From 'Mappa' to 'Manchitra': Exploring the maps of Calcutta

From 'Mappa' to 'Manchitra': Exploring the maps of Calcutta

From 'Mappa' to 'Manchitra': Exploring the maps of Calcutta

collection stories

From 'Mappa' to 'Manchitra': Exploring the maps of CalcuttaSoumava Das Kolkata, one of the most thoroughly surveyed cities in India, has been viewed, reflected upon, and annexed in varying degrees of detail in the colonial repositories of information about India. Cartography, as a discipline, creates a network that generates a common widespread idea of map-making to create a singular form of spatial knowledge of places or the whole world as part of the progressive modern knowledge system. |

James Baillie Fraser

View of Calcutta from the Glacis of Fort William

c. 1826, Engraving and aquatint, tinted with watercolour on paper, 13.7 x 19.7 in.

Collection: DAG

|

Maps as cultural texts As J. B. Harley reminds us, a map is not merely a topographic mirror of a land, but a cultural text, or a description of the complex social and political world. It is a transcultural endeavour of translating the world onto paper or screen by assembling signs such as a ‘data frame’ that collates information about various geographic elements (for example, forest area) and their density (often through various shades of one colour or by repeating the same sign multiple times), among other things. It entails how the map-maker viewed the world–what they felt was important, what priorities were established, and what values they chose to insert into the map. |

|

|

Calcutta Map from 1900 A.D.

Kolikata Street Directory, 1916

Image courtesy: P. M. Bagchi, Kolkata

The ambition of building a portable knowledge repository and its dissemination resonates with the colonial history of India. Not only did a large number of painters, printmakers, and photographers gathered there in the eighteenth century to produce 'views' of the 'orient', several British military academies and colleges also took the initiative to train their pupils in drawing, photography and survey methods. Most surveyors were military personnel as there was no separate training school for surveyors. The East India Company would not trust anyone not part of the civil and military services; hence, it was assumed that every engineer officer would be capable of surveying. Matthew H Edney states, 'Cartography… appears to be at once a practice found in all socially complex cultures and a particular historical formation associated with Western imperialism'. |

|

Early maps of Calcutta A close look at a few early maps helps us understand how the representations of places in Calcutta (now Kolkata) were configured in the cartographic projects of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. |

|

|

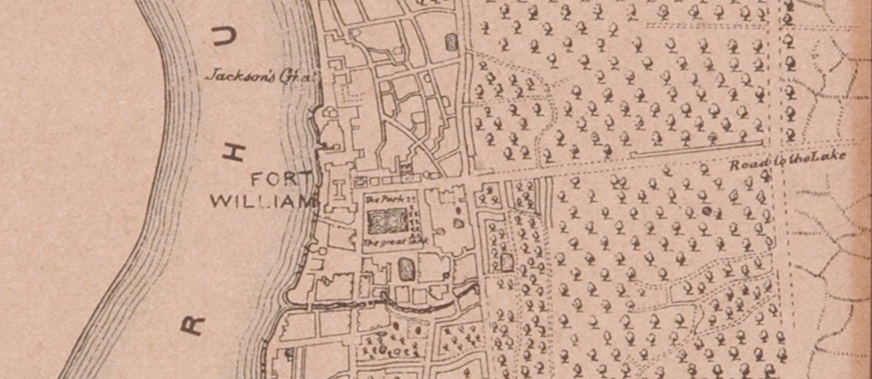

Plan of the City of Calcutta in 1742

Image courtesy: Victoria Memorial Hall, Kolkata

Plan of the City of Calcutta in 1742 (detail)

