Drawn with Love: When Artists Write to Children

Drawn with Love: When Artists Write to Children

Drawn with Love: When Artists Write to Children

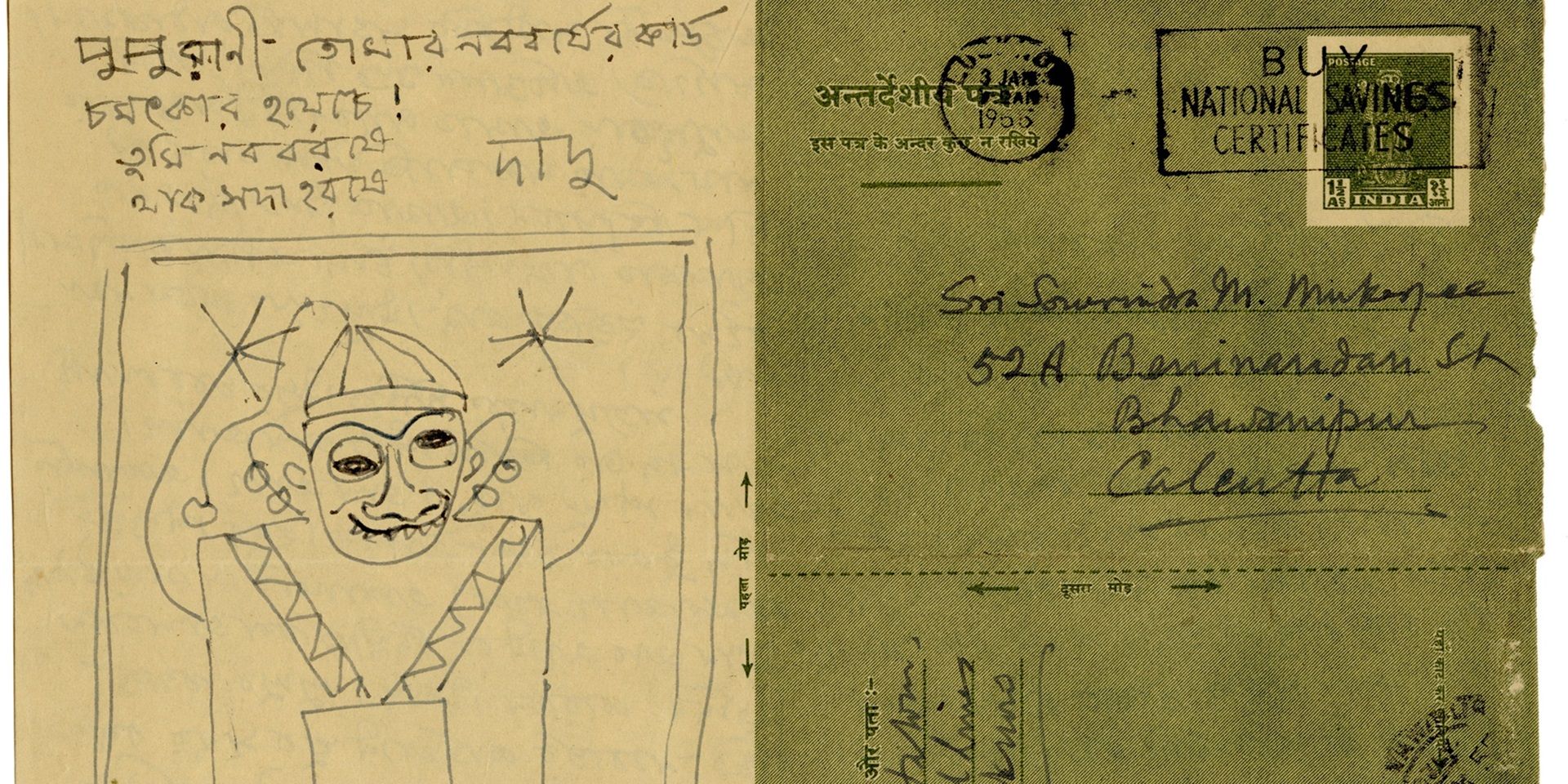

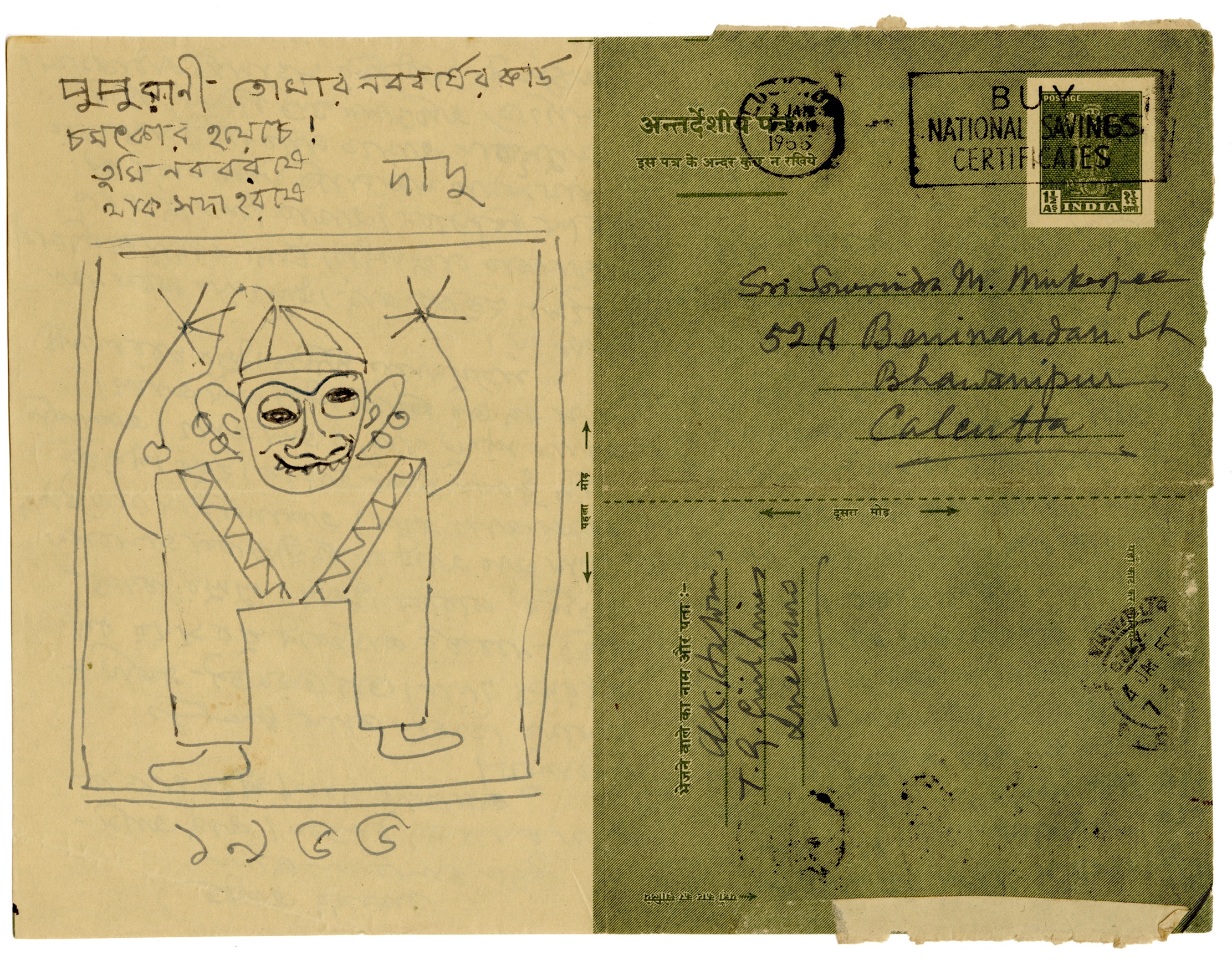

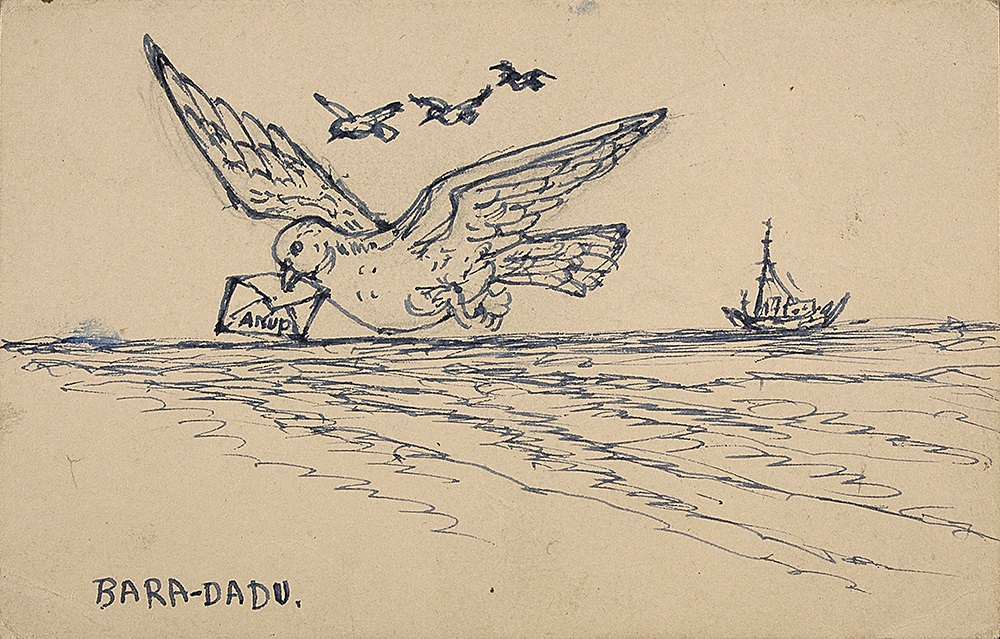

Asit Kumar Halder, Handwritten inland letter (detail), 1955, 7.5 x 10.2 in. Collection: DAG Archive

In an era characterised by instant communication through mobile applications, the anticipation and joy once associated with receiving handwritten letters from loved ones have largely diminished. This sense of loss becomes even more poignant when the sender is an artist—whose letters might contain not only carefully chosen words, but also original drawings and verses composed especially for the recipient.

For artists, fitting an illustration into the confines of a letter or envelope can be a stimulating artistic brief. It allows them to explore the relationship between artwork and the letter’s physical form, sometimes including small objects or decorations that enrich the correspondence.

