Following the cat in Indian Art: Reading B. N. Goswamy

Following the cat in Indian Art: Reading B. N. Goswamy

Following the cat in Indian Art: Reading B. N. Goswamy

Jamini Roy, Untitled (detail), Tempera on cardboard. Collection: DAG

Billi boli meow, kahe ghabrao, main toh chali Kashi, gale mil jao (‘The cat said meow, don't worry, I'm just going to Kashi, come, give me a hug)’, runs the lyrics of a ‘50s Bollywood song sung by Lata Mangeshkar and Manna Dey, quoted in the art historian B. N. Goswamy’s book titled The Indian Cat, which would be his final publication before his demise last year (2023). How did he map the teasingly complex relationship between cats and humans—as it has unfolded over the years in artworks?

|

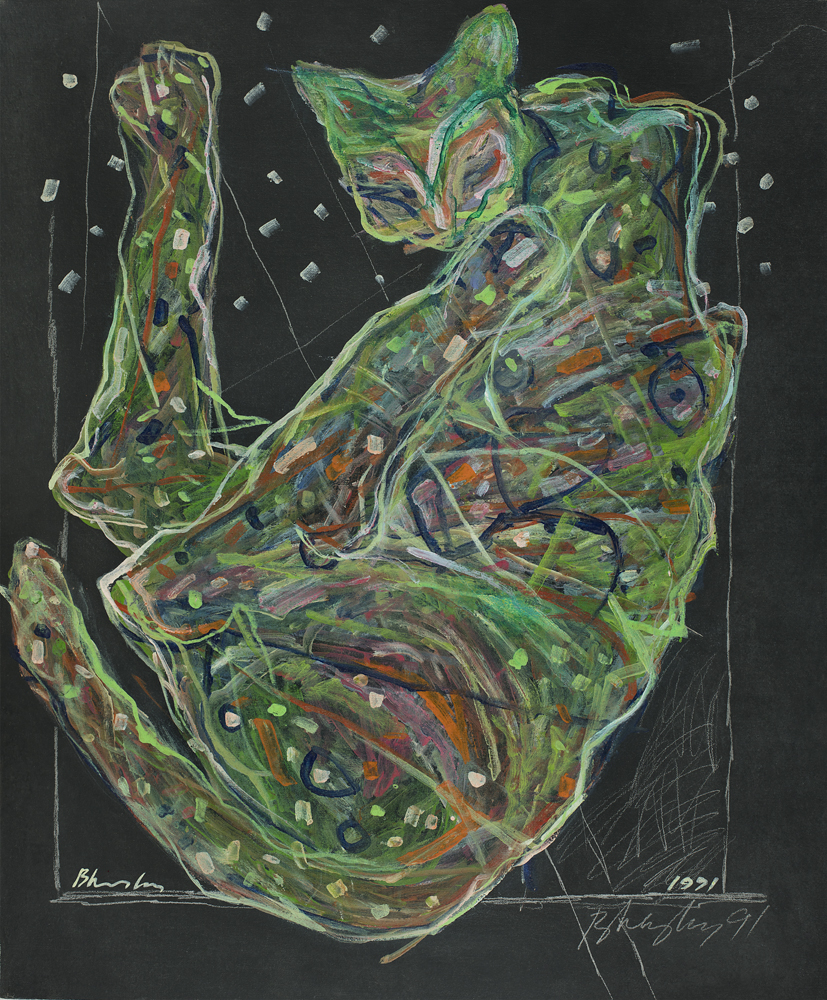

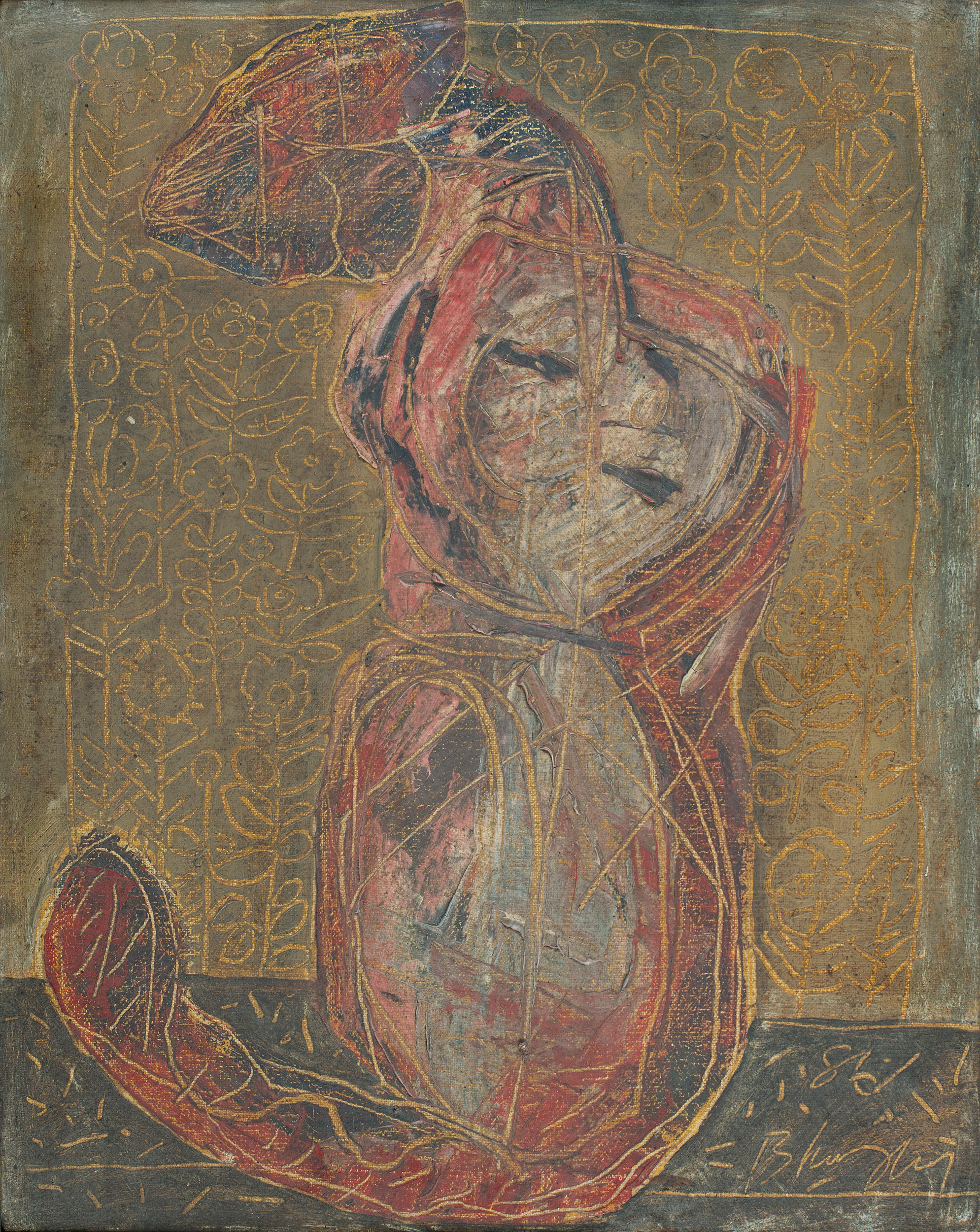