Image courtesy: Victoria Memorial Hall, Kolkata

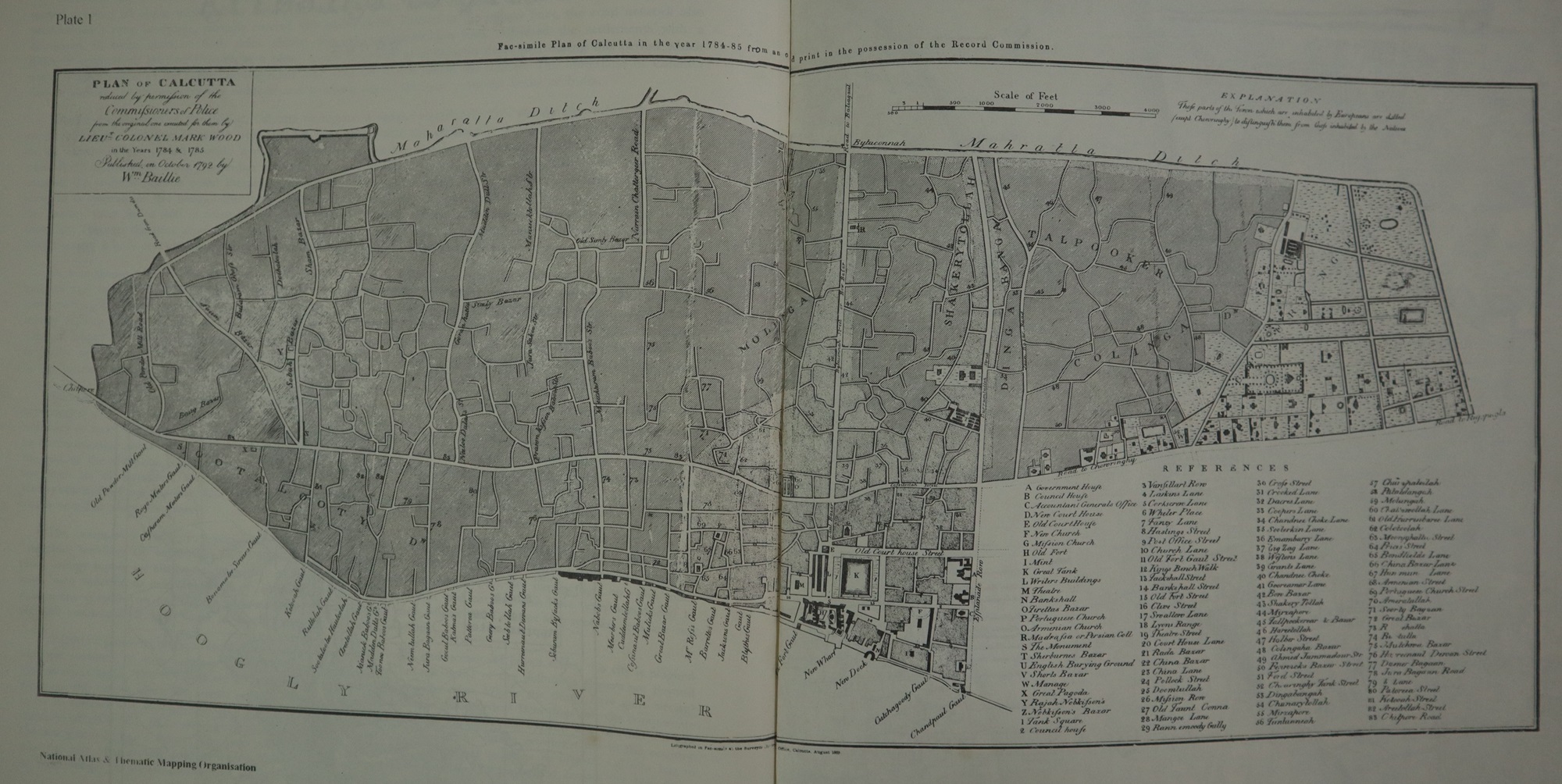

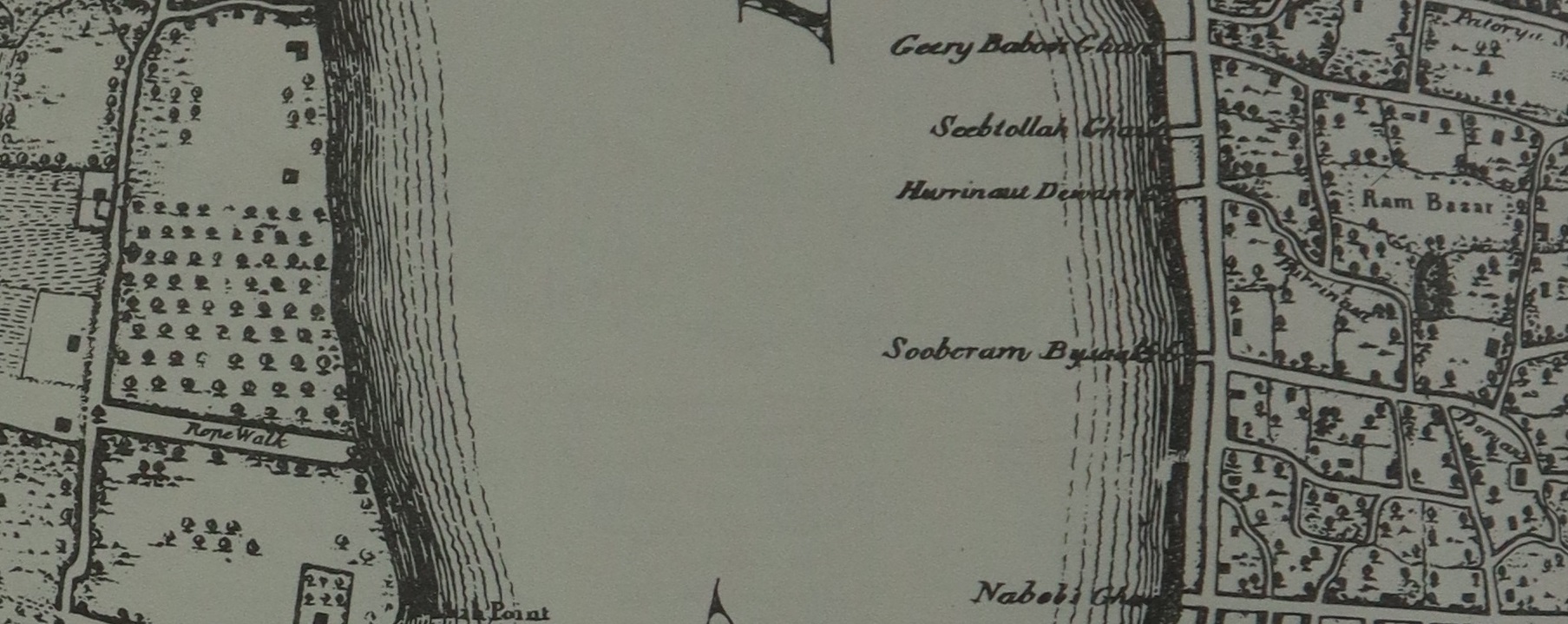

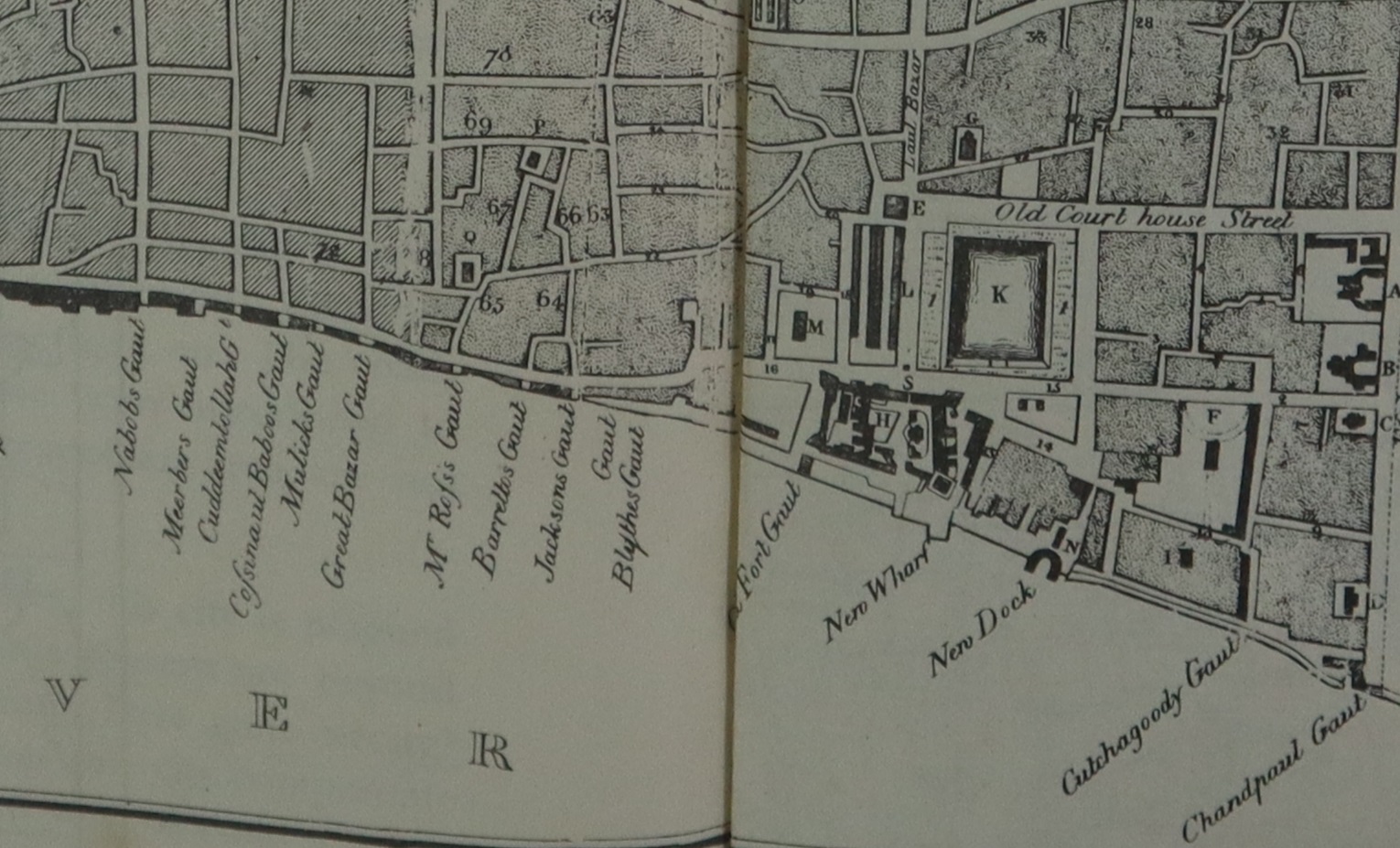

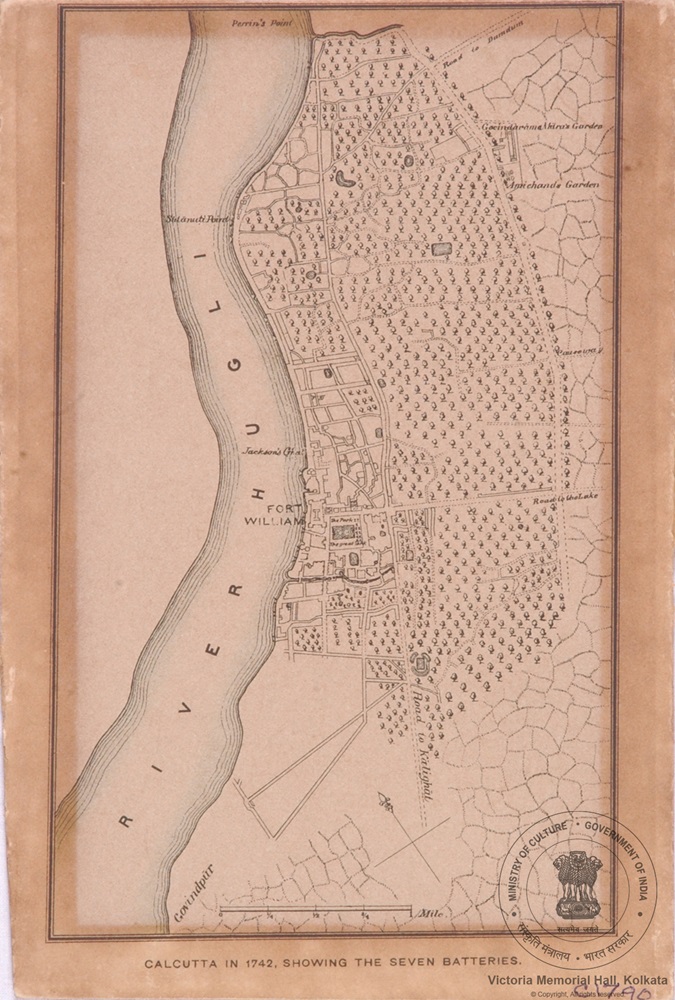

One of the earliest maps of the region was ‘Calcutta in 1742, showing the Seven Batteries’. The map shows a cluster of inhabited places near Fort