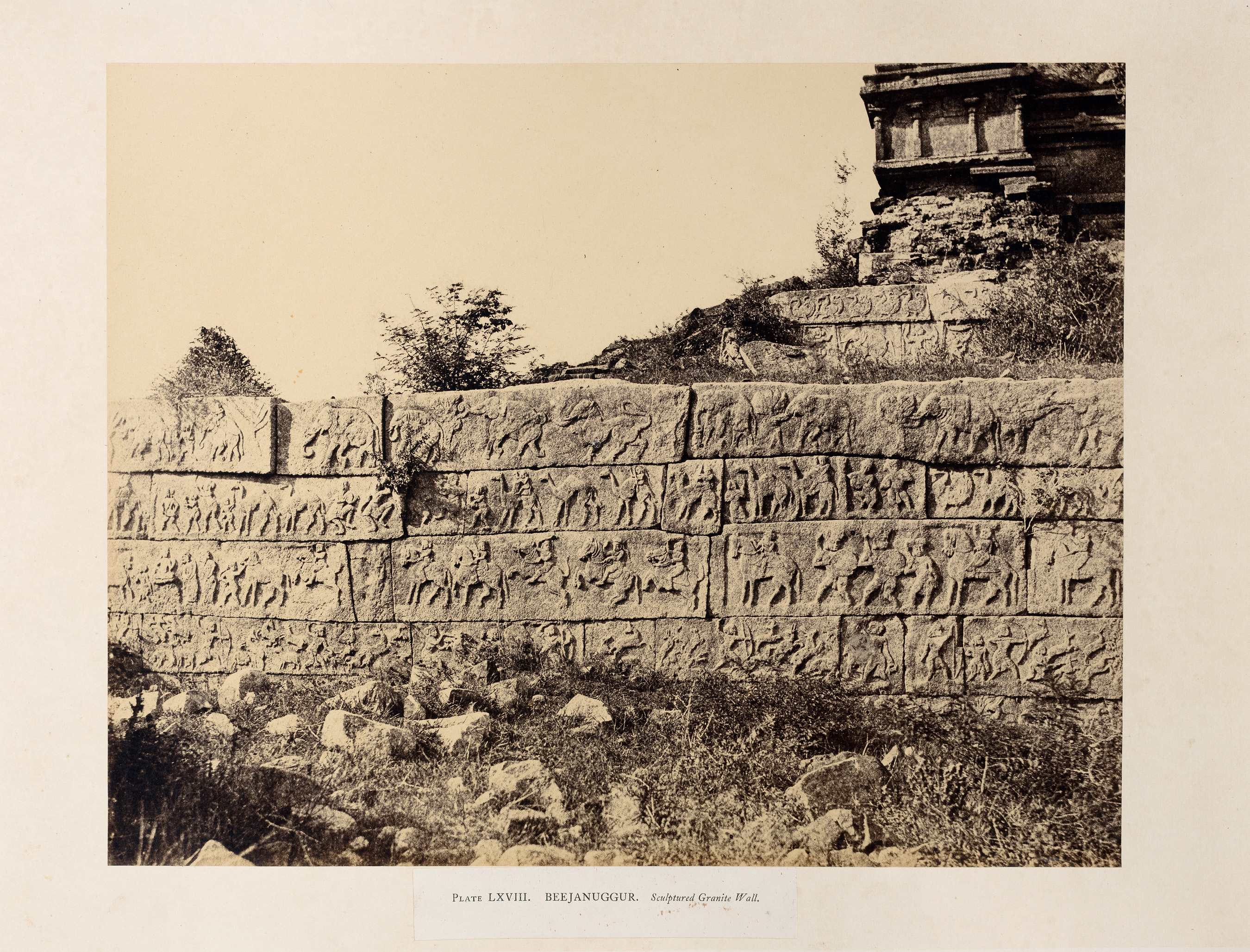

Andrew Charles Brisbane Neill Plate LXVIII. Beejanuggur, Sculptured Granite Wall (Hampi) Silver albumen print, 1856 10.5 x 13.5 in. / 26.6 x 34.2 cm.

|

William Henry Pigou

Mysore, Idol car at the temple of Chamondee (Chamundi Temple)

Silver albumen print, 1856

11.0 x 15.0 in. / 27.9 x 38.1 cm.

Collection: DAG

Thomas Biggs

Plate LXXII. Iwullee, East Front of the Temple (Durga Temple, Aihole, Bijapur)

Silver albumen print, 1855

11.2 x 15.5 in. / 28.4 x 39.4 cm.

Collection: DAG

Andrew Charles Brisbane Neill

Plate LXVIII. Beejanuggur, Sculptured Granite Wall (Hampi)

Silver albumen print, 1856

10.5 x 13.5 in. / 26.6 x 34.2 cm.

Collection: DAG

William Johnson and William Henderson

Caves of Elephanta – 7. From the Water Cave

Silver albumen print, 1855–62

7.5 x 9.5 in. / 19.0 x 24.1 cm.

Collection: DAG

John Murray

Khas Mahal, Agra Fort

Waxed paper negative, c. 1858–62

15.0 x 18.0 in. / 38.1 x 45.7 cm.

