Estranged visions: The impact of Surrealism on Indian modern Art

Estranged visions: The impact of Surrealism on Indian modern Art

Estranged visions: The impact of Surrealism on Indian modern Art

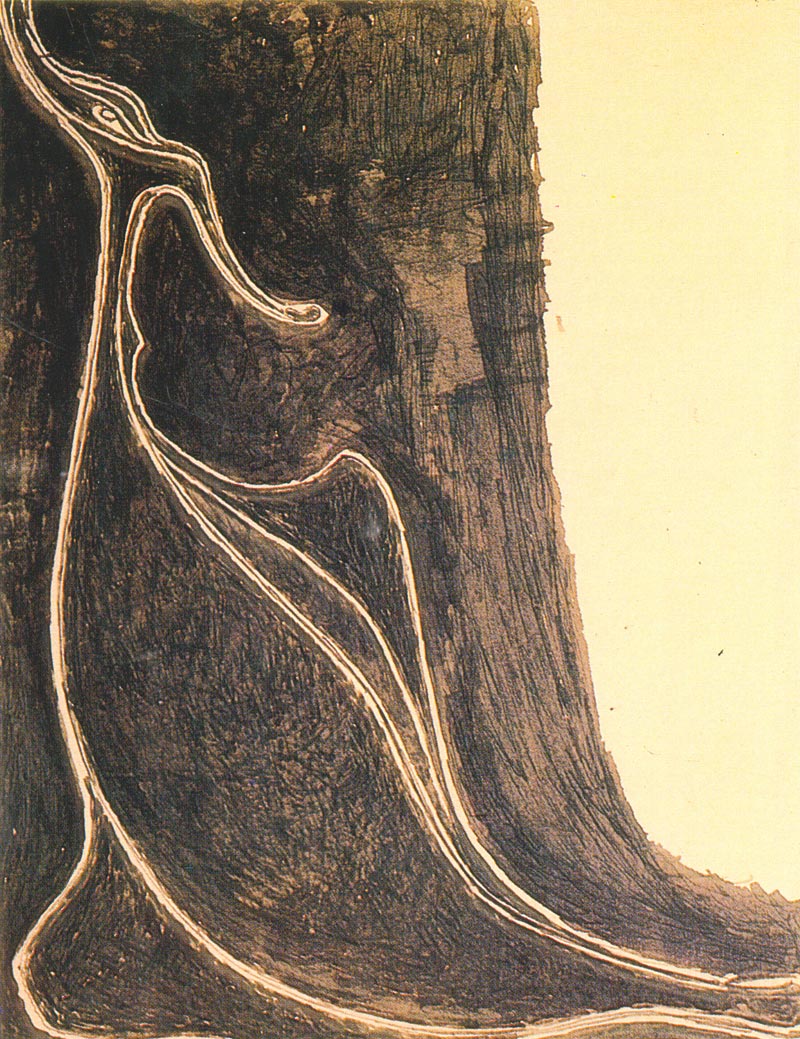

K. C. Pyne, Untitled (detail), 2000, Oil on canvas, 20.0 x 25.7 in. Collection: DAG

Nearly a year after France concluded its grand celebration of the ‘Centenaire du Surréalisme’ (Hundred Years of Surrealism), Sotheby’s Paris held an auction titled Surrealism and Its Legacy, featuring a René Magritte painting that sold for 10,652,500 euros and a Paul Delvaux work that fetched 2,360,500 euros. This comes after the Belgian surrealist Magritte joined the 100 million club at a Manhattan auction in November 2024, setting a new record not only for the artist but for any surrealist artwork sold at an auction. The piece, titled L’Empire des Lumières (or, Empire of Light), which frames a sunlit sky with a shadowy street below, ignited a ten-minute bidding war between telephone buyers before achieving its historic price.