R. B. Bhaskaran, Untitled, 1991, Acrylic and glass marker on canvas, 27.7 X 23.2 in. Collection: DAG |

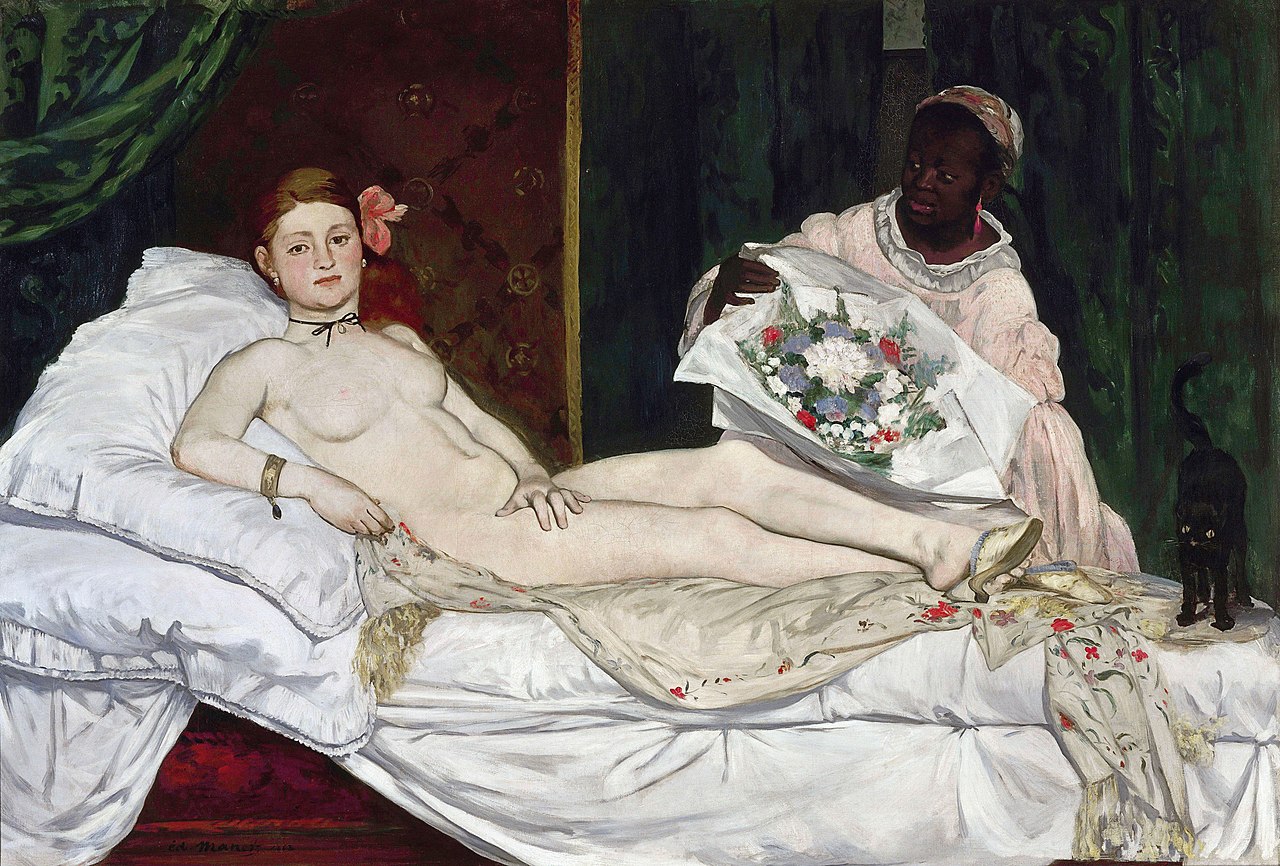

Cats have always been an artistic preoccupation in allegorical and literal iterations, be it Edouard Manet’s sketches of the creatures engaged in ordinary, everyday acts, the black tabby on Olympia’s bed which has possible sexual connotations or Pablo Picasso’s cat devouring a bird—which refers to occupied Spain. The commonly held reputation by felines of being cunning is highlighted by Goswami through popularly circulated fables and moral narratives. Tales of the thieving cat has been retold in allegorical stories across early modern Indian art, particularly in Mughal miniatures—which Goswami mainly focuses on, and also in Kalighat pats.

Edouard Manet, Olympia. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

A stolen fish or prawn in their mouths, the cats in Kalighat pats represent religious avarice. This pseudo-religious cat is also seen in Mughal miniatures, as Goswamy locates her capturing a partridge and a quail who had come seeking advice from the holy being. Hemen Mazumdar creates a cheeky interaction between the popular art of Kalighat pats—identifiable by the iconography of the painted image—and the supposed ‘high art’ of painting a lobster in oils, in his untitled work. Here, a group of cats seem to have upset an artist’s painting of lobsters, in an attempt to eat them. Is he trying to highlight the reality effect of academic painting, proudly proclaiming his own talents in illusionism?

Hemen Mazumdar, Untitled (A Dry Feast), Watercolour on paper pasted on board, 15.5 x 22.7 in. Collection: DAG

