|

On Collecting Four Famous Collectors who shaped Indian art historyAnkan Kazi and Shreeja Sen March 01, 2023 How did the idea of Indian art come to be constructed over the last century and more? The painstaking work of collectors and curators went a long way towards establishing the history of art in India. In this article we highlight some of the most significant collectors of art from South Asia over the course of the twentieth century. Usually starting as personal collections, most of them would eventually donate their works to museums in India or abroad, allowing these rare works to be seen regularly by new generations of art enthusiasts across the world. Their collections, curated exhibitions and publications fashioned the canons of Indian modern and pre-modern art |

Stella Kramrisch. Image courtesy: Stella Kramrisch Papers, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Library and Archives

|

'We are peculiar people. I say this with reference to the fact that whereas almost all other peoples have called their theory of art or expression a 'rhetoric' and have thought of art as a kind of knowledge, we have invented an 'aesthetic' and think of art as a kind of feeling.' -A. K. Coomaraswamy, 'A Figure of Speech or a Figure of Thought?' |

|

A. K. Coomaraswamy Yaksas Image courtesy: archive.org |

A. K. Coomaraswamy

Image courtesy: wikimedia commons

A. K. CoomaraswamyAnanda K. Coomaraswamy (1877-1947) was one of the most influential historians, collectors and theorists of South Asian art, especially pertaining to India, Sri Lanka and Pakistan. Trained as a geologist, he advocated for subjective methods of knowing and collecting artistic heritage, which he developed through a critique of the colonial-archaeological methods of studying art. By the 1900s he had started his personal collection of art, which included paintings, drawings, objects and sculptures. He collected for public institutions and exhibitions as well, such as the United Provinces Exhibition at Allahabad (now Prayagraj) in 1910. He offered his own collection to set up a national museum in India, but it was not taken up. Eventually, he left for the United States of America, becoming the first Keeper of Indian art at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) in 1917 after selling most of his collection to Denman Waldo Ross, a benefactor of the MFA. |

Utka Nayika, late eighteenth century. Opaque watercolor on paper, sheet: 9 13/16 x 7 9/16 in., Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Dr. Ananda K. Coomaraswamy. Image courtesy: Brooklyn Museum