This milestone places Magritte in the company of artists like Gustav Klimt, Leonardo da Vinci, Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Pablo Picasso in the elite nine-figure club. The growing demand for Surrealist work and record-breaking sales over the last few years come right as France’s homegrown artistic revolution celebrates a centenary.

|

Rene Magritte, The Empire of Light, c. 1939-1967. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

According to a recent insight report, Bretonian Surrealist artworks (named after the official founder of the movement, Andre Breton) have risen significantly in value in the global art market- from USD 726.1 million to USD 800.7 million just within the time span of 2018 to 2024. The iconic movement, now occupying about 16.8% of the art market, originated in the aftermath of the First World War in what was then considered the art capital of the world, Paris. The record-breaking eighteen months of March 2024 to September 2025 especially saw benchmark sales. As Magritte’s L’Empire des Lumières joined other nine-figure heavyweights, women artists, such as Leonora Carrington and Dorothea Tanning have also been central to the market growth for the genre- driving a 411.4% rise in sales, from USD 7.9 million in 2018 to USD 94.3 million in 2024. With investor confidence in Surrealism continuing to grow worldwide, DAG turns its gaze homeward to examine India’s own surrealists and the evolving contours of the Indian market for the genre.

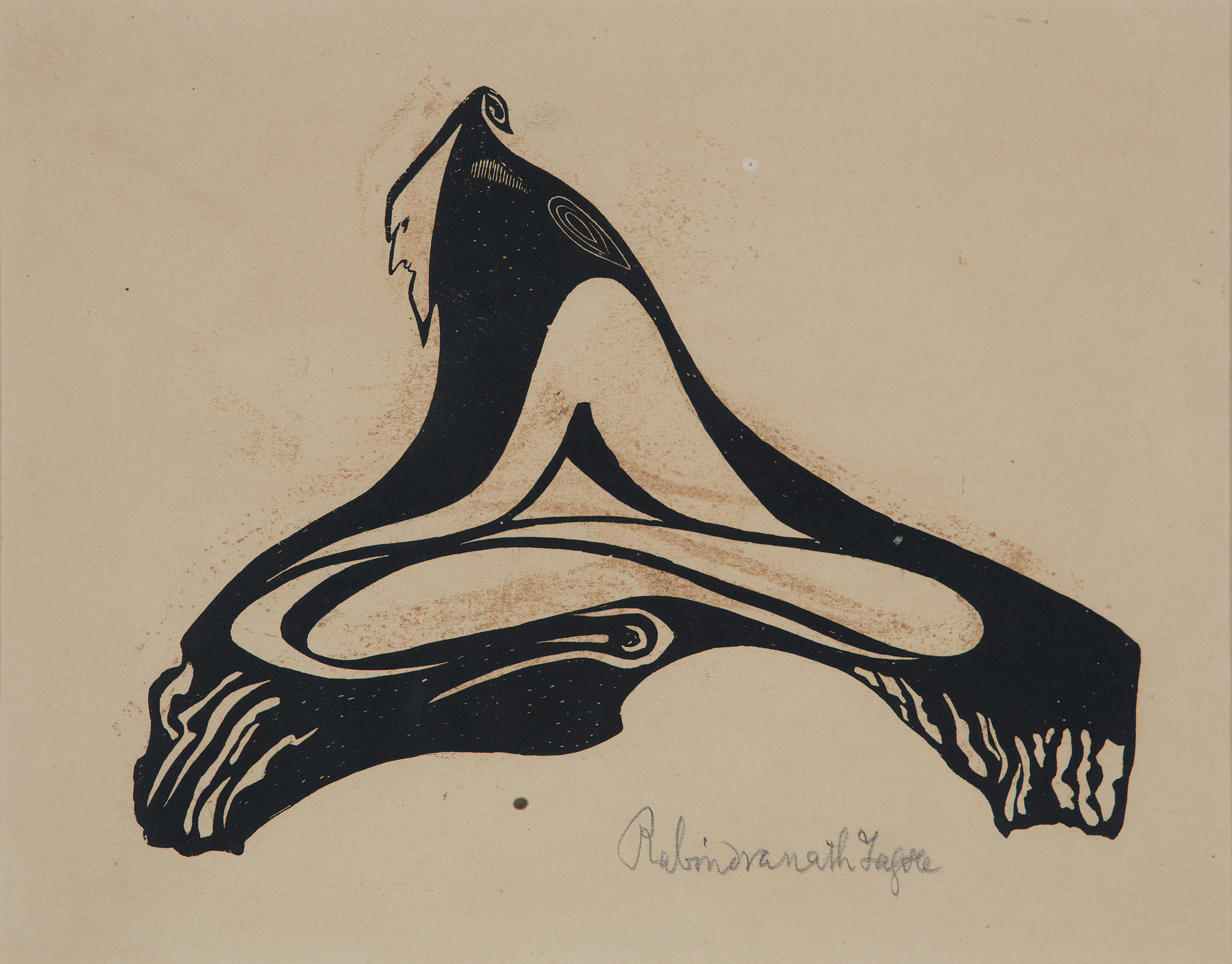

Rabindranath Tagore, Untitled (Namaz), Woodcut on newsprint paper, 8.7 x 11.2 in. Collection: DAG

Often regarded as the father of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud was the first to propose that dreams could reveal aspects of the mind that lie beyond conscious awareness. This formed the basis of his psychoanalytic theory. In The Interpretation of Dreams (1899), Freud outlined how the unconscious remains active during sleep, producing dreams that may elude memory upon waking. Although his ideas were met with scepticism a century ago, they profoundly influenced artists and writers, who began to investigate the realm of the unconscious and, by extension, the unreal. In 1924, French poet André Breton introduced Surrealism to the world through his text, Le Manifeste du Surréalisme (The Surrealist Manifesto). Deeply influenced by Freud’s theories of the unconscious mind, Breton argued that logic and reason constrained the full expression of human potential. In the aftermath of the First World War, poets, artists, and philosophers began questioning the rigid boundaries of a civilisation driven by reason and progress—boundaries that had, in their view, led to immense destruction and loss. For Breton, genuine creativity lay in releasing these restraints and plunging into the dreamlike, instinctive depths of the mind. Surrealism thus emerged as a revolutionary movement across literature, art, and film, shaped by the strange and boundless language of the subconscious.