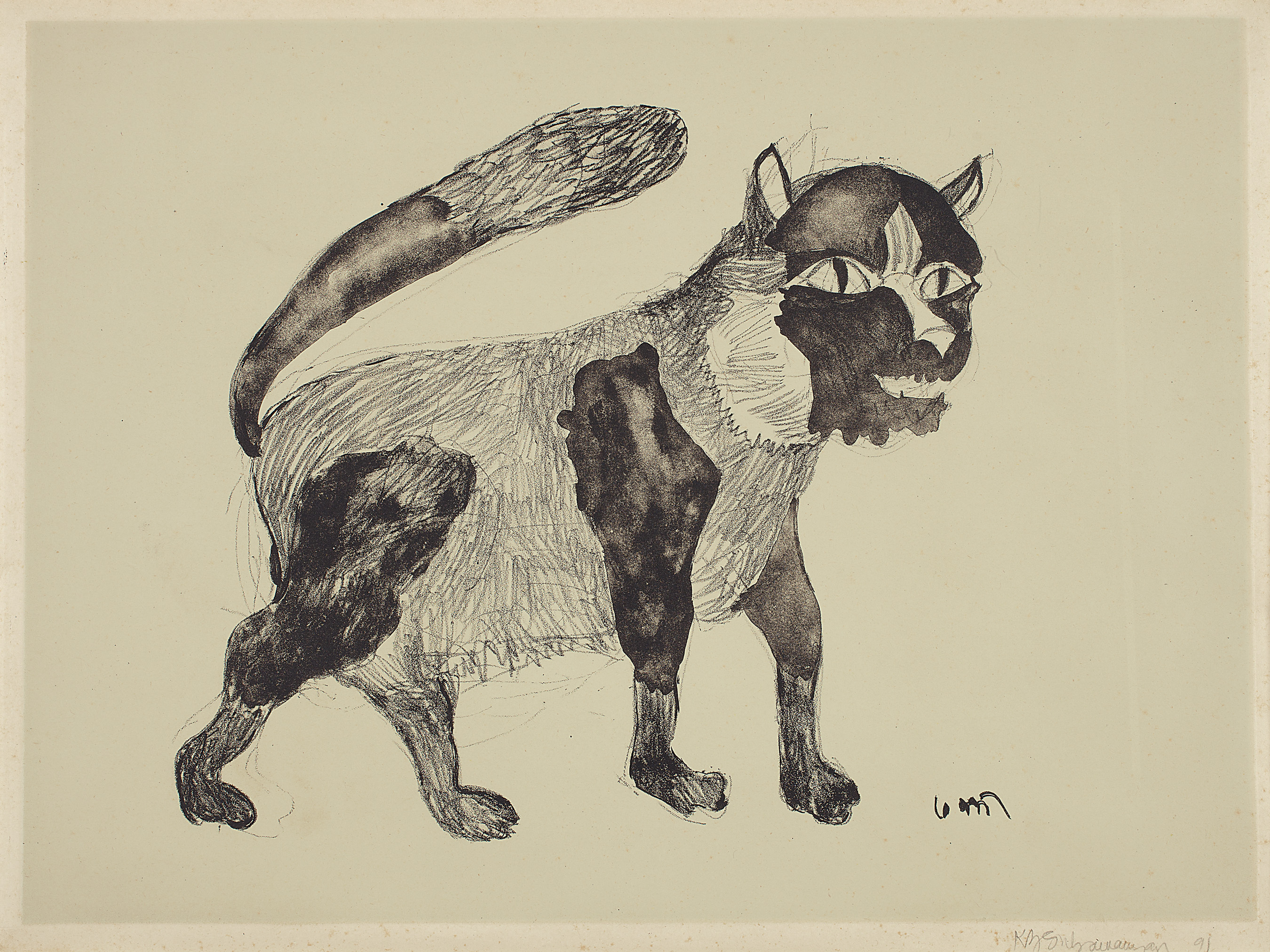

Humorous secular renditions of this cat have been painted by K. G. Subramanyan too, whose grey feline exudes a sense of mischief. Goswamy chooses a male cat in a bazaar, stealing a fish from a hawker’s basket. Subramanyan’s cats co-exist with humans, but also retreat into a private world where they gnarl at each other over fish loot, rendered in sharp strokes, heightening the tension.

K. G. Subramanyan, Untitled (Cat), 1991, Lithograph on paper, 11.7 X 15.7 in. Collection: DAG

Jyoti Bhatt’s cat snarls at the viewer, its mask-like face giving it eerily human attributes. Bhatt has painted half-feline and half-human cats, like in an etching titled ‘Dilli ki Billi’ (The Cat from Delhi). Interestingly, that cat has a massive swastika etched on her body. This cat has already ingested a parrot, which does not look dead, yet.

