Chronicling the Durbar: Images and voices from DelhiThe Editorial Team October 01, 2023 The three Delhi Durbars, held by the British colonial administration in India in the years 1877, 1903 and 1911, were occasions to flaunt their colonial possessions in South Asia, while achieving certain specific goals with each event. Meant to act as a stage where the ceremony of imperial power was displayed to full advantage, the events attracted widespread commentary from writers and journalists who sought to document each of these events, which were then produced as lavish books with photographs, painted or engraved plates, drawings and maps, bound in gilded leather. Who were the significant chroniclers of the Durbars? Read below to find out. |

|

The Imperial Assemblage of 1877 J. Talboys Wheeler wrote an account of the 1877 Durbar, titled The History Of The Imperial Assemblage At Delhi, reflecting at the titular level an attempt by the British to both distance themselves from the Mughal ‘Durbar’ and, at the same time, draw from its performative significance. Wheeler was described as a ‘bureaucrat-historian’ and was a former newspaper editor and professor of Moral and Mental Philosophy at Madras Presidency College, who advocated closer contact between the British and Indians. |

|

|

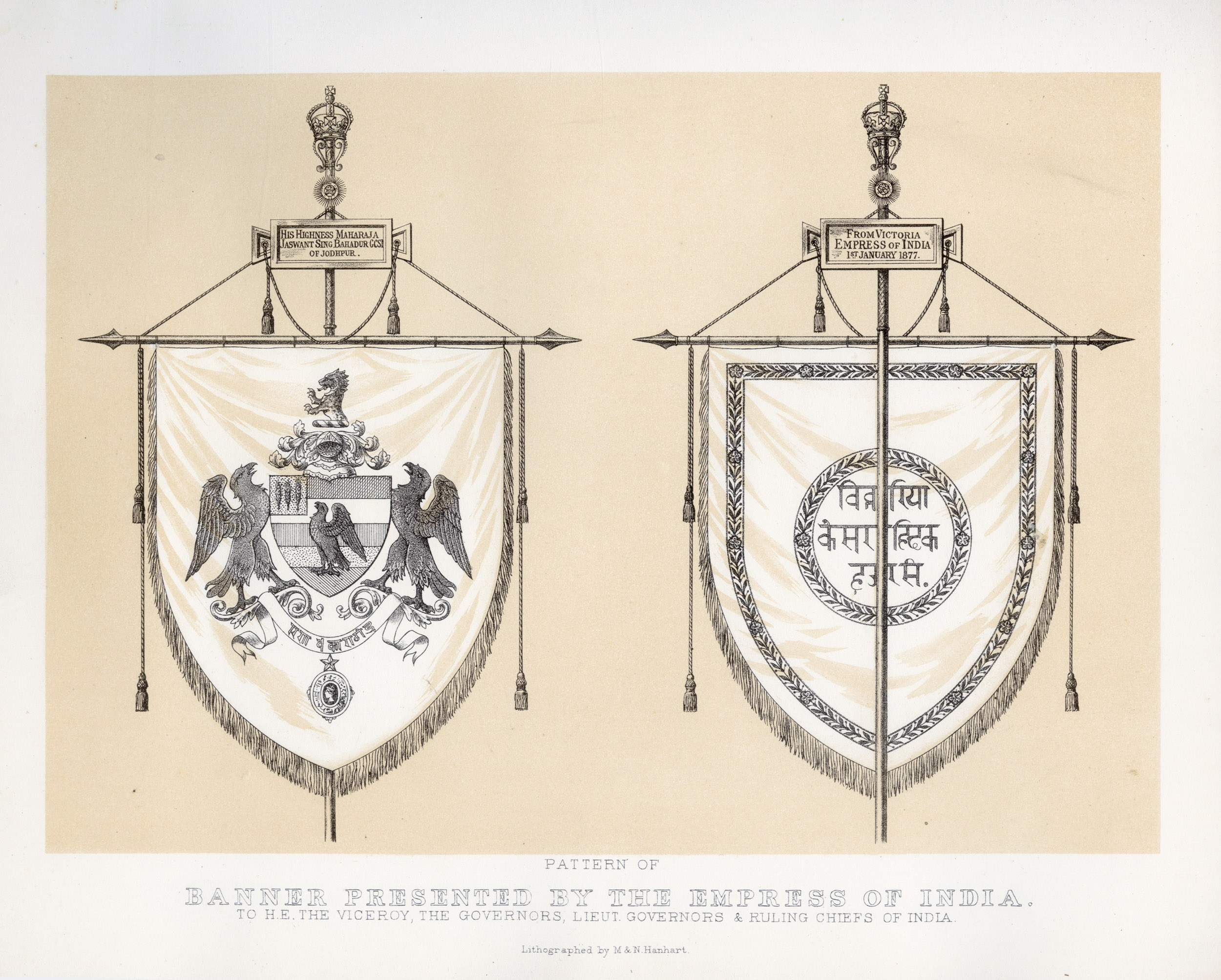

Banners, each bearing the coat of arms of the respective ruling house, were presented by the viceroy to the princes on the occasion of the assemblage. These coats of arms had been designed by a British civil servant

