DRISHYAKALA

DRISHYAKALA

DRISHYAKALA

|

DRISHYAKALA Red Fort, Barrack No. 4 Delhi, 1 February 2019 – 12 April 2022 An exhibition by DAG |

|

How did the multiple trajectories of visual arts develop in the subcontinent? Where did they originate and how did their paths converge? Drishyakala offers a sweeping journey into the heterogenous histories of visual arts in India, from the first European travelling artists who drew landscapes to popular prints of the earliest woodcuts and lithographs evolving into the thriving advertising visuals of the 20th century. The exhibition is broadly divided into four categories, each exploring an unique area of development—the art of portraiture through photography and painting, oriental sceneries drawn by European travelling artists, popular prints from the late eighteenth century to post-independence and artworks of the nine National Treasure Artists. Together, these sections give brief glimpses into the dizzying variety of forms, styles and languages of South Asian art. |

|

Gaganendranath Tagore Bed of Arrows Water colour and gouache on paper Collection of Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi |

|

National Treasure Artists Nine artists find special mention in India as ‘art treasures, having regard to their artistic and aesthetic value,’ a directive by the Archaeological Survey of India in the 1970s. Spanning a period of one hundred years of art practice, these artists represent a diversity of art traditions and movements but unified by one common thread: a return to Indian roots through context, theme, subject and an engagement with identity. India’s art tradition had been rendered subservient to a Western-oriented approach as taught in the art schools from the mid-nineteenth century onwards. Artists adopted it to contextualise, first, her own history and mythology, and then localise it in a vernacular that found recognition and empathy among its Indian viewers. It addressed and paralleled, to an extent, the freedom movement, and images were co-opted by freedom fighters in an attempt to create visual icons that unified them under a pan-national banner. While the precursors of the nationalist movement created recognisable imagery based on the past, their most important distinction was to celebrate India’s rural resilience and countryside. The subaltern came to occupy a significant part of their work, and resulting images came to be associated with the freedom movement as well as India’s civilisational position and aspiration at the start of the twentieth century. This historic exhibition traverses the distinctive works undertaken by these nine artists, the common strands that bind them as well as the differences that set them apart from each other. |

|

Jamini Roy Untitled (Horse) Tempera on boxboard |

Amrita Sher-Gil

Untitled

Water colour on paper

Raja Ravi Varma

Untitled

Oil on canvas

Jamini Roy

Untitled (Baul Singers)

Tempera on board

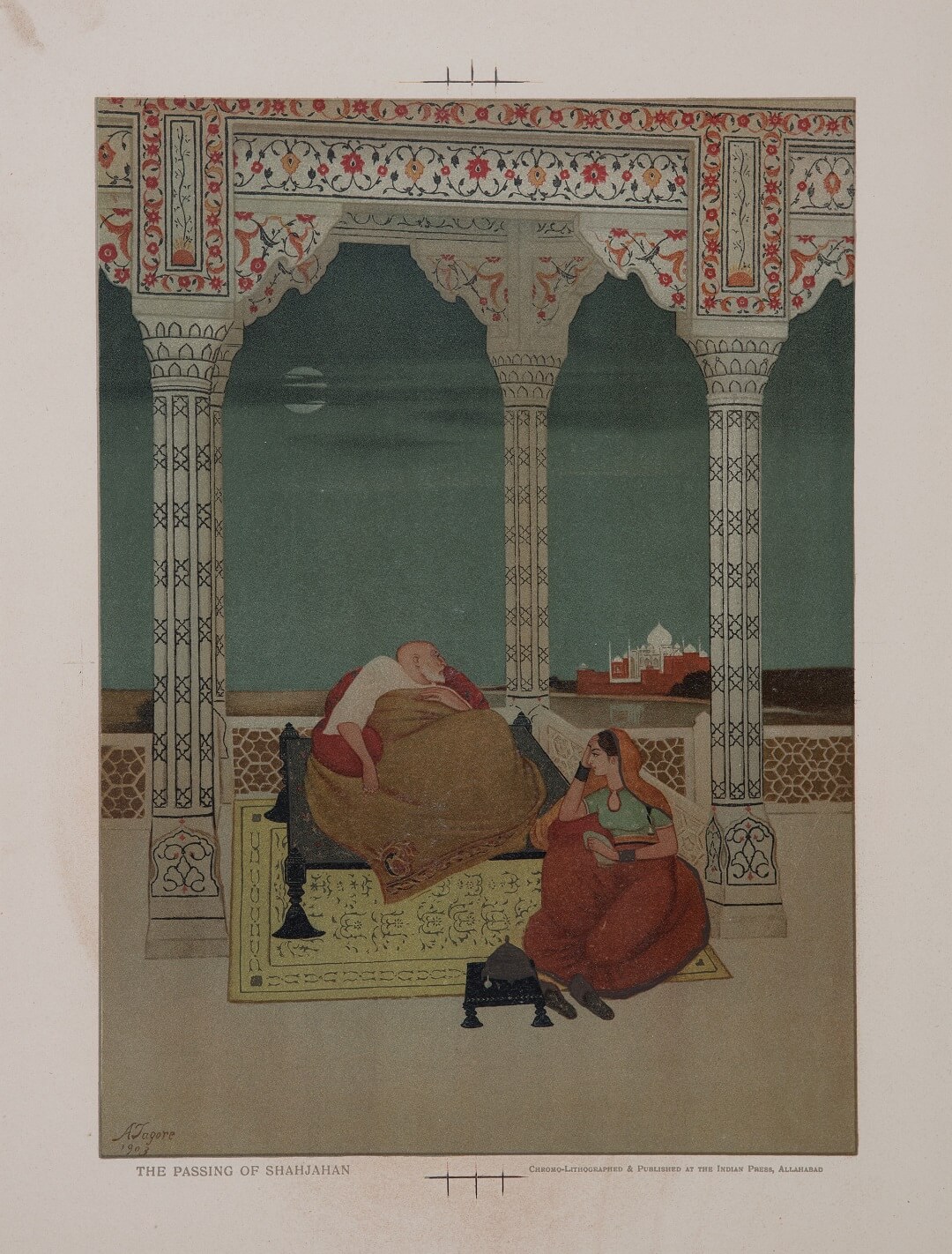

Abanindranath Tagore

The Passing of Shah Jahan

Chromolithograph on paper

Each of the nine artists have contributed to Indian art in unique ways. From Raja Ravi Varma’s imagination and popularization of popular religious images painted in the realist mode to Abanindranath Tagore’s attempt to fuse various artistic traditions from South East Asia, each artist formulated a new visual language of Indian art. |

Gaganendranath Tagore

A Noble Man

Rabindranath Tagore

Untitled

Nandalal Bose

Untitled

Sailoz Mookherjea

Untitled (Market)

The National Treasure artists testify to the sheer diversity of styles, media and languages that the subcontinent produced—from Gaganendranath Tagore’s incisive caricatures which attacked the British rule and 19th century social conservatism alike, Rabindranath Tagore’s formulation of a bold new language of portraiture to Sailoz Mukherjee’s fluid nature studies, which initiated a new, indigenous and modernist language of representing nature.

