Finding Kali: Artistic traditions from North India and RajasthanThe Editorial Team March 01, 2024 Depictions of the goddess Kali in Bengal art are probably more ubiquitous in the national imagination than those from other parts of India. It is important to recognise, however, that the goddess was frequently painted in works that date from much earlier than the famous Bengal artworks on Kali. Miniature traditions in the north, especially Pahari paintings, and Rajasthan were active centers for producing such imagery, which DAG’s exhibition on the goddess seeks to include. Other highlights from the show include rare reverse glass paintings on the goddess and ceramic works. |

|

In Himachal Pradesh, Kali is also venerated, though with regional variations in her portrayal. Given the mountainous terrain and the cultural influences of the region, Kali's depiction might incorporate elements of local beliefs and practices. In some cases, Kali may be depicted in a more serene and less aggressive manner compared to some other depictions. She might be shown as a benevolent mother figure, protecting her devotees from harm and evil forces while still embodying the power of destruction. These artistic representations also tend to highlight Kali's role in protecting the natural environment and ensuring the well-being of the community. |

|

|

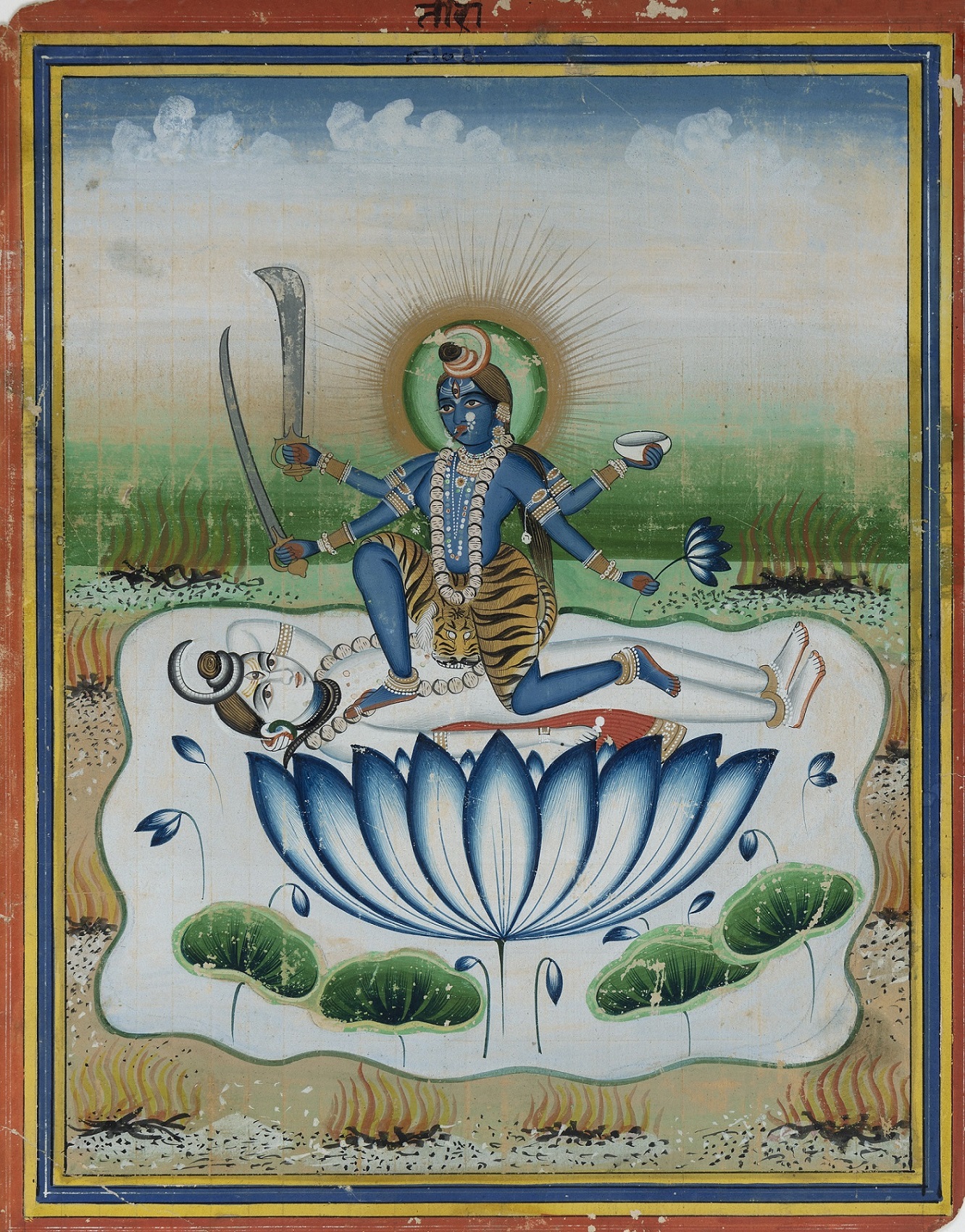

Unidentified Artist (Miniature Painting)

Tara