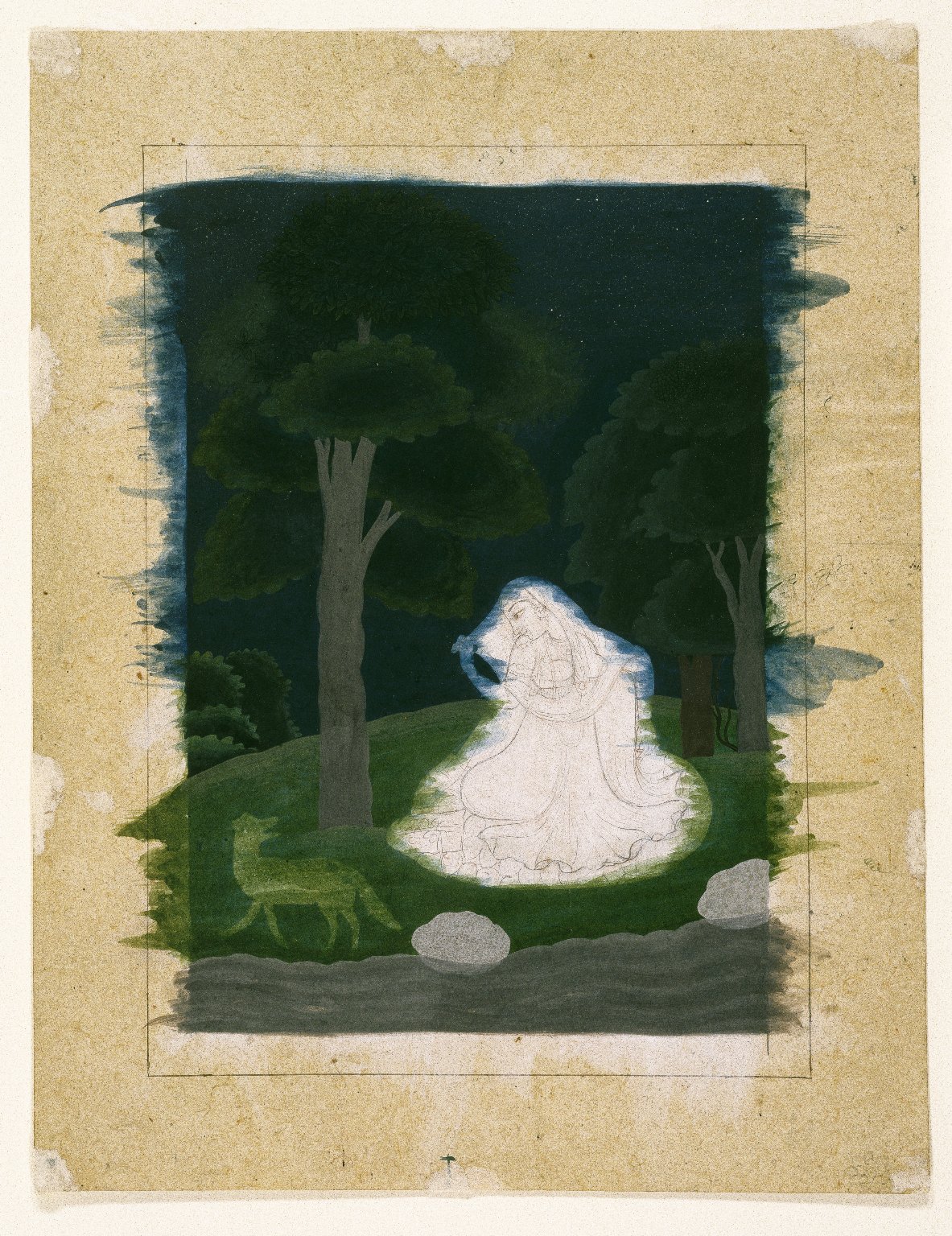

Large First Drawing for a Miniature Painting, late eighteenth century, Brush and charcoal, 12 1/2 x 9 5/8 in. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Dr. Ananda K. Coomaraswamy. Image courtesy: Brooklyn Museum

Portrait of Raja Sansar Chand of Kangra, ca. 1800-1810. Opaque watercolor and gold on paper, sheet: 8 3/4 x 7 1/4 in. (22.2 x 18.4 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Dr. Ananda K. Coomaraswamy. Image courtesy: Brooklyn Museum

Working as a curator at the museum, he wrote catalogue descriptions and scholarly publications on Indian art and sculpture—making his collection possibly the most significant one in the understanding of Indian art globally. His definitive Catalogue of the Indian Collections in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston was published in five volumes from 1923 to 1930. Described as '(o)ne of the oldest and most encyclopedic collections of Indian art in the United States', the Boston MFA’s collection of early Buddhist sculptures, Mughal and Rajput miniature paintings and archaeological artefacts—such as those he helped collect at Chanhu Daro in the late 1930s—was largely built by Coomaraswamy. He also gifted works to other museums, such as the Brooklyn Museum. A collection of his voluminous publications is also held by the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts (IGNCA) |

|

‘[Rabindranath Tagore] asked for bottles of coloured ink, and, when these arrived, there began to emerge a series of paintings and sketches.’ -Leonard Elmhirst (The Dartington Hall Trust Archives) |

|

|

Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941), Untitled (Figure in Yellow), Mixed media on paper laid on card, 1938 24.7 x 17.2 in.

Collection: DAG

Leonard Elmhirst (left) with Rabindranath Tagore (center)