Collection: DAG

|

|

VISUAL INSCRIPTIONS

|

|

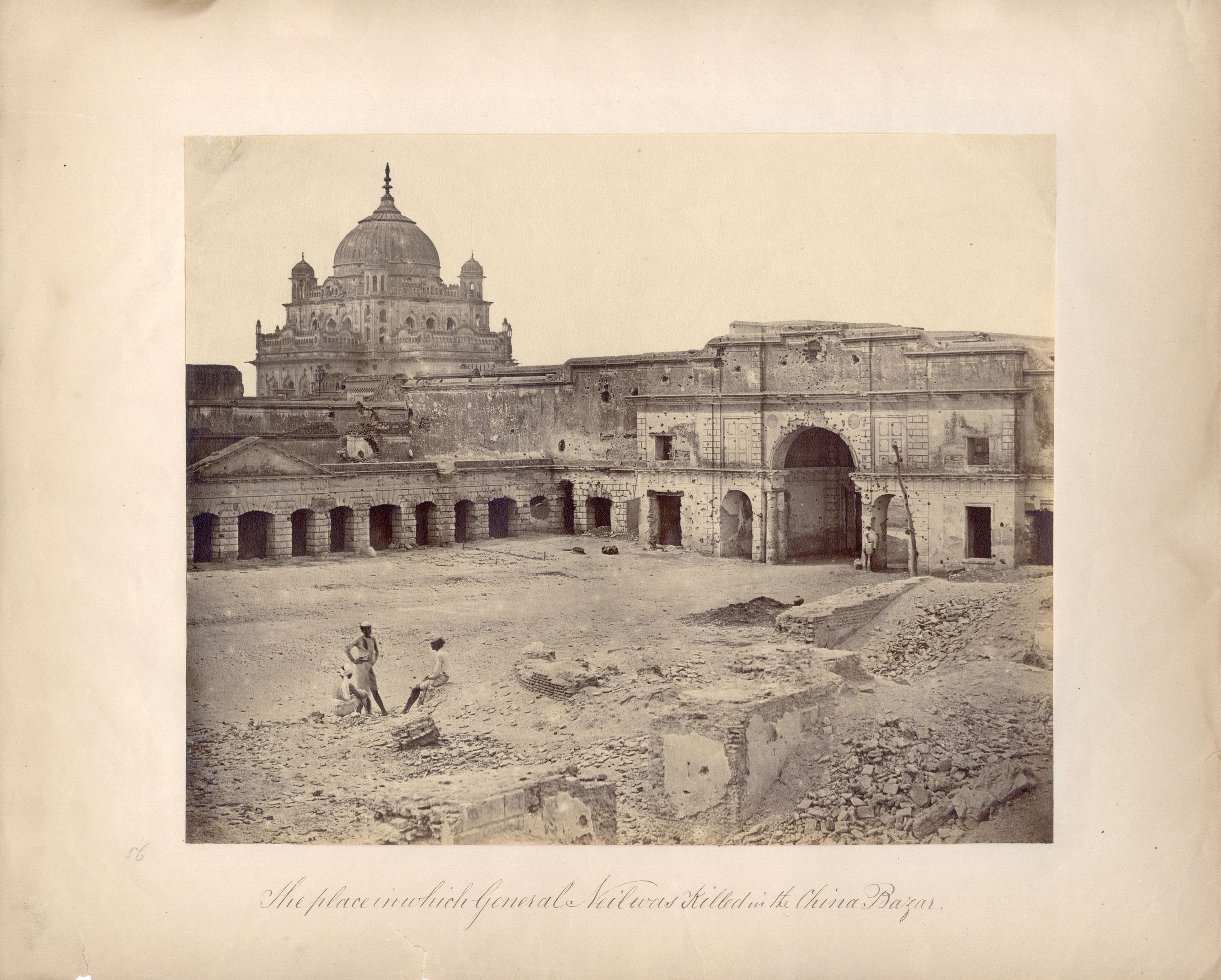

Felice Beato The Place in which General Neil was killed in the China Bazar (Lucknow) Silver albumen print, 1858 8.7 x 10.7 in. / 22.0 x 27.1 cm.

|

Felice Beato

The Place in which General Neil was killed in the China Bazar (Lucknow)

Silver albumen print, 1858

8.7 x 10.7 in. / 22.0 x 27.1 cm.