William by marking it with capital letters and leaving most of the city unmapped or rather full of trees with a hint of three settlements, Govindapur, Kalikata, and Sutanuti—the three villages that eventually became the city of Calcutta. Here, the focus on topographical specificity makes evident that the purpose(s) of mapping the city shifted with the changing needs of colonial power. Eventually the focus on defence and fortification broadens to accommodate other administrative needs and as such, street names, administrative buildings, and even important houses of Englishmen start appearing on maps. |

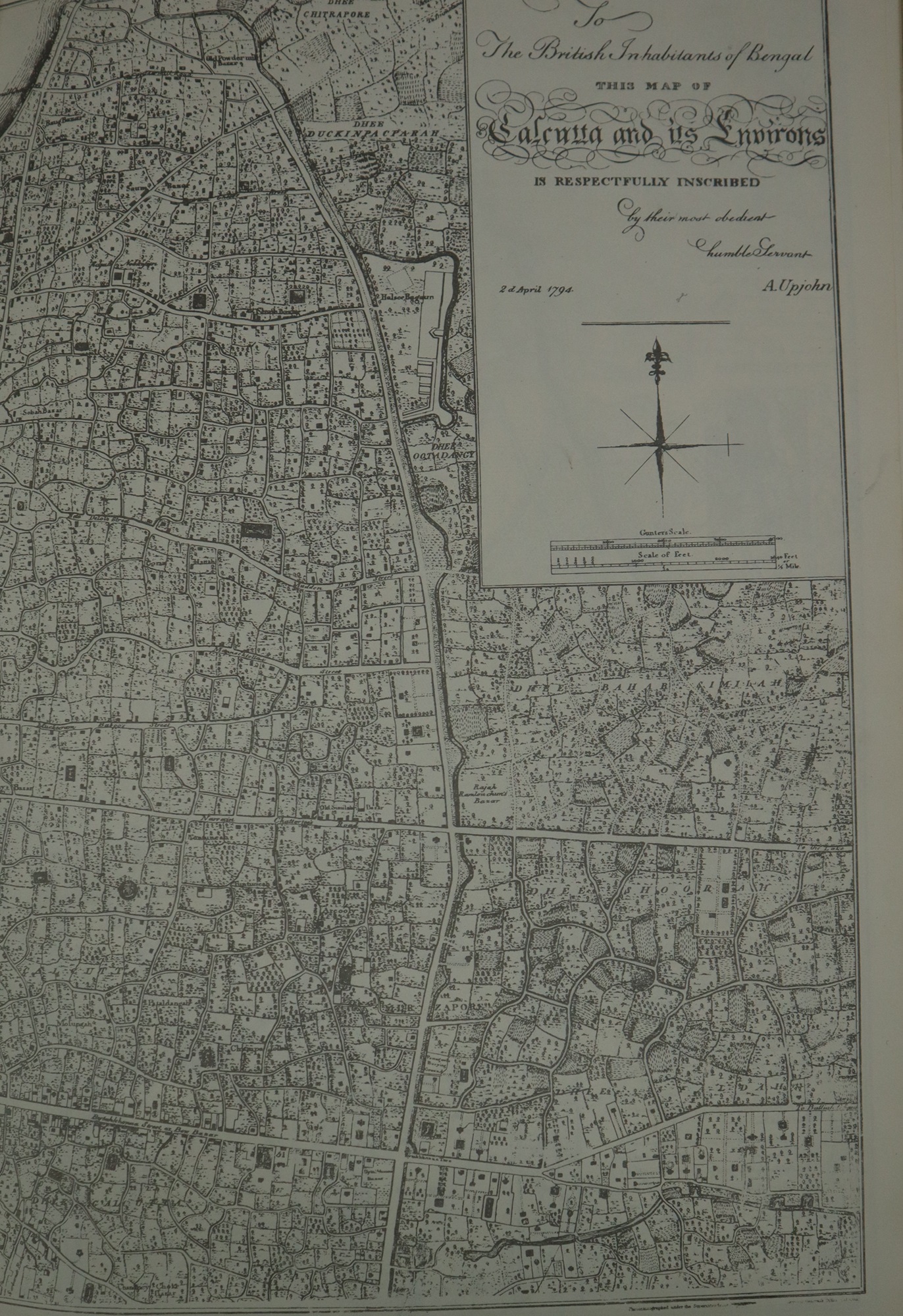

Aaron Upjohn's map of Calcutta, c. 1793

Wm. Baillie's 'Plan of Calcutta'