|

|

|

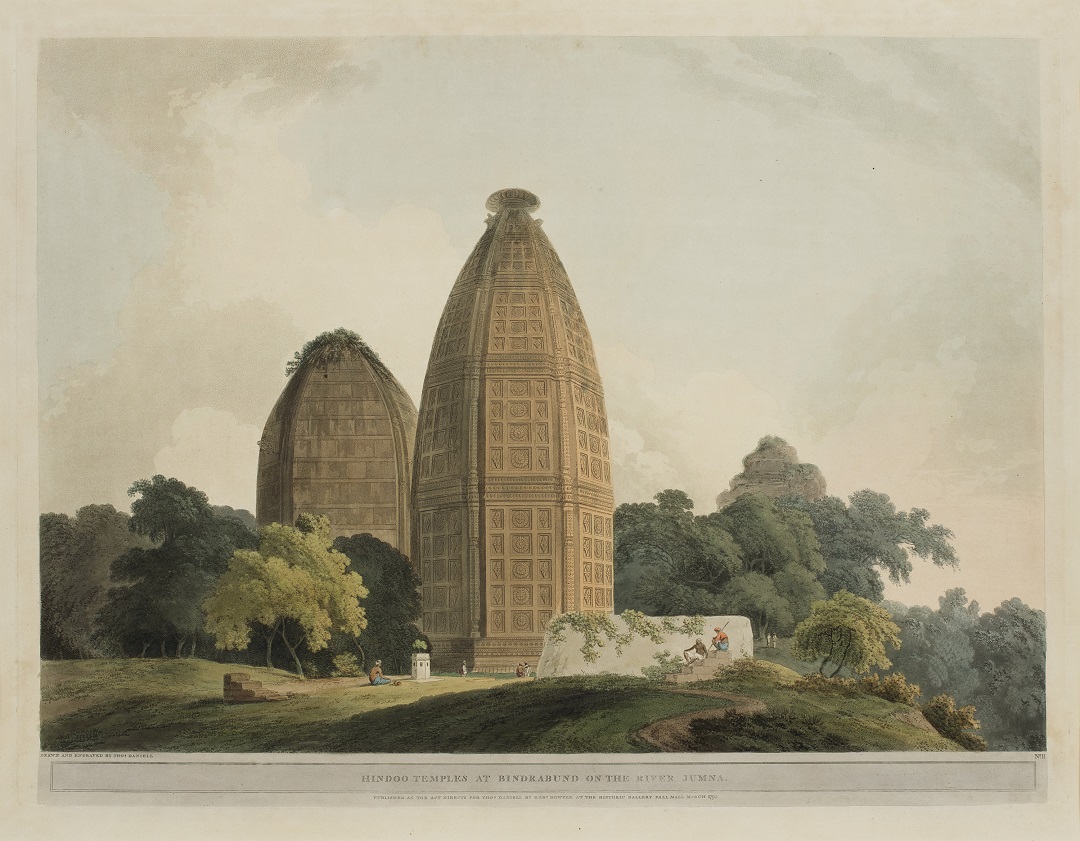

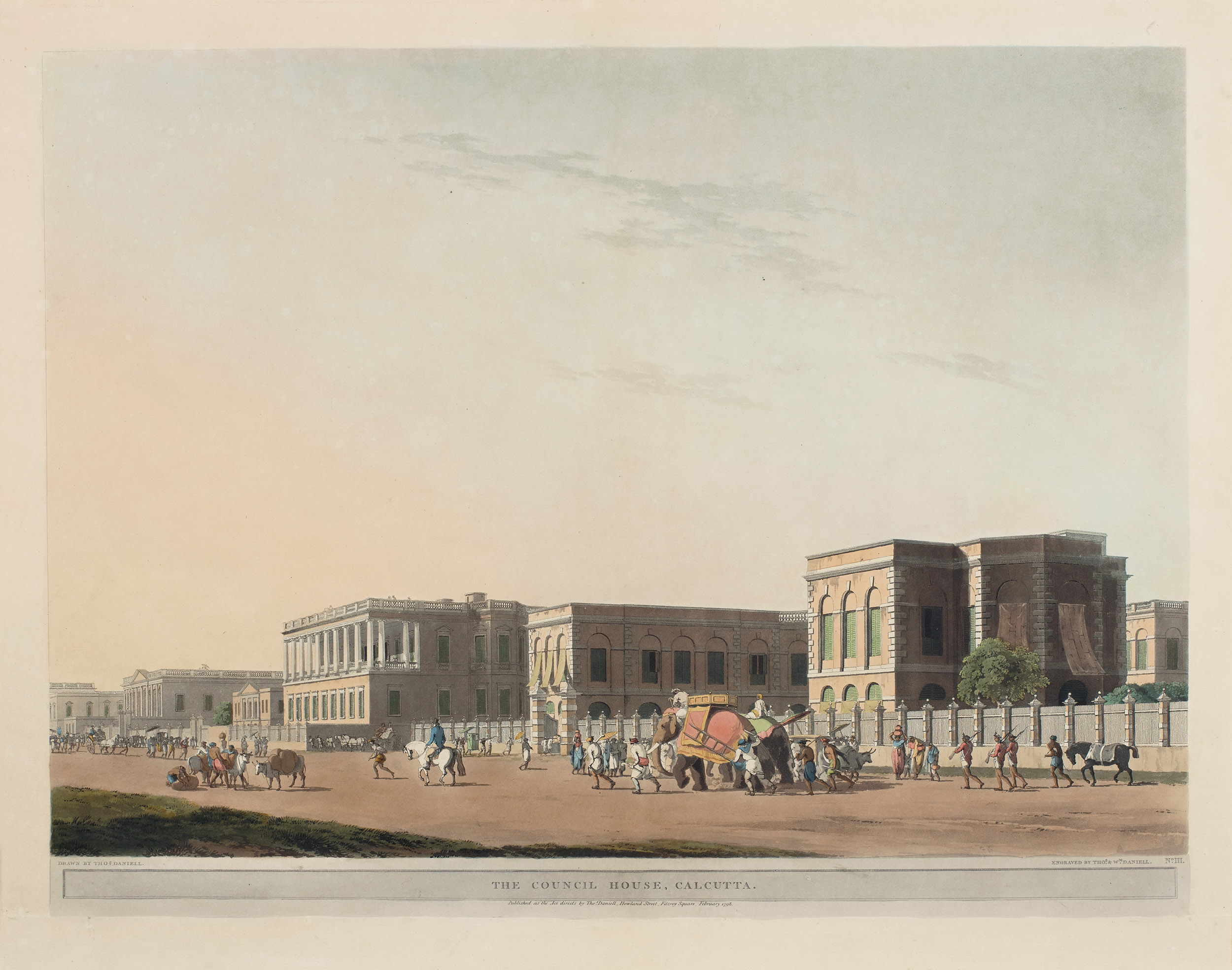

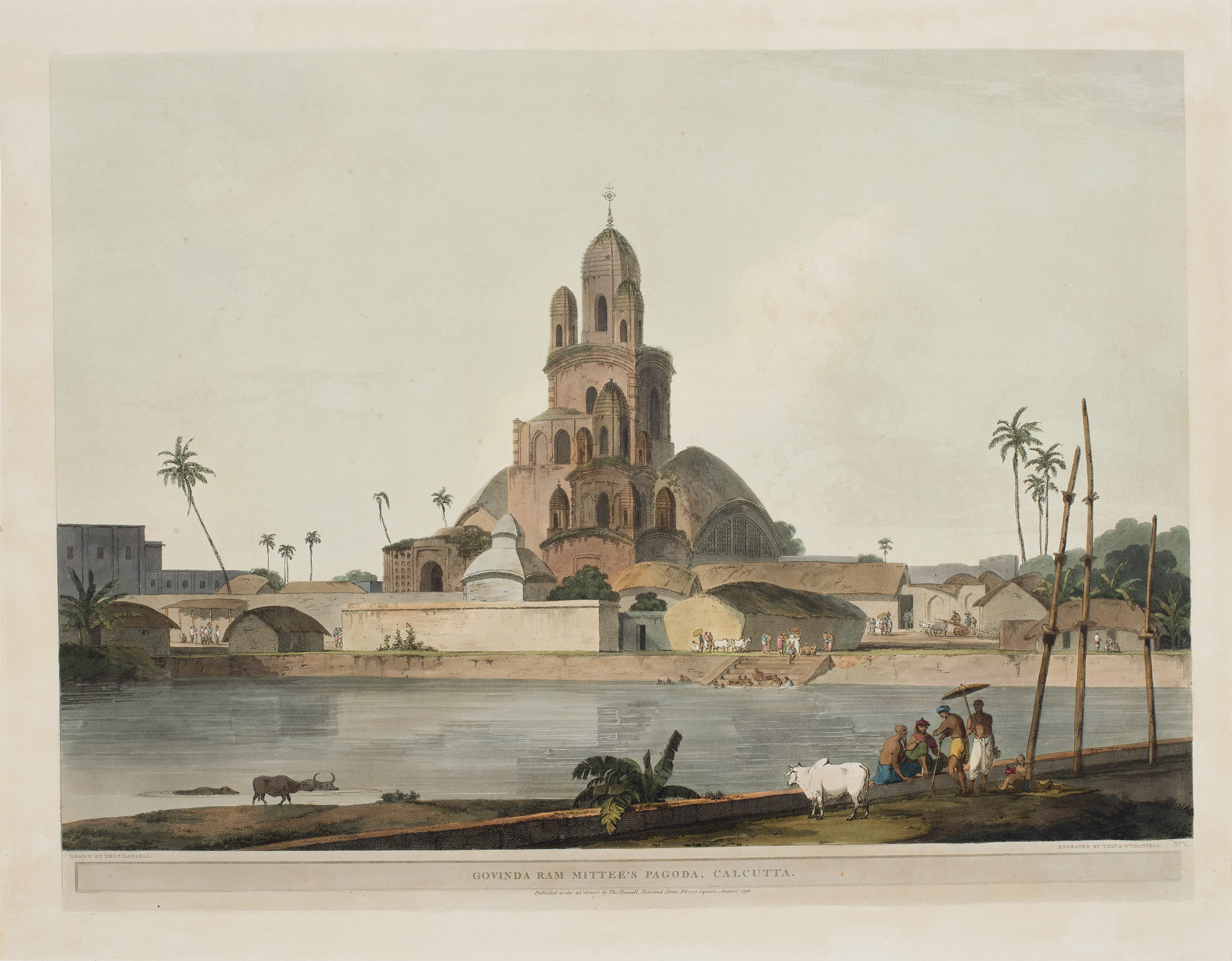

Oriental Scenery The 144 aquatint prints collectively known as Oriental Scenery represent the single largest and most impressive project by English artists to depict Indian architecture and landscape. Thomas Daniell (1749-1840) and his nephew William Daniell (1769-1837) travelled extensively in India between 1786 and 1793. On their return to Britain they produced many paintings, drawings and prints based on the sketches they had made while travelling. The aquatints were issued in pairs between March 1795 and December 1808. Subscribers who purchased all of them were able to assemble them into six volumes, each with 24 prints. They have been arranged in geographical sequence, following the itinerary of their travels. Going through the exhibition, we travel with the Daniells, first from Calcutta, across the Gangetic plain to Delhi; then up into the hills of Garhwal before retracing the route back via Lucknow to Calcutta; then setting out from Madras in a large loop though what is now Tamil Nadu; and finally to Bombay, to explore the rock-cut temples of western India. |

|

Thomas and William Daniell Near the Fort of Currah, on the River Ganges Engraving |

Thomas and William Daniell

View taken on the Esplanade, Calcutta

Engraving

Thomas and William Daniell

The Council House, Calcutta

Engraving

Thomas and William Daniell

Govinda Ram Mittee’s Pagoda, Calcutta

Engraving

Thomas and William Daniell

Siccra Gulley on the Ganges

Engraving

At the beginning of September 1788, the Daniells left the comparative safety and comfort of the Georgian city of Calcutta and embarked in a small boat to sail up the Hooghly towards Murshidabad and the mainstream of the Ganga. They then sailed up-river as far as Kanpur. Along the way they saw their first fine examples of Mughal architecture at Rajmahal, Maner and Allahabad, and both urban and rural riverine views, at Patna, Ramnagar, Sakrigali and Kara. Some of the aquatints from drawings made on this section of their travels bear only Thomas’s name. At this stage, the young William was his uncle’s assistant, not yet the joint artist he was to become. |

