|

DAG Museums Fabric of Freedom: The struggle for independence through artUpasana Das September 01, 2023 DAG Museums works with students to develop new perspectives on Indian history and art. To celebrate Independence Day a little differently, we helped students of Indus Valley World School (IVWS) to create an exhibition using the artworks from the DAG collection, as they explored the untold stories of women, unique approaches towards claiming one’s due rights, and the rise of indigenous businesses. |

|

Do you remember the images in your history textbook? Did you ever spend any time observing or analyzing them? A heavily blue-tinted image of indigo plants being carried to the factory accompanies a chapter on the Indigo Revolution in the class eight CBSE history textbook. Its blurry contours make details barely comprehensible, which defeats any intention the author may have of inviting a deeper engagement with the image. |

|

|

Art Lab at Ek Tara Learning Centre with the students of Ek Tara and Future Hope

Art Lab at Ek Tara Learning Centre with the students of Ek Tara and Future Hope

While developing education programmes for learners we were pleased to find many familiar artworks from the DAG collection in the pages of the CBSE and West Bengal Board textbooks, though they were often grainy and hard to see clearly. We found that despite an exposure to a few examples of Indian art, students and often teachers did not have the tools to read these images or use them as a part of the learning process. The question of why art should be used in classrooms, how it could transform the learning process, and what we could do to facilitate this change led us to develop the DAG Museums Education Programme last year, launching Art Lab at Indus Valley World School, Kolkata. |

|

Art Lab, a travelling pop-up exhibition with facsimiles of artworks from the DAG collection has travelled to six schools and and reached over 2000 students since April 2022. Indus Valley World School invited us back a year later to develop an art-based module and participatory exhibition for Independence Day, in line with our methodology for Art Lab. |