Image courtesy: The Dartington Hall Trust archive

Leonard ElmhirstLeonard Elmhirst (1893-1974) was an educationist and agricultural scientist who worked closely with Rabindranath Tagore on his rural re-development projects at Surul, near his newly established educational institute at Santiniketan. This would plant the seed for the Rural Reconstruction Department at Sriniketan. Tagore met Elmhirst when he was in New York in 1920 and invited him to work together, beginning a lifelong friendship. Elmhirst would also accompany the poet on his travels to China, Japan and Argentina. Eventually, he left for Britain to start his own alternative rural cooperative at Dartington Hall in South Devon under the advice and approval of Tagore. Elmhirst would describe it as 'not unlike a mingling of Santiniketan and Sriniketan'. Tagore is known to have gifted seventeen (in some accounts, twelve) of his own works to the Dartington Trust and made several sketches and paintings while he was visiting the estates in 1930—possibly gifting some of these to the Elmhirst children, William and Ruth. These formed a significant archive of Tagore’s paintings in Europe until the 2000s when most of them were auctioned off, bringing newfound value to the poet’s artistic works as well. |

|

‘(My) first meeting (with Rai Krishna Dasa, ‘doyen of Indian collectors’) was in Patna in March 1942 when as a young member of the Indian Civil Service and local District Magistrate, I presided at a Hindi lecture on Pahari painting which he gave in Patna University. We became friends and I stayed with him at Banaras on four occasions between then and 1948, feeling only too happy to escape from the officialdom of Bihar…What students of Italian painting may have gained from visits to I Tatti, I gained from visits to Sita Nivas.’ - W. G. Archer, Indian Paintings from the Punjab Hills |

|

|

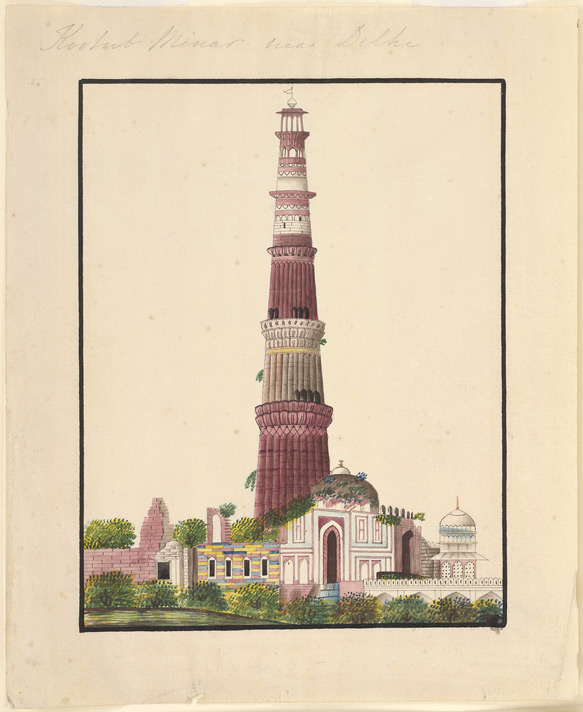

Drawing of the Qutb Minar in Delhi, by a Delhi artist, c.1830-35, 22 x 28 cm., watercolour, from the collection of Mildred and W.G. Archer. Inscribed on the front: 'Kootub Minar near Delhi'. Image courtesy: British Library Board, Shelfmark: Add.Or.4034, Item number: 4034.