Collection: DAG

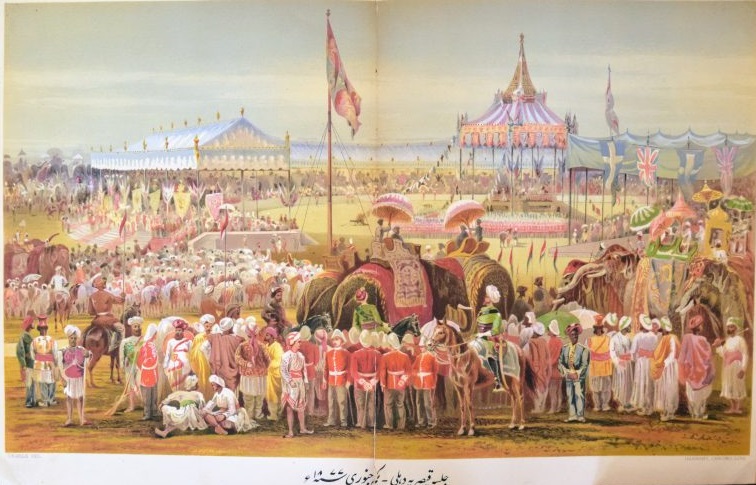

Illustration from Piyare Lal’s Tārīk̲h̲-i jalsah-yi Qaiṣarī (1883), an Urdu translation of James Talboys Wheeler’s The History of the Imperial Assemblage at Delhi (1877)

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Wheeler's chronicle of the first Imperial Assemblage in 1877

The primary significance of the Assemblage was for Queen Victoria to assume the title of ‘Empress’, even though she did not visit India herself. Another significance was to establish the intimacy between the colonial rulers and the various ‘native’ princes of India, thus drawing an unbroken chain between India’s older rulers and their new ones. Repurposing the new title of the ‘Imperial Assemblage’, Wheeler wrote: ‘An Imperial Assemblage is one of the oldest institutions in India. From the remotest antiquity the Rajas and princes of India have assembled to celebrate the establishment of a new empire, or the accession of a new suzerain. The story of such gatherings is told in the earliest traditions of the two famous Hindu epics, — the Ramayana and Maha-Bharata. To this day the memories are household words throughout India. In the age of Rajput sovereignty such meetings were known as Raja-suyas and Aswamedhas. In the age of Muhammadan rule they were known by the name of Durbars.’ |