Natural pigment highlighted with gold and silver pigment on paper, 10.0 × 8.0 in.

Collection: DAG

As the curator of the exhibition Gayatri Sinha points out while discussing the Bengali tradition, ‘This is a complete reversal from the hitherto painted contemporary depictions of Kali in Pahari miniatures as gaunt and hideous, with sagging breasts, an emaciated body, and a tiger skin to cover her nakedness. This description follows that of the Devi Bhagavata Purana (ninth to fourteenth century) that celebrates the Devi or the great goddess as the primary cosmic power. Kali, embattled in the paintings of Guler, Mandi and other hill schools of the seventeenth century, appears to aid Durga in her fight against the asuras Chanda, Munda and Raktabeej. Alternatively, she is depicted as beautiful, as she stands on a prone Shiva, in a delicately rendered cremation ground, as in Kangra painting.’ Landscape is another major protagonist in these works, drawn from the hilly regions where they were made and referring back to them as part of a sacred geography. |

|

Her sexualised form, the specifics of her relationship with Shiva, were Bengali interpretations of the icon. Although it is worth pointing out that the Pahari paintings are not bereft of erotic content altogether. Contrasting with the passive and supine images of Shiva in the Bengali tradition, in some of the Pahari works Shiva, even as he is being trampled upon by the goddess, sports a tumescent penis—suggesting sexual excitement. |