Thomas and William Daniell

A Baolee near the Old City of Delhi

Thomas and William Daniell

Hindoo Temples at Brindabund on the River Jumna

Thomas and William Daniell

The Taje Mahal, at Agra

Thomas and William Daniell

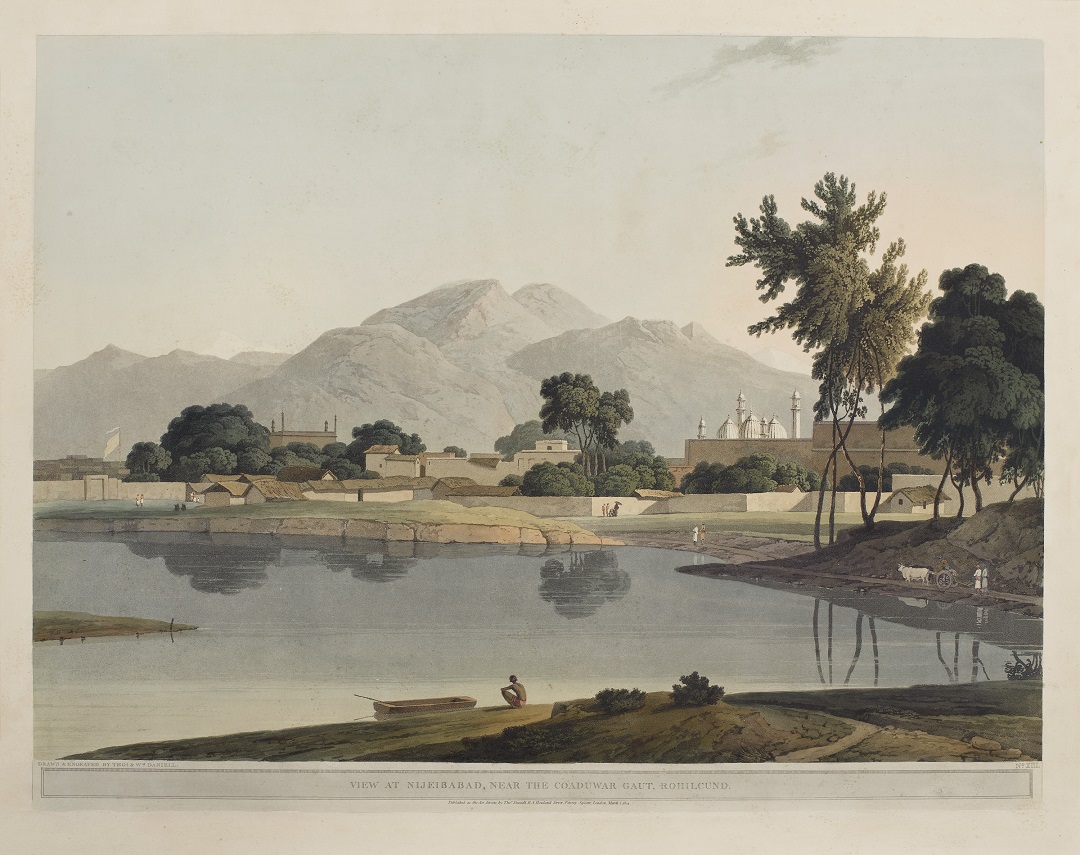

View at Nijeibabad, near the Coaduwar Gaut, Rohilcand

Engraving

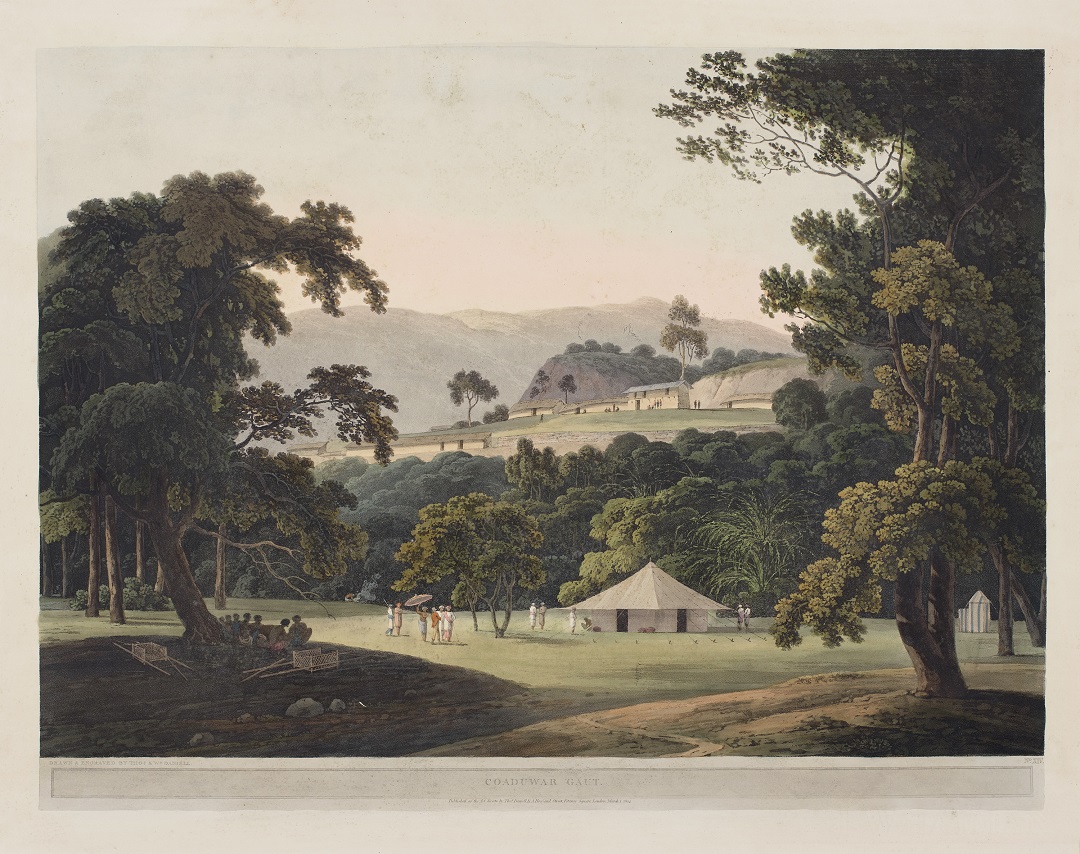

Thomas and William Daniell

Coaduwar Gaut

Engraving

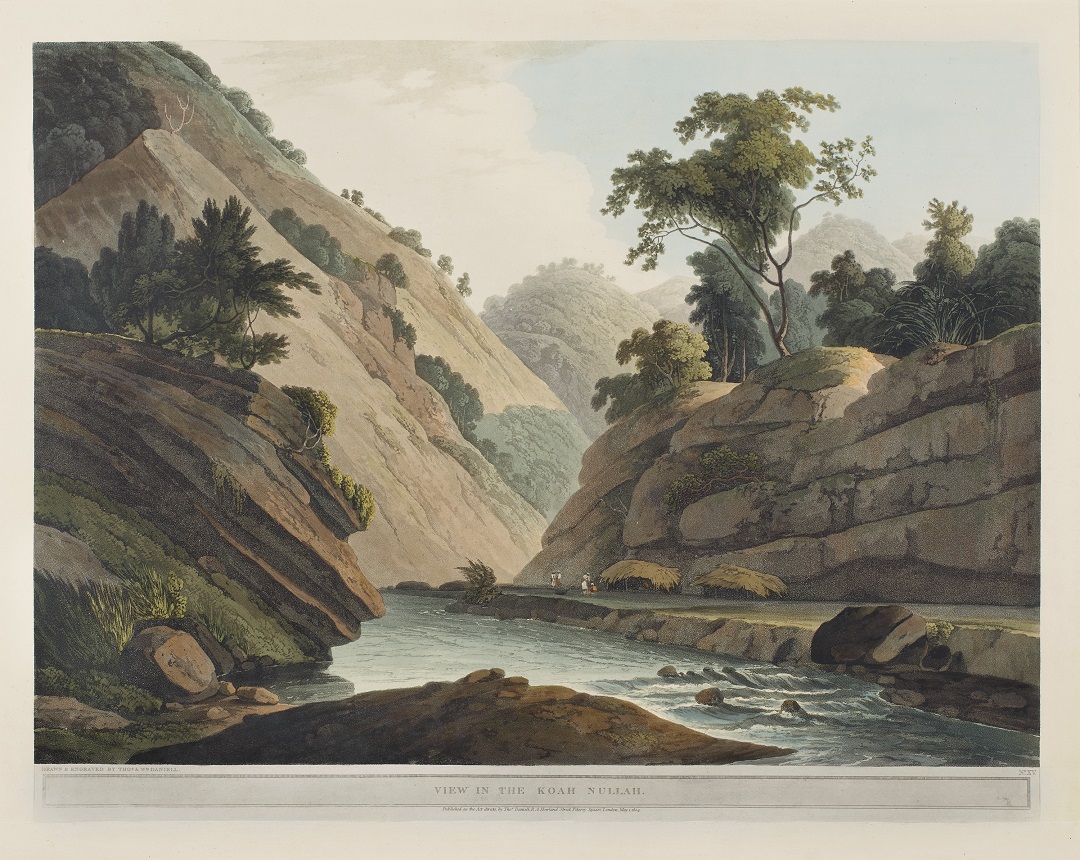

Thomas and William Daniell

View in the Koah Nullah

Engraving

Thomas and William Daniell

Near Dusa, in the Mountains of Sirinagur

Engraving

Leaving Delhi, the Daniells embarked on an expedition into the Garhwal hills, becoming the first Europeans to visit the region. The journey occupied them between mid-March and mid-May of 1789. The twelve views they made in the hills were published in 1804-5 as the second half of Volume IV of Oriental Scenery, which bore the title Twenty-Four Landscapes (the other 12 are views of the south and of the Ganga). As the title suggests, these are among the purest landscape scenes in the series. The Daniells depicted villages but they encountered no grand monuments, and their focus was on hills, rivers and forests. They reached Srinagar in Garhwal just as the Raja was preparing to defend his state from an attack by neighbouring Kumaon, but no sign of this conflict appears in their quiet and peaceful images. |