Aaron Upjohn's map of Calcutta, c. 1793 (detail)

Wm. Baillie's 'Plan of Calcutta' (detail)

|

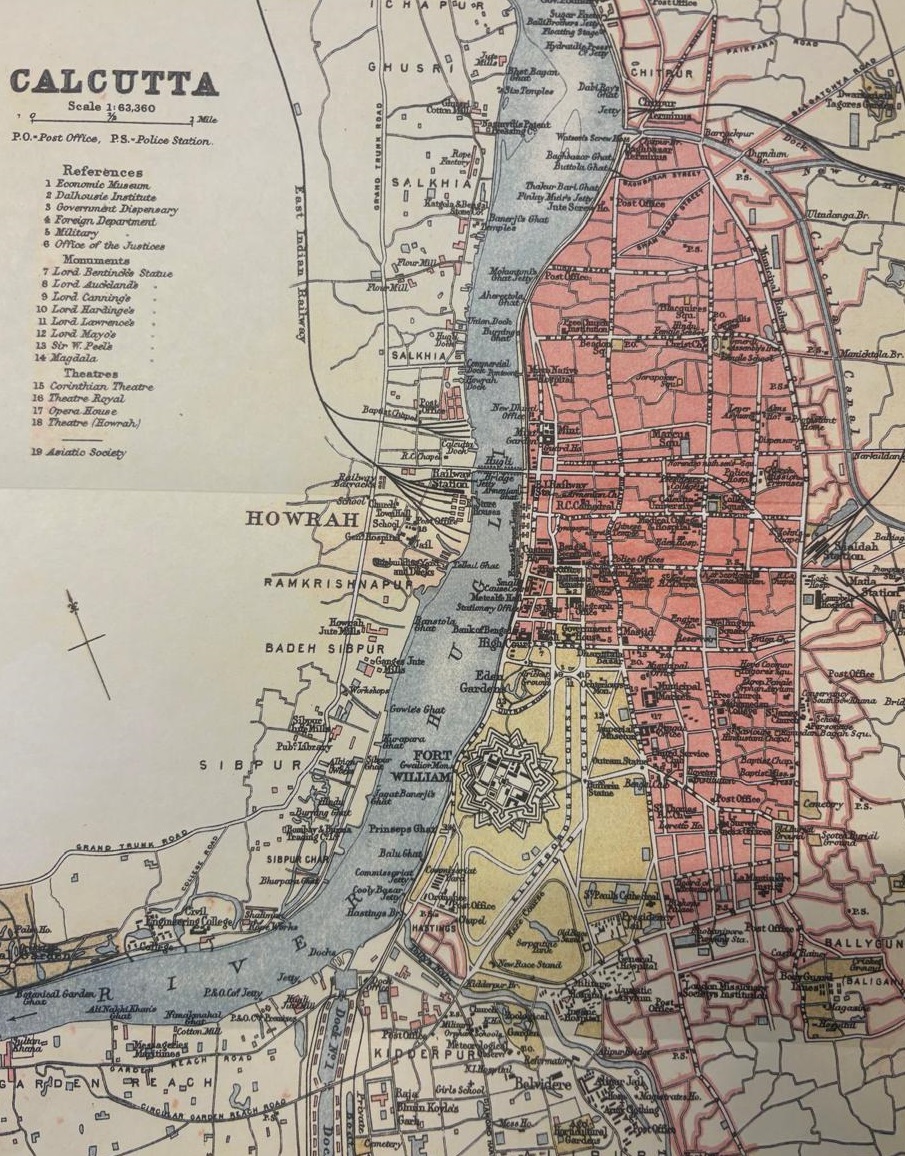

Making visible through mapping The consequence of mapping specific parts of the city leads to the visibility of those areas as well. By the first half of the nineteenth century, multiple health threats came up. The Lottery Committee came into being in 1817 for the purpose of improving the non-European localities, especially congested areas such as the markets including the Barra Bazar, planning big roads keeping in mind the motorized future of the city and sewage system through the crowded places, and eventually, commissioning a new map for Calcutta. |