|

|

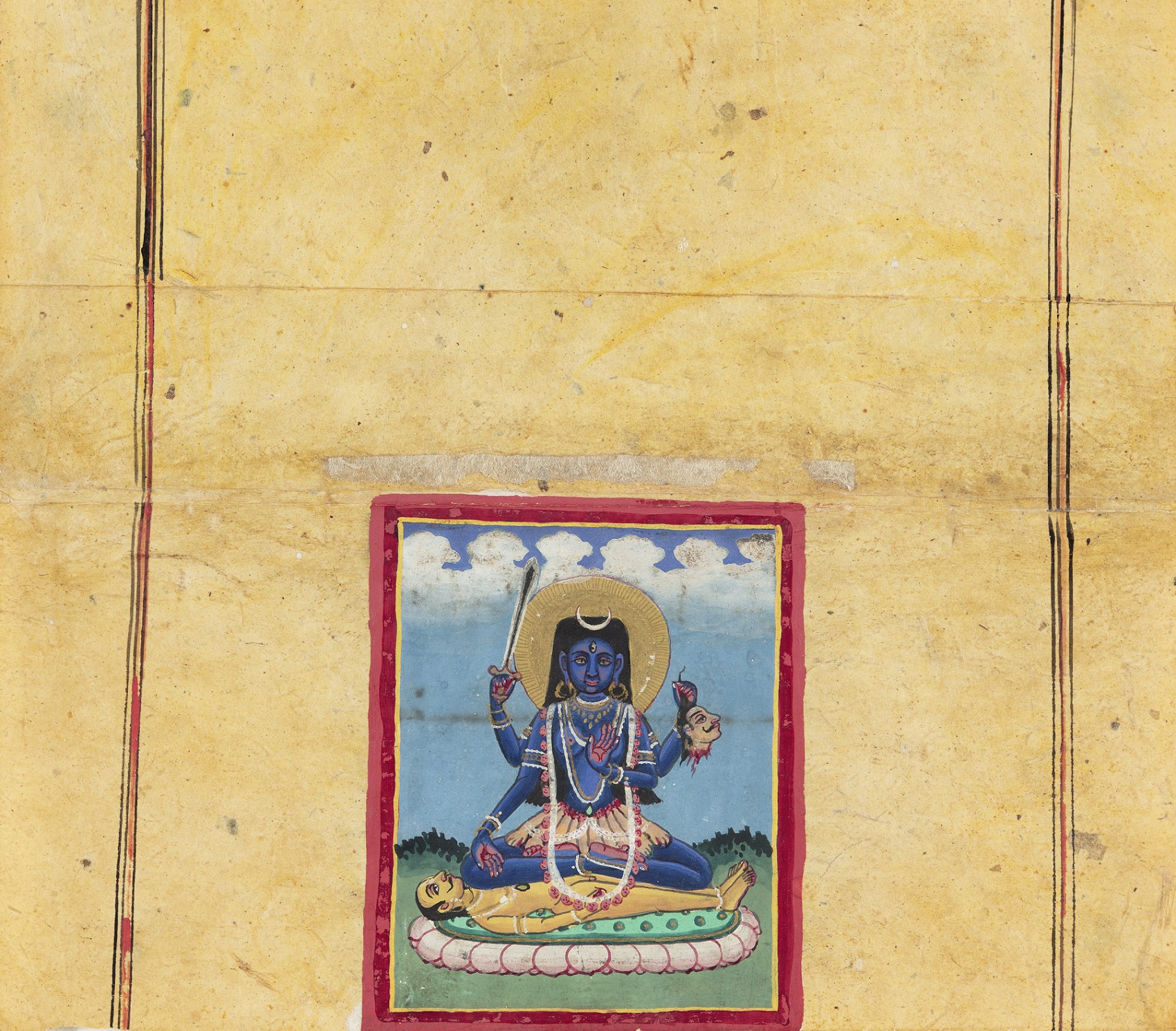

Unidentified Artist (Miniature Painting)

The Goddess Devi as Shmashsâna

Gouache highlighted with gold and silver pigment on paper, late 19th century, 7.0 × 7.7 in.

Collection: DAG

Besides the Devi Bhagavata Purana, she also suggests Devi Mahatmya to be an important source for her iconography. Gayatri Sinha writes, ‘The Pahari schools of painting aestheticise Kali even in her fierce aspect. Typically, Kali is depicted in the cremation ground, with corpses, jackals and carrion birds, while she is seated or walking on the prone body of Shiva. She is frequently also shown adorned with a golden crown and halo, in a young or old and ghoul-like form. While Shiva may be passive and peaceful, Kali is fully energised, bearing a decapitated head and a sword in her left hands, while her right hands hold the gestures of the Abhaya and dhyana mudras.’ |