Collection: Sir J. J. School of Art

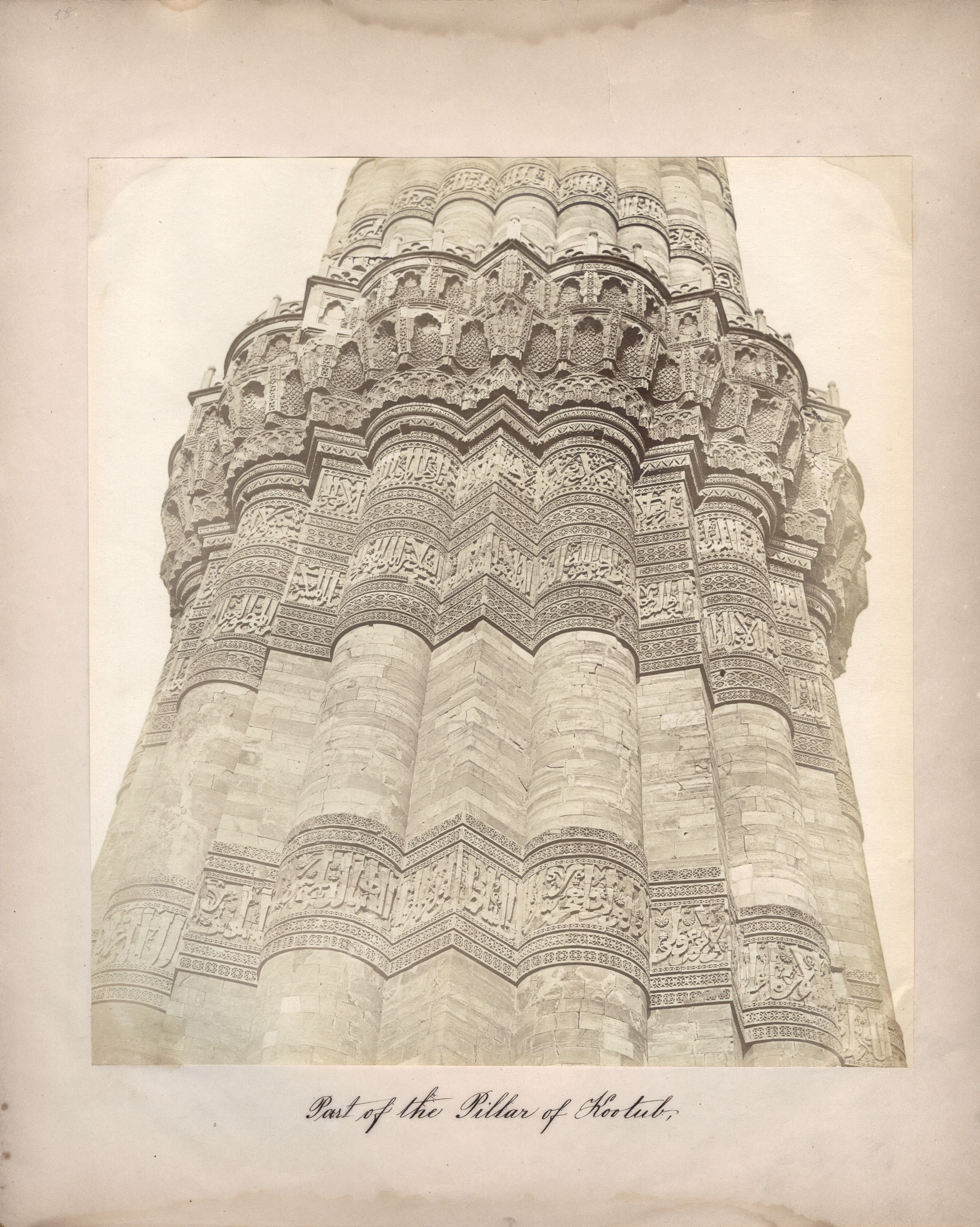

Felice Beato

Part of the Pillar of Kootub (Qutub Minar, Delhi)

Silver albumen print, 1858

11.0 x 10.2 in. / 27.9 x 25.9 cm.

Collection: DAG

Linnaeus Tripe

The Great Pagoda, View of the Sacred Tank in the Great Pagoda (Minakshi Sundareshvara Temple, Madurai)

Silver albumen print, 1858

10.2 x 15.0 in. / 25.9 x 38.1 cm.

Collection: DAG

Linnaeus Tripe

The Great Pagoda, The Pagoda Jewels (Minakshi Sundareshvara Temple, Madurai)

Silver albumen print, 1858

8.5 x 11.7 in. / 21.5 x 29.7 cm.

Collection: DAG

|

|

FIELD PHOTOGRAPHY

|

|

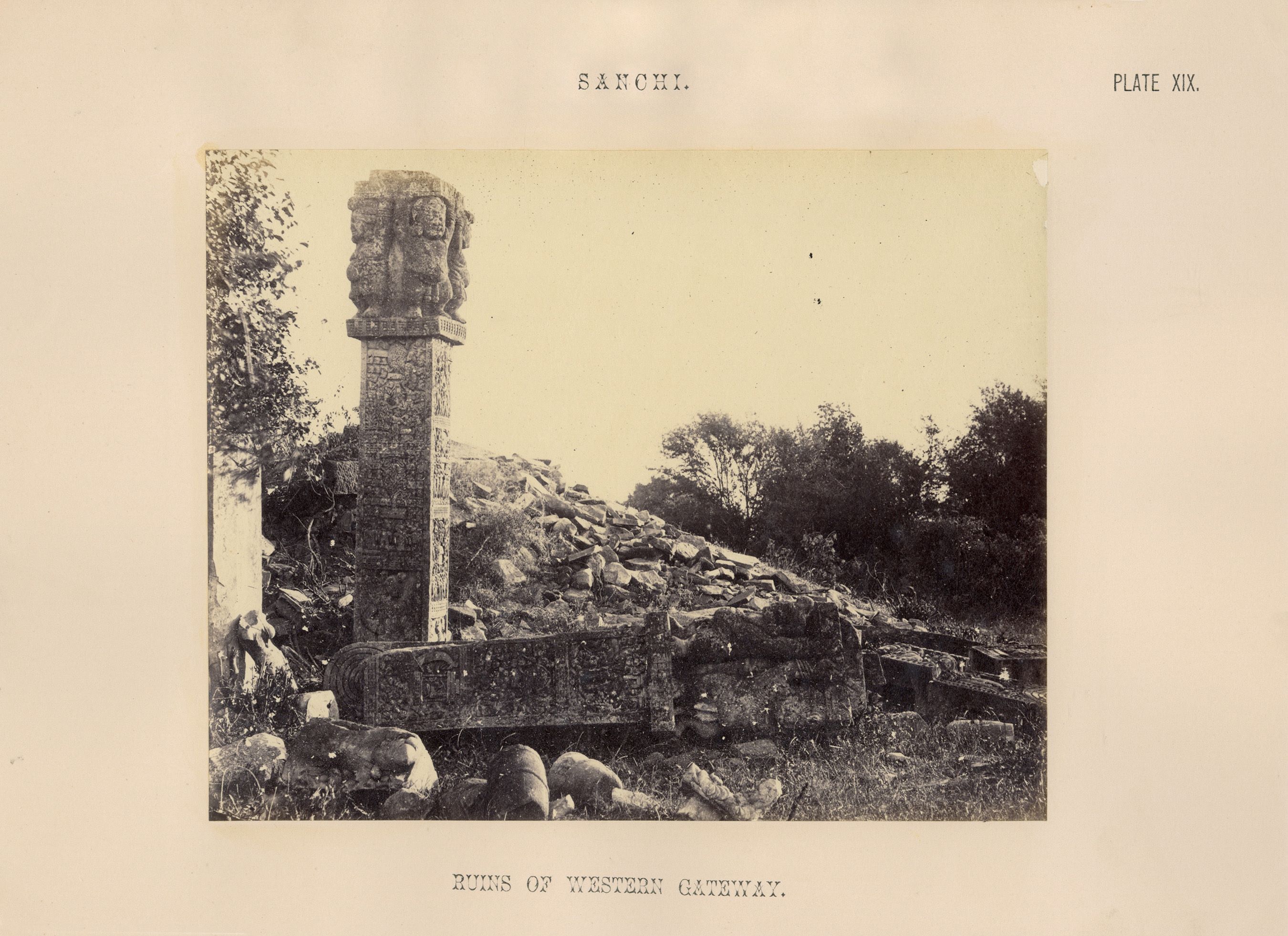

James Waterhouse Plate XIX. Ruins of Western Gateway, Sanchi (The Great Stupa, Sanchi) Silver albumen print, December 1862 6.2 x 8.0 in. / 15.7 x 20.3 cm.

|

James Waterhouse

Plate XIX. Ruins of Western Gateway, Sanchi (The Great Stupa, Sanchi)

Silver albumen print, December 1862

6.2 x 8.0 in. / 15.7 x 20.3 cm.