Jyoti Bhatt, Cat with a Parrot in her Tummy, 1964, Ink and watercolour on paper, 13.7 X 19.5 in. Collection: DAG

However, it wouldn’t be fair to merely highlight feline pilfering as Goswami draws our affectionate attention towards the cat companion, a recurrent accompanying figure in Indian art. The same Kalighat cat is transformed into a nurturer by Jamini Roy, as instead of a fish, a mother cat carries her baby in her mouth. In some miniatures from the Ragmala series, cats become the quiet companions of the nayika, suffering the pangs of the heart, as she waits for her lover. Sometimes, they are also a metaphor for the lover, as their lithe bodies steal the nayika’s parrot and flee—with the parrot symbolising the heart. ‘The princess…wields a cane but seems to be posing rather than attacking the cat,’ writes Goswamy. The sensual association of the cat is ever present, like in a nineteenth century painting from Rajasthan where a cat nestles against their mistress’ breast like a lover, which Goswamy points out in an unsettlingly masculine manner.

|

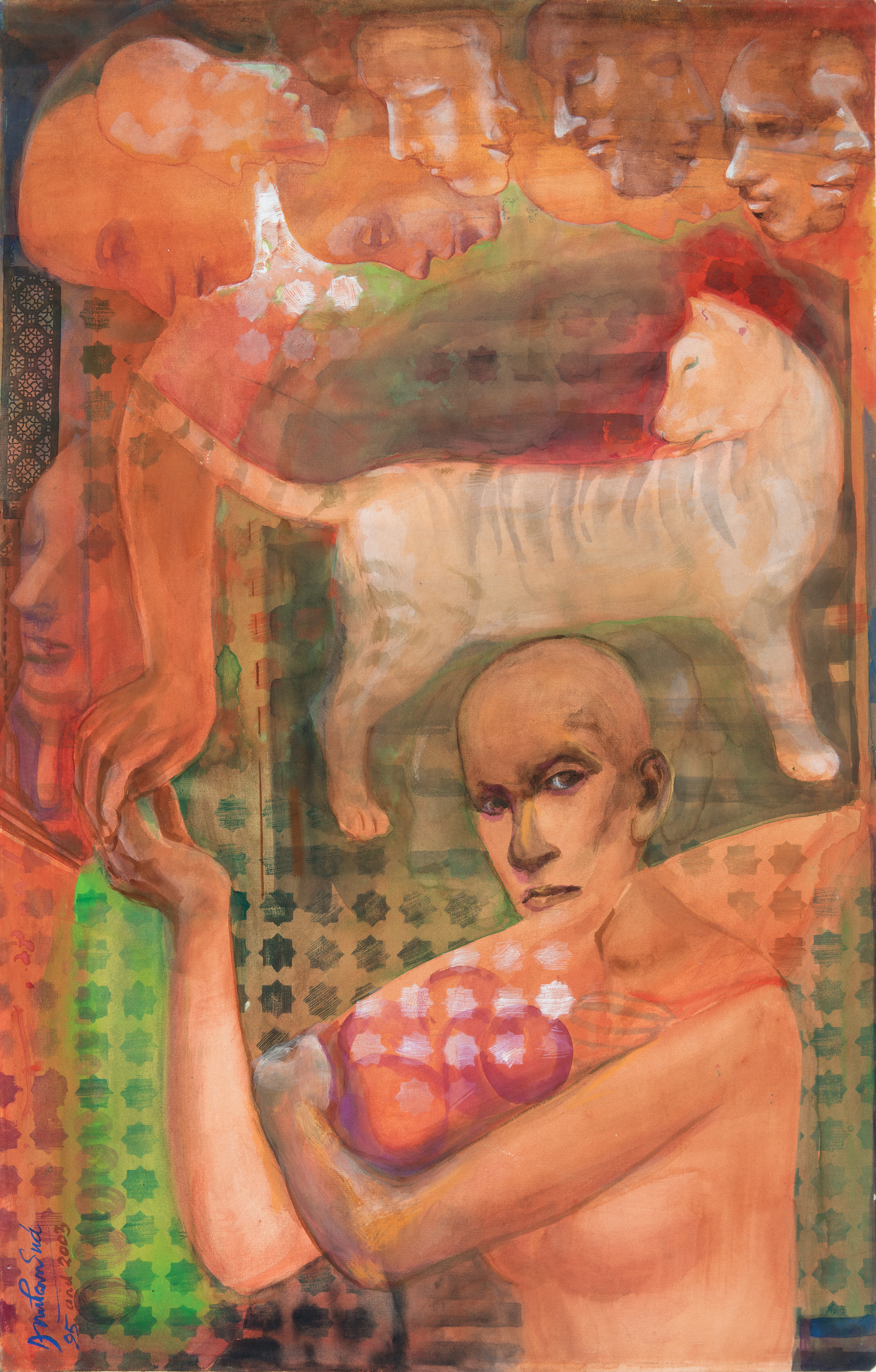

Anupam Sud, Cat Has Seven Lives, 1995-2003, Watercolour and gouache on paper, 39.0 X 25.2 in. Collection: DAG |