|

|

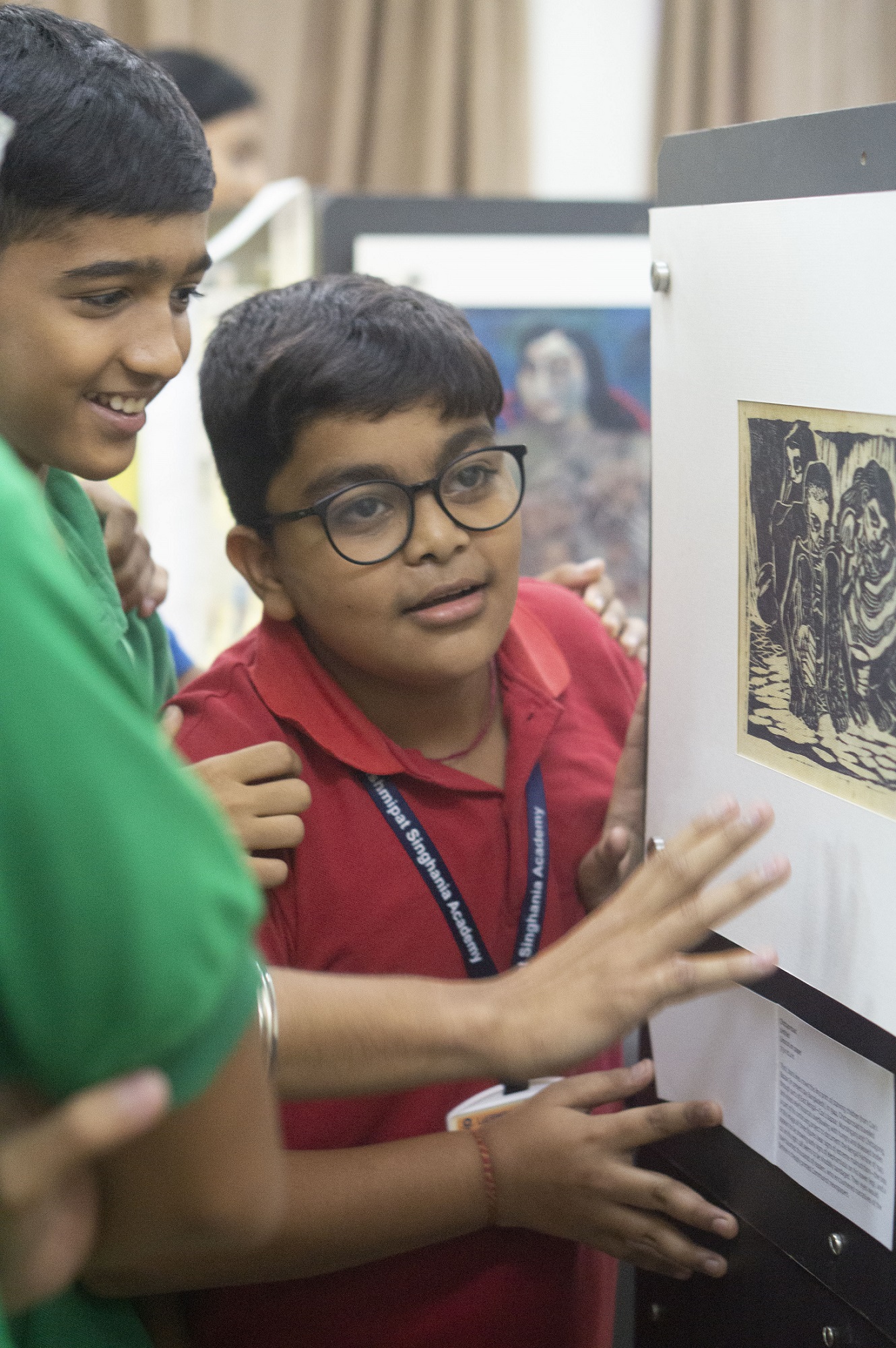

Students engaging with the DAG artworks and activity sessions during Art Lab

Students engaging with the DAG artworks and activity sessions during Art Lab

Students engaging with the DAG artworks and activity sessions during Art Lab

This time around the project would not only involve students and their parents, as with Art Lab, but would serve as an example of art-based learning for fifty teachers from the Kolkata Teachers' Centre network with whom we would be sharing the entire process. It would be an opportunity to draw from a year of programme development and demonstrate the methodology we had fine-tuned through workshops and projects with diverse learner groups and educators. The one feedback we had received from the teachers we had worked with over the past year was that we needed to connect the learning modules we develop to the textbook, so that’s where we started. The interwoven stories of textiles, trade and freedom ties together the many stages of the freedom struggle and cuts across different chapters at learning levels, and so the story of the ‘Fabric of Freedom’ became the focal point for learning module and the final exhibition. |

|

‘Rather than sow indigo, I will go to another country. I would rather beg than sow indigo.’ - Hadji Mulla, an indigo cultivator of Chandpore, Thana Hardi, during the Indigo Rebellion, as quoted in the CBSE Class 8 History textbook. |

|

|

A frame and structure inspired by the iconic charkha

A frame and structure inspired by the iconic charkha

A frame and structure inspired by the iconic charkha

A charkha-like display was developed as the framework for the exhibition to evoke the theme. This would hold a collection of artworks from the DAG collection along with five textile scrolls created by students, that come together across the frame to represent the various strands of the freedom movement and the complex stories of textiles in the subcontinent. A map of colonial fabric trade routes, from India to the U. K., Africa and Japan would dot the floor as an interpretive layer, setting the broader historical context. |

|

‘The evening's programme closed with a bonfire of foreign cloth. It was already dark. Suddenly the darkness was lit up by a red glare. A fire was lighted. A couple of boys wearing Gandhi caps went round begging people to bum their foreign cloth. Coats and caps and upper cloth came whizzing through the air and fell with a thud into the fire, which purred and crackled and rose high, thickening the air with smoke and a burnt smell. People moved about like dim shadows in the red glare. Swaminathan was watching the scene with little shivers of joy going down his spine.’ - R. K. Narayan, Swami and his Friends (1935) |

|

Chittaprosad Untitled Ink on scraper board Collection: DAG |

Abanindranath Tagore

Bharat Mata

Chromolithograph on paper, 10.7 x 6.0 in.

Collection: DAG

Unidentified Thanjavur Artist

Silk Weaver and Wife. c. 1770s

Gouache highlighted with gold pigment on paper

Collection: DAG

With the theme of fabric and freedom in mind we made a selection of artworks—from eighteenth century Company painting of silk weavers in Thanjavur to Abanindranath Tagore’s Bharat Mata from 1905 who carried a piece of cloth in her hand. Our work in museums and exhibitions with young people has shown us how looking closely at artworks and interpreting it can be a powerful way to introduce students to topics in their textbook, but more importantly can be an entry point into complex and difficult ideas that go beyond their prescribed syllabi. It can create a space for students to participate in the learning process, and develop their own perspective, while also allowing them to identify what they don’t know and ask critical questions to further their learning. The artworks brought this rich museum experience into the classroom as we began the process of developing the exhibition together. Using prompts and thinking critical tools students began to confront these unfamiliar images, learning that they perhaps already know more about art than they give themselves credit for. |

|

‘The child looks and recognizes before it can speak. But there is also another sense in which seeing comes before word. It is seeing that establishes our place in the surrounding world; we can explain that world with words, but words can never undo the fact that we are surrounded by it. The relation between what we see and what we know is never settled.’