Collection: DAG

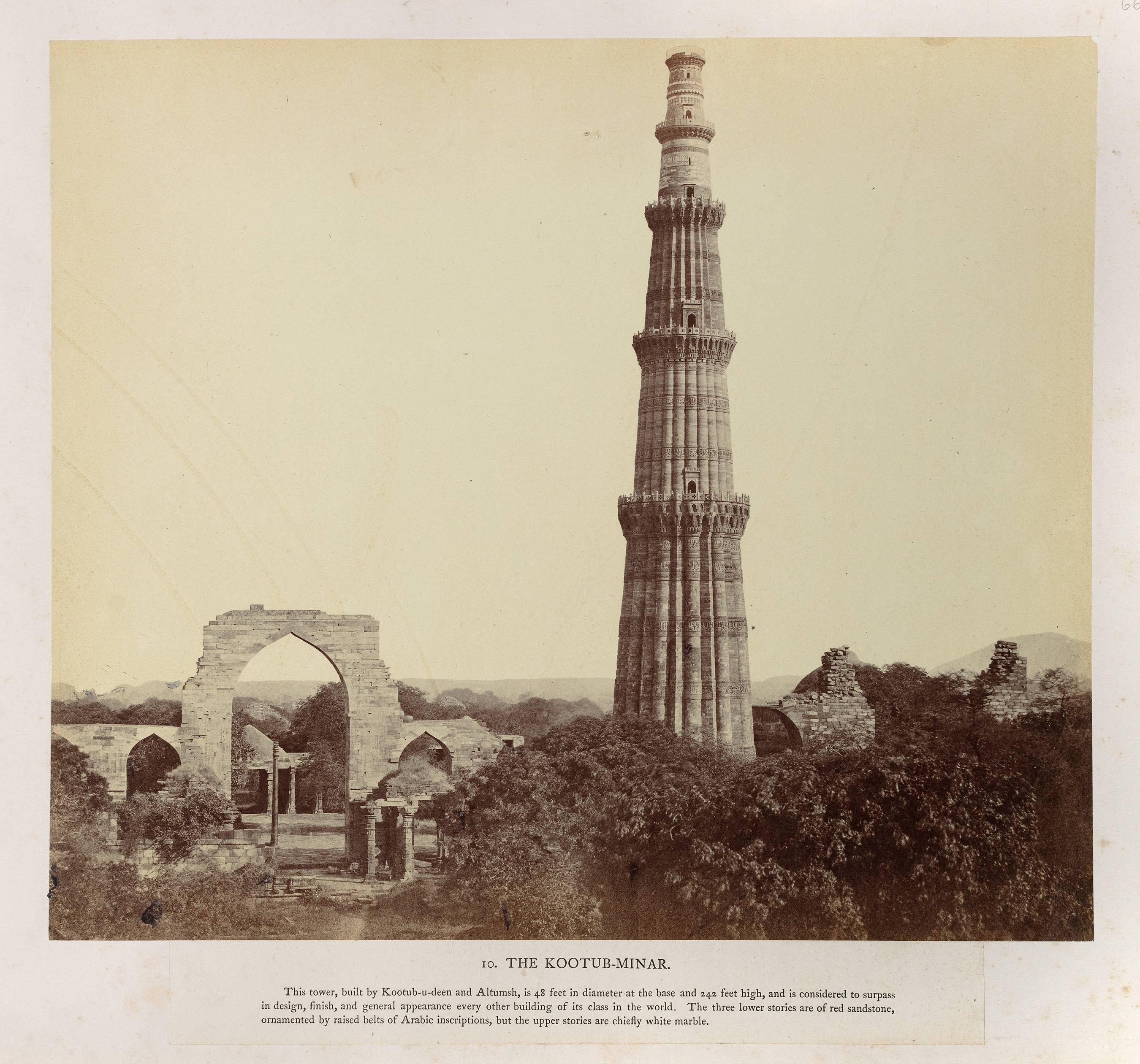

Eugene Clutterbuck Impey

The Kootub - Minar (Qutub Minar, Delhi)

Silver albumen print, c. 1858–65

9.5 x 11.0 in. / 24.1 x 27.9 cm.