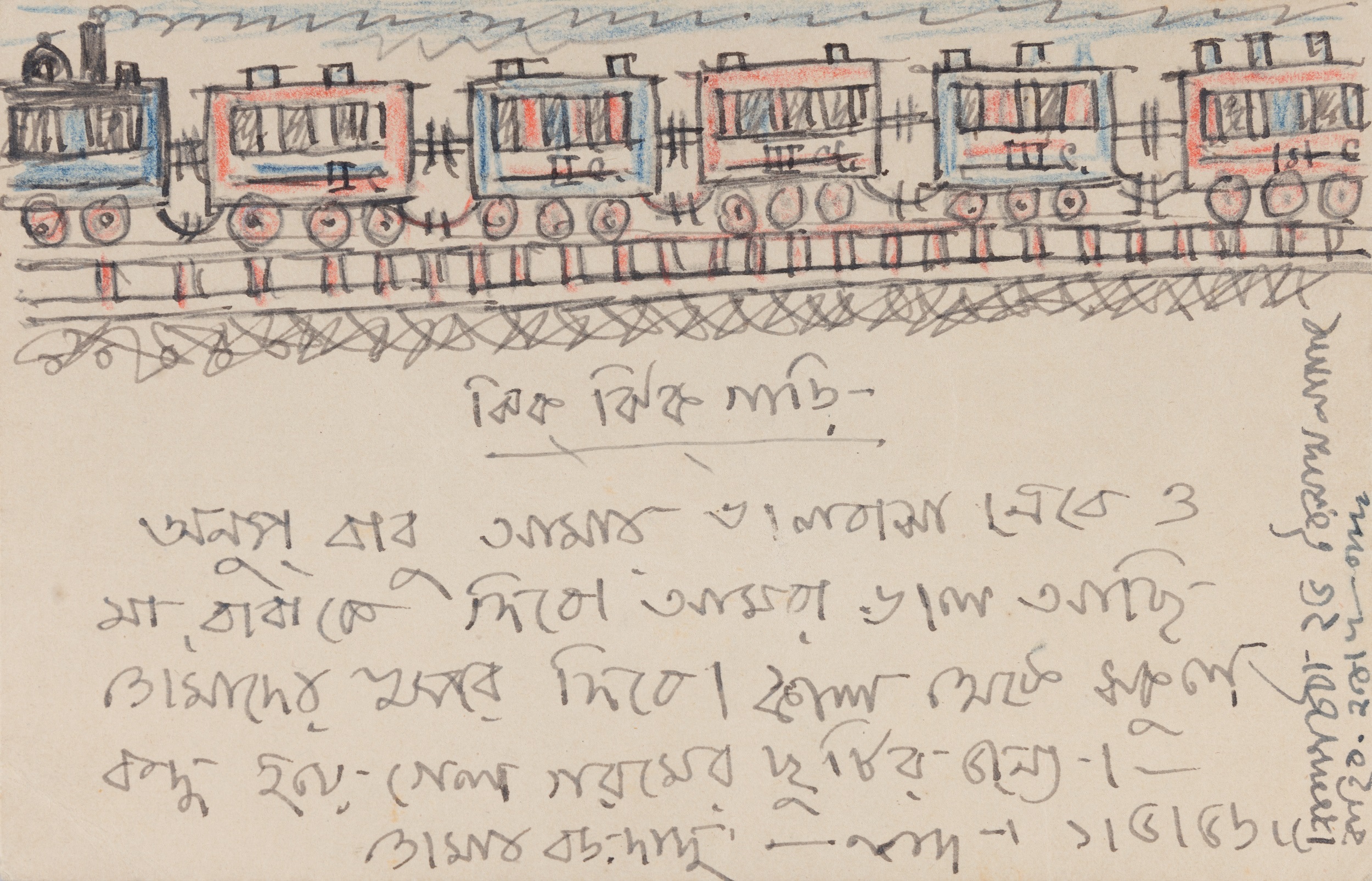

Nandalal Bose, Jhik jhik gaadi, Ink and pastel on postcard, 1956, 3.5 x 5.5 in. Collection: DAG

Beyond the celebrated 'aura' of their artworks and the often-stereotyped public image of the artist, there exists a more intimate and nuanced dimension of their lives that frequently goes unnoticed. A deeper engagement with artists’ archival materials—personal letters, sketches, and everyday ephemera—reveals a sustained and unrestrained expression of creativity to retain one’s childlike sense of enchantment with the world, often conveyed in playful modes. Such glimpses into their private world disclose how the artistic impulse could extend beyond formal modes of working towards ‘finished’ projects, manifesting instead as acts of tenderness, affection, and empathy woven seamlessly into their daily lives. Letter writing has been described by Virginia Woolf as 'the humane art’. Adding illustrations makes the letters feel alive and intimate, blending epistolary text with visual art to create a magical, immediate experience for the reader.