The relationship between cats and modern art may not have been explored at length in Goswamy’s book but the associations are there for us to notice. Some of the very forms of modern urban life have been communicated to us as cat-like movements, most famously in T. S. Eliot’s poem The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock:

'The yellow fog that rubs its back upon the window-panes,

The yellow smoke that rubs its muzzle on the window-panes,

Licked its tongue into the corners of the evening,

Lingered upon the pools that stand in drains,

Let fall upon its back the soot that falls from chimneys,

Slipped by the terrace, made a sudden leap,

And seeing that it was a soft October night,

Curled once about the house, and fell asleep.'

The languor and ennui of modernity forms the subject of much feline-inspired art.

|

R. B. Bhaskaran, Untitled, 1986, Oil on canvas, 15.0 x 12.0 in. Collection: DAG |

Cats become playmates and fierce watchers in Anjolie Ela Menon’s works. In a work titled Nude with Cat they exude masculine protectiveness standing on either side of a nude woman, while their frisky whimsicality amuses her. Menon herself has a cat and many others like Ramkinkar Baij and Gopal Ghose were surrounded by their furry co-inhabitants, who wriggled their way into their sketches. ‘Most revealing of all are Ramkinkar’s many sketches of cats and kittens,’ writes Trisha Gupta. ‘Unlike any of his other animals,’ she goes on to note, ‘they have personalities. In one famous image called Artist and his Models (Kittens), a lithograph from 1968, several large, unruly kittens with big expressive faces play a game of rough-and-tumble, dwarfing the artist, a rather crazed-looking black figure without a face. They have exaggerated facial expressions, almost like the anthropomorphic features of cartoon animals. They seem, in other words, like pets.’

Among the few modern works mentioned by Goswamy is a patachitra by Bapi Chitrakar from Pingla in Bengal. Painted in the style of the usual babu and bibi patachitra, it marks the absence of the babu or client seeking sexual favours and replaces him with the courtesan’s cat. As the mistress looks at it lovingly, Goswamy captions the cat as saying, ‘At least I’m here bau’di (sister-in-law), no?’ which has multiple layers of meaning, ranging from playful to amorous. Empathy and friendship do not stop the cats from having scathing opinions, however, and in one painting where a courtesan has become the king’s favourite, the cat seems to be mocking their mistress pretending to be the queen, dressed in finery.

While feminine relationships with cats seem to mostly harp on friendship or the sexual, Goswami seems to have chosen works where men and cats seem to be primarily distant, in the same space. When sitting beside Sufi saints, who are almost always engrossed in reading, they are left to their own devices—one of them had even tied the cat up in a corner. In another Mughal miniature, two princes fight violently over a cat. One of the interesting paintings that Goswami highlights, is almost an exact copy of a Dutch print titled ‘Dolor’ or melancholy—except here, the man sits in his garden instead of indoors, but what’s constant is a cupboard in which a jug of milk lies upturned, as a cat laps it up, its master lost in thoughts. The presence of a feline with strange starry patterns seems to have been painted to highlight the dandiness of a European man in a Mughal folio—the only man who shows some signs of feline ownership. ‘Obviously, his pet spotted cat, craning her neck and looking up at him, is expecting to either talk to him, or to be petted,’ writes Goswamy.

