From Figuration to Abstraction: Highlighting the Madras ModernThe Editorial Team June 01, 2024 Some of the historians of the Madras Modern art movement emphasise the importance of location and tradition in its construction. Individual practitioners, however, were free to experiment within a broad parameter of values—going back to a figure as individualistic as D. P. Roy Chowdhury, whose artistic roots were more widespread than that of his colleagues at the Madras art school at the time. Post K. C. S Paniker’s tenure at the art school in Madras (now Chennai), however, his experiments did not disappear but were transmuted by the synthetic practices adopted by abstractionists too. In this essay we will focus on three important figures in the Madras Modern art movement: D. P. Roy Chowdhury, L. Munuswamy and V. Viswanadhan. |

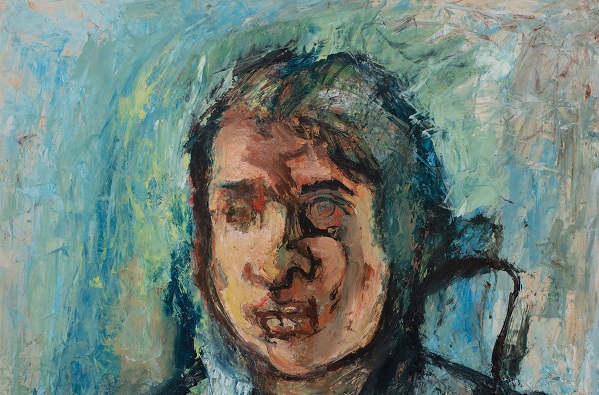

L. Munuswamy

Young Girl (detail)

Oil on paper, 29.5 x 24.7 in.