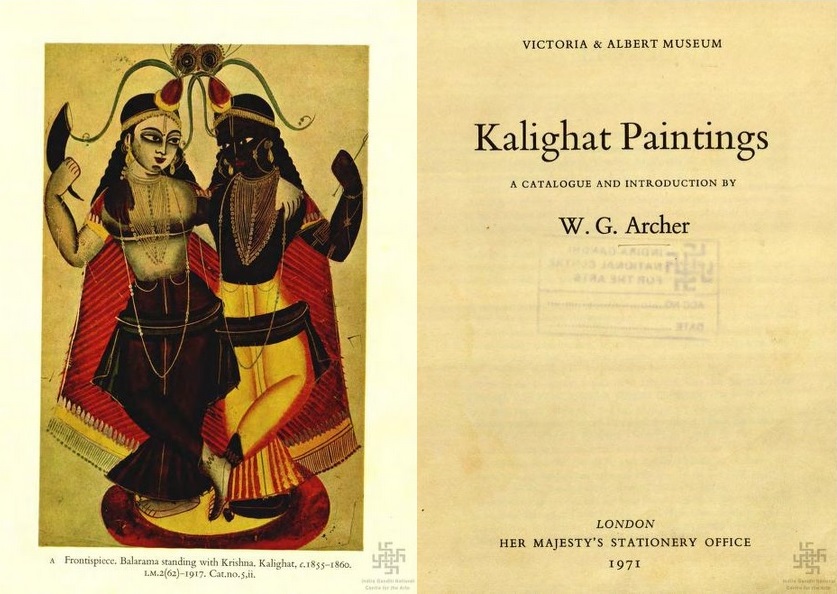

W. G. ArcherWilliam G. Archer (1907-1979) worked as a British civil servant in India, during which time he also collected and wrote about the artistic heritage of the subcontinent, focusing on and creating a global taste for Kalighat paintings, miniature paintings from Rajasthan, Punjab and Kangra, Indian modern art as well as folk and tribal traditions of art among others. Following Indian Independence in 1947 and his retirement in England, he served as the Keeper of the Indian Section at the Victoria and Albert Museum from 1949 to 1959. In his writings he tried to make formal or theoretical connections across different categories of art that he collected or was inspired by. For instance, he collected Mithila paintings and wrote about its affinities with the modern works of Joan Miro and Pablo Picasso. His wife, Mildred Archer, was a major art historian of Company and miniature paintings and some of her books, like Indian Popular Painting in the India Office Library (1977), contain large samples of the works collected by the couple in India. |

Title page of Kalighat Paintings by W. G. Archer. Image courtesy: archive.org

Archer's books frequently carried catalogues that mentioned names of Indian collectors, making them a valuable resource for provenance researchers and art historians

Archer’s life and career is a gateway towards discovering a network of Indian art collectors who were active at the time and were his friends—such as Gopi Krishna Kanoria, who held a major collection of Indian miniatures at Patna, and Rai Krishna Dasa, founder of the art museum at Banaras Hindu University and the Bharat Kala Bhavan. In their monographs, both William and Mildred Archer frequently name other collectors whose practices inspired their own and who provided information about works they collected. Writing about one such collector, Professor Ishwari Prasad, Mildred Archer notes, “…it is largely through his memory of his grandfather and great-uncle and the stories repeated by them that the oral tradition has survived. Moreover, a number of existing paintings owe their preservation to his family collection, and much accurate attribution of particular paintings has proved possible through his precise recollections.” From his own writings and those of others like Stuart Cary Welch, it is clear that Archer maintained a great collection of artworks at his home as well that included 'tribal woodcarvings, miniatures and contemporary paintings' that were accessible to visiting friends and scholars. |

|

‘I arrived there just a little before midnight. It was beautifully calm… It was the day of the Santiniketan mela, the founding day, so there was a beautiful fair where the villagers came and displayed their handmade goods. I fell in love, first of all, with a toy wooden cart, a ratha, and also with one painting, a sketch of that bare landscape by one of the pupils of Nandalal Bose., who was the principal of Kala Bhavan. That painting, however, was priced at ten rupees and I couldn’t afford that because I had seven rupees left, so I spoke to Nandalal Bose and said, ‘I’m anxious to get it.’ He said, ‘Alright, he’ll give it to you for seven rupees.’ These were my last seven rupees. I had nothing else. This was my first day in Santiniketan.’ -Stella Kramrisch, from Exploring India's Sacred Art: Selected Writings of Stella Kramrisch |