|

|

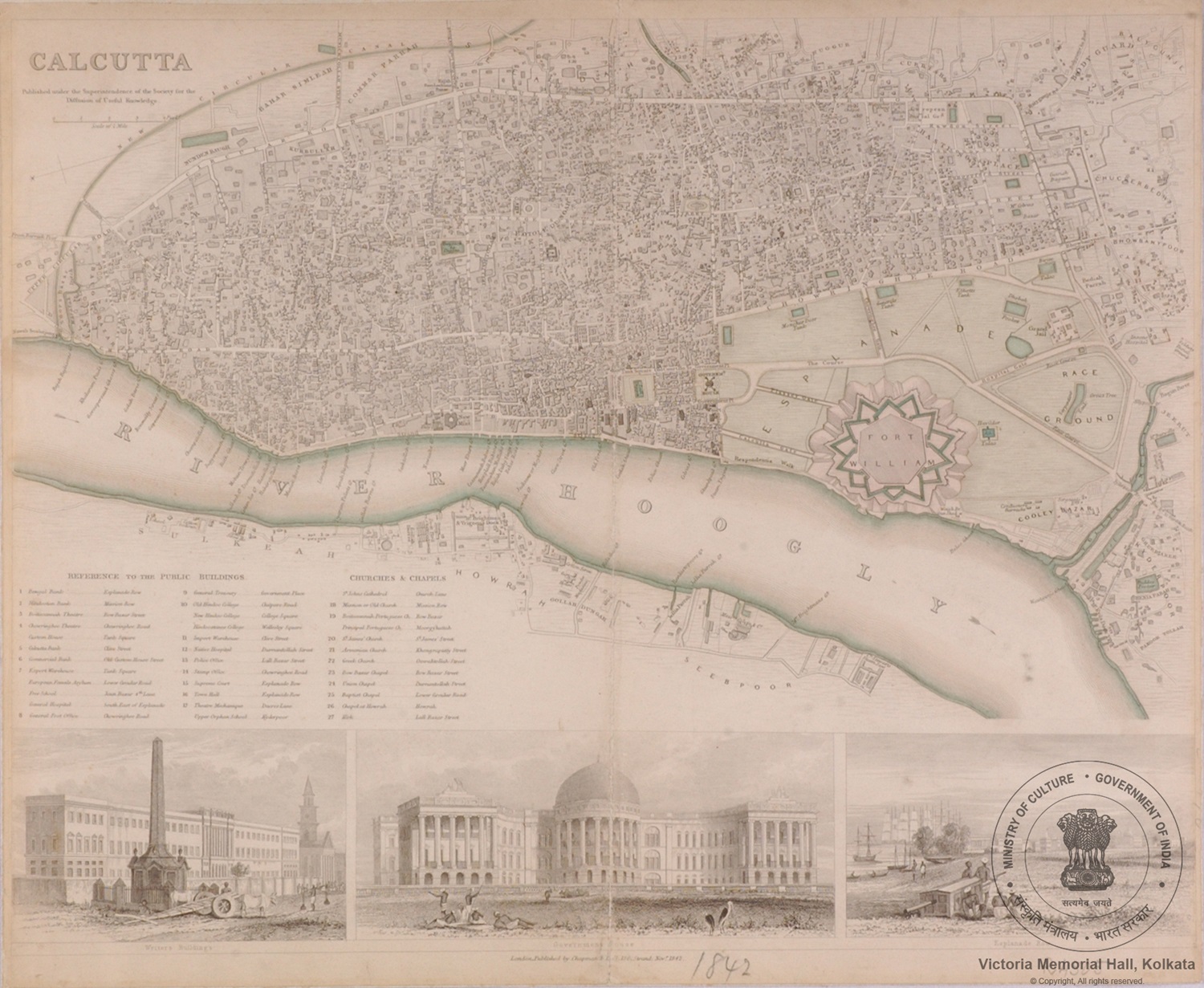

S.D.U.K. Map of the City of Calcutta, India

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Thomas Daniell

The Writers' Buildings, Calcutta

1798, Engraving on paper, 18.0 x 23.7 in.