|

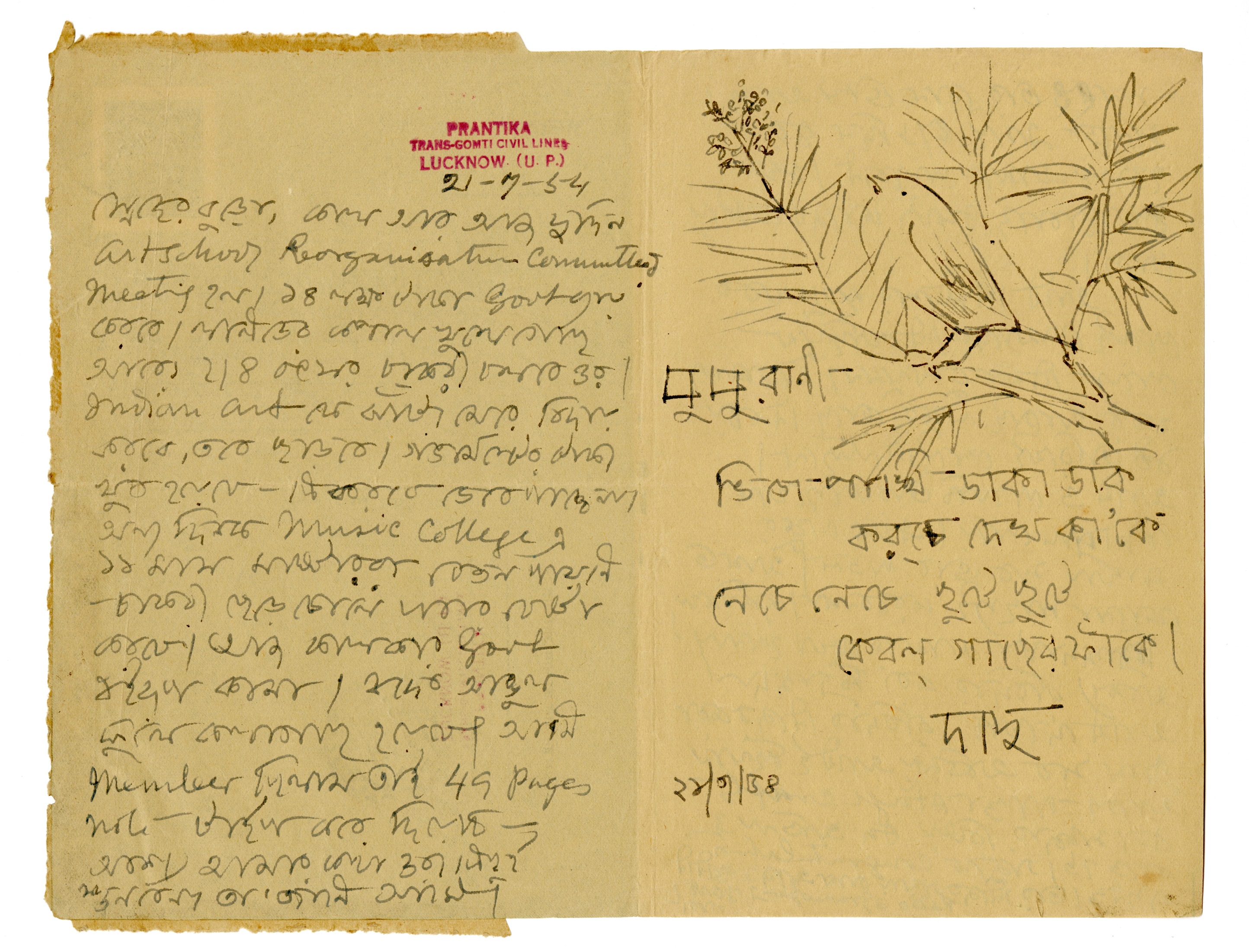

Asit Kumar Halder, Handwritten inland letter, 1954, 7.5 x 10.2 in. Collection: DAG Archive |

If we examine the personal correspondence of eminent artists such as Asit Kumar Halder, Chittoprasad Bhattacharya, and Nandalal Bose, we observe that portions of their letters addressed to grandchildren and nieces are frequently embellished with small drawings, often accompanied by rhymes and lighthearted commentary. These artistic inclusions underscore the artists’ enduring commitment to transforming the ordinary into the extraordinary—a testament to their understanding of a child’s fascination with fairy tales and imaginative narratives.

Asit Kumar Halder frequently corresponded with his granddaughter, whom he affectionately referred to as ‘Pupurani’. These letters often revealed the artist’s playful and humorous disposition, as he assumed the persona of ‘Dadu’ (grandfather) and created whimsical characters specifically for her enjoyment. On occasion, Halder would depict ‘Pupurani’ herself, imagining her as she embarked on new experiences, such as learning the alphabet. At other times, he would illustrate amusing figures with round heads and eyes, designed to entertain the young recipient. In letters sent prior to Durga Puja, he included drawings of the goddess’s idol, thereby sharing cultural and familial traditions. Collectively, these letters convey both a profound affection and a sense of longing for his granddaughter, as Halder resided in Lucknow, separated from her by several hundred miles.

