|

Travel with us Facing the People: Four Public Art Projects from IndiaAnkan Kazi May 01, 2023 Are artworks better consumed in private or in public, with others having equal access to it? How does it matter if artworks are consumed individually or collectively? Public art projects are defined by their accessibility to ordinary people in the streets, making them imaginariums for active citizens in a democracy. The canvases or platforms are constituted by fragments of public infrastructure—such as public buildings, pavements or parks—that are marked by a commitment to the collective spirit of communities and civic welfare. Artists have made site-specific public art in consultation with state or civic bodies since antiquity, drawing artistic work inextricably within the fold of political and social processes of community-making as well. The twentieth century saw many attempts to revive the majesty of public art projects that could encapsulate national difference as well as progressive visions for a polity and give aesthetic form to it. Read on to see how Indian artists—and artists working in Indian spaces—are using this medium today.

|

Image credit: Aravani Art Project and Poornima Sukumar

|

Mexican muralists, Bauhaus and Russian avant-garde artists were central to these visions of public art-making, drawing attention to issues of ecology, infrastructure, social mobility and urban spatiality; along with muralists at Santiniketan such as Nandalal Bose and Benode Behari Mukhopadhyay, who showed that public art does not only thrive at urban centres. Many works have also been either demolished by authorities for various reasons or simply destroyed by natural disasters, making their longevity dependent crucially on the conditions of the place they are sited at. |

|

Oskar Schlemmer, Treppenfresko, 1923, 15 x 6 m., Bauhaus University, Weimar Image credit: Wikimedia commons |

Detail from the Aravani Art Project

Image credit: Aravani Art Project and Poornima Sukumar

Detail from the Aravani Art Project

Image credit: Aravani Art Project and Poornima Sukumar

The Aravani Art ProjectPublic art, especially murals, are often the product of collective art-making. Collaborating with socially marginalized groups to make public art is another method that allows members from minority communities to stake a claim to public space through creative intervention. A muralist from Bengaluru, Poornima Sukumar started the Aravani Art Project in 2016 to create such a platform for the transgender communities in the city. Deriving its name from the mythic son of Arjun who agreed to sacrifice himself after spending a night as a ‘married man’ with a gender-transformed Krishna, the Aravani Art Project centres the transgender community as art-makers and muralists, expecting them to eventually design their own walls. One of their projects was a large mural along a wall of the Dhanvantri Road underpass in central Bengaluru, which was done as a part of the St+Art India street art festival. Titled Naanu Iddiv (‘we exist’), 'it depicts a transgender person using visual motifs that suggest masculine and feminine attributes', drawing from the symbolism of the hibiscus flower, which has both male and female attributes. |

|

Early career artists may use public art, including murals, to showcase the breadth of their talent and vision, while senior artists are motivated by a desire to bypass private collections as the sole context for their art-making. Anonymous artists usually execute radical protest art on walls—such as Banksy’s street art pieces on the separation wall in Palestinian West Bank. |

|

Banksy artwork featuring Mahatma Gandhi in Palestine Image credit: Wikimedia commons |

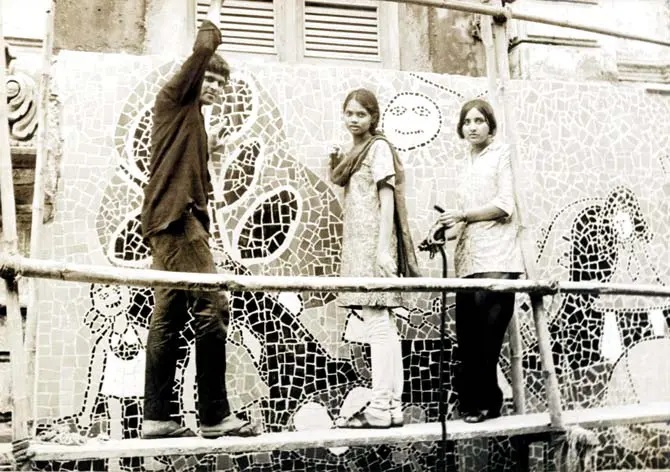

Altaf and Navjot (with Shobha Ghare) working on a mosaic mural.

Image credit: Mid-day

Altaf and Navjot: The public canvasThe artists Altaf (1942—2005) and Navjot (b. 1949) were committed left wing intellectuals and artists who embraced public art in order to share their progressive vision with the masses. In Mumbai, from the years 1972 to 1978, Altaf and Navjot were a part of PROYOM (Progressive Youth Movement), which had links with the radical C. P. I. (M-L) party. Altaf would frequently display his paintings publicly in neighbourhoods like the Matunga Labour Camp and participate in community engagement exercises and readings. Poster-making was a significant strategy, calling for improvised methods and accepting the inevitability of the work’s ephemerality. As Navjot puts it: ‘At that time, I set up a screen printing table in my house. Overnight, we would make 500 text-based posters. We would stick them at railway stations and other public spaces as guerilla girls. We believed that a poster is no less a work of art than the canvas.’ This has also led to a lack of documentary evidence of such displays. In the picture alongside, we can see a glimpse of the artist duo (along with Shobha Ghare) working on a 127-feet long and eight-feet high mosaic mural at the Dawoodbhoy Fazalbhoy High School in the historic Mumbai neighbourhood of Bhendi Bazaar in 1972. Using children’s drawings from a school in Kihim, they used coloured ceramic tiles that were manufactured by Johnson tiles. |