|

|

Ramendranath Chakravorty Untitled Water colour on paper Collection: DAG |

Students at work

Students at work

Students at work

Students at work

Students were asked to step into the lives of the individuals depicted in the artworks. One group was given Chittaprasad's scraper board drawing of the Santhal Rebellion and many identified with the male figure and imagined him as one of the Murmu brothers. Others were interested in the woman stooping over the dead figure of a man, and after doing a little research, they discovered the revolutionary Murmu brothers had two sisters Phulo and Jhano who also fought during the rebellion. Through the use of perspective-taking tools, they stepped into various different events and explored them in depth with liberty to create and experiment. While studying history in school, students are often directed towards a single narrative. By engaging with the artworks and the varied perspectives they present, students had to try modes of learning that challenged the way knowledge is usually produced in their classrooms. They were encouraged to look at museum and gallery collections, newspaper archives, literature, music and films to develop a more granular reading of history, and understand that historical events continue to have effects on the present day. |

|

‘It’s impossible to study seriously if the reader faces a text as though magnetized by the author’s word, mesmerized by a magical force; if the reader behaves passively and becomes ‘domesticates,’ trying only to memorize the author’s ideas; if the reader lets himself or herself be ‘invaded’ by what the author affirms; if the reader is transformed into a ‘vessel’ filled by extracts from an internalized text. Seriously studying a text calls for an analysis of the study of the one who, through studying, wrote it. It requires an understanding of the sociological-historical conditioning of knowledge. And it requires an investigation of the content under study and of other dimensions of knowledge. Studying is a form of reinventing, re-creating, rewriting.’