Thomas and William Daniell

Gate of a Mosque built by Hafiz Ramut, Pillibeat

Thomas and William Daniell

Cannoge on the River Ganges

Thomas and William Daniell

Gate of the Loll-Baug at Fyzabad

|

|

|

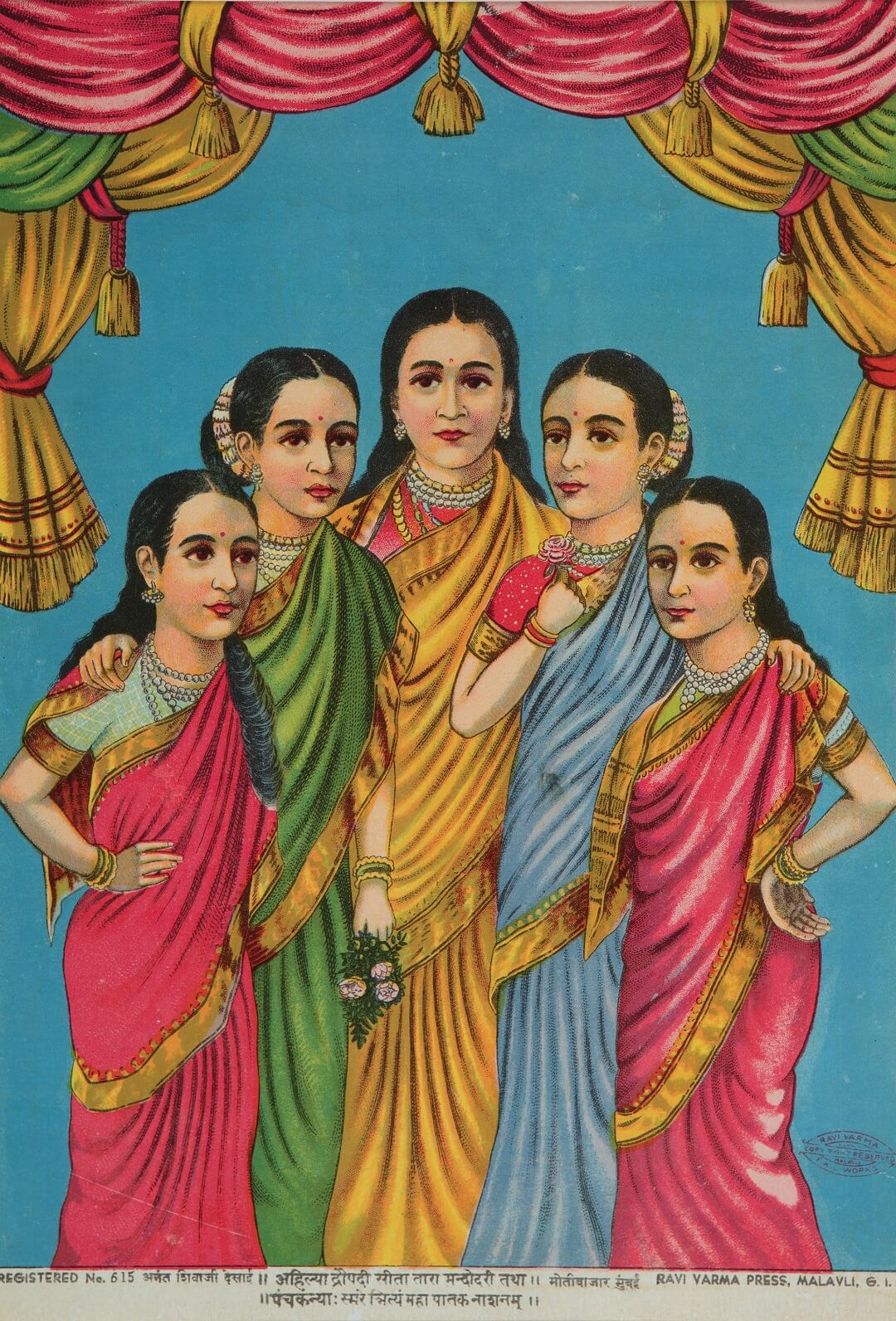

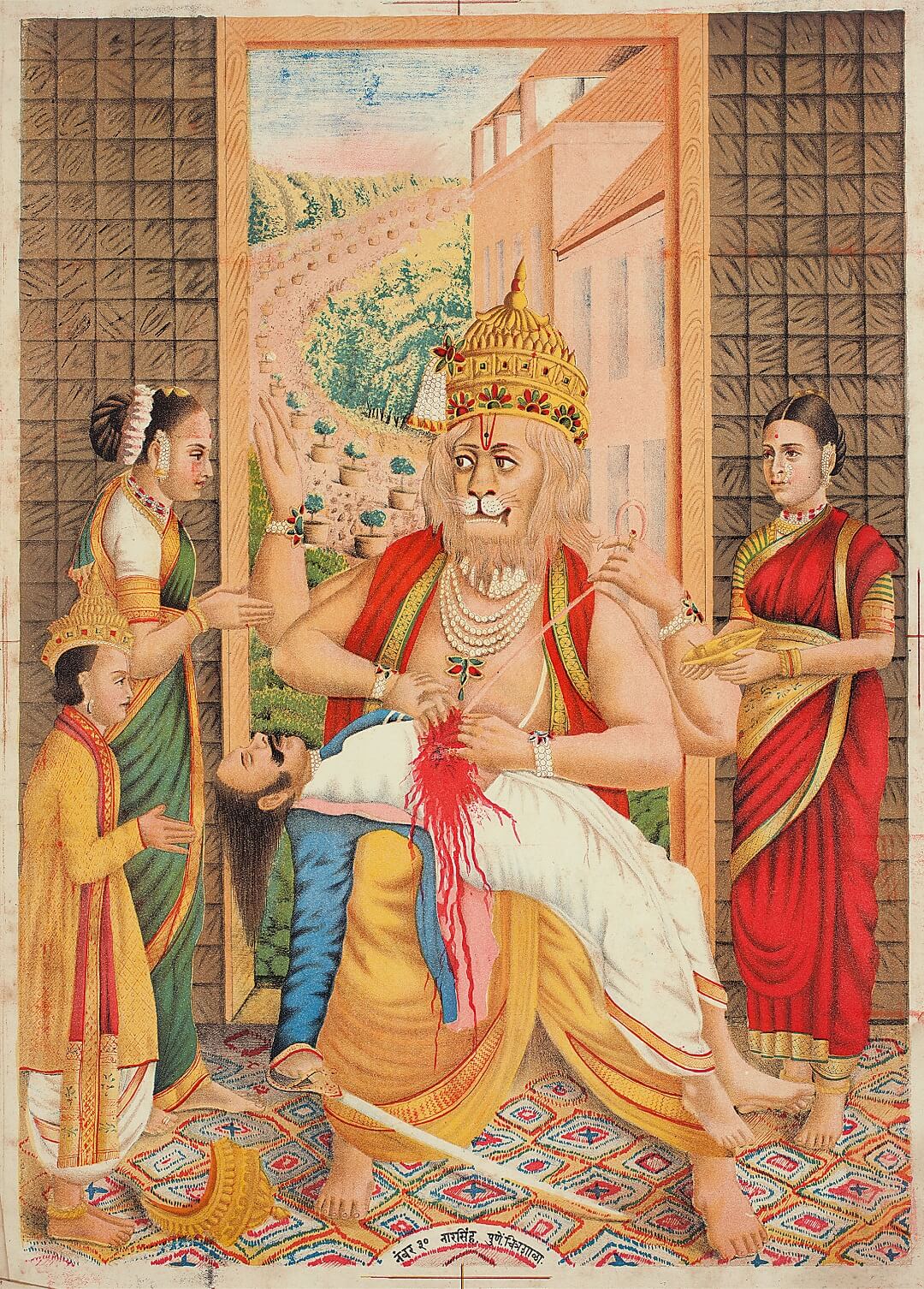

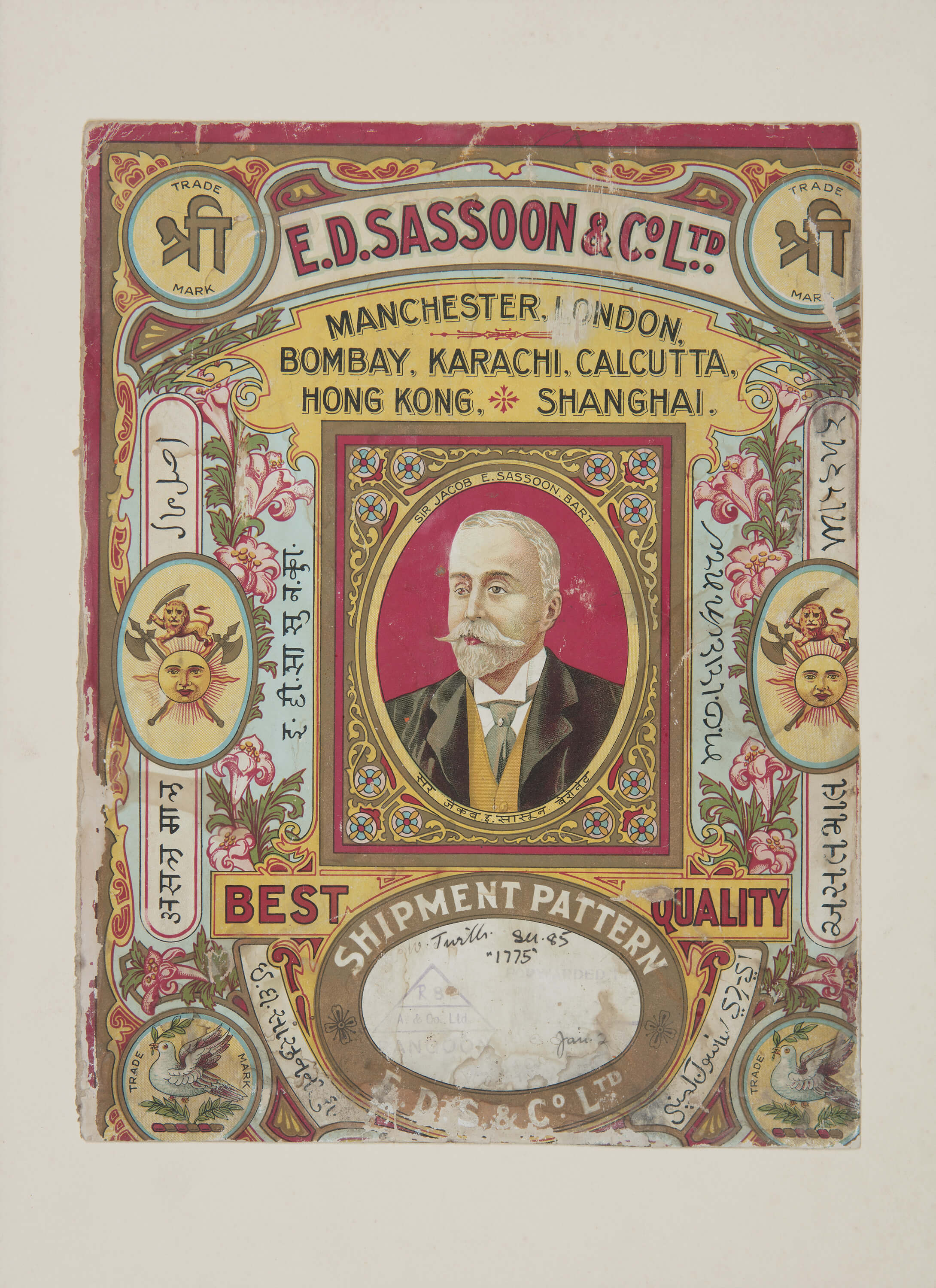

Popular Prints In mid-eighteenth century British India, printing was a flourishing industry. The interest in the ‘Colonies’ led to the presence of European artist-printmakers in the subcontinent and a lucrative trade in printed pictures. With the gradual emergence of an indigenous printing industry, schools of picture-printing in engraving, and, later, lithography, appeared in the bazaars of Calcutta, Delhi, Bombay, Amritsar, Lahore and Mysore. Born of the religious, socio-political and folk influences that characterised life in these metropolises, this late nineteenth century bazaar art was meant for popular circulation. With the advent of industrialisation and the entry of art school graduates into art as a professional enterprise, there appeared a new brand of kitsch in the early twentieth century, spearheaded by the prints of Raja Ravi Varma, Bamapada Banerjee and others. A vast wealth of printed pictures flooded the market, capturing and influencing the popular imagination as the call for independence increasingly gained ground. With the rise of swadeshi, there arose the need to establish a new intellectual and artistic identity. Art now passed into the hands of the reformers of the time, the educated upper middle class and elite. As a part of the national movement, there appeared a new tier of literature meant for the consumption of the educated. Printmaking, or the art of the printed picture, became a tool to illustrate this new brand of nationalist literature. It also came to be used as a means to reproduce paintings made by the emerging orientalist artists of the time, leading to wider dissemination of an emerging nationalist ideal for popular imagination to subscribe to. |

|

Anonymous The Fort of Agra Metal engraving |

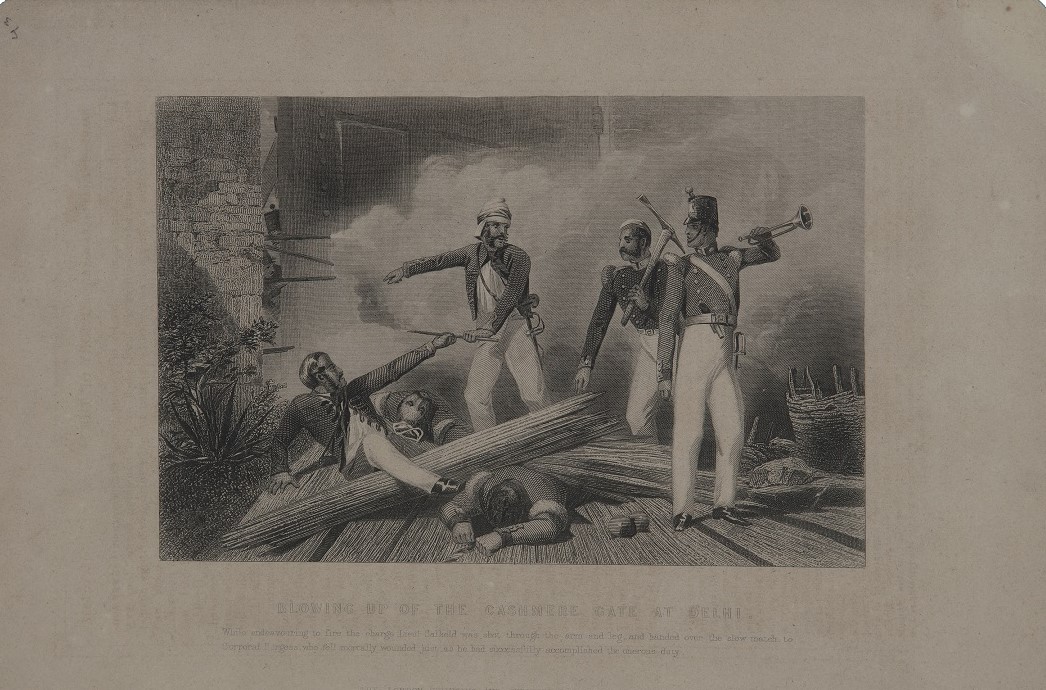

Anonymous

Blowing up of the Cashmere gate at Delhi

Etching and aquatint on paper

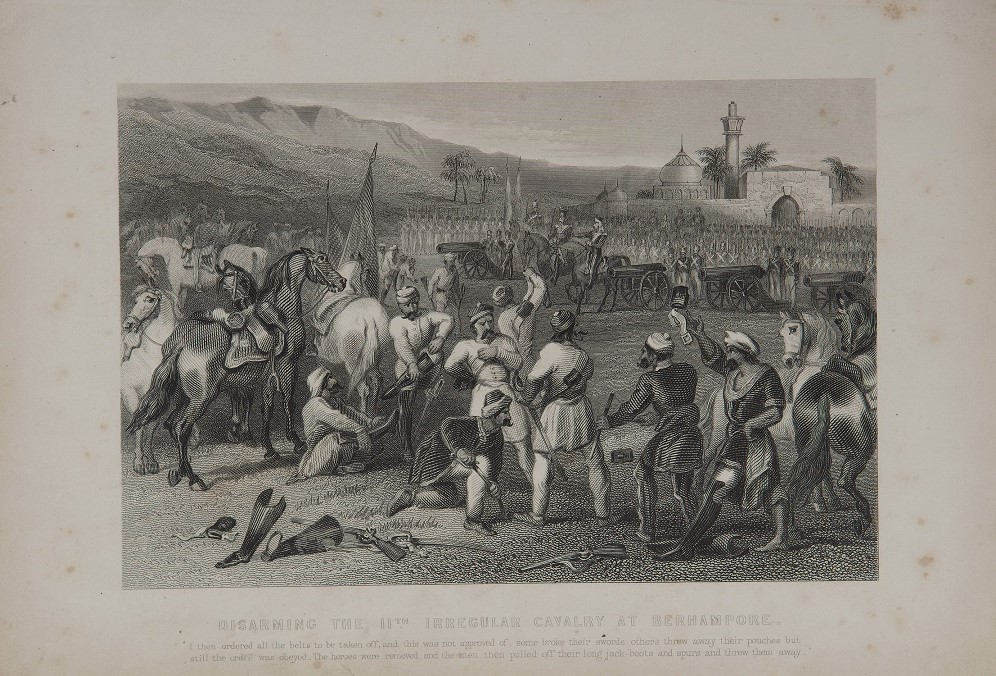

Anonymous

Disarming the 11th irregular cavalry at Behrampore

Etching and aquatint on paper

Anonymous

Repelling a Sortie before Delhi

Etching and aquatint on paper

The Sepoy Mutiny was a widespread but unsuccessful rebellion against British rule in India in 1857-58. Begun in Meerut by Indian troops in the service of the British East India Company, it spread to Delhi, Agra, Kanpur, and Lucknow. The ferocity of both mutineers and British officers in quelling rebellion comprise tales that fired many an imagination. Depicted here are a series of intaglio prints by a British artist illustrating various aspects of the uprising as it spread like wildfire eastwards towards Bengal. Governance by the East India Company was henceforth abolished in favour of the British Crown. |

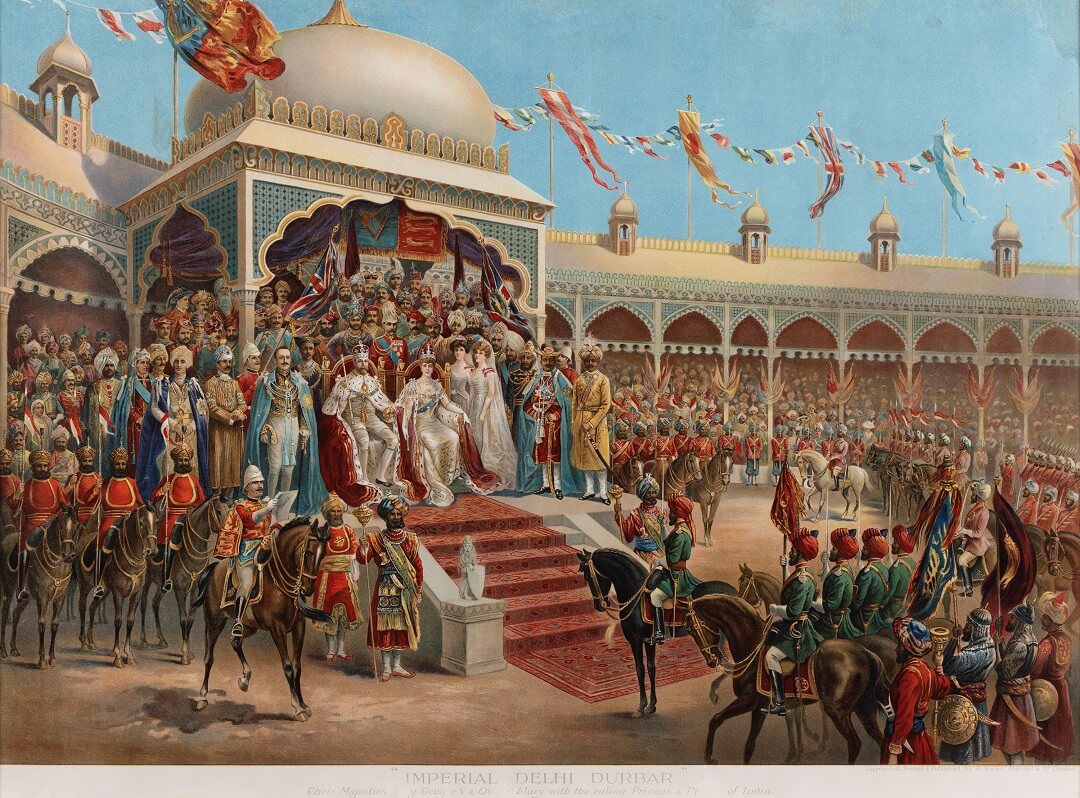

Anonymous

H. M. King George V and His Gracious Consort, Queen Mary

Anonymous

Imperial Delhi Durbar

Anonymous

Queen Victoria

Anonymous

Untitled

In 1858, the governance of India was vested directly in the British Crown in the person of Queen Victoria. After being formally declared Empress of India in the Delhi Durbar of 1877, numerous chromolithographs of the Queen as the supreme symbol of authority and benevolence came into public circulation. The Emperor and Empress of India, along with the royal family, adorned everything from chromolithographic advertising labels to broadsheets, capturing the popular public imagination.