Collection: DAG

|

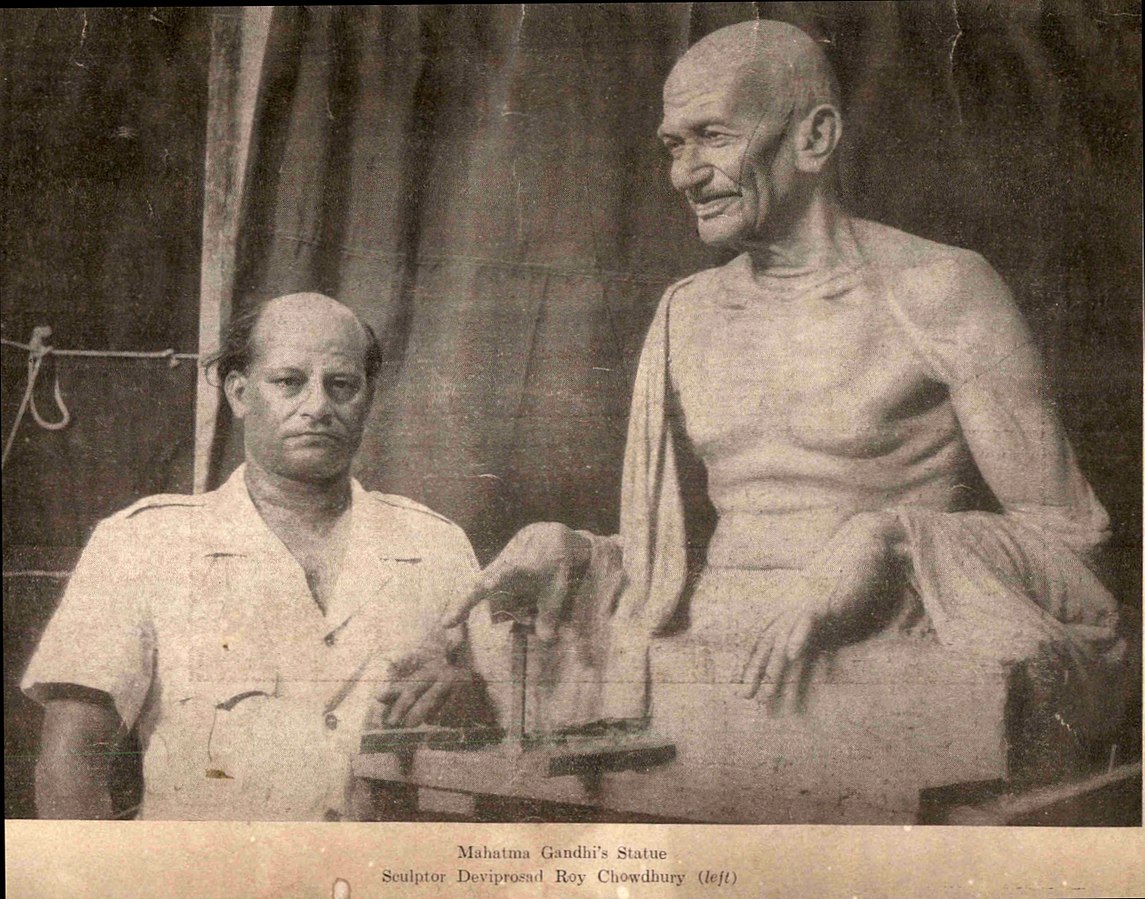

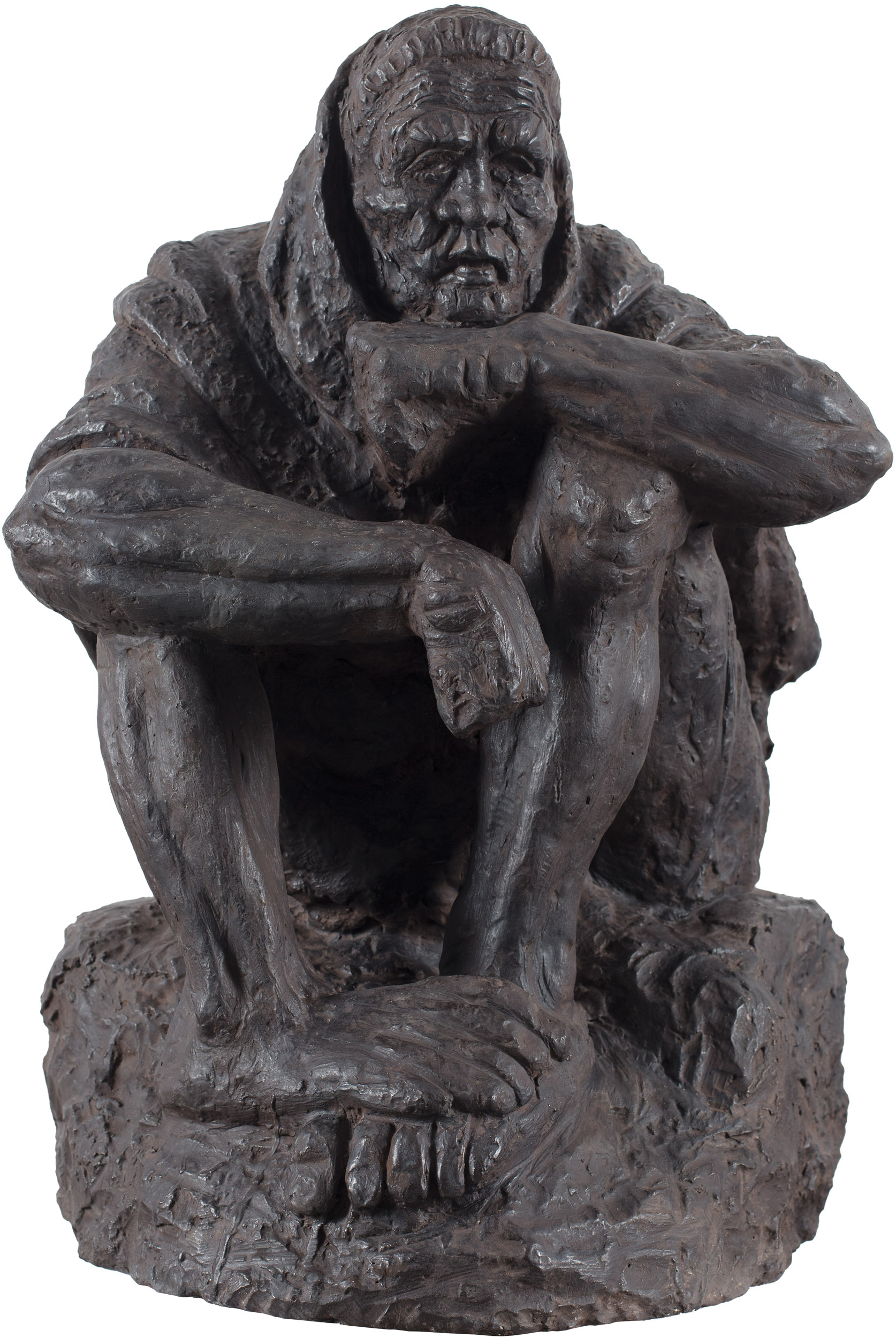

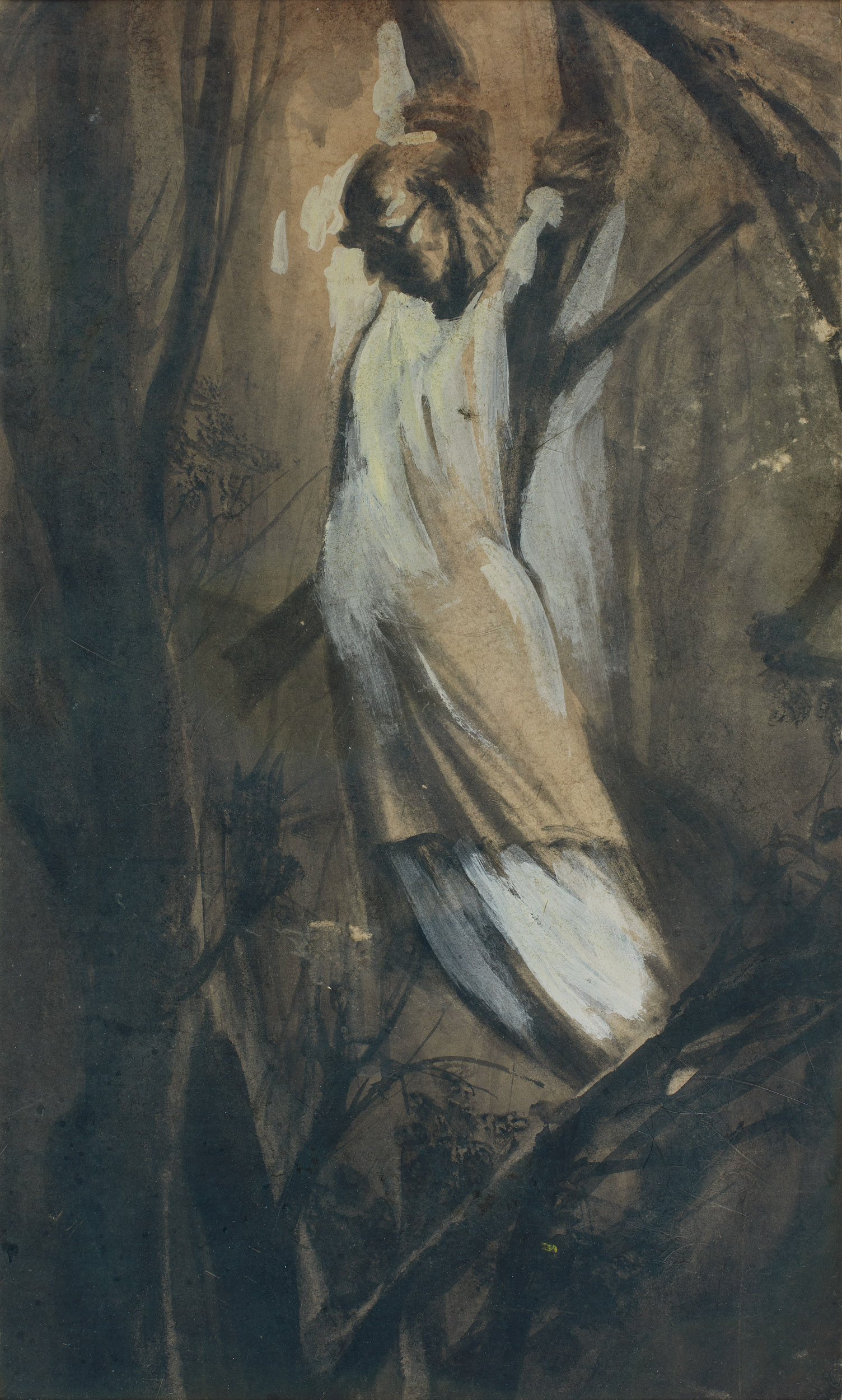

D.P. Roy Chowdhury (1899-1975) D.P. Roy Chowdhury was a prominent Indian artist known for his paintings and sculptures. He joined the Madras College of Art as a student in 1928 and later became its principal. Roy Chowdhury learnt painting from Abanindranath Tagore and sculpting from Hiranmoy Roychoudhuri, with later training in Italy. He evolved his skills in bronze casting and executed paintings that were an amalgam of Chinese technique, Japanese wash process, and his own scratching method. He tended towards romantic imagery in his work, and according to Jaya Appasamy, was often described (inaccurately, in her opinion) as ‘traditionalist’ or ‘academic’. |

|

|

D. P. Roy Chowdhury

The Sentinel

Gouache, gravel and adhesive on board, 20.0 x 12.2 in.

Collection: DAG

D. P. Roy Chowdhury

Dark Shadow

Gouache on paper, 13.5 x 9.7 in.

