Creating an Art-Integrated Classroom: T. F. I. Art Track Classes

Creating an Art-Integrated Classroom: T. F. I. Art Track Classes

Creating an Art-Integrated Classroom: T. F. I. Art Track Classes

All of us remember the colourful chaos of art class — splashes of paint, bright ideas, and the thrill of creating something visual. But the moment the bell rang for a double-period Math class, those vibrant images faded into a blur of black-and-white numbers and words.

This experience is shared by countless students across India and around the world, where engagement and understanding often increase when lessons in every subject are approached visually—for instance, through the use of videos and other visual learning tools.

That’s how Ritwika Chattopadhyay, a Teach For India (T.F.I.) Art Track Fellow teaching Grade 6 at Ek Tara, described her experience as part of the second phase of DAG’s collaboration with T.F.I. She has been implementing the art-integrated framework co-developed earlier this year by DAG’s Education Team and T.F.I. fellows from the previous graduating batch. ‘An art-integrated classroom is a space where every child participates and feels that their opinions matter,’ she shared. ‘They can question, challenge, and build on their peers’ ideas, rather than simply listening.’

So, what does this classroom look like, and how have fellows been working around the curriculum to make learning visual?

WHAT DO YOU OBSERVE?

Mrittika Mallick was teaching a Christina Rosetti poem on colours to Grade 2 students in Daffodils English School, which went, ‘What is blue? the sky is blue/ Where the clouds float thro'/ What is white? a swan is white/ Sailing in the light.’ The British poet was talking about the vivid colours of the English rural landscape like fields of poppies and sailing swans which young learners growing up in the city would be quite unfamiliar with. So, she picked a landscape which every child grows up seeing in some visual format—that of two figures bending to collect the harvest – miniscule against endless fields of Bengal.

|

Gopal Ghose, Untitled, 1958, Pastel on paper, 26.0 x 37.0 in. Collection: DAG |

The artwork was by the Bengal artist Gopal Ghose whose work is marked by a vibrant usage of colours which is immediately eye-catching to everyone—including young students. Thus, initially Mrittika asked them to undertake close viewing—which is the first step of the co-developed DAG and T.F.I. framework—and list down the colours they noticed in the artwork. To generate that personal connection, which was subjective in Rosetti’s poem, she then asked them to relate them to natural materials which they saw in the work—if someone said green, the material they’d say would be grass. Then she redirected their attention and read out the poem, explaining how someone else saw yet another rural landscape through colours. Understanding through personal interpretation becomes significant to prevent rote-learning and a more embodied manner of learning, she noted after the class.

MAPPING IT OUT

Somopriya Debgupta was conducting an English class at Madurdaha Satyavritti Vidyalaya, where she was teaching Robert Frost’s ‘The Road Not Taken’ to Grade 6 students. But beyond poetry analysis, she had a deeper goal in mind. With most of her students being girls, Somopriya wanted to spark a conversation about how societal expectations often link gender to career choices—encouraging them to imagine and explore the many alternate paths life can offer.

To make this personal connection visible, Somopriya mapped her own thoughts and her students’ ideas on the board—a process central to our framework, as it allows learners to see the entire journey of their thinking unfold before them. She began by introducing the objective of the lesson: What happens when young people choose paths they are often discouraged or forbidden from taking?

To explore this, she selected an oil painting by Bengal artist Sudhir Ranjan Khastgir depicting a Manipuri dancer, and invited her students to observe it closely. She asked them to consider whether it might have been difficult for the girl in the artwork to pursue dance as a profession in the early twentieth century. These prompts—open-ended questions that encourage students to unpack elements of an artwork—evoke creative and emotional responses, nurturing curiosity and fostering democratic, participatory learning spaces where students take ownership of their learning.

|

Sudhir Ranjan Khastgir, Untitled, Oil on Masonite board, 121.9 x 61.0 in. Collection: DAG |

Listing down every prompt she asked the students on the board, she attempted to finally look beyond the elements of the artwork, into their real life—which is ultimately the aim of any art-integrated classroom—to inculcate critical thinking and enable students to make connections from their curriculum to their everyday life. She brought them back to modern day personalities they’d be familiar with like Mary Kom for boxing or Uday Shankar for dance and asked them to ponder on the gender norms and ideas of who belongs where. ‘Thoughtful boardwork for me transforms the classroom into a visual story,’ she said, ‘It helps students to see the idea before they begin to understand and then question it.’