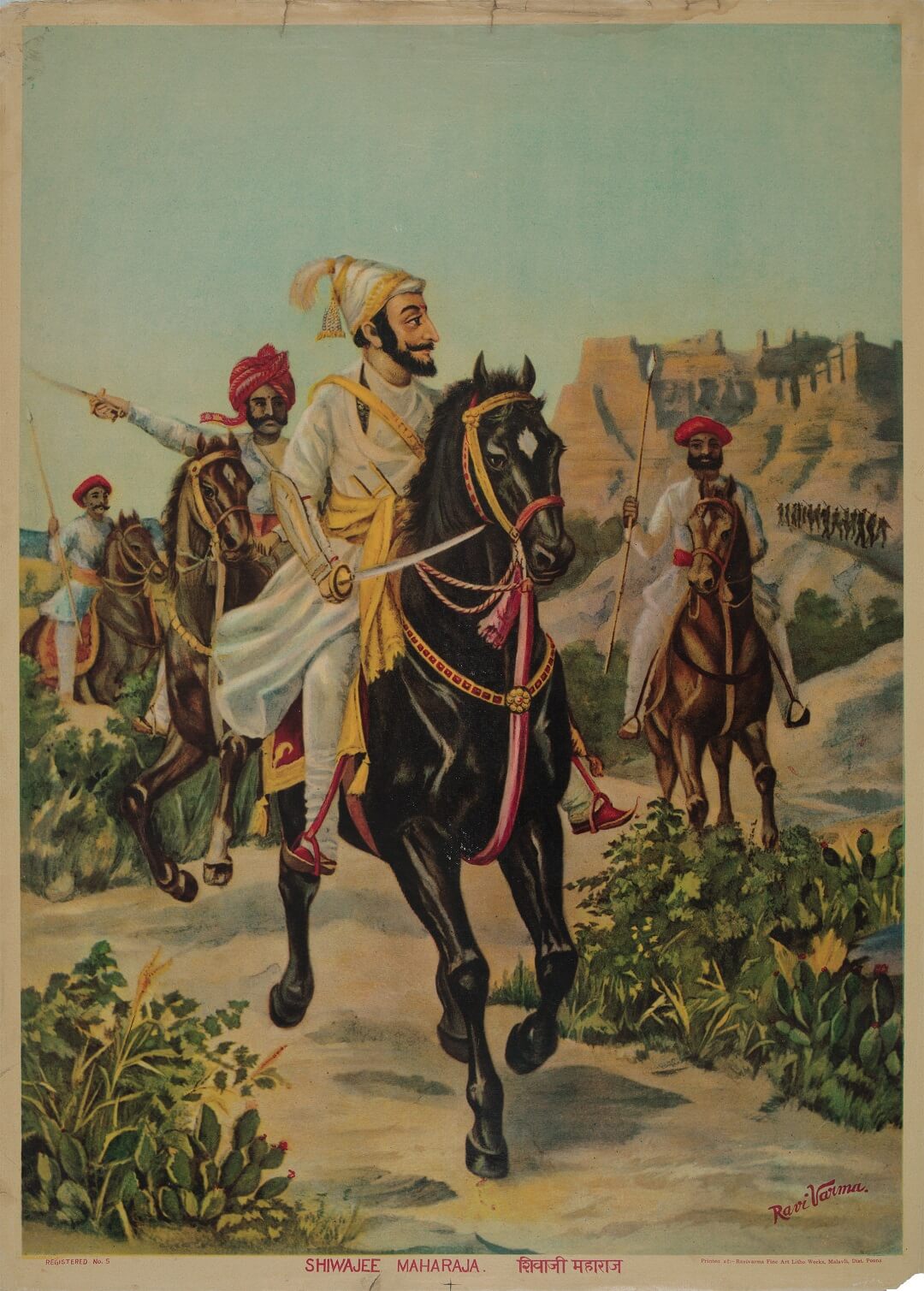

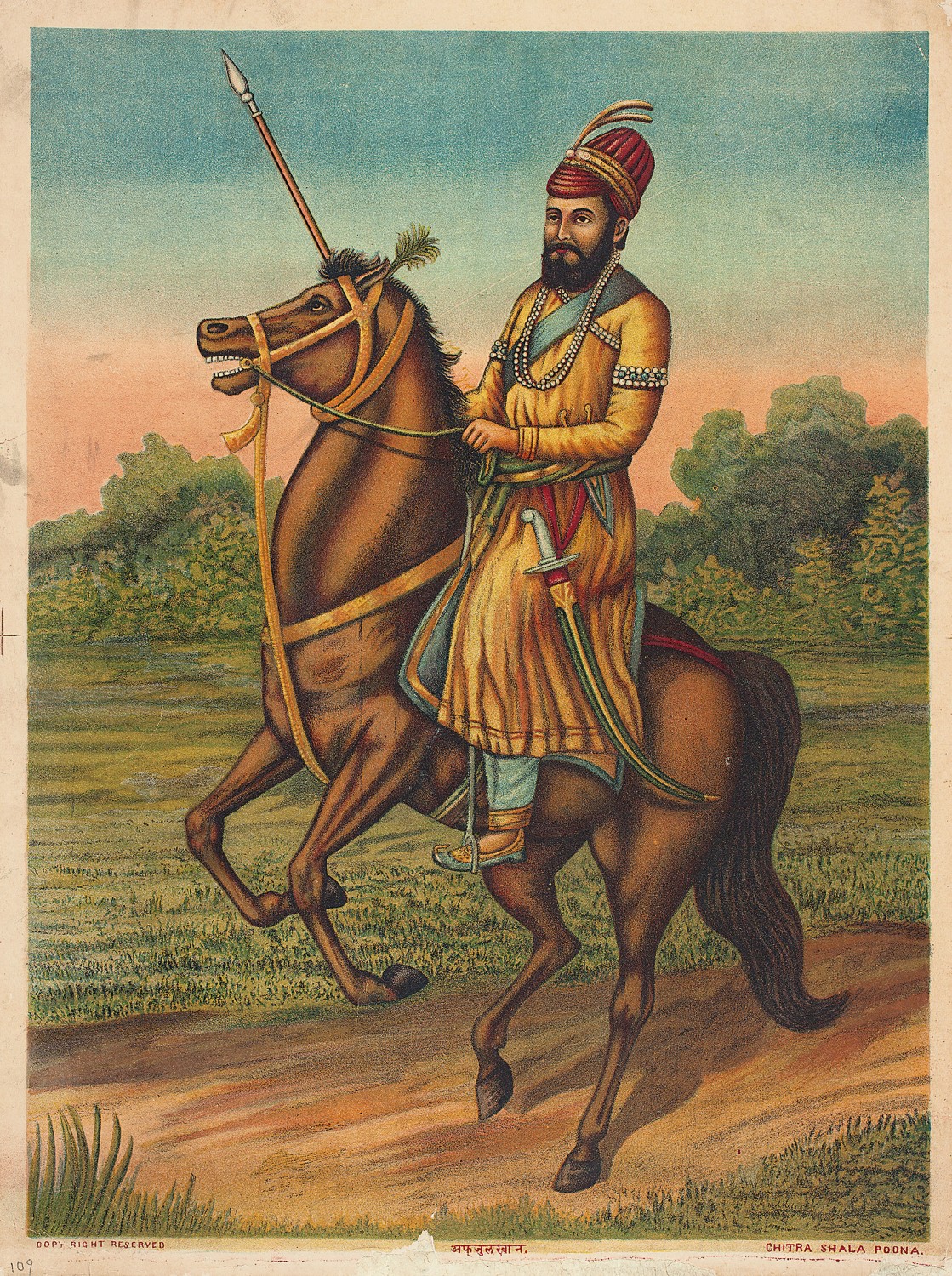

Anonymous

Shiwajee Maharaja

Anonymous

Afzul Khan

H. H. Shri Bhagvatsinhjee Bahadur

H. H. Shri Bhagvatsinhjee Bahadur

Anonymous

Nana Fadnavis

Portraits of the rulers of these princely states, fashioned on British royal portraiture, became popular subjects of rendition in the sprouting nineteenth century indigenous printing presses, alongside warrior heroes of yore such as Chhatrapati Shivaji, ready to ride into battle. As the call for independence gained ground, these portraits served to arouse the patriotic fervour of the people.