Collection: DAG

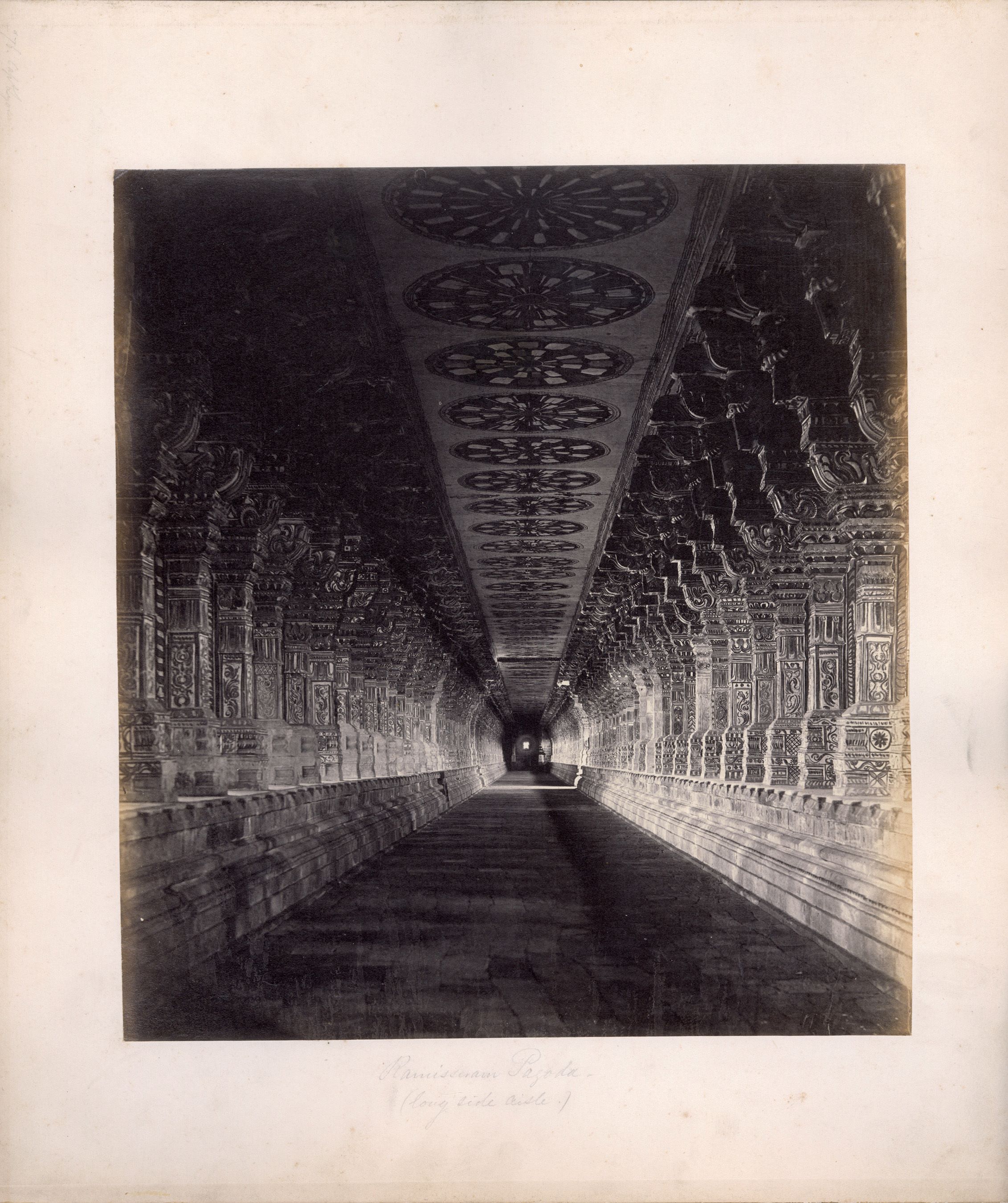

Edmund David Lyon

Ramisseram Pagoda (Long Side Aisle) (Ramalingeswara temple, Rameswaram)

Silver albumen print, 1867–68

10.5 x 9.5 in. / 26.6 x 24.1 cm.

Collection: DAG

|

|

SELLING THE PICTURESQUE

|

|

Samuel Bourne and James Craddock A View on the Dal Canal, Kashmir Silver albumen print, c. 1860 9.2 x 11.5 in. / 23.4 x 29.2 cm.