Jamini Roy, Untitled (Cats), Tempera on board, 15.7 X 15.7 in. Collection: DAG

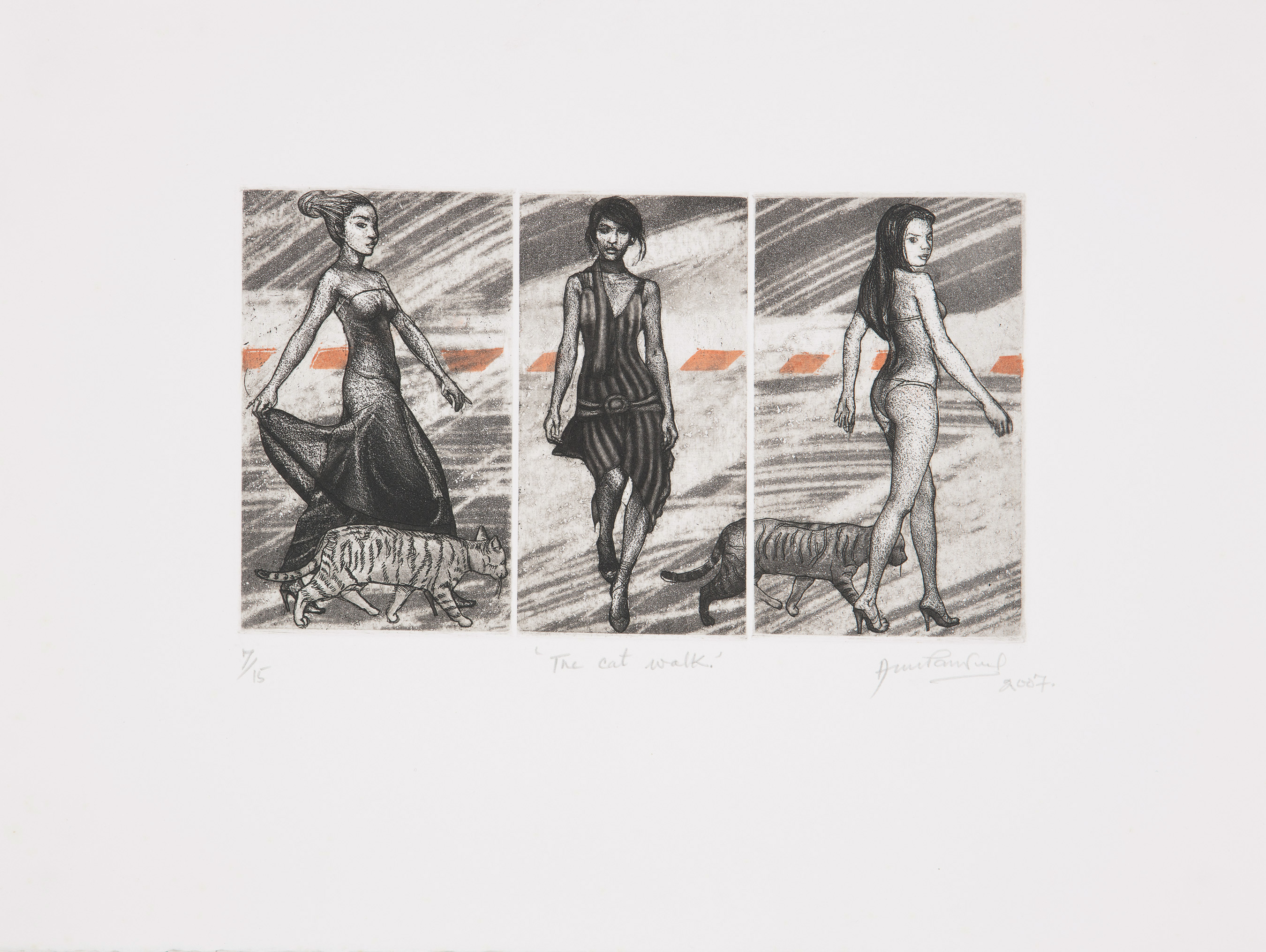

Sometimes, they remain indifferent to the happenings around them, as depicted in the Freer Ramayana where amidst the sorrow of Ram's exile, they prance about unconcerned. Goswami seems to suggest they are above such temporal matters. In Anupam Sud's artwork, cats strut alongside models on the runway, almost as if instructing them on the art of the catwalk. From the premodern era to our own, then, cats have accompanied human presence—riffing of their own symbolic meanings in such relationships. Unlike dogs, faithlessness is a recurring theme, recalling Eunice De Souza’s poem Advice to Women:

Keep cats

if you want to learn to cope with

the otherness of lovers…

Otherness is not always neglect –

Cats return to their litter trays

when they need to.’

Their ‘otherness’ seals a mysterious pact between their human ‘owners’, the significance of a suggestive artwork and the nature of relationships. Unlike Goswami's usual scholarly works, this book is a playful exploration of feline presence in Indian art, catering to the everyday reader who delights in the charm (and threat) of cats.

Anupam Sud, The Cat Walk, 2007, Intaglio on paper, 6.0 X 9.2 in. Collection: DAG