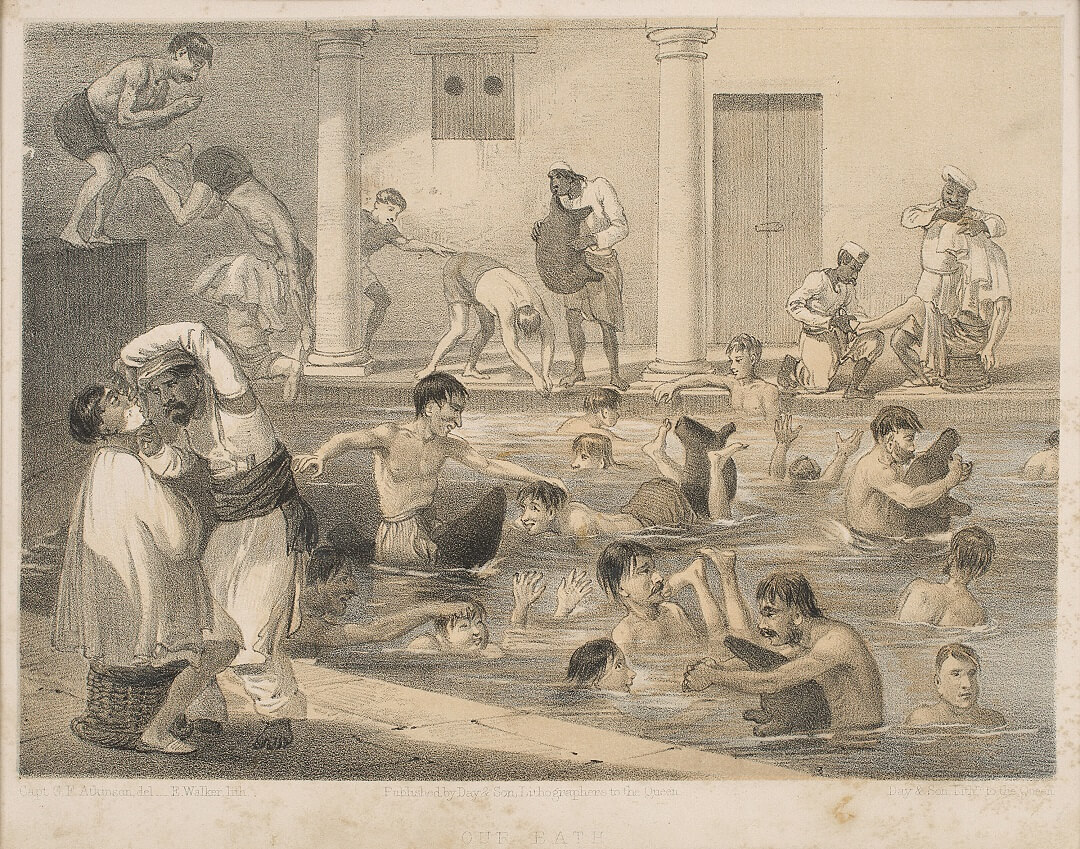

Anonymous

Our Bath

Hand-tinted lithograph on paper

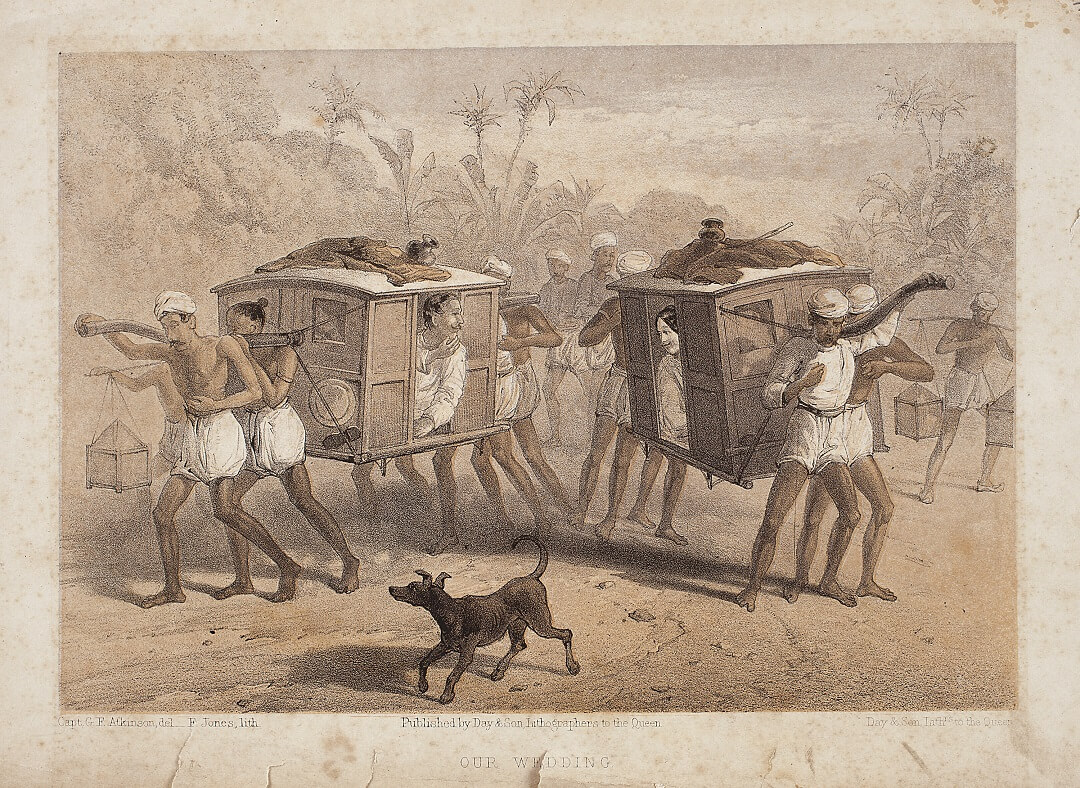

Anonymous

Our Wedding

Chromolithograph on paper

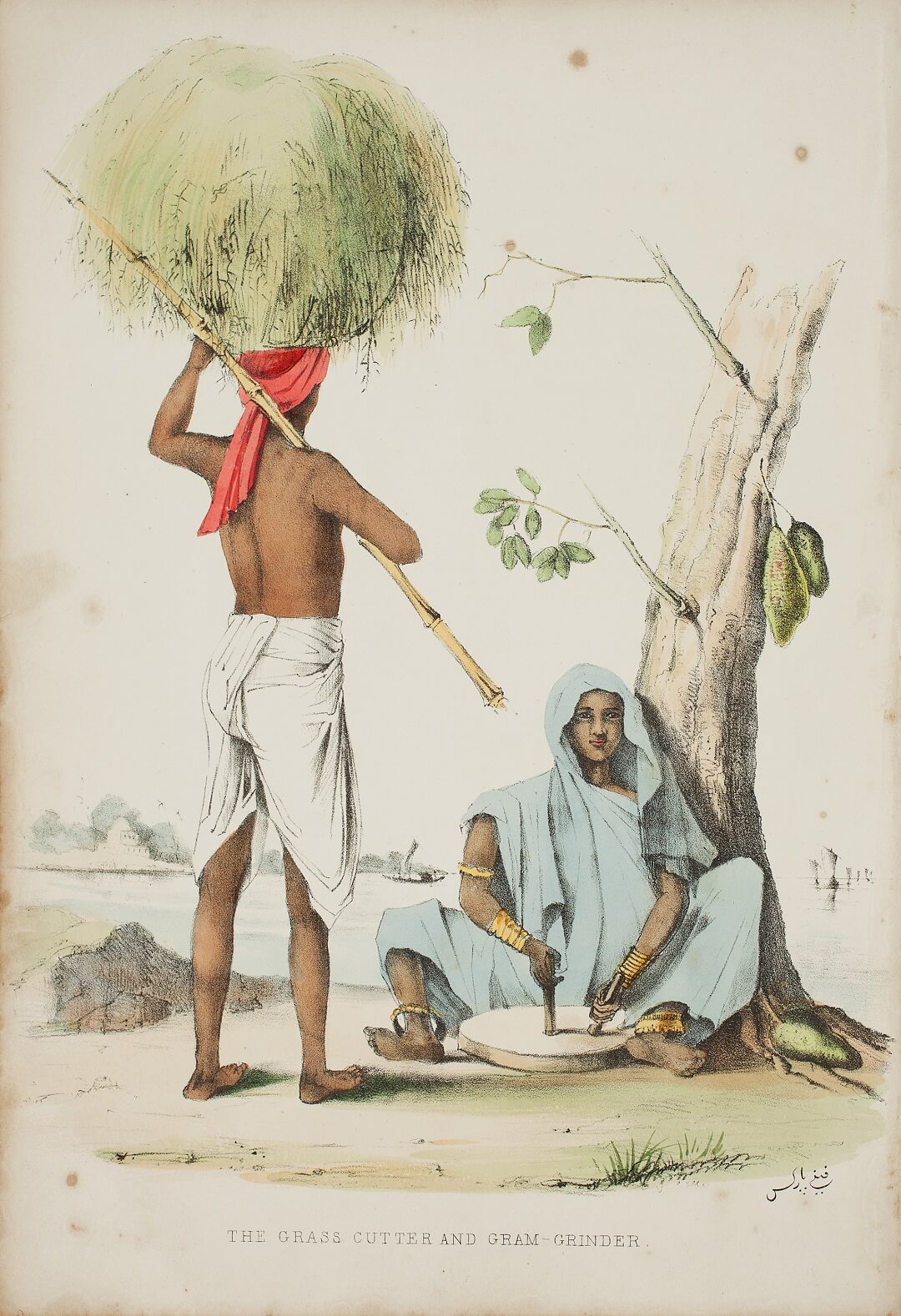

Anonymous

The Grass Cutter and Gram Grinder

Chromolithograph on paper

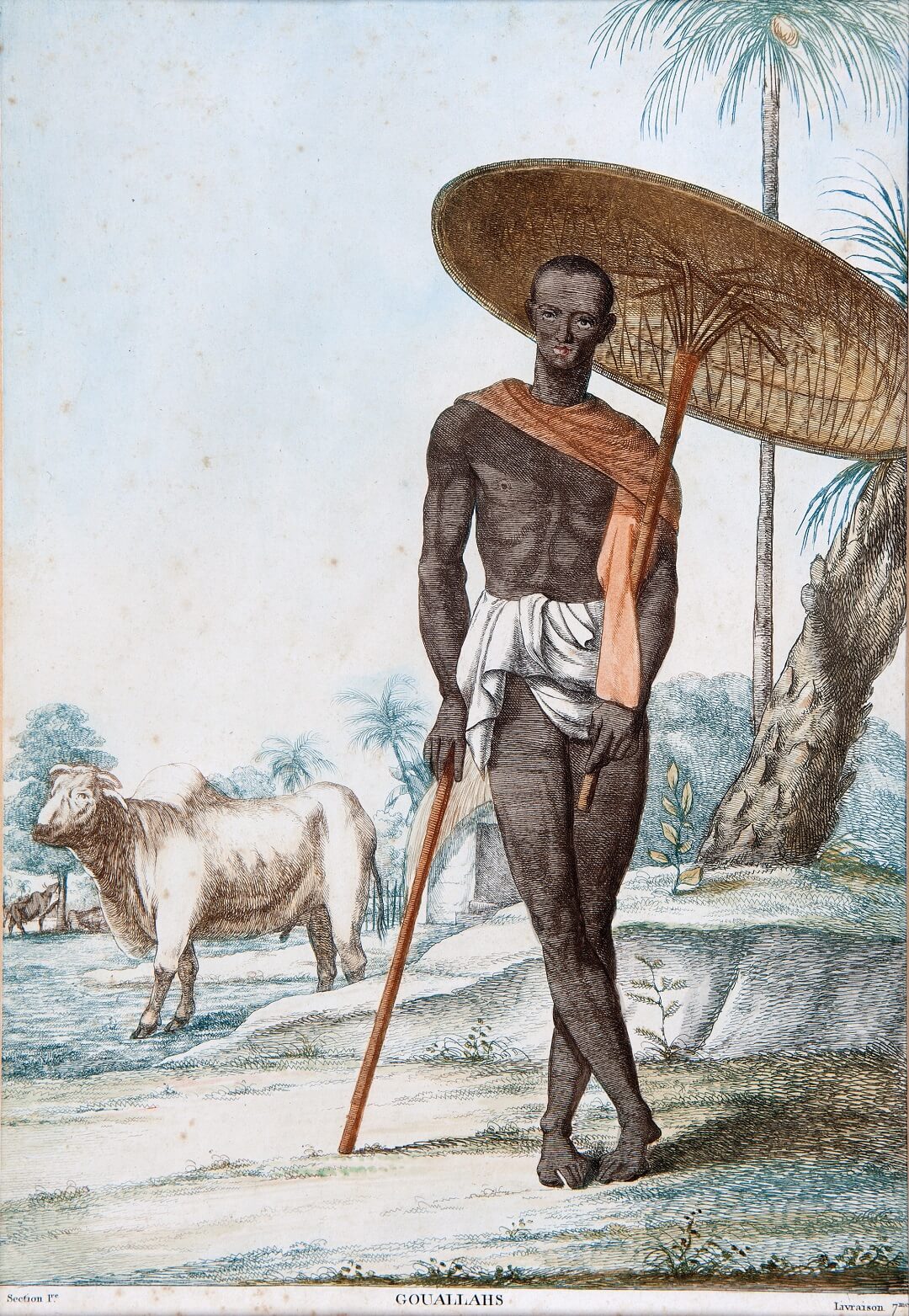

F.B Solvyns

Gouallahs

Hand-tinted etching

The heyday of artistic activity among British artists in India coincided with the golden age of engraving and lithography in eighteenth and nineteenth century Europe. With the industrial revolution, British attitudes underwent a change, evincing a lively curiosity in the people, trades, culture, flora and fauna of a land little known to the West, a land that significantly contributed with its skills and manpower to the revolution. The ‘picturesque’ qualities of the Indian scene led to an enthusiastic number of amateur and professional European artists in India documenting the subcontinent for consumers back home. In the era preceding photography, the drawings and watercolours made by these intrepid artists were reproduced as book and advertising illustrations, and display prints, mostly by printing and publishing houses in Europe. |

Anonymous

Untitled

Anonymous

Narsingh

Anonymous

Untitled

Anonymous

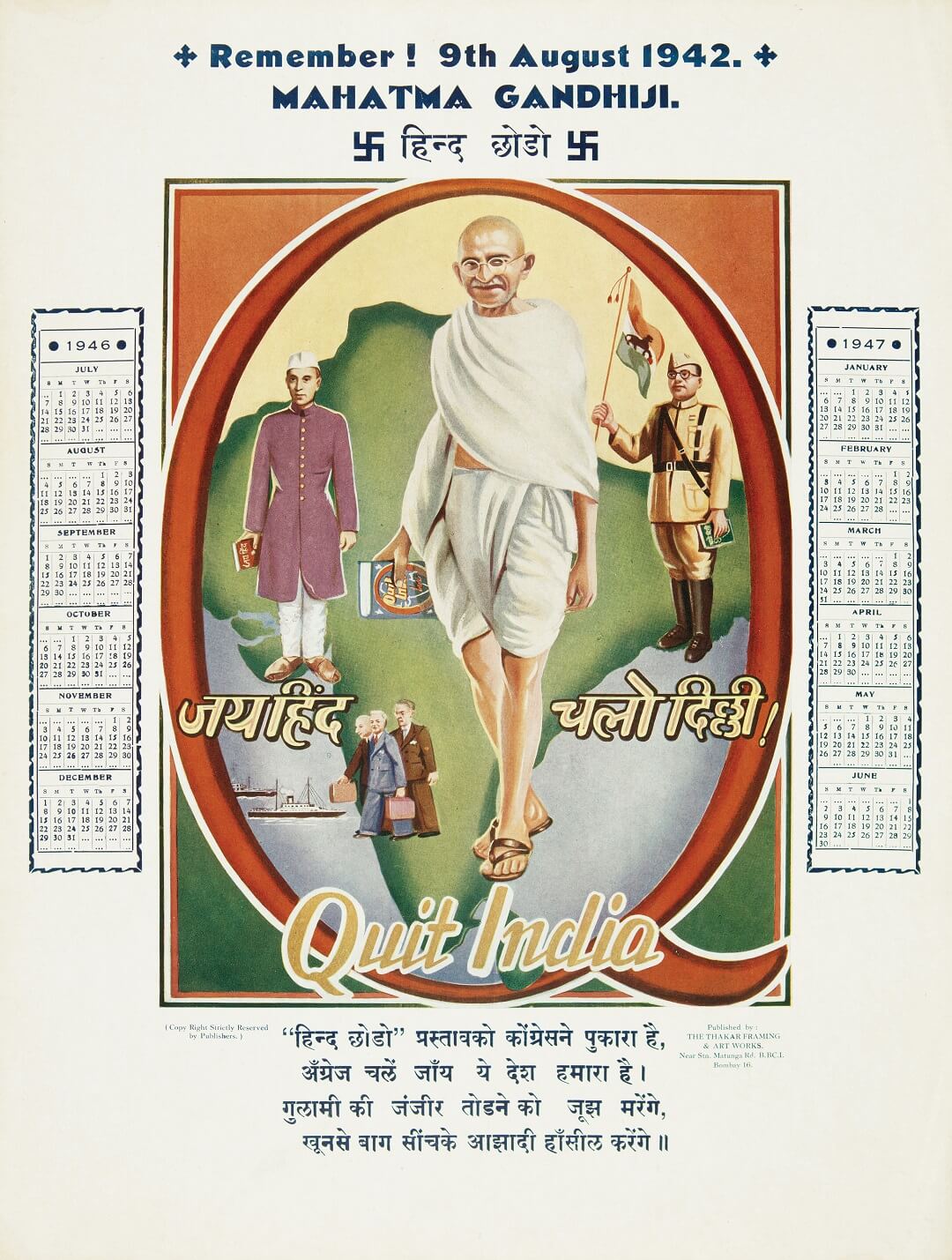

Remember! 9th August 1942. Mahatma Gandhiji. Hind Chodo

Indigenous advertising illustrations, calendar pictures et cetera formed a vast wealth of printed images that were initially produced by planographic processes, and later in the half-tone process. Since these were utilitarian in nature and occupied zones of daily use such as shops, offices and homes, these illustrations had much wider reach and impact as compared to the broadsheet. Some of these illustrations also advertised Indian enterprise and contribution to industry, synonymous with the emergence of a new Indian identity.