|

|

|

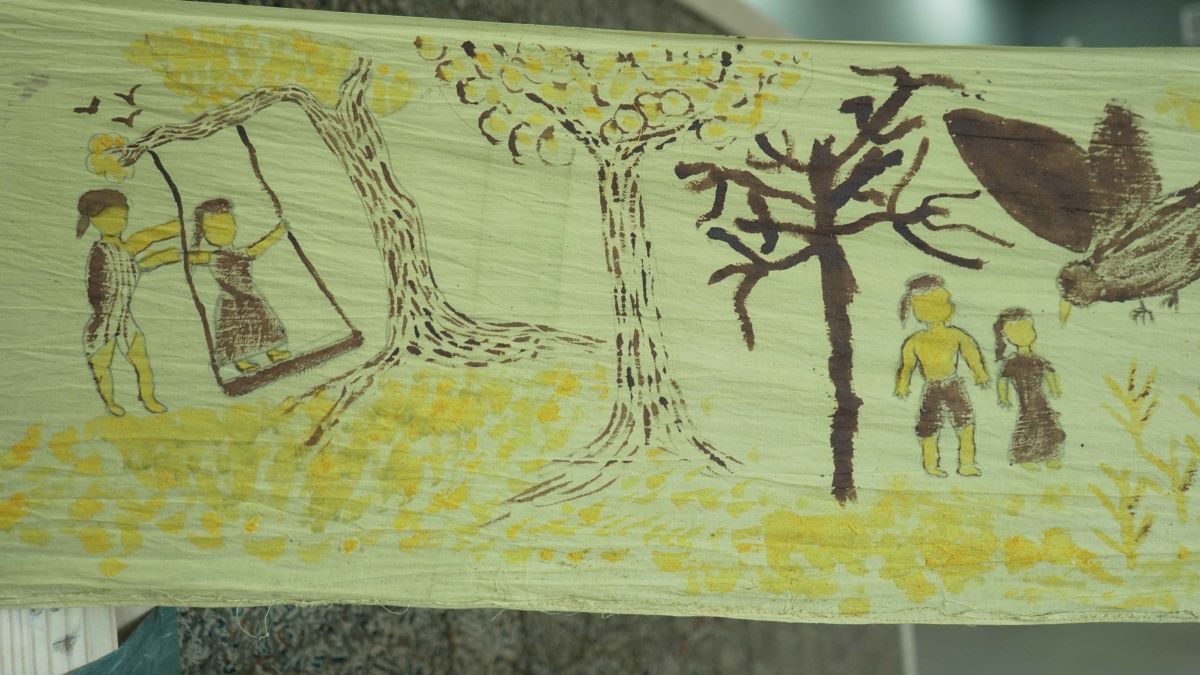

THE SCROLL ON THE SWADESHI MOVEMENT CREATED USING APPLIQUE

Painting using natural dyes and pigments

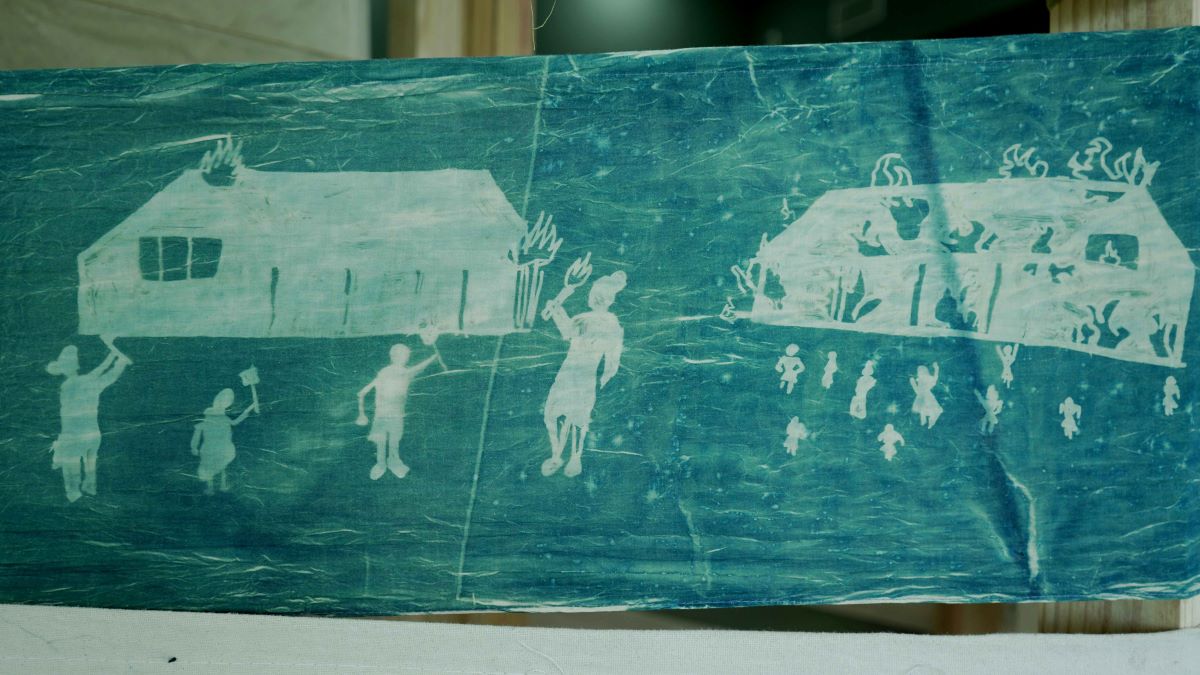

A surreal narrative depicting the Santhal rebellion, with the bird hovering above the revolutionaries representing the British

The Indigo rebellion in cyanotype

Stepping into the shoes of researchers, artists and curators, students were introduced to the structure of the exhibition, the charkha frame, and their task at hand—working in five groups to create five textile scrolls, each depicting one strand of the freedom struggle. The characters from the paintings they had studied would come alive in these scrolls, each made with a different printing, stitching or dyeing technique. Reflecting on the process of developing their characters, balancing fact and fiction, creating their storyboards and transferring their narratives onto the scrolls, students mentioned they enjoyed the freedom of shaping their own point of view on the past. They also appreciated having the liberty to fail. While working in groups, things were certainly not always peaceful and things did not go according to plan. While working with difficult processes like linocut, they struggled to get the paint on fast enough for the imprint to appear clearly on the fabrics, and amidst days of heavy rainfall, the group working with cyanotype had difficulty with calibrating the exposure and had to redo their scroll. However, they found ways to organize themselves and work through the challenges, and the small wins along the way propelled them towards completing their final projects. |