Collection: DAG

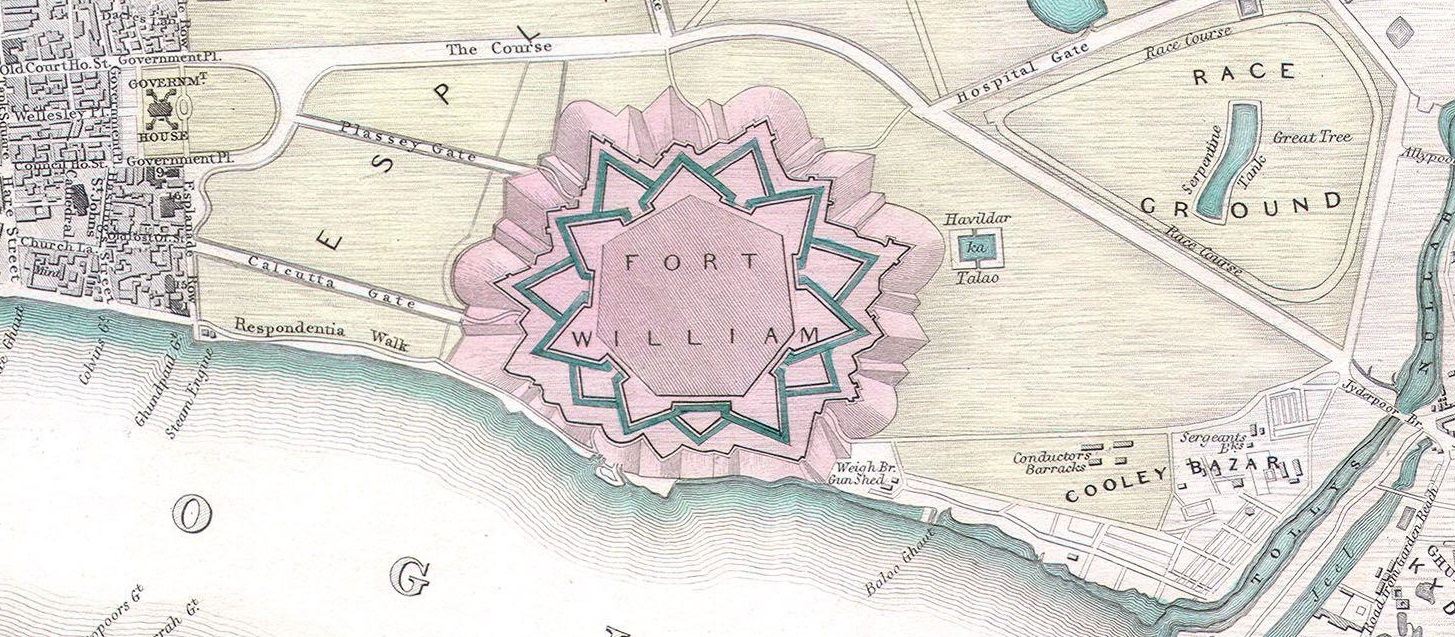

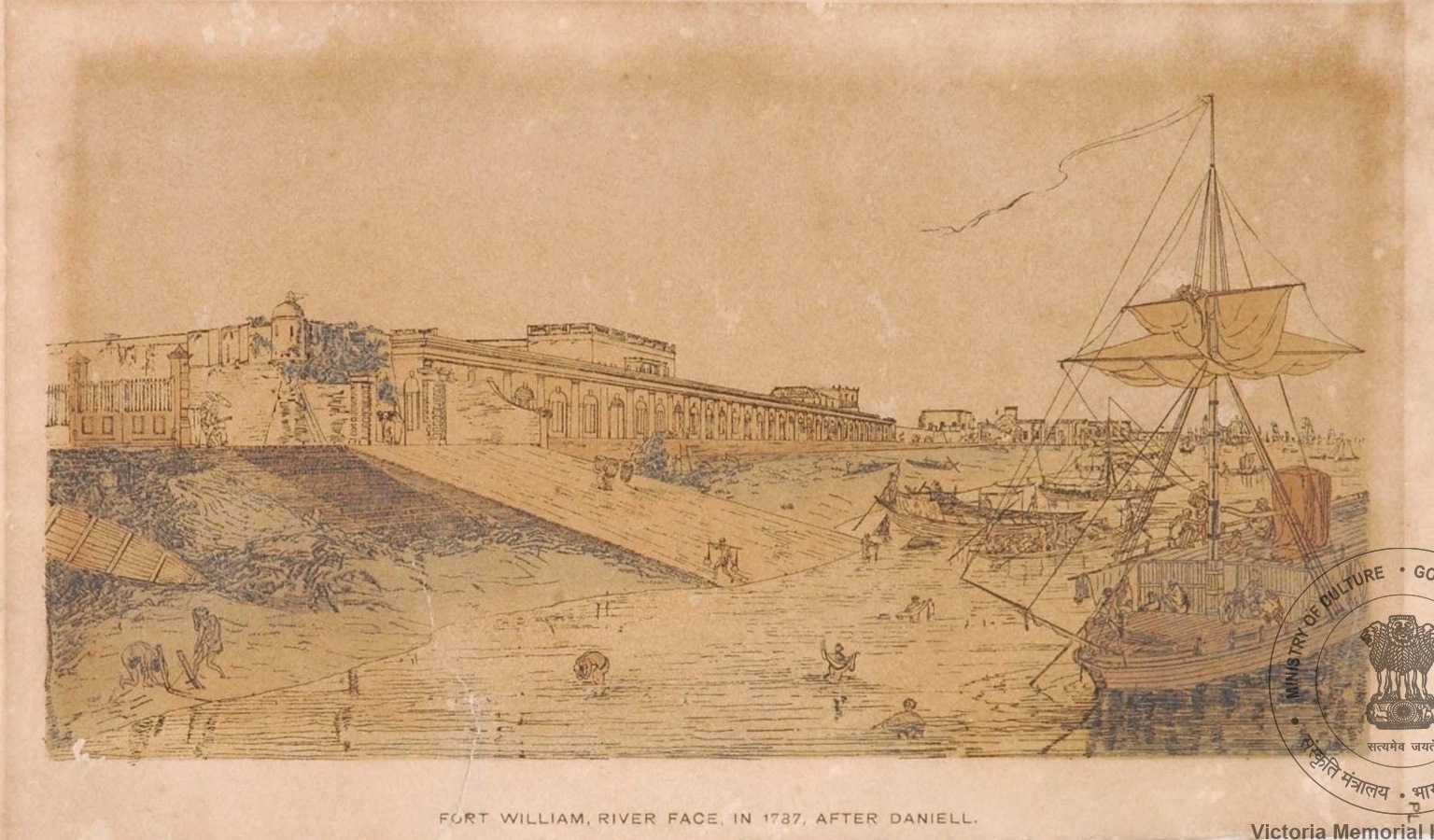

Even in the more detailed maps, an interesting commonality emerges in the way the topographical representation is configured. Fort William, in the form of text and images, occupied a crucial position in almost all the maps. With time the representation of it changes and visually became more pronounced on the maps. This position of Fort William as an anchor in representations of Calcutta’s topography found in maps is a feature shared with landscape paintings made by European artists. The maps, although considered a scientific enterprise, were put in conversation with such paintings in various publications. The Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (S. D. U. K.), set up to encourage amateur studies in topography and map-making, incorporated several landscapes portraying the Governor House, the Writers Building, etc. in the map of Calcutta, in their publication of 1842. |