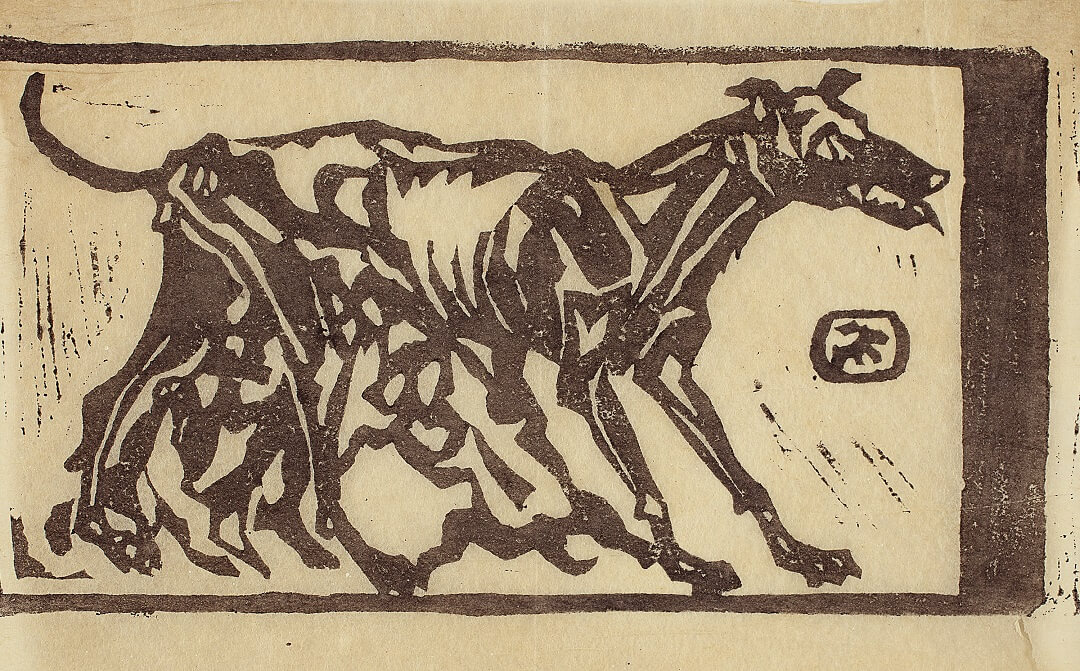

Nandalal Bose

Untitled

Woodcut rice on paper

Rani Dey

Untitled

Woodcut on newsprint paper

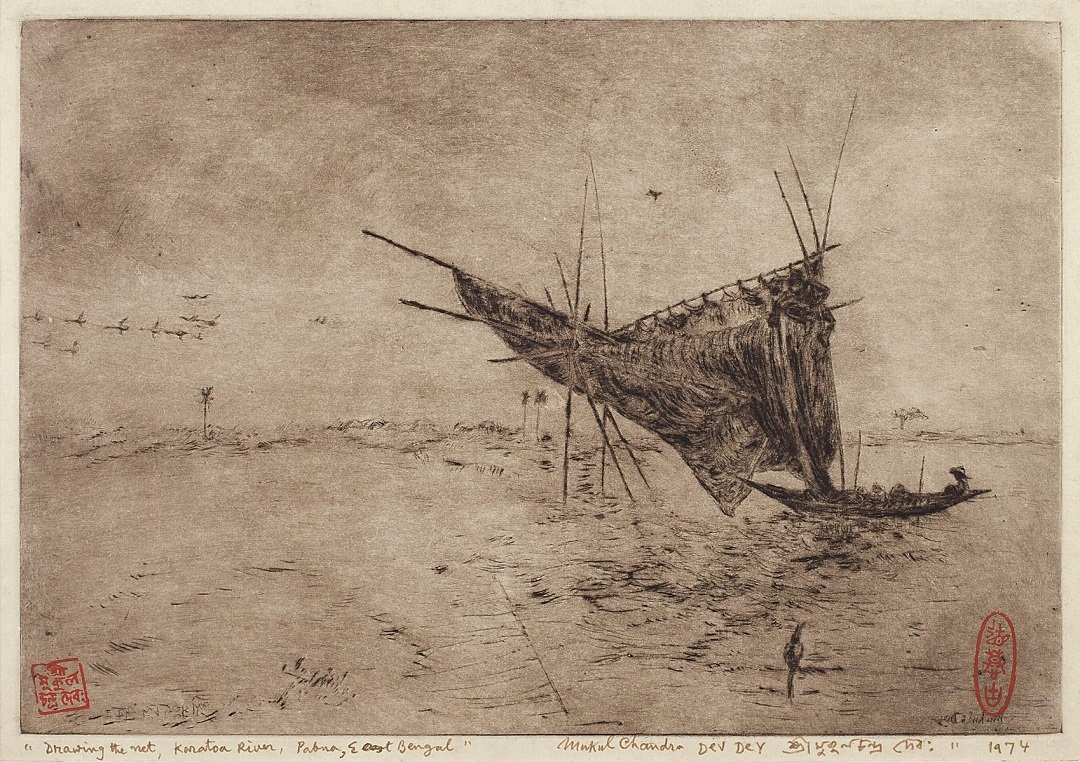

Mukul Dey

Drawing the Net, Karatoa River, Pabna, East Bengal

Drypoint on paper

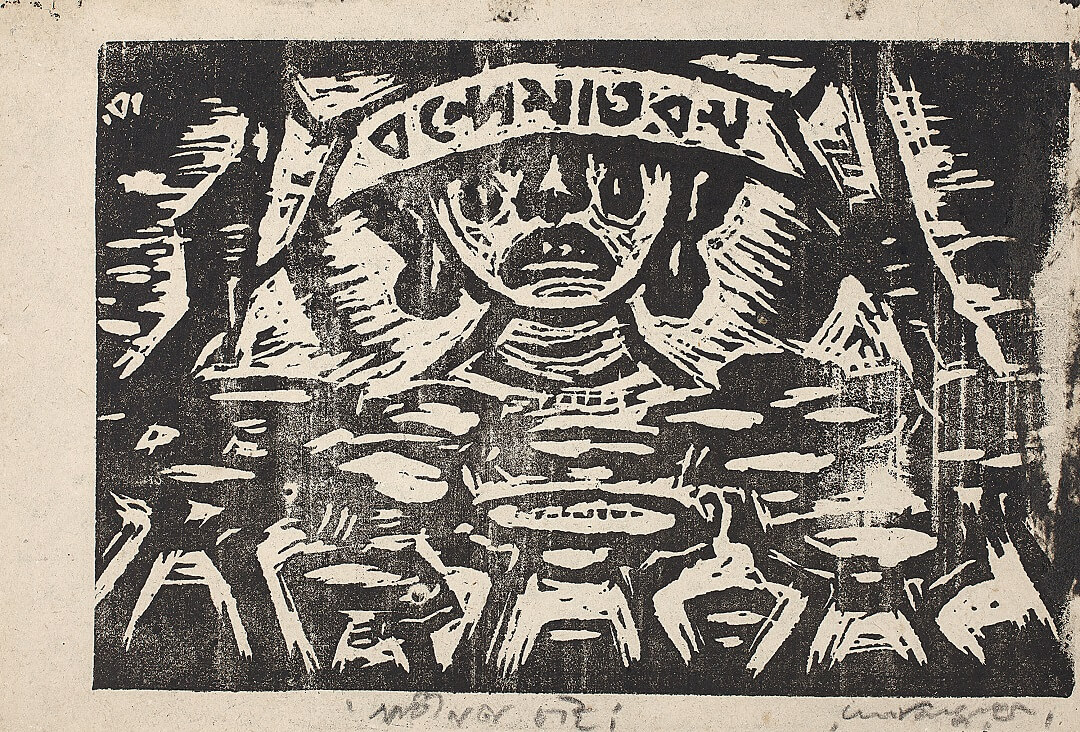

Ramkinkar Baij

Swadhinta Chaii

Woodcut

Against the rising fervour of the Swadeshi movement and paradigm shifts in artistic thought, printmaking as a fine art emerged, marked by Gaganendranath Tagore’s publication of three cartoon albums between 1917-21. In the early 1920s, Rabindranath Tagore founded his university, Visva-Bharati, at Santiniketan. In 1920-21, Nandalal Bose assumed the reigns as principal of Kala Bhavana there. Bose soon introduced printmaking to the curriculum, gradually spearheading a movement in the medium from Santiniketan. Together with his students, namely Ramkinkar Baij, Benode Behari Mukherjee, Surendranath Kar, Lalit Mohan Sen, Ramendranath Chakravarty, and many others, Bose effected new ways of seeing Indian life and landscape, radically different from the inclination to exoticise seen thus far. |

|

Portrait of our People This exhibition captures a seldom noticed twin trajectory of a political and artistic movement in India’s recent history. The backdrop of the Uprising of 1857 heralded a major moment in the struggle for freedom, and less than a century later in 1947, India’s Independence was achieved. Coinciding with this extraordinary journey was an older order giving way to a new reality, and an ancient civilization that was making its way into the modern world. And as artists traversed the length and breadth of India, they were to encounter her multitudes in the inner landscapes of their individual visions. Their process of representation was to soon coalesce with new ideas, techniques and technologies as this modern zeitgeist was to energize and awaken the genre of portraits like everything else in their worlds. The challenge to capture a microcosm of this panoply of people and characters is not an easy gauntlet but a necessary moment. As we look back upon the slow weaning away of tradition with the excitement that technology brought, the camera and its lens were to allow for visual exactitude in a manner that had hitherto frustrated artists. While for many, a way to rival the photograph was to adopt its tropes and or to add colour to prove the superiority of the brush; others hovered around the immediacy of reality and nurtured newer genres and styles spurred on by global artistic movements. And amidst all of this was the hapless sitter, whose fate was being decided by the artists who sought to consign him or her to posterity. And here today, in pen and ink, paint and canvas, print and paper and all manner of art, we seek to understand a portrait of our people and the remarkable times they lived through. |