Asit Kumar Halder, Handwritten inland letter, 1955, 7.5 x 10.2 in. Collection: DAG Archive

Nandalal Bose’s extensive practice of drawing and painting on postcards is well documented. These postcards offer glimpses into the artist’s immediate environment, capturing impressions of everyday objects, scenes, and situations within the limited confines of a small card. Nandalal’s daughter, Gauri Bhanja, resided in Mumbai for most of her married life, and her children—Nandalal’s grandchildren—often received beautifully illustrated postcards from their grandfather with little prompting. The subjects of these postcards ranged from a surreal depiction of a messenger pigeon flying across what is presumably the Arabian Sea, carrying an envelope inscribed with ‘Anup’ to deliver a message from their ‘Dadu’, to a striking close-up illustration of a charming chameleon, and the recurring motif of ducklings accompanied by their mother. These artworks undoubtedly brought immense delight to the children, who eagerly anticipated each new postcard from their grandfather.

Nandalal Bose, Untitled, Ink on postcard, circa 1957, 3.5 x 5.5 in. / 8.9 x 14.0 cm. Collection: DAG

Nandalal Bose, Untitled, Ink on postcard, 1955, 3.5 x 5.5 in. Collection: DAG

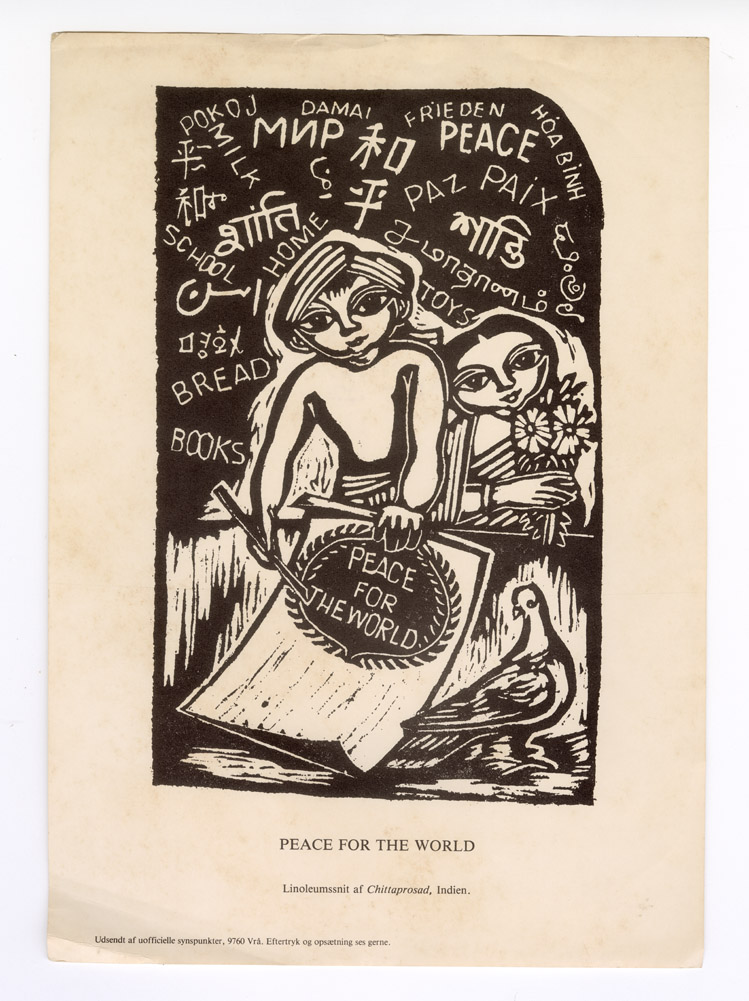

Chittoprasad Bhattacharya maintained extensive correspondence with his comrades, friends, patrons, and family members. These letters, written from his solitary residence in a single-room apartment on Ruby Terrace in Andheri, constituted a significant aspect of his daily life and provided considerable sustenance during his later years. Through his communications with long-standing friends and associates, one gains insight into his deep engagement with Indian history, his concern for the common people and their hardships, his observations on the prevailing political climate, and his pronounced dissatisfaction with these conditions. The letters also allow us to trace Chittoprasad’s evolving ideological stance, as he gradually distanced himself from the overarching doctrines of the Communist Party and embraced a broader vision of peace and harmony—a perspective increasingly reflected in his later works, particularly those centered on themes such as peace, children, and puppet theatre.