Collection: DAG

D. P. Roy Chowdhury

Untitled

Gouache on paper, 13.7 x 17.7 in.

Collection: DAG

Like Abanindranath he was a multi-hyphenate talent, excelling not just as an artist, but also as a popular writer of fiction, a wrestler and also a musician who played the flute. During his tenure as Principal at the Madras College of Art, he is said to have trained his students in the art of wrestling as well, for which purpose an akhada (wrestling pit) was dug behind his residential quarters. In spite of his aristocratic origins—his father owned a large estate in Diamond Harbour—Roy Chowdhury wrote about the lives of working class men and women in his stories, consciously committing himself to a socialist principle of imagining a community or a people over individual self-expression. However, he also wrote many stories of hunting, an activity he engaged in himself, which contained lush descriptions of forests and mysterious evocations of ghostly environments that included dilapidated palaces or ruined temples in the countryside. His drawing room contained several musical instruments, expensive Persian rugs and ‘a couple of stuffed tiger heads shot by him’. |

D. P. Roy Chowdhury

The Modern Review

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

D. P. Roy Chowdhury

When Winter Comes

Plaster of paris, 21.0 x 16.0 x 20.0 in.

Collection: DAG

D. P. Roy Chowdhury

Shikari

Gouache and ink on paper, 13.5 x 8.0 in.

Collection: DAG

Towards the end of his life, when he rarely held public exhibitions of his work even as he continued to work regularly in his own studio, he is reported to have said, ‘l consider my modest studio… as a sort of old, sacred temple devoted to the cause of art. I worship the objects I create. I can never think of them being carried now and then for public view. Those who are real lovers of art are welcome to my studio. Don’t the devotees pay a visit to the dilapidated temple in a village?’ Noting some of the contradictions in his personality and work, Appasamy wrote, ‘Roy Chowdhury is a paradox. He is an aristocrat and never meets anyone without prior appointment. He does not attend a telephone call while in his studio. But once the visitor arrives he finds the artist charming and is impressed by his scintillating conversation, ready wit and above all a certain naivete. Five foot eight inches tall with a 48 inch chest, 74 year old Roy Chowdhury baffles the younger generation with his imposing Roman stature, vigour and carriage. He is a man of regular habits and works for more than ten hours a day. A great host, he enjoys entertaining a select company. Roy Chowdhury is fond of children and keeps a stock of sweets ready for them. Save for his studio and work, Roy Chowdhury is unmindful of other things ; his worldly affairs are managed by his charming wife Charulata.’ |

|

As principal of the Madras College of Art, Roy Chowdhury chose his figures from the crowd in the streets in preference to studio models. His sculptures ranged from busts and life-sized statues to larger-than-life-size works, including notable public works like the Dandi March in New Delhi and the Triumph of Labour sculpture in Chennai. Roy Chowdhury was honoured with the Padma Bhushan in 1958 and an honorary doctorate from Rabindra Bharati University in 1968. He believed that ‘A thing of beauty made, radiates its virtues not only to one who claims to be the creator, but also to those who are endowed with receptive quality.’ After Roy Chowdhury's retirement in 1957, K. C. S. Paniker became the principal of the Madras College of Art. |

|

|

|

L. Munuswamy (1927-2007) L. Munuswamy was a prominent artist and teacher who played a key role in the Madras Art Movement. He received his diploma from the Government School of Arts & Crafts, Madras in 1953 and later served as the Principal. Munuswamy was known for his abstract paintings and was considered one of the pillars of the Madras Art Movement, along with K.C.S. Paniker. As an artist-teacher at the Madras School of Arts and Crafts, he guided many painters of the Movement. Munuswamy and other artist-teachers at the institution played a crucial role in its development through their creative and technical explorations. |

|

|

L. Munuswamy

Untitled

Oil on paper, 30 x 24.7 in.

Collection: DAG

L. Munuswamy

Young Girl

Oil on paper, 29.5 x 24.7 in.

Collection: DAG

He was one of the abstractionists who emphasised the need for ‘source(s) of reference’ and foregrounded skill in the act of creation. For him, therefore, the movement towards abstraction was not completely free of a linguistic framework. He was an admirer of the poet Rabindranath Tagore and held him to be a ‘forerunner of modern art long before Picasso and others’. It signals a tendency within the movement where the sources for artmaking were sought within the traditions and forms of vernacular/regional languages—an especially pressing, political gesture in the 1950s and early 60s in India when language rights were being employed as bases for regional-state unities that sought to add further layers of identity to the overarching national one. The States Reorganisation Act, securing linguistic unity within states, was passed in 1956. Writing about his female figures, Ashrafi S. Bhagat notes, ‘The strength of his abstraction lay in defining a regional link to his Indian roots derived from women peculiar to Tamil Nadu… (t)hough his female forms have universal appeal, nevertheless they are set in the Indian tradition in regard to their attitudes and postures, attire and physiognomy, accompanied by birds and animals.’ |

L. Munuswamy

Untitled

Oil on paper, 28.2 x 22.5 in.