|

Samuel Bourne and James Craddock

A View on the Dal Canal, Kashmir

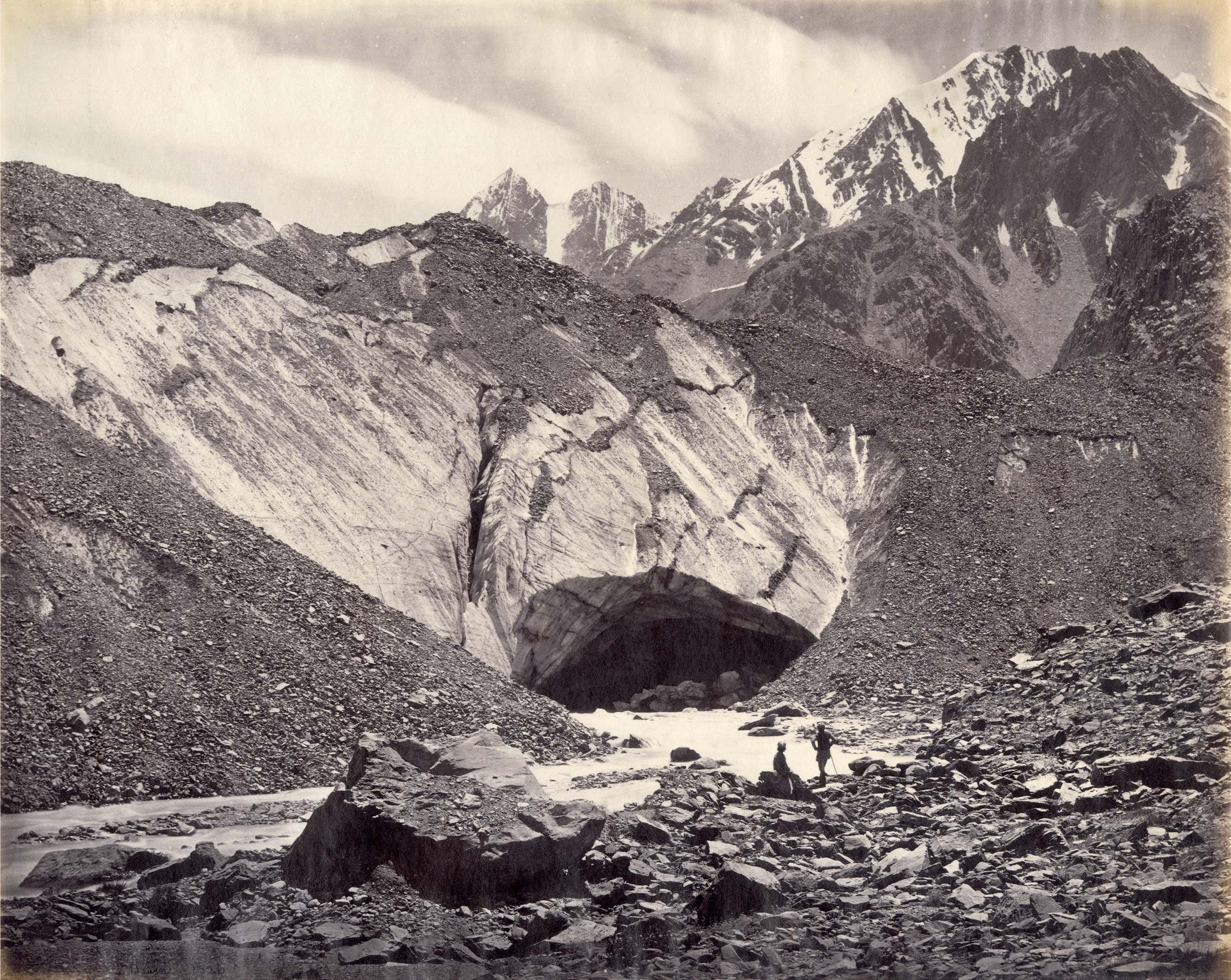

Samuel Bourne

Ice cave, Source of the Buspa

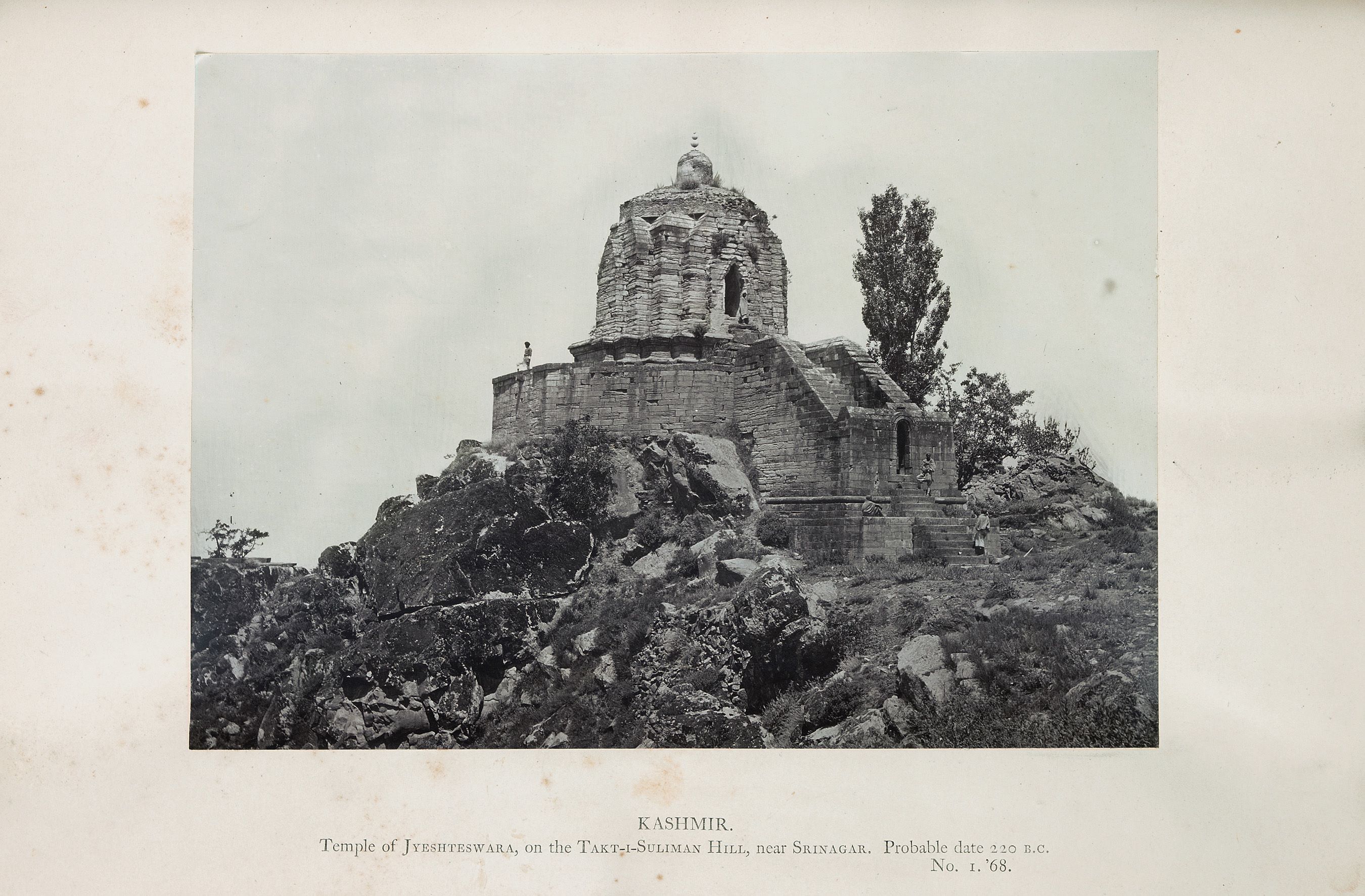

Samuel Bourne

Shankaracharya Temple, Takht-i-Sulaiman Hill, Kashmir

|

CONTESTING THE EMPIRE

|

|

Narayan Vinayak Virkar Samathi (Samadhi), Raigad Fort Silver gelatin print, c. 1919 8.0 x 6.0 in. / 20.3 x 15.2 cm.