|

|

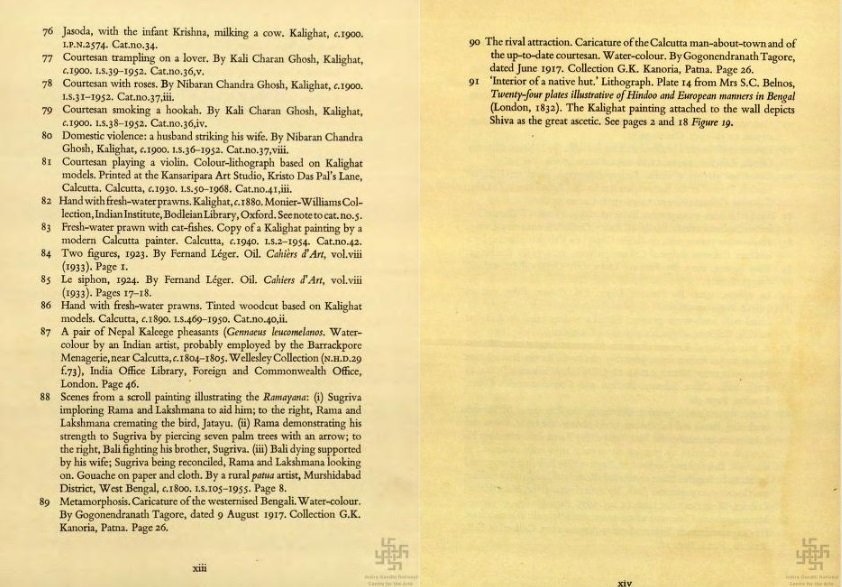

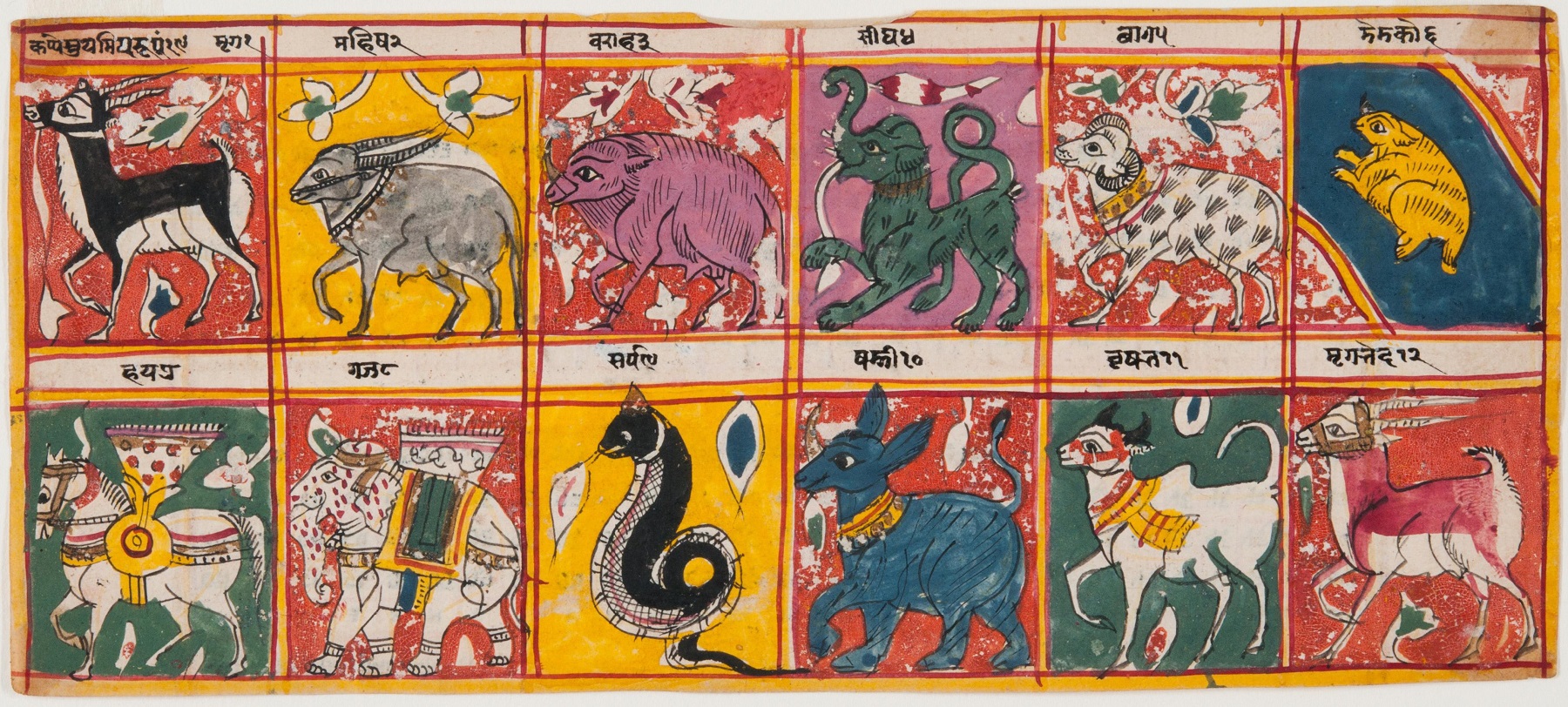

Artist unknown, 12 Zodiac Signs, Page from a dispersed series of the Sangrahanisutra, seventeenth century