Students explaining the exhibit on the opening day at IVWS

Teachers and parents visiting the ’Fabric of Freedom’ exhibition

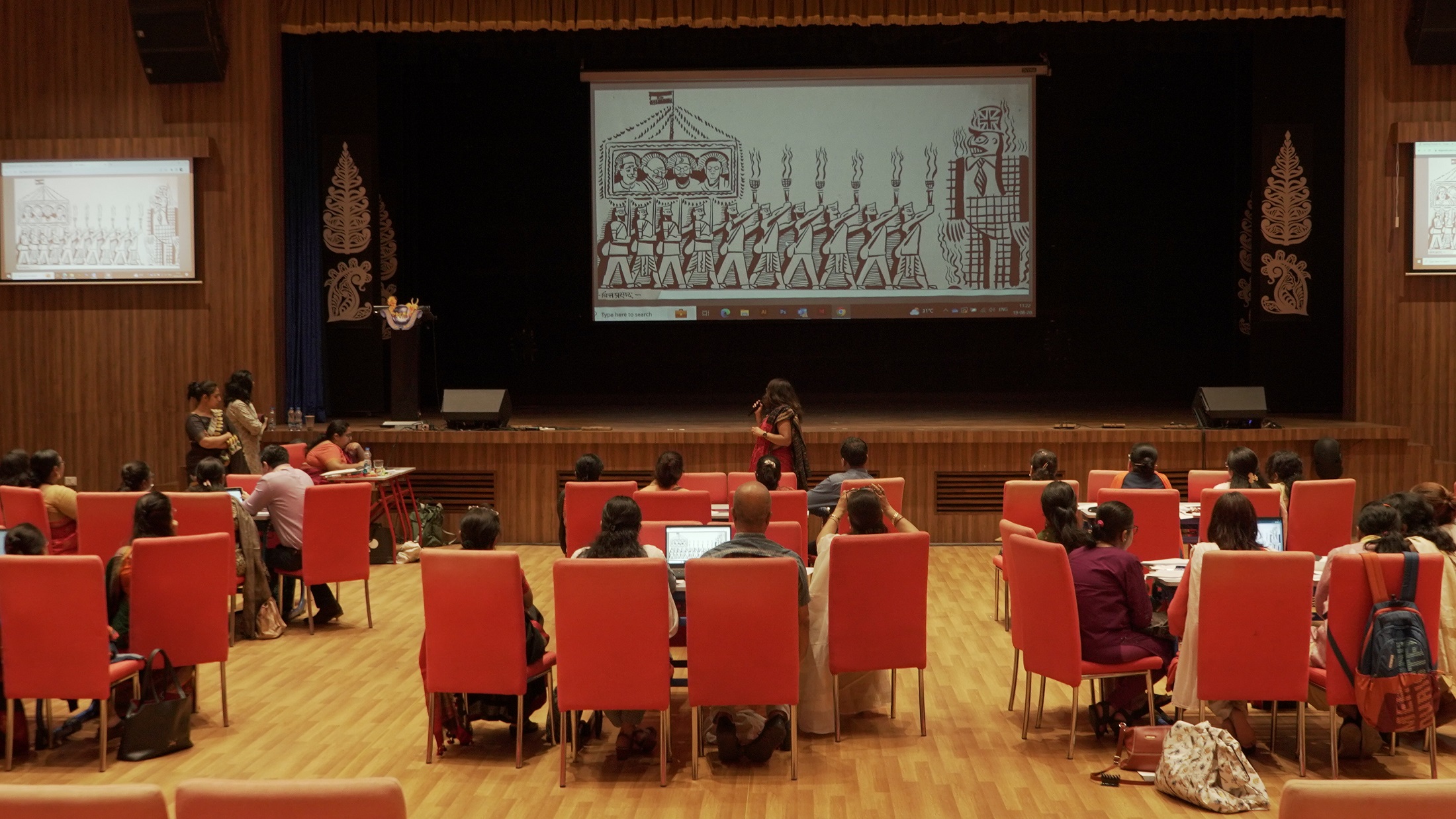

Teachers’ Workshop at IVWS

Teachers visit the 'Fabric of freedom' exhibition

On the opening day students presented the exhibition and their scrolls to their parents, teachers, and peers, and students from other schools and other classes visited the exhibition over the week. On the final day of the exhibition, we organised a workshop for the Teachers’ Center, with fifty educators coming in from twenty schools in the city. The workshop was conceptualized to equip teachers with tools they could use to integrate art at different stages of the learning process. At the workshop the teachers were excited to consider the possibilities of this venture. One of the teachers said, ‘The fun-filled activities by the facilitator displayed techniques that teachers could use in the classroom which would help students to focus better and keep the students more attentive in the classroom.’ While this was certainly an important outcome, the workshop and the ‘Fabric of Freedom’ exhibition demonstrated how art could create learner-centric classroom, where students delve deeper into their prescribed syllabus, but ultimately go beyond the textbook, and develop the tools to drive their own learning. |

|

While the teachers we have worked with will interpret the tools we shared in their own ways and amplify our efforts to bring art into classrooms, Art Lab remains our space for innovation and experimentation as the pop-up exhibition travels to schools across Bengal. While methods and tools have varied across schools as we adapted the module for Bengali-medium schools, first generation learners, and informal learning spaces, the core focus remains on using art as starting point for students to determine what they need to learn more about, what they care about, and how they want to connect the past to the present. |

|

|