|

Narayan Vinayak Virkar

Samathi (Samadhi), Raigad Fort

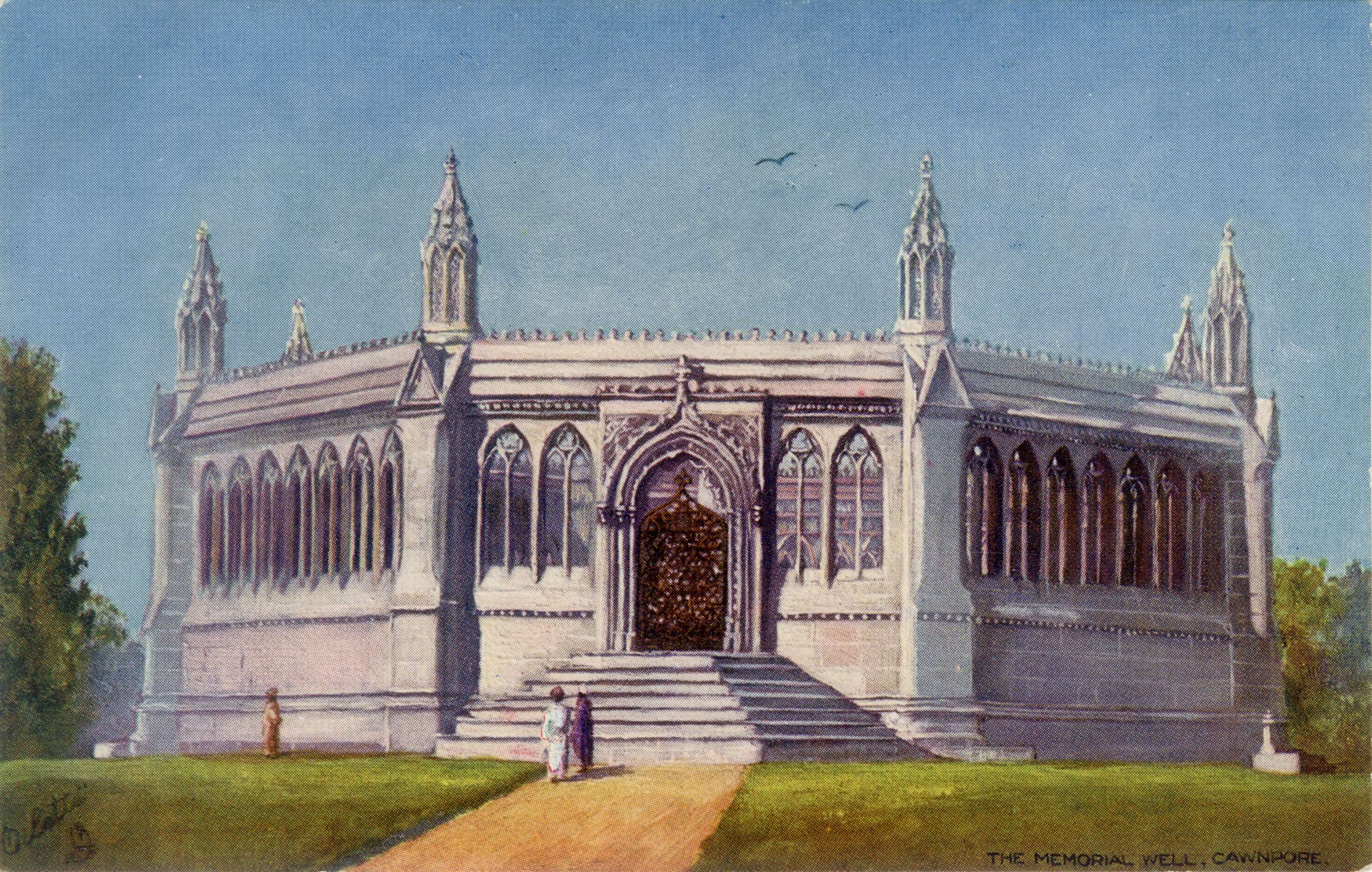

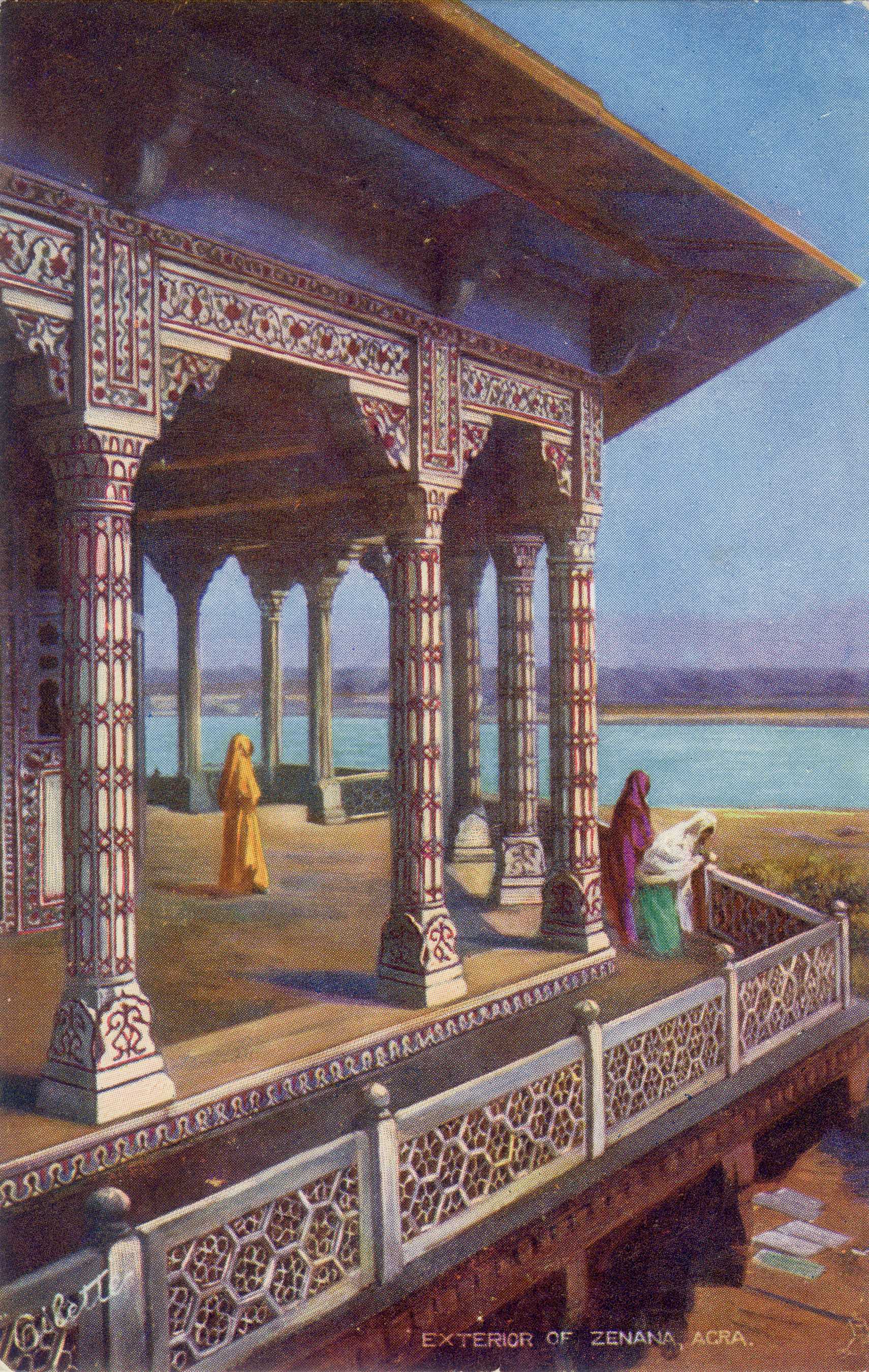

Raphael Tuck & Sons #7234, London

The Memorial Well, Cawnpore

Raphael Tuck & Sons #7237, London

Exterior of Zenana, Agra

|

PHOTOGRAPHY AS CURRENCY

|

|

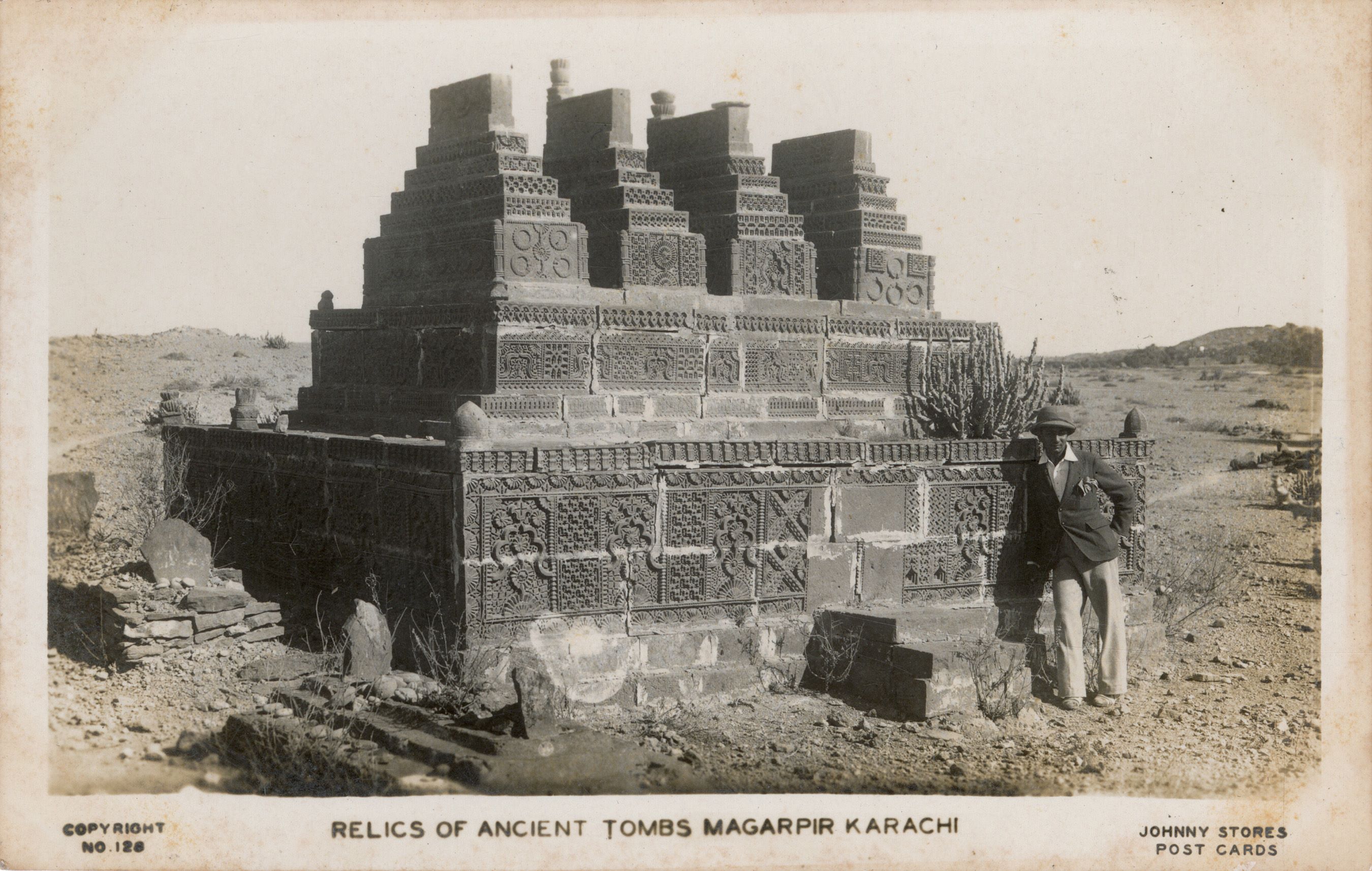

Johnny Stores post cards, Karachi Relics of Ancient Tombs Magarpir Karachi Real photo postcard, divided back, c. 1920 3.4 x 5.4 in. / 8.6 x 13.7 cm.

|

Johnny Stores post cards, Karachi

Relics of Ancient Tombs Magarpir Karachi

Underwood & Underwood

Stereoscope

Oak, tin, glass and velvet, 1901

Gobindram Oodeyram, Chandpol Bazar, Jeypore, Rajputana

Printed card, early 20th century

|

“The exhibition builds upon the connected history of photography and field surveys of India’s past to display the power and authority of the photograph and photographic collection as historical objects to think with.” - Sudeshna Guha |

Presented by