|

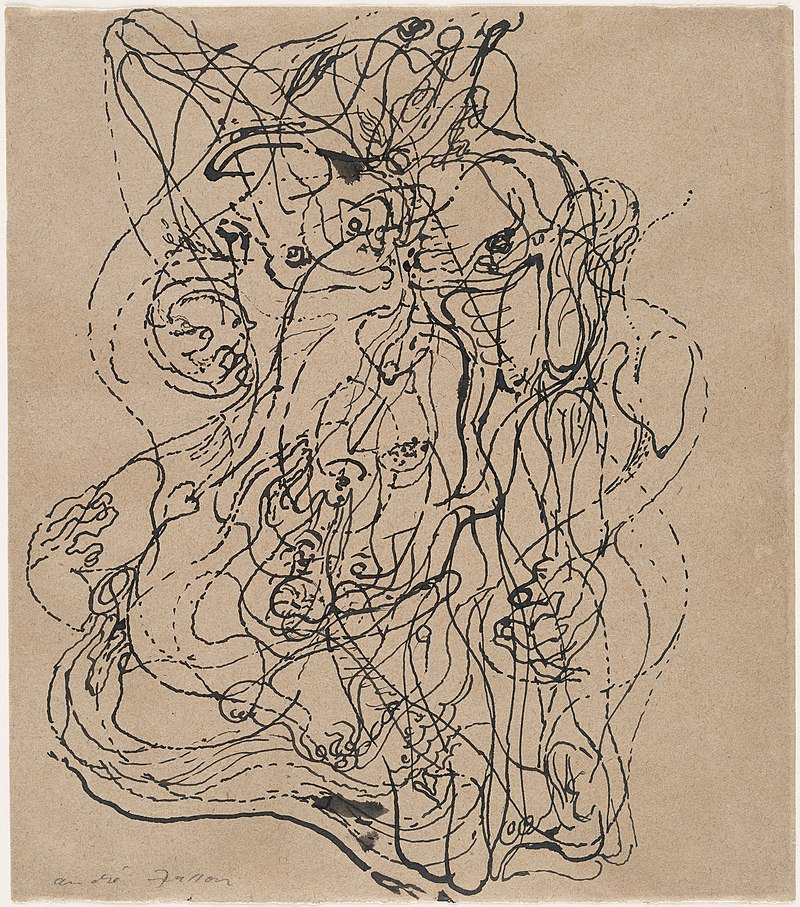

Andre Masson, Automatic Drawing, 1924, Ink on paper. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons and the Museum of Modern Art, New York |

What does Surrealism mean in India?

The roots of Surrealism lay in the earlier Dada movement, which arose during the First World War out of deep disillusionment with the senseless violence and mechanised logic of modern society. Dada artists renounced reason and order, producing absurd and anarchic ‘anti-art’ to protest against the rationalism they believed had led to war. They celebrated chance, satire, and irony, often mocking the very notion of art itself. While Surrealism inherited Dada’s fascination with the strange and unexpected, it pursued a different purpose. Rather than rejecting reality altogether, the Surrealists sought to uncover its deeper, hidden layers—those found within the unconscious mind. The word ‘sur’ in French means beyond, above, or in addition to, and it captures the movement’s goal to transcend both reality (which could also include the academic rules of Realism in painting) and conscious control. Through techniques such as automatic drawing, where artists resisted conscious modes of control, and dream-inspired imagery, Surrealist artists sought to access unfiltered imagination, revealing the extraordinary that lies just beneath the surface of the ordinary.