Opaque watercolor, gold, and ink on paper, Sheet: 4 1/4 × 9 3/4 in., Stella Kramrisch Collection, 1994. Image Courtesy: Philadelphia Museum of Art, Library and Archives

Artist unknown, 12 Zodiac Signs, Page from a dispersed series of the Sangrahanisutra, seventeenth century

Opaque watercolor, gold, and ink on paper, Sheet: 4 1/4 × 9 3/4 in., Stella Kramrisch Collection, 1994. Image Courtesy: Philadelphia Museum of Art, Library and Archives

Stella KramrischStella Kramrisch (1896-1993), was a curator, critic, and art-historian specialising in Indian art. While teaching Indian Art at Oxford University post World War I, she met Rabindranath Tagore who invited her to teach at Visva Bharati University in Santiniketan. Kramrisch taught there from 1921 and started collecting the local folk arts which included scrolls and textiles. In 1923, Kramrisch began teaching at the University of Calcutta, where she advised her student Devaprasad Ghosh on the organisation of university students to collect examples of ‘folk art’ from the villages around Calcutta (now Kolkata) which eventually formed the collection at Sir Asutosh Mukherjee Museum in the University. Similarities between the pieces in this museum and Kramrisch’s personal collection suggests that this effort also helped her add to her own collection. Kramrisch travelled extensively across India for her research and amassed a collection of temple sculptures unrivalled by any collection outside of India. In 1931, she sent most of her collection on long-term loan to England, mainly to the Victoria and Albert Museum. |

Artist Unknown, A Lady Consoled By Her Confidante, Page from a dispersed series of the Rasikapriya, c. 1785

Opaque watercolor on paper, Sheet: 10 × 7 1/8 in., Stella Kramrisch Collection, 1994. Image Courtesy: Philadelphia Museum of Art, Library and Archives

In 1950, Kramrisch moved to Philadelphia and joined the faculty at the University of Pennsylvania. Soon after, her personal collection of Indian temple sculpture went on display at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, where in 1954 she became the first curator of Indian art. In 1956, she facilitated the sale of her personal collection to the Museum and installed the museum’s first South Asian art gallery. Kramrisch continued to collect throughout her life and at the time of her death in 1993, her bequest to the Philadelphia Museum of Art included over 700 objects. Her personal collection has formed the basis for more than twenty thematic exhibitions, including landmark exhibitions like Unknown India, curated with artist Haku Shah, Manifestations of Shiva, and Kantha: The Embroidered Quilts of Bengal from the Jill and Sheldon Bonovitz and the Stella Kramrisch Collections . |

|

According to Ernest Hemingway, Gertrude Stein once said that, ‘You can either buy clothes or buy pictures. It's that simple. No one who is not very rich can do both. Pay no attention to your clothes and no attention at all to the mode, and buy your clothes for comfort and durability, and you will have the clothes money to buy pictures.’ Having a friend like Pablo Picasso, who also made a portrait of her, perhaps made it easier for her to dissolve the boundaries between buying everyday commodities like clothes, and art. Increasingly over the twentieth century, however, modernist artists (Stein included) emphasised the proximity between everyday objects and sanctified works of ‘high’ art—constantly pushing one domain to absorb the contents of the other. If art has been democratised to a large extent through such experimental practices, art collecting has also called for imaginative interventions into deciding what should be collected, from where and how they must be collected. It is difficult to imagine this today, but the collectors who are featured here worked in an environment when the familiar canons of Indian art did not exist, even though actual artworks were widely available. Through their public and personal work, which included making connections with other collectors as well, they added some of the crucial building blocks for an Indian art history today—going right back to ancient Indian art. |

|

|