|

Public art can often be subsumed under the effort to ‘beautify’ city spaces—an instinct often described as ‘artwashing’. While many artists are committed to projects of aesthetic improvement and beautification as envisioned by municipal or state authorities, others see it as a euphemism for attempts to gentrify neighbourhood spaces, leading to an escalation of real estate value and displacing original residents eventually. The formation of designated art districts also adds to these concerns. Indian artists like Shanu Lahiri were committed to improving the aesthetic standards of public spaces in cities like Kolkata. However, her famous public statue, Parama, which was lodged at an E. M. Bypass crossing, was summarily removed by state authorities in 2014 ‘by mistake’. |

|

Shanu Lahiri, Parama Image credit: Wikimedia commons |

Narayan Sinha, Capture

Image Credit: The Telegraph

'Capture' at the Nandan Film ComplexNarayan Sinha’s Capture is an installation at the Nandan film complex in Kolkata. It is a government-run film and cultural centre that was inaugurated in 1985 by Satyajit Ray, who also designed its iconic logo. Sinha’s installation brings the great Bengali filmmaker’s mythic presence (as a ‘Renaissance man’) into the work as well, with its melding of the figures of a writer, a cameraman and a film director that have their eyes directed towards the potential audience that queues up outside the main auditorium before each screening. The installation was built from discarded scrap material, with the ‘broken parts of a projector (being used) to design the cameraman’, and parts of an old typewriter to design the body of the writer-figure. Abandoned drainage pipes were employed to construct the heads of the figures, almost resembling periscopes and suggesting the reception of vision to be an embodied process, both subjective and culturally grounded. As a significant cultural centre for Kolkata’s film-loving public, the installation is an ode to this spirit of film-watching while acknowledging the diverse influences that have shaped cinematic authorship over the last century. |

|

Kamayani Sharma on Kolkata’s subversive political graffiti, visible between 1960 and 1990: ‘It was a multi-layered and textured conversation between the frequently anonymous artist, the public and the constructed environment. Ranging from drawings of Naxalite party workers killed by the police sketched using pieces of charcoal taken from their funeral pyres to Portraits of Indira Gandhi in psychedelic colours, these images were subversive, irreverent, socially aware and gave vent to a deeply felt resentment and anger against the establishment.’ What kind of materials were traditionally used? Swapan Ghosh, a prolific graffiti artist and wall writer for the Communist Party of India (Marxist), says, ‘In the old days we would make posters with alta [the red liquid used by Bengali women to decorate their feet] and ink on newspapers.’ |

|

Image credit: Wikimedia commons |

Nagji Patel, with his work The Banyan Trees in the background

Image credit: The Times of India

The Kirti Torana at Vadnagar

Image Credit: wikimedia commons

'The Banyan Trees' by Nagji PatelNagji Patel (1937-2017) was one of the most iconic public artists of India, who worked primarily with marble and stone outdoor sculptures. In 1991, he installed The Banyan Trees, a twenty-feet high (20’ x 16’ x 5’) set of columns that evoked the form of banyan tree roots and served as a gateway to the city of Baroda (now Vadodara). The banyan tree is vad in Gujarati, from which the city’s modern name Vadodara derives, making the work evocative of the city’s history too. It was commissioned by the Indian Petrochemicals Corporation Ltd. and stood at the Fatehgunj crossing. It was made out of carved Jodhpur pink sandstone, with the striations suggesting the famous roots, and it changed hues according to the weather—reflecting a ‘live’ disposition. The pillar also claims affinities with the many toranas that can be found across Gujarat today, especially the set of 12th century Kirti Toran columns at Vadnagar, which may have inspired its construction. A mix of ecology, urban intervention and the ancient civilizational imagination at work, the installation was removed due to an impending overbridge construction—an eventuality that was self-reflexively documented by Chinmoyi Patel in her film The Solid Melts into Sauce. |

|

Aside from governmental bodies, corporate funding and institutional grants are other regular sources for sponsoring public art projects today. Public art across history also tells us a lot about the major patrons of art in a particular region, whether they were private individuals and corporate bodies, or civic authorities in an influential municipality. Moreover, as artists like Anjolie Ela Menon have suggested, late-career artists also seek the opportunity for doing public art for another valuable reason, the desire to have their work seen regularly: 'Painting is arduous work and in the active, creative years that remain I’d rather do works for public spaces. So much of my output has disappeared into private collections that I would like to remedy that if possible. Railway stations, airports, hotels, public buildings—these are the great patrons of the future, as temples, churches and palaces were in the past.' |

|

Detail from Anjolie Ela Menon's Delhi Airport mural Image credit: Hindustan Times |