|

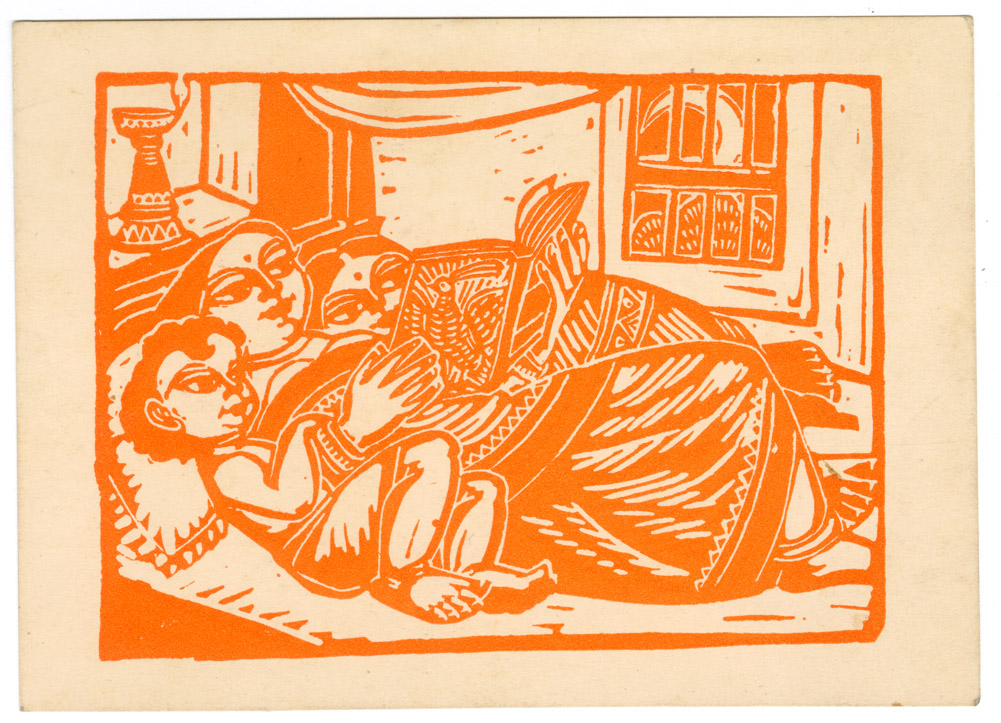

Chittaprosad, Monocolor postcard printed in Denmark, c. 1970, 4.0 x 5.4 in. Collection: DAG Archive |