|

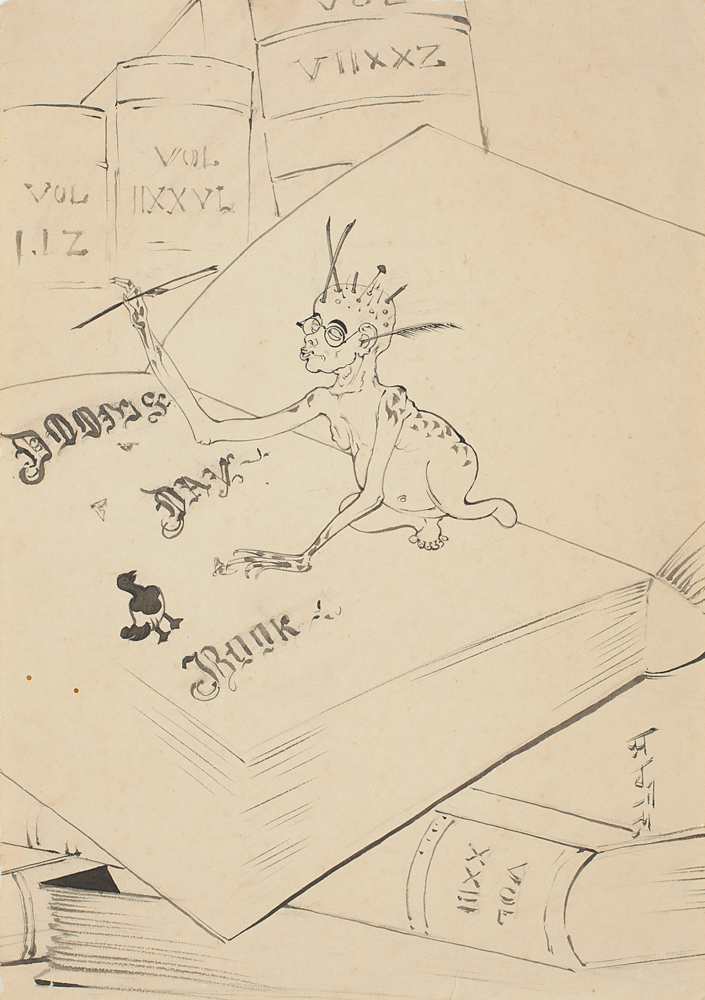

Abanindranath Tagore, Untitled, Ink on paper, 10.0 x 7.0 in. Collection: DAG |

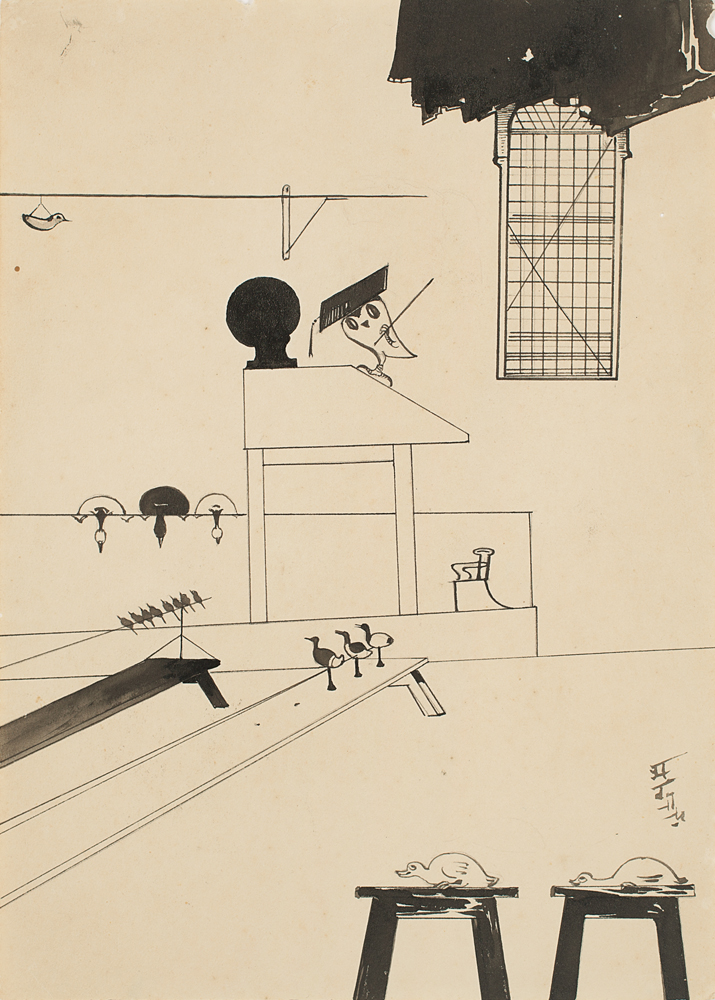

Artists of the Indian subcontinent adapted Surrealism to their own historical and social context, inspired by vernacular traditions, a mixture of folklore and myths, the geopolitics of the subcontinent (then in its late-colonial period), and stories that were passed down within communities. Their works frequently reference local iconography, folk and religious art, and include recurring motifs like animal-human hybrids, natural forms, deities, and sacred symbols. Unlike Bretonian Surrealism, Indian Surrealist art often places greater emphasis on the mysterious or symbolic power of imagery rather than on automatist methods.

|

K. C. Pyne, Untitled, 2000, Oil on canvas, 20.0 x 25.7 in. Collection: DAG |

At its heart, Surrealism was a liberatory movement. By the 1930s, Surrealism was making bold statements about politics and society. As Europe edged toward another war, the movement became a way to challenge authority and imagine alternatives to a broken world. However, this Western orientation has overlooked the profound ways in which Surrealist ideals resonated across the globe, wherever people attempted to pose challenges to the rationalised world order that supported noxious institutions like fascism or colonialism. Paris experienced such cross-cultural encounters when artist and Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore’s psychologically evocative art was exhibited in 1930—works inspired by his own explorations of the subconscious. It is worth pointing out that as modern artists in the western world innovated due to their exposure to non-western art forms, such as African and Indo-Pacific sculpture, surrealist artists also drew inspiration from a wide variety of sources that originated from ‘outside’ European cultural norms and forms.