|

Kisory Roy Art and Famine Oil on canvas |

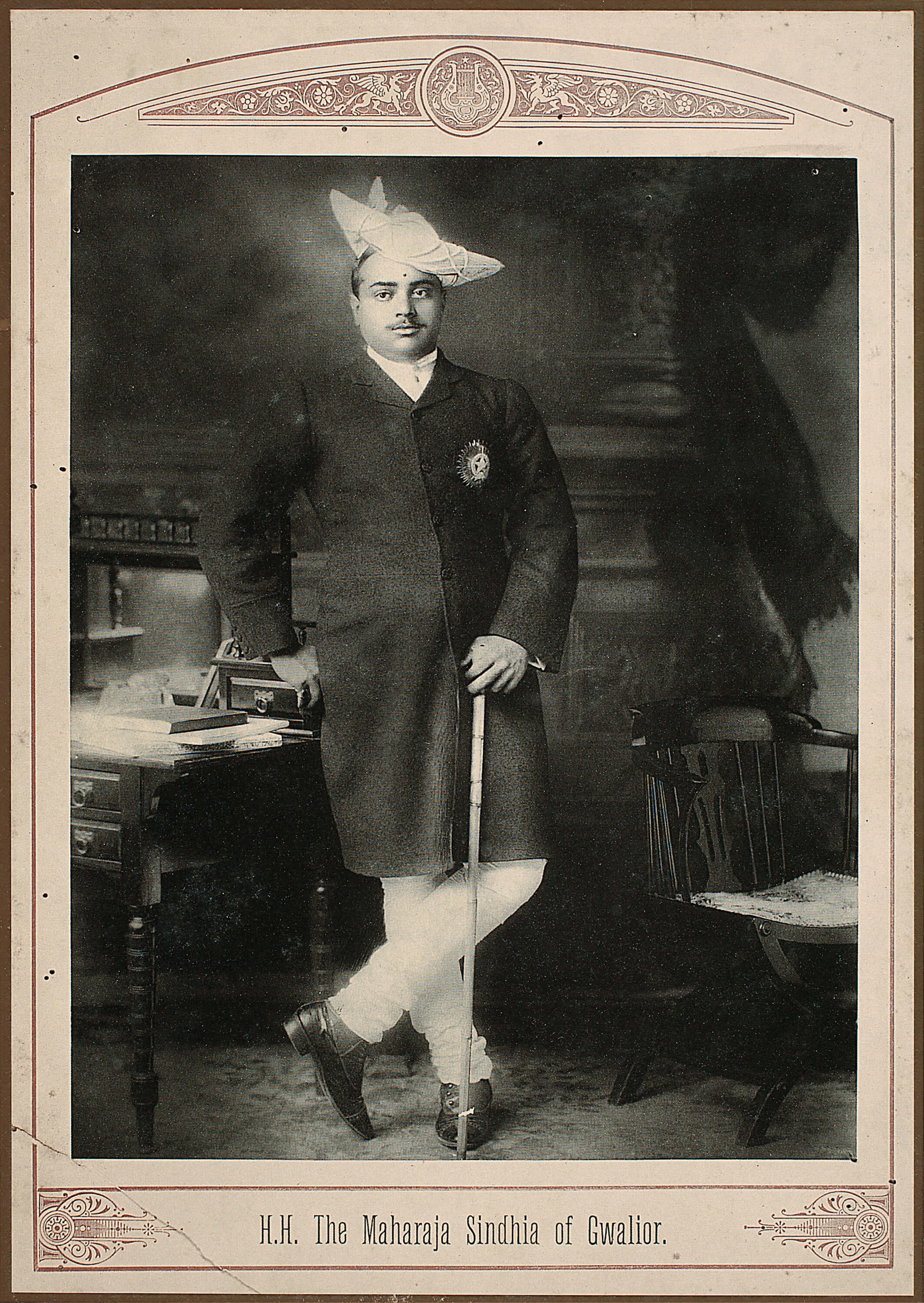

Anonymous

H. H. The Maharaja Madhorao Sindhia (1876-1925) of Gwalior

Mechanical print on paper

Anonymous

H. H. Jam Sahib Jaswantsinhji Vibhaji Jadeja (1882-1906) of Navanagar

Mechanical print on paper

Anonymous

H. H. Maharaja Jagatjit Singh (1872-1949) of Kapurthala

Mechanical print on paper

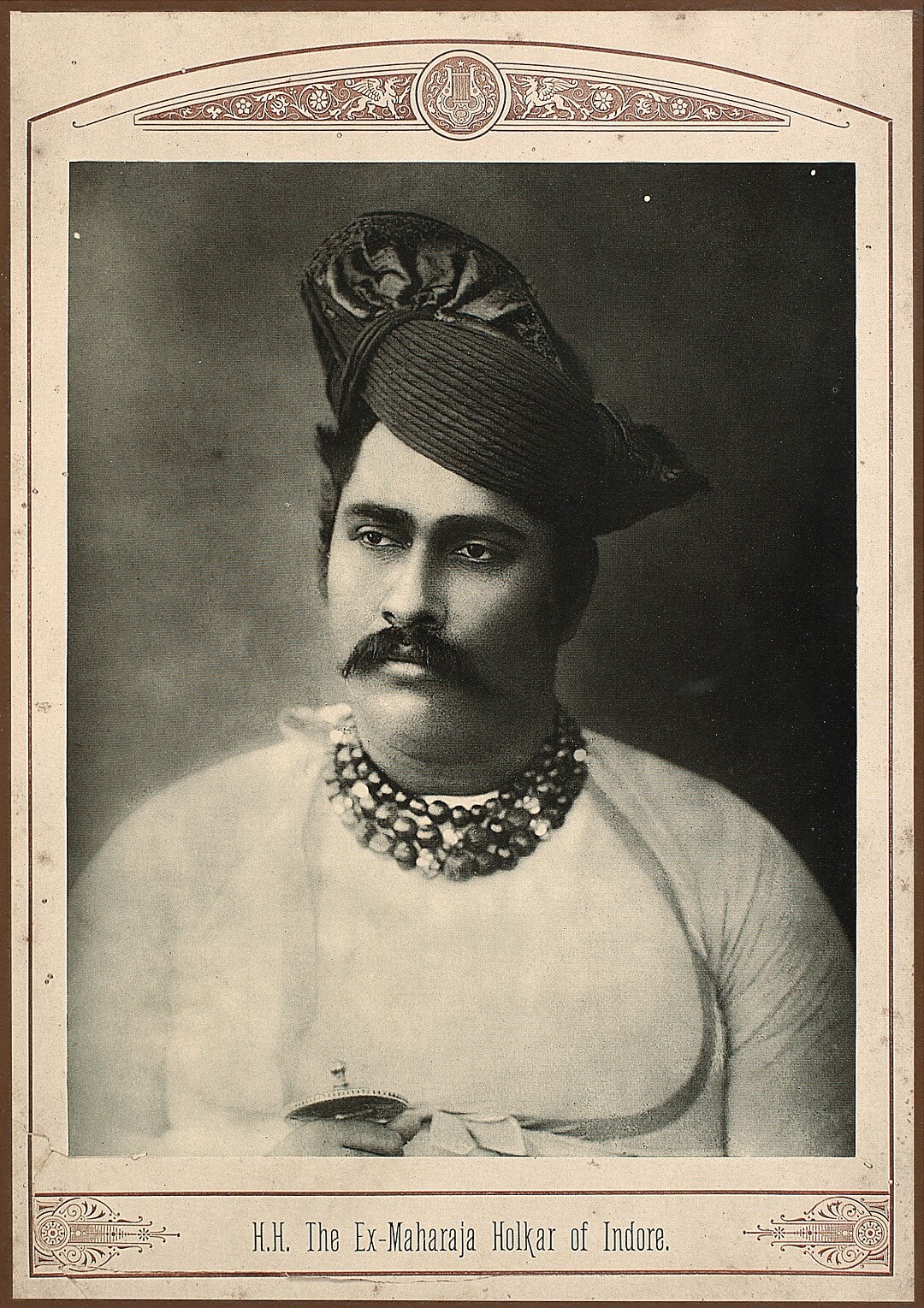

Anonymous

H. H. Maharaja Shivajirao Holkar (1859-1908) of Indore

Mechanical print on paper

The camera is recorded as having reached Indian shores by 1840 at Calcutta (Kolkata), the then capital of the Raj. The medium almost immediately found patronage amongst rulers of Princely states both independent states and those under the Raj. In most instances however, it was to spell a death knell for traditional portrait painters. A proliferation of building activities across Princely India with the creation of new palaces and public buildings meant that photographic images were reproduced in large numbers. Several copies of these images, oftentimes autographed were also gifted as a sign of favour and proximity to courtiers, friends and family. However, by the third quarter of the 19th century, photo studios were to create portfolios of rulers from across India, that could be commissioned or purchased. A further level of dissemination occurred when these images were produced at much affordable prices by using photomechanical devices. Now reduced to the equivalent of posters or calendar art, they were to find quick currency amongst a much wider audience. |

Anonymous

Maharaja Vikram Deo V (1869-1951) of Jepore, Orissa

J. Barton

King Edward VII

Anonymous

Two Young Girls

Anonymous

Nawab Mohammad Ali Khan Bahadur (1881-1947) of Malerkotla, Punjab

The more intrepid among artists were to soon sense an opportunity when they realized that the camera could only capture people and places in black and white. This was to launch an important new phase of painting in India where painters gave new life to photographs by tinting in colour. These ranged from subtle hued portraits favoured by several rulers, to others where the application of colour and line was to completely obliterate the original photograph and render its use purely as an under drawing.

Sudhir Khastgir

Untitled

Oil on board

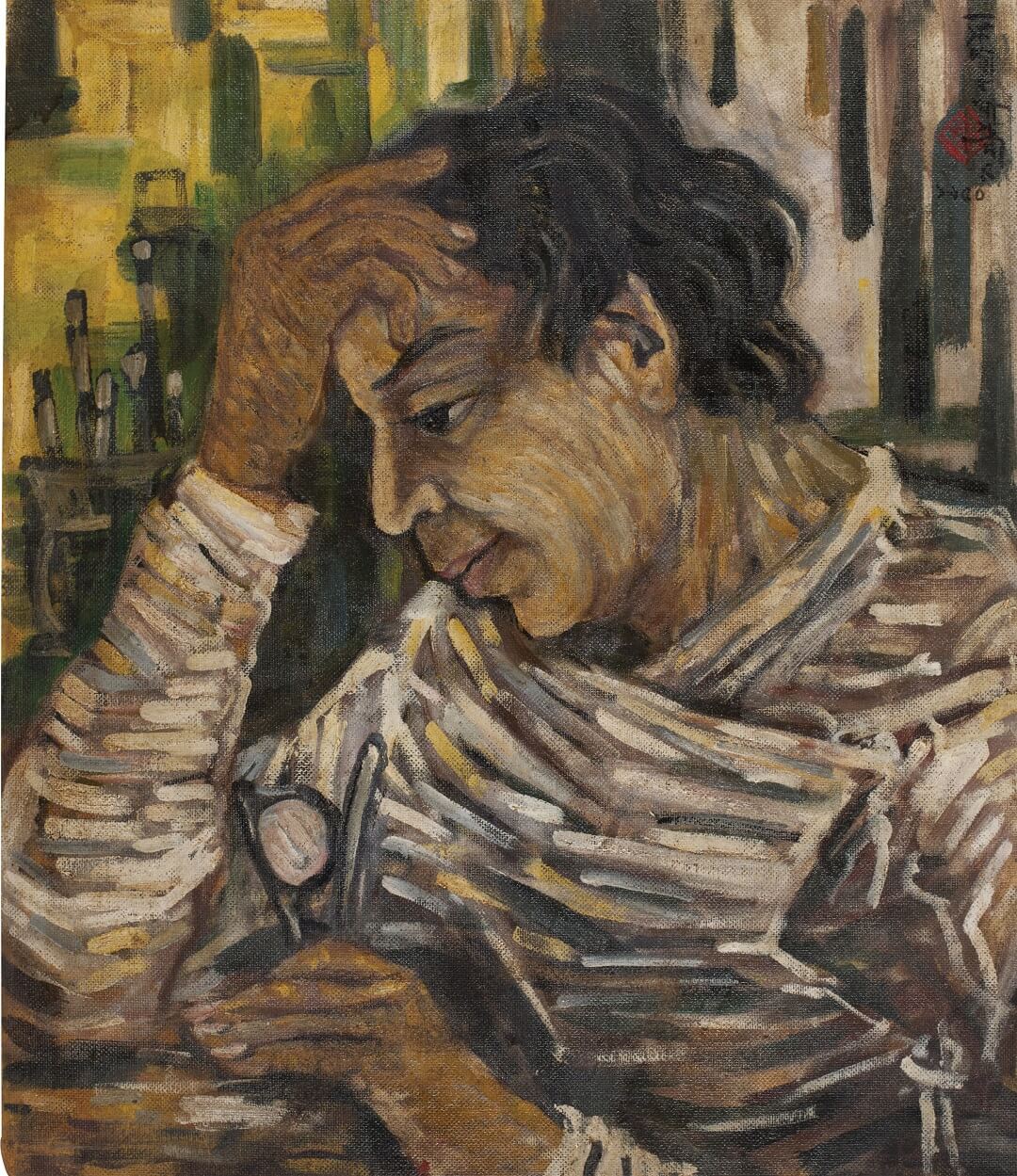

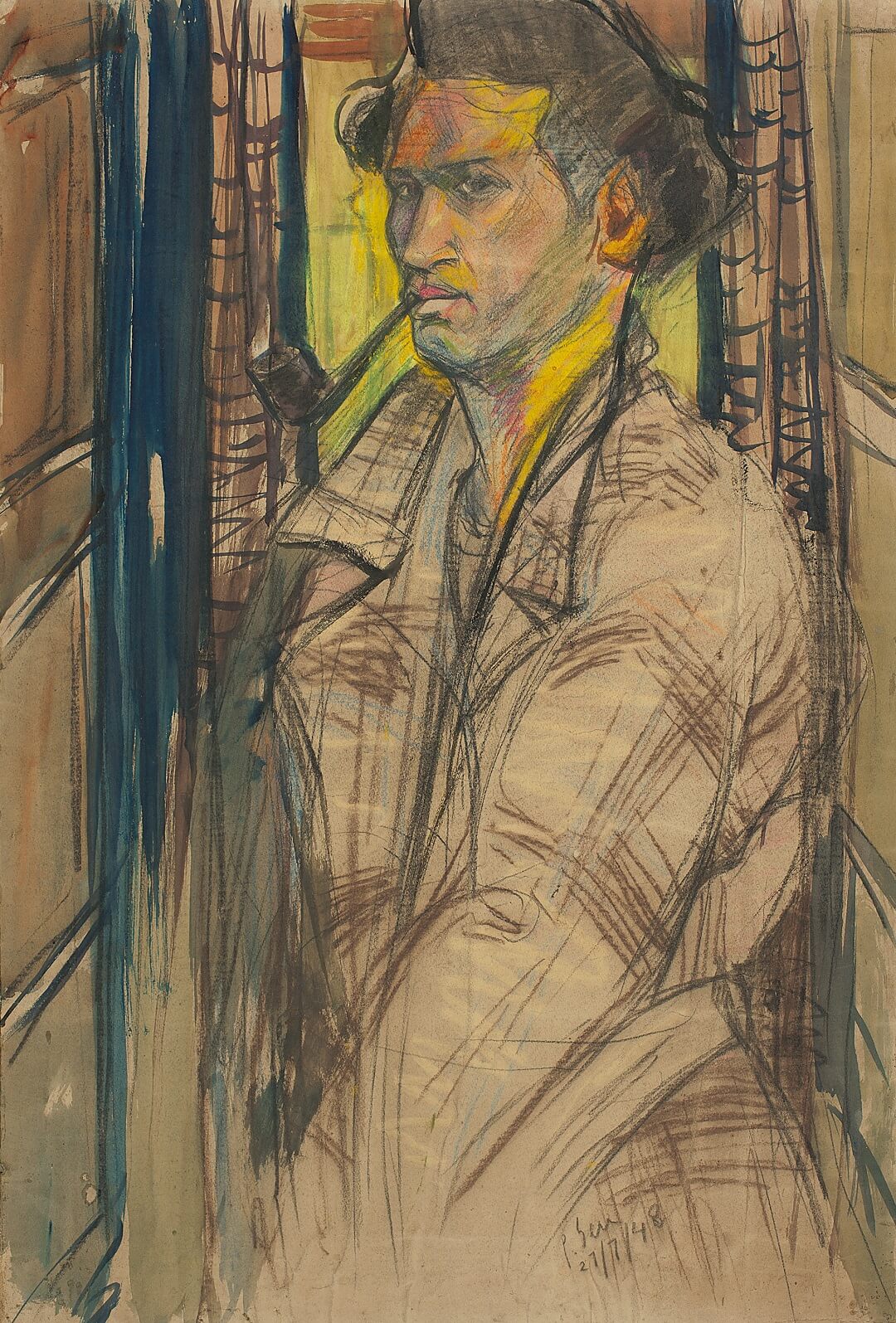

Paritosh Sen

Self-Portrait

Water colour, ink, conte and pastel on newsprint paper

Pestonji Bomanji

Self Portrait

Oil on board

M.V. Dhurandhar

Portrait of Mrs. Dhurandhar

Oil on canvas

The last decades of the 19th century were to see a shift in the agency of creation decisively away from patrons and to the hands of artists. Discussions about the subconscious, of symbolism and an ability to see sitters through multiple filters, away from academic realism and other established practices was to herald in the new genre of Modernism. Individual characteristics were highlighted, with the sitter frequently captured unguarded and in candid moments far removed from posturing. In the first half of the twentieth century as India’s independence movement was reaching a crescendo, the struggles of individuals spearheading the movement was to percolate across the country. A rare dynamism, movement and an immediacy in connection with the portrait was now contrasted with the stillness of the figure. Everything was sacrosanct while nothing was sacred. |

M.F. Pithawalla

Unidentified Parsi Lady

M.F Pithawalla

Unidentified Parsi Lady

Anonymous

Unidentified Parsi Matriarch

M.F. Pithawalla

Unidentified Parsi Gentleman

Anonymous

Rani Sahiba of Bedag State

Anonymous

Maharani Vani Vilasa of Mysore

Anonymous

Raja Vasudeva Raja Avargal of Kollengode, Kerala

The existence of a small group of paintings depicting rulers and their extended family from the mid twentieth century displays a curious amalgam of miniature painting techniques applied to photographic realism. This strange hybrid created by skilled artists saw great adherence to detail especially in the recreation of jewels and court costumes, however the near photographic quality of human representation devoid of any background detail was to render a surreal touch to the combined finished product.

EXHIBITION VIEWUnderstandably, historians and art critics alike have always seen the Fort as something beyond its yearly appearance on the television screen. An antiquity that more than anything else should be restored to the public, so it can say much more than is already assumed about the structure built during Shah Jahan’s reign. Therefore, after spending years restoring several barracks within the fort, The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) has opened the multistorey barracks to the public. Of these, barrack no. 4, in collaboration with DAG, will offer a unique visual history of India through its art titled Drishyakala. ‘India’s art and history come together through four exhibitions at the Red Fort in Delhi,’ FirstPost, 23 February, 2019 |

In association with