Fort William detail from S. D. U. K. map

Thomas Daniell

View of the Esplanade, Calcutta before 1800

Thomas Daniell

View of the riverside of the old Fort William

|

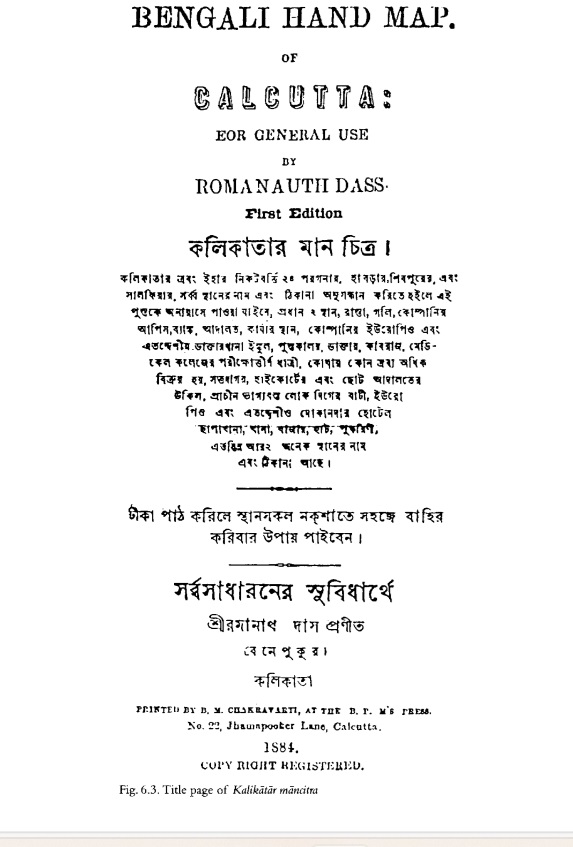

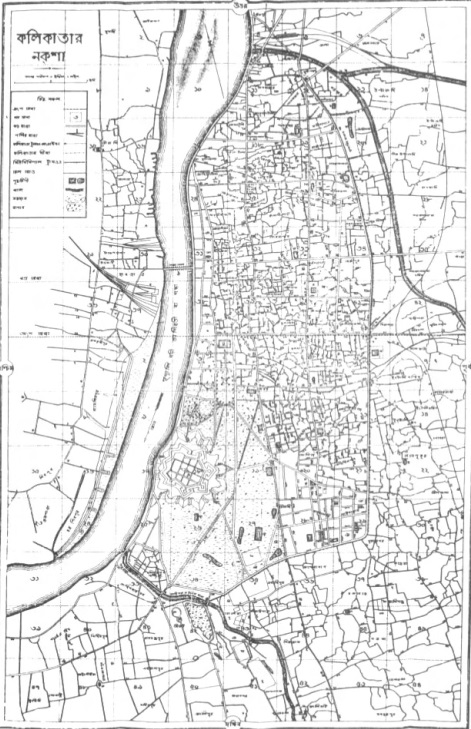

Alternative cartographies In the second half of the nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth century, many vernacular maps and street directories were published, of which, Ramanath Das's Kalikatar Mancitra, a map-cum-guidebook in Bengali, published in 1884, was a distinctive, pioneering endeavour. Compared with the English maps and directories of the city, it stands out because of its attempt to develop an alternative cartographic and classificatory method of listing information. In this, Ramanath Das had to contend with the fundamental issue of the role of cartography in the new, urban culture of Bengal. |

|

|

Ramanath Das

Kalikatar Mancitra, 1884

Image courtesy: Archive.org

Ramanath Das

Kalikatar Mancitra, 1884

Image courtesy: Archive.org

Das clarifies his stance in an introductory note: 'For the use of the "common people" a book entitled Kalikatar Manachitra (Bengali Hand Map), along with a map of the city, has been written in the Bengali language. The names and signs provided in the book, along with the signs given in the map will enable one to locate all places, roads, lanes, gaits, offices of the company, banks, courts, work places, European and Indian medical stores, schools, doctors, kabiraj, midwives who have passed out from the Medical College, main concentration of things sold, traders, lawyers of the high and lower courts, residences of "affluent people," European and Indian shops, hotels, presses, police stations, bazars, hats, ponds, as well as location of several other places.' |

|

Another initiative was taken by notable polymath Rajendralal Mitra under the title The Bengal Atlas: A series of Original and Authentic Maps of Most of the Districts Included of the Lieutenant Governorship of Bengal. Mitra’s atlas was pathbreaking in many ways as he incorporated vernacular names in the maps and used the Bengali metric system (‘krosh’) in his cartographic method. Moreover, he pays close analysis to the nomenclature of the words- ‘map’ and ‘manchitra’ and explains that the word ‘map’ originates from the Latin word ‘mappa’ that means napkin, while ‘manchitra’ stands for a measured image of land. |

|

|

|

P. M. Bagchi published another street directory of the city—‘Kalikata Street Directory 1915’, which followed in the practice of vernacular cartographies. These vernacular maps and directories added a different dimension to the discourse of knowing and depicting the city as they are made for the use of the common people, for whom navigating the intricate streets, alleyways and neighbourhoods became a core, everyday concern. |

|

|