|

|

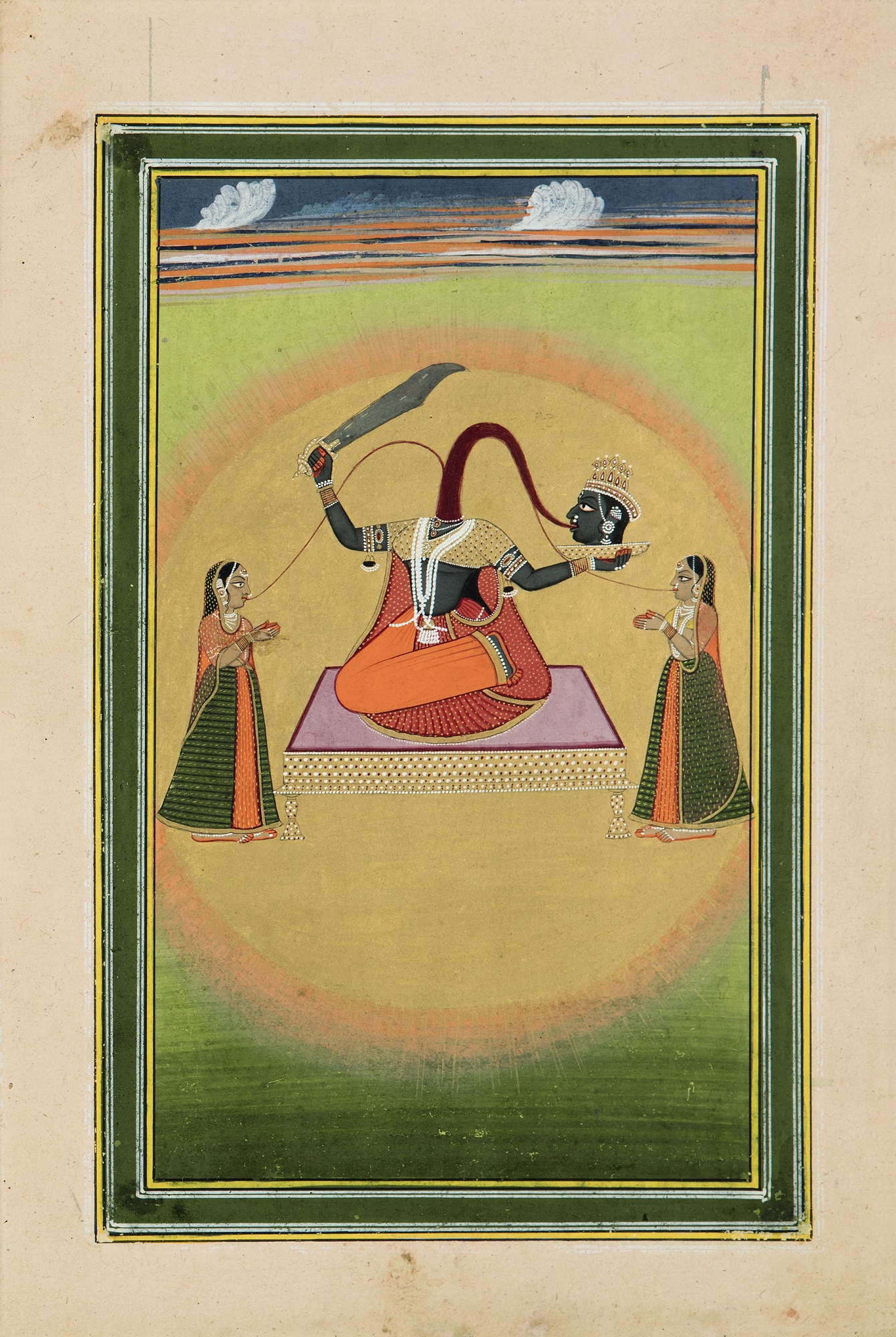

Jaipur Artist (Miniature Painting)

Chhinnamasta

Tempera highlighted with gold and silver pigment on paper, c. 1840, 11.5 × 7.5 in.

Collection: DAG

Jaipur Artist (Miniature Painting)

Durga confronts the Bull Demon, Mahisasura (An Illustration from a Markandeya Purana Series)

Tempera highlighted with gold pigment on paper, c. 1830, 10.2 × 13.2 in.

Collection: DAG

In Rajasthan, the depiction of Kali often aligns with the broader Hindu iconography prevalent in the region. While retaining core elements such as her fierce demeanor and association with destruction and renewal, Kali's depiction in Rajasthan might incorporate local artistic styles and cultural nuances. Artworks of Kali in Rajasthan may emphasise her wrathful aspect, often portrayed standing or dancing atop Lord Shiva, with her tongue protruding and wielding weapons to represent her power to overcome evil forces. The regional artistic motifs and styles of Rajasthan influence the depiction of Kali in this context. |

|

|

Unidentified Artist (Glass Painting)

Mahisasuramardini

Gouache highlighted with gold and silver pigments on glass (reverse painting), late 19th century, 19.0 × 13.7 in.

Collection: DAG

Unidentified Artist (Glass Painting)

Jagaddhatri

Gouache highlighted with silver and gold pigments on glass (reverse painting), late 19th century, 18.2 × 13.5 in.

Collection: DAG

Another fascinating subcategory of works on Kali included in the exhibition are the reverse glass paintings depicting the goddess in action. Reverse glass painting is a unique art form where glass is used as the canvas instead of traditional materials like canvas or paper. This technique involves painting on the back side of the glass, creating a distinctive visual effect. The process of reverse glass painting typically includes three main steps: line art, painting of internal areas, and background. Artists start with line art to outline the primary idea of the painting, followed by filling in internal areas and finally adding the background. This method requires careful planning as each layer of paint affects the final outcome. The art form has a rich history, with examples found in various cultures like Europe, China, Japan, India, and Senegal. In fact, looking at some of the facial features employed in the works, it is possible to speculate that these may have been made originally outside India, perhaps in a Chinese port city, even if it was intended for an Indian patron or devotee. The reverse glass painting, therefore, becomes a node in the global history of Kali in art. |