|

Rabindranath Tagore, Untitled, Ink on paper, 13.5 x 4.7 in. Collection: DAG |

When Tagore’s drawings were exhibited in Paris in May 1930, they were received by European audiences within the same intellectual climate that had produced Surrealism. Tagore’s show was held at the Galerie Pigalle, a space that, only months later, would host the first major Exposition surréaliste. Thus, his art entered the European field at the exact moment that le surréalisme was consolidating its language of dream and irrationality.

Freud's ideas were also being received, adapted and critiqued in India at the same time. His engagement with Indian psychoanalysis is most vividly seen through his extended correspondence with Girindrasekhar Bose, an early pioneer of psychoanalysis in India and founder of the Indian Psychoanalytical Society in 1922. Bose came from a culturally eminent family and was involved in Bengal’s wider intellectual circles, which intersected with Tagore’s milieu. The poet and artist’s interest in psychoanalysis developed in his later years, during which he read works by Freud and other psychoanalysts and entrusted scholars at Visva Bharati with tasks related to psychoanalytic theory. While Tagore occasionally expressed reservations about psychoanalysis, Bose, who also critiqued the universalising thrust of Freud’s theories of the subconscious, actively engaged with these arguments and replied through essays and letters circulated in literary journals.

Rakhee Balaram argues that Tagore’s 1930 Paris exhibition challenges the Eurocentric standards of ‘the historical avant-garde'. The coincidence of his show with the Surrealists’ demonstrates that the exploration of the irrational and dreamlike was not exclusively European. Tagore’s visual language opened a parallel modernism or a ‘pirate Surrealism’, as she terms it, sailing beside Breton’s, but guided by a different compass of consciousness and ethics; along with a contending set of historically located cultural tropes and motifs.

This exhibition, therefore, represents an early moment of ‘global Surrealism’ before the term itself was fully internationalised. Tagore’s ink erasures and shadowy figures anticipate later modern Indian artists’ engagement with the subconscious—from his nephew Abanindranath’s Arabian Nights series and counter-intuitive book-making exercises, such as Khuddur Jatra, to Ganesh Pyne and Bikash Bhattacharjee’s psychological interiors.

|

Abanindranath Tagore, Untitled, Ink on paper, 10.0 x 7.0 in. Collection: DAG |

When Rabindranath Tagore exhibited his paintings at Galerie Pigalle, European critics saw in Tagore’s drawings a dreamlike mysticism; yet what they perceived as exotic fantasy was, as Balaram argues, a manifestation of the 'colonial unconscious', a negotiation between the moral burden of empire and the imaginative freedom of the self.

Tagore’s late works, composed through fluid ink washes and accidental forms and doodles, paralleled automatism but stemmed from a different engagement with interiority. They reflected his search for spirit rather than subconscious desire. As Balaram notes, his 'pirate Surrealism' redefined the avant-garde’s boundaries, proposing an alternative modernism grounded in introspection rather than rupture.

|

Rabindranath Tagore, Bird Fantastic. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

Such artistic exchanges were not uncommon at the time, as demonstrated by the Bauhaus Exhibition in Calcutta in 1922, which featured works by Tagore and Paul Klee—who was another significant figure in the development of Surrealist art (especially drawing), even though he was not officially associated with it. But Tagore’s Paris exhibition marks the first major relay between European and Indian experiments with the unreal, an antecedent to the dream-inflected practices that would surface in post-Independence India.

|

Gaganendranath Tagore, Untitled, 1921, Watercolour and gouache on handmade paper, 11.0 x 10.7 in. Collection: DAG |

Read about Indian artists’ surreal trajectories in the postcolonial period in the next part of this article