MAKING CONNECTIONS

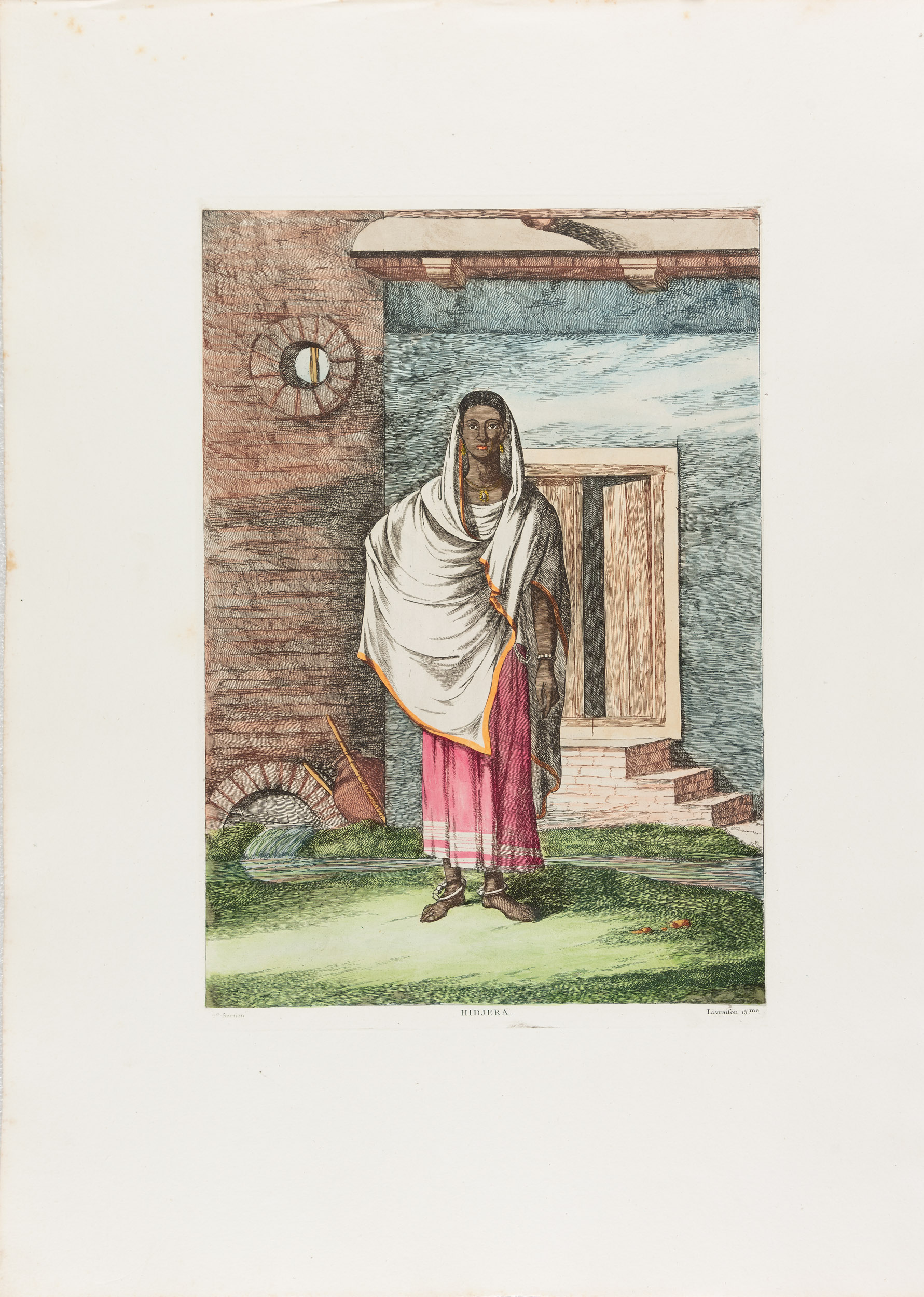

How does one start talking about caste in middle school classrooms? Ritwika wanted to bank on students’ prior knowledge and build on that to ask them the larger question of caste inequality and discrimination in India—towards that, she wanted to use portraits printed by the Danish painter and printmaker F. Baltazard Solvyns of people he saw when he arrived in Bengal in the eighteenth century. Solvyns primarily categorised people according to their professions, which was very much linked to their castes—a method that has since been critiqued as a quite limited, and often harmful, way to visually segregate a population.

|

F. B. Solvyns, Hidjera [hijra, eunuch], Colour etching on paper, 14.17 x 19.29 in. Collection: DAG |

After an initial observation of two figures—a palanquin bearer standing before a house and a portrait of a man from the Shudra rung of the varna system—the students began to look closely for visual clues or caste markers that Solvyns had emphasised. These details helped them infer who these individuals might have been and what level of privilege they were afforded within society. As Ritwika introduced the caste system and explained how it has historically restricted people’s occupations, the students began drawing connections to their own lives and surroundings, questioning whether it is fair for social divisions to persist based on the Brahminical hierarchy.

Using the technique of mapping their learning on the blackboard through observations, comparisons, and inferences proved especially effective. The discussion soon expanded into a more personal space, with students sharing their own experiences and stories of discrimination. ‘The students inferred conclusions on the caste system, based on what they observed while comparing the artworks,’ she said, ‘The key understanding of the unfairness of the caste system was reached through a lively debate between them.’