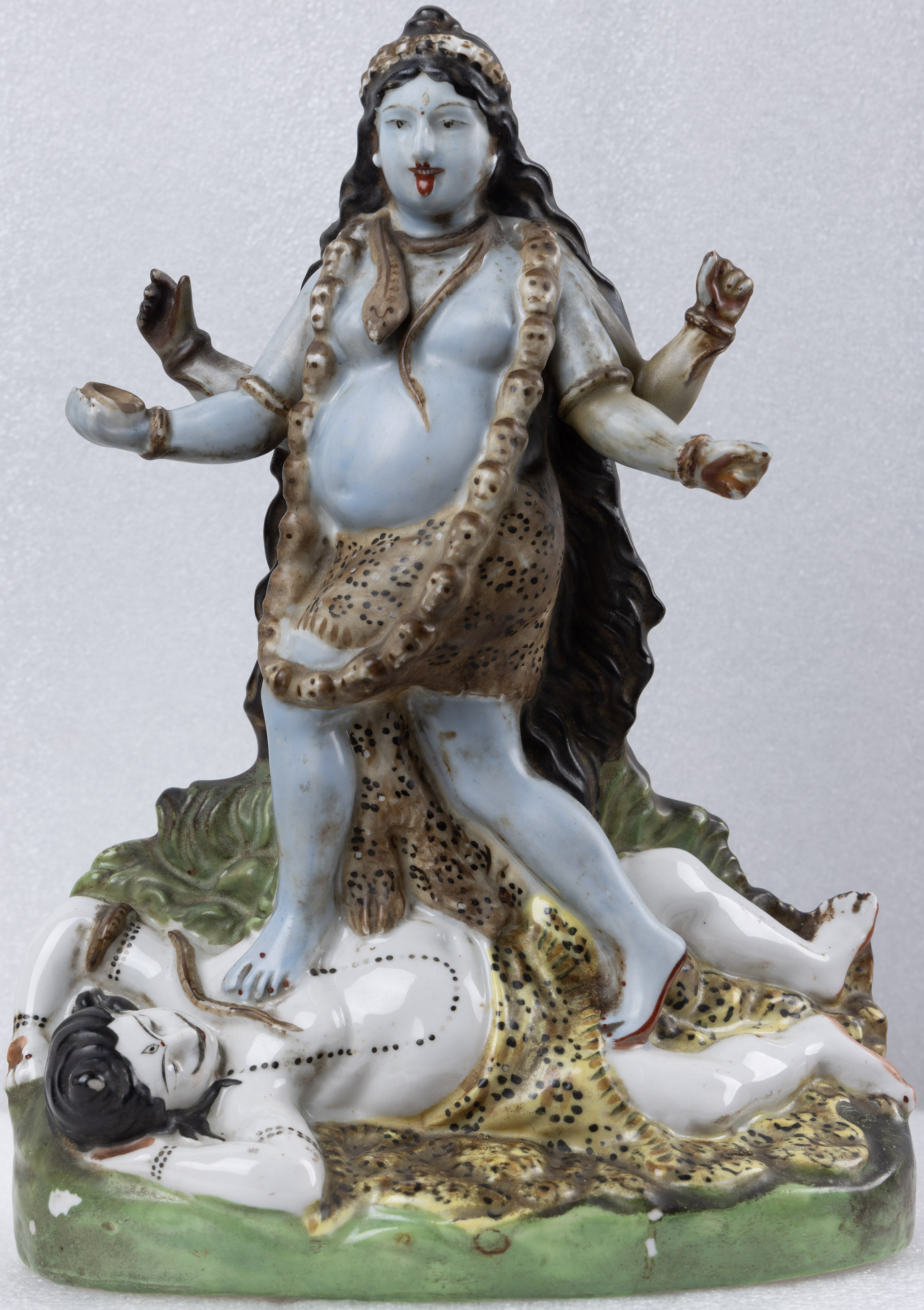

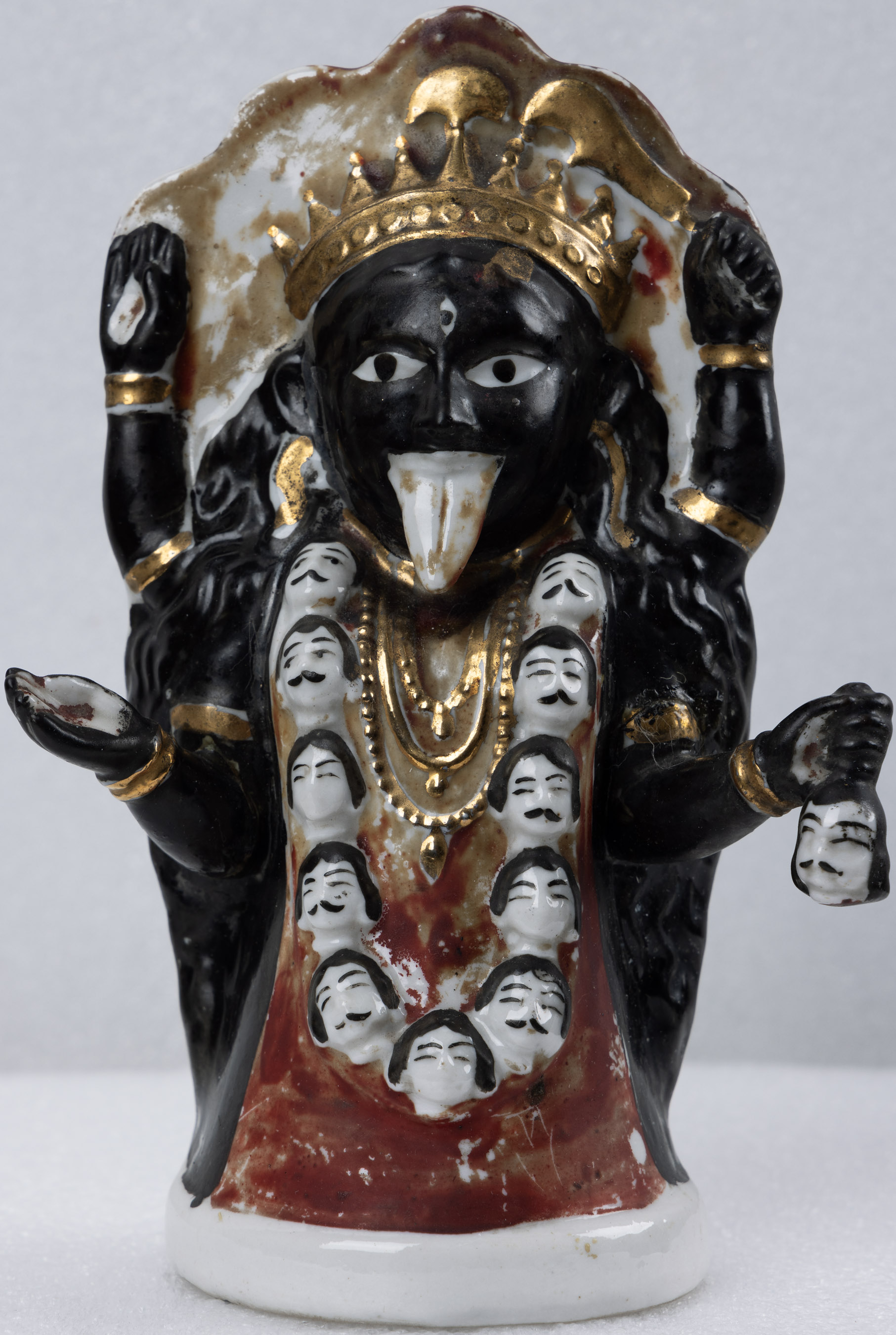

Unidentified Artist (German Porcelain)

Tara

Painted and glazed porcelain, early 20th century, 10.0 × 7.7 × 4.0 in.

Collection: DAG

Unidentified Artist (German Porcelain)

Dakshinakali

Painted and glazed porcelain, early 20th century, 7.0 × 4.7 × 2.7 in.

Collection: DAG

The exhibition also includes ceramic sculptures and porcelain works depicting the goddess. They provide a tangible form through which devotees can connect with and worship the goddess. Worshipping Kali is believed to bring protection, empowerment, and spiritual transformation. The ceramic sculptures of Kali, many of which are produced in Bengal, serve as cultural artifacts and are often found in temples, shrines, and homes, symbolising devotion and reverence towards the goddess. |