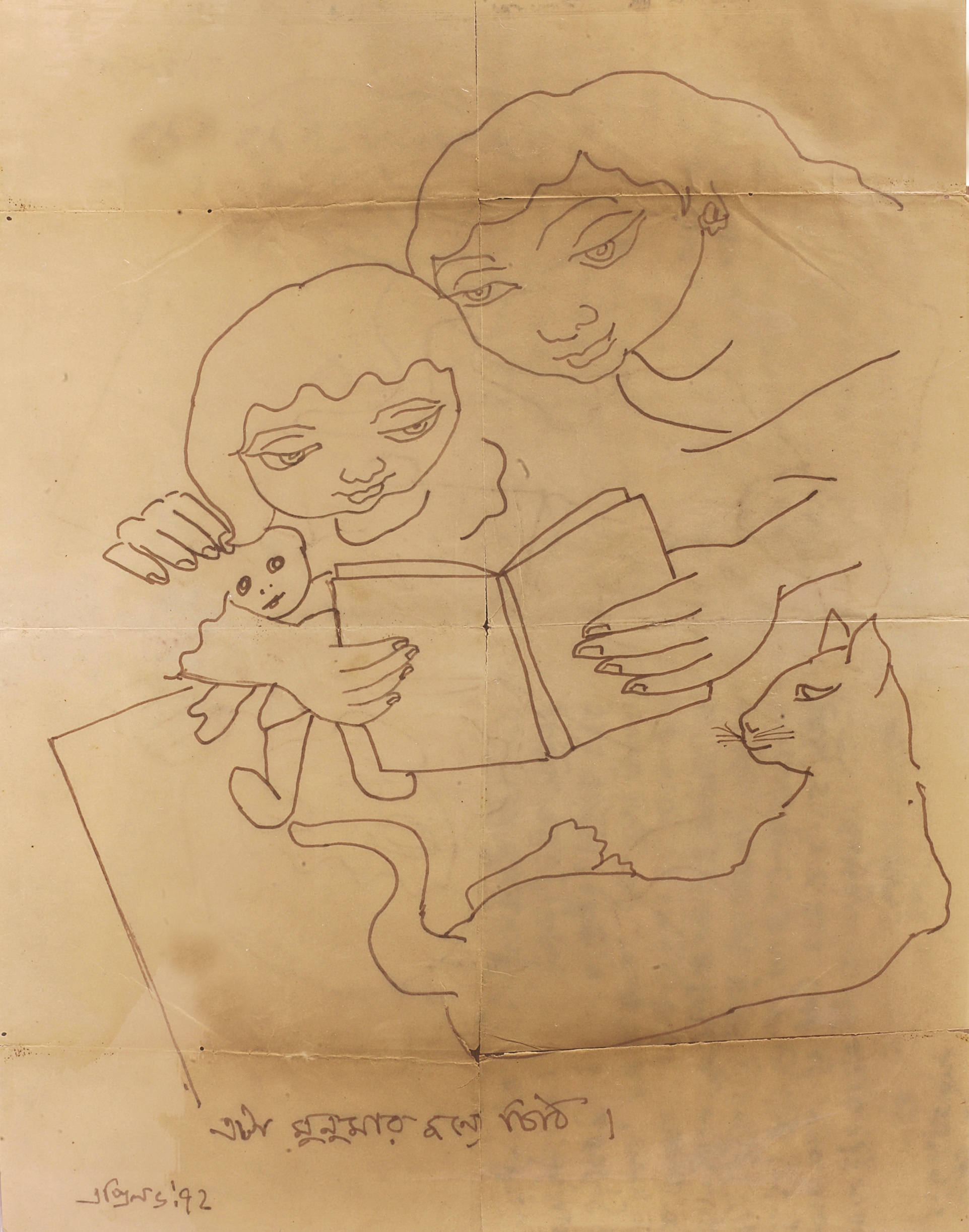

Furthermore, these correspondences reveal his enduring attachment to his younger sister, Gauri, which persisted until the end of his life. Gauri’s daughter, Gargi—Chittoprasad’s niece—held a special place in his affections. In his lengthy letters to Gauri, which often included detailed accounts of his own life and those of others, he regularly dedicated a separate section to address Gargi, whom he affectionately called “Munumaa.” This section typically contained expressions of love and affection, written in simple Bengali to accommodate the child’s developing language skills, along with a few drawings intended to offer Gargi an immediate glimpse into her uncle’s creative world. In a letter dated April 1971, for instance, Chittoprasad included a charming illustration of a mother and child with their pet, likely capturing a moment from their early reading lessons.

|

Chittaprosad, Munumaar jonyo chithi [Letter for Munumaa], Ink on paper, 1972, 10.2 x 9 in. Collection: DAG Archive |

These illustrated letters time and again remind us of the constant, immutable source of art that lie in joy and conviviality, in love and affection. The mainspring of creation cannot be the destructive forces exercised by the powerful and the influential at the expense of the casualties to the poor and innocent; it can neither be produced by the ‘non-human’ Artifical Intelligence. It is rather an effort at communicating, a creative effort to find means of reaching the other. And therein lies the power of art to delight, entertain and instruct, which can finally count against the instrumentalisation of social relations.

|

Chittaprosad, The Appeal [Peace for the World], Offset print on paper, c. 1970, Collection: DAG Archive |