|

Chittaprosad, Untitled, Linocut on paper, 19.1 x 25.9 in. Collection: DAG |

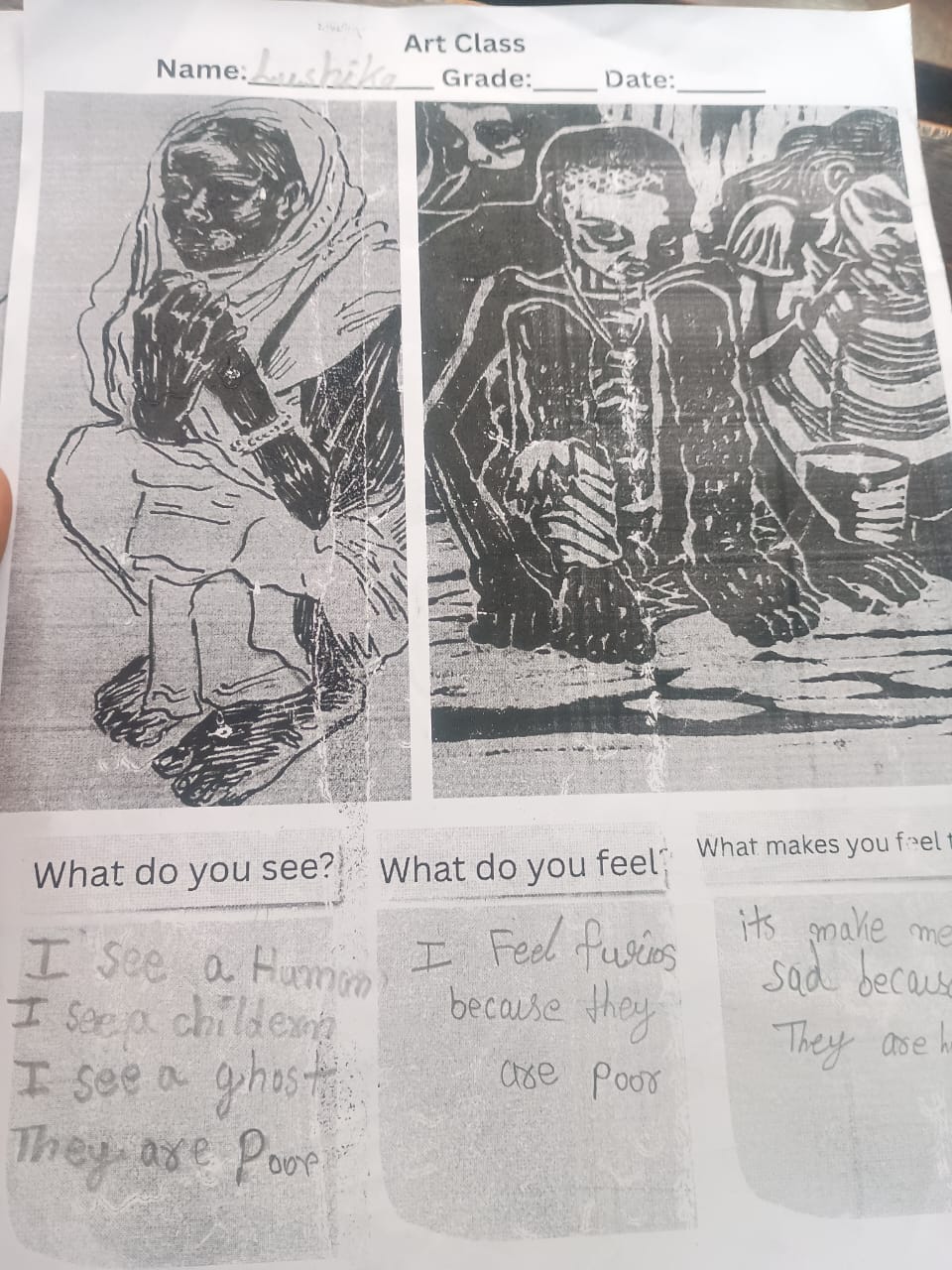

Expressing Feelings

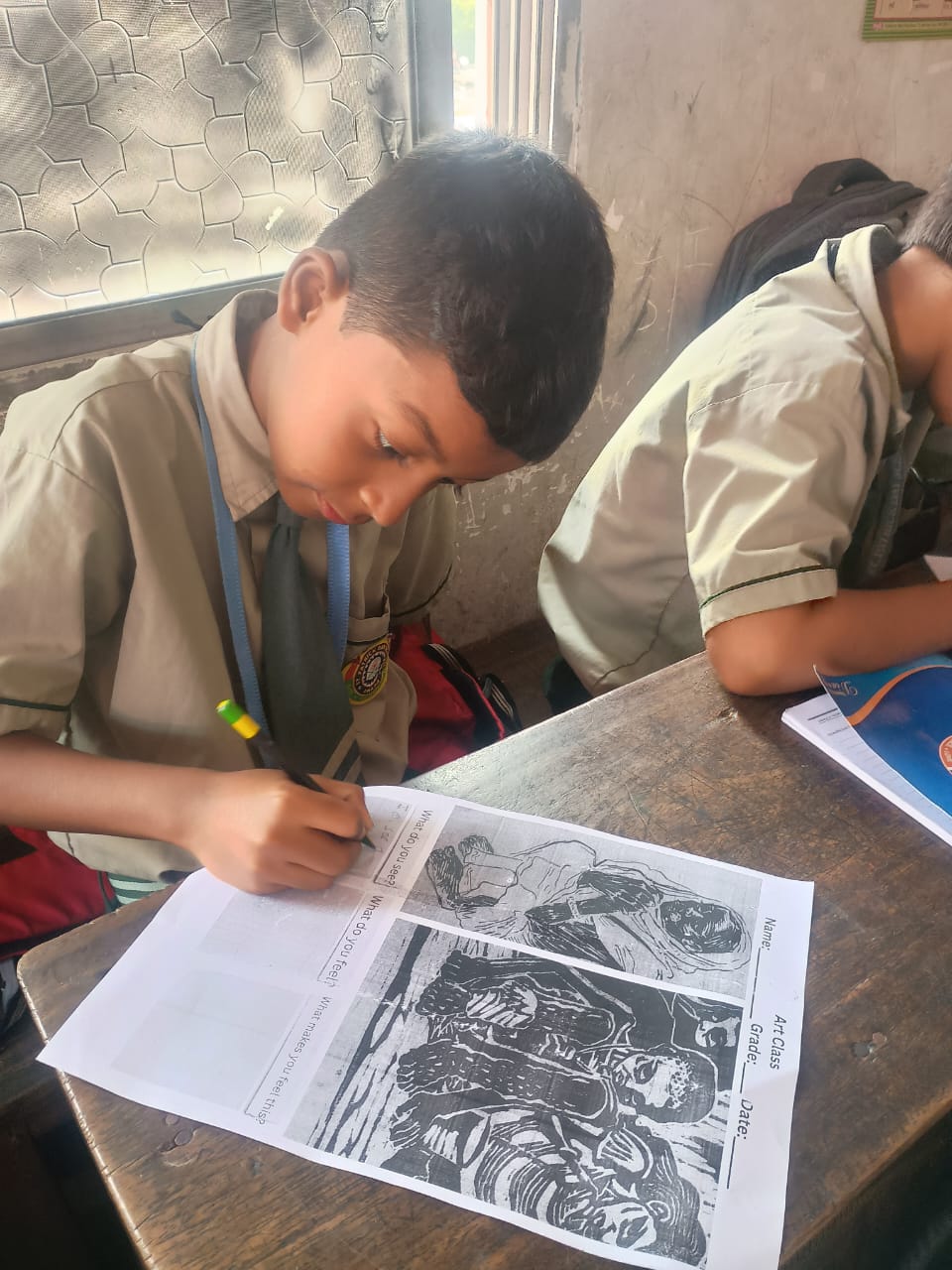

Subham Samaddar who teaches Grade 3 at St. Patrick’s Day school wanted to use the time of the Morning Meeting to understand how his students are comprehending the images of the genocide in Gaza that they are seeing around them, online and in newspapers. The morning meeting is specially designed by T.F.I. as the first thing in the morning that students do, where they pause and reflect on their feelings and what they’re looking forward to doing during the day. It’s a way of inculcating a sense of responsibility and ownership in students’ decision-making.

Subham chose not to use images from Gaza, but instead drew from another moment of human suffering—the Bengal Famine of 1943. During this period, artist Chittaprosad travelled across Bengal documenting the lives of the famine-stricken, and these works went unpublished at the time due to British censorship. One particularly striking image Subham used was an untitled linocut print by Chittaprosad depicting three starving children in Cox’s Bazaar (now in present-day Bangladesh), their frail bodies marked by extreme malnutrition. Displaying these images on the board and distributing them as worksheets for silent reflection, Subham asked his students three simple yet profound questions: after identifying what they were seeing, how did the images make them feel, and why did they think they felt that way?

All fellows working with their various grades and subjects are taking ahead the collaborative curriculum developed with DAG and T.F.I., and developing modules around it depending on the needs and contexts of their classrooms. This differentiated instruction has made the artwork accessible to a wide demography of learners for whom the DAG collection and their own curriculum have come alive through mediated facilitation where learning is based on making connections rather than rote. It’s an inquiry-based learning framework which is at the core of our education programmes where dialogue is what leads classrooms.