Collection: DAG

L. Munuswamy

Wild Life

Gouache on paper , 1960, 25.0 x 29.5 in.

Collection: DAG

Munuswamy's artistic style was characterized by an international, abstract expressionist approach, with a focus on line, colour, and space. He consciously chose abstraction as his artistic language, allowing regional influences to play a meaningful role in his work. Munuswamy's abstract paintings often featured the human form as a dominant motif, through which he mediated his abstract expressions; and equally, perhaps due to his origins in a family of idol-makers, he bore a lifelong interest in craft traditions and natural motifs—thereby drawing a line back to the romantic imagination of Roy Chowdhury. In 1968, Munuswamy won the National Award from the Lalit Kala Akademi, New Delhi, and in 1976, the State Award from the Tamil Nadu Ovia Nunkalai Kuzhu, Madras. His works are part of prestigious collections such as the National Gallery of Modern Art in New Delhi, the Lalit Kala Akademi in New Delhi, and the State Lalit Kala Akademi in Chennai. He was appointed Principal of the Madras Government School of Arts and Crafts in 1971, a position he held until his retirement in 1986. |

|

From Roy Chowhdury to Paniker and Dhanapal, Munuswamy paid tribute to them when he said, ‘Roy Chowdhury was… considered to be a prince among artists…His pattern of life was clearly set, but I could hardly fall into that pattern for I realised that the tenderness in me would not be able to withstand the onslaught of his virile rugged dominance. It was precisely in this context that in Dhanapal I found the nearness and oneness… of two individuals. His linear dexterity… soaked in native richness… gave me the direction I was to take. Yet, I could not turn away from the new introspective spirit of K. C. S. Paniker himself (sic) an accomplished draughtsman and a painter, he never underestimated the need for personal accomplishment and identity, linked with the native genius.’ His works, along with those of other artists associated with the Madras Art Movement, contributed to the emergence of regional modernism in Indian art. |

|

|

|

V. Viswanadhan (1940) V. Viswanadhan is an important artist associated with the Madras Art Movement. He categorically defined his body as a yantra (geometric diagram) with finite limitations. Viswanadhan gained his diploma from the Government College of Arts and Crafts, Madras in 1962. |

|

|

V. Viswanadhan

Untitled

Mixed media on paper, 1972, 19.7 x 25.7 in.

Collection: DAG

V. Viswanadhan

What I Am

Oil on canvas, 1965, 34.0 x 30.0 in.

Collection: DAG

K. C. S. Paniker's works in the late 1950s and 1960s showed increasing abstraction, with figural devices based on Ajanta frescoes and geometricalized fields. Working as a group under Paniker, the painters evolved their work: ‘the painters drew it finer and finer, their drawing turned algebraic, severely notational or calligraphic and well in line with the tradition of indigenous drawing.’ Viswanadhan's abstract paintings were influenced by this environment at the Madras Art School. He, along with other artist-teachers like L. Munuswamy and A.P. Santhanaraj, were responsible for creative and technical explorations within the Madras Art Movement. |

V. Viswanadhan

Collection: DAG

Viswanadhan wrote about the ambivalent nature of his painted surfaces, while linking it to subconscious processes. ‘Here’, he writes, ‘a painting is neither an object, nor a resemblance. It is a non-object, an image that beholds a power, a presence. It does not represent, it does not reproduce. It exists. It is only colour. The form consists essentially of earth, water and fire (light). The real is revealed by the colours as one can see with the masterpieces of humanity such as pre-historic painting, Byzantine icon etc.’ Critics have noted the primitivist thrust in some of Munuswamy’s work as well, which resemble scratched, dimly discernible cave paintings from Lascaux or central India: all a part of their efforts to start over and introduce newness into the world. |

|

The Madras Art Movement was a significant development in the history of modern Indian art, as it marked the emergence of regional modernism. The artists associated with the movement, including Viswanadhan, contributed to establishing another matrix of Indian identity in the post-Independence era through their creative expressions rooted in local traditions and global influences. The movement drew as much from international influences as local, folk and academic ones; but perhaps most of all, from the context of affinities and friendships forged within them, including the differences of opinion that were synthesised over the generations. |

|

|