V. B. Pathare

Indraprastha, Delhi

Watercolour on paper, 38.9 x 26.7 cm., c. 1950

Collection: DAG

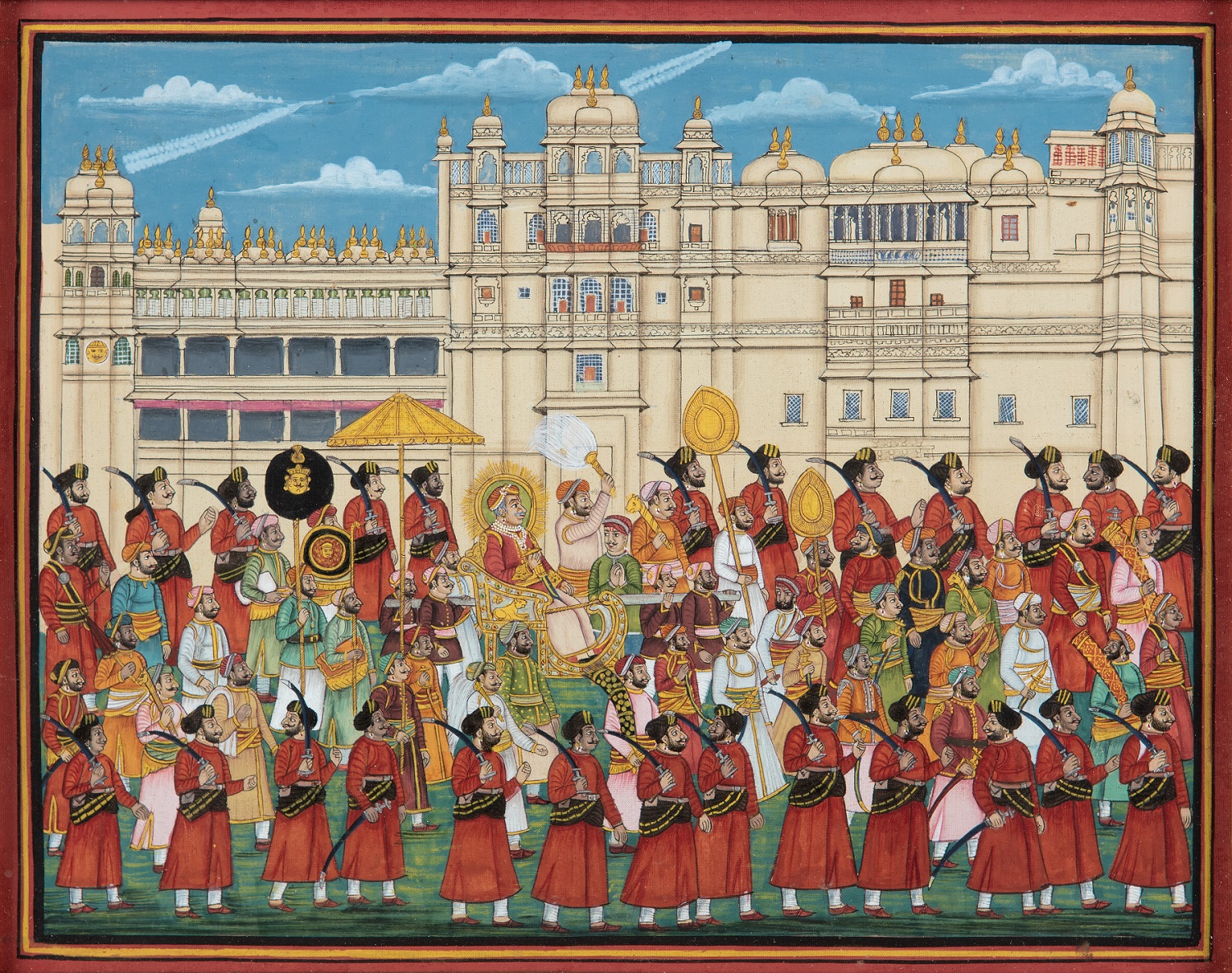

Unidentified artist

Maharana Bhupal Singh of Udaipur/ Mewar in procession in front of the City Palace

Gouache highlighted with gold pigment on fabric pasted on cardboard, 19.6 x 24.6 cm., Mid-late 20th century

Collection: DAG

To justify why Delhi was chosen for hosting the event, instead of Calcutta—the colonial capital of the time—Wheeler went back even further in time, into the realm of myth: ’There is no city in the British empire so fitted as Delhi for the assumption of the sovereignty of India. It is seated near one of the most ancient sites in all India. It is associated with nearly every era in the history of the past, — Rajput, Muhammadan and Mahratta… They stand in the midst of relics which belong to the remotest antiquity; the remains of a metropolis which may claim to be coeval with the oldest cities in the ancient world. The ruins of Indraprastha, the “precinct of Indra,” lie buried beneath the neighbouring mounds. The kings, the nobles, the once teeming population have shrivelled into dust and ashes. The traditions are preserved to this day in the Hindu epic of the Maha- Bharata.’ The Imperial Assemblage was not just an act of renewal, but also revival of many other claims of authority upon the capital throughout its temporal and imagined pasts. |

The proclamation dais, designed by Lockwood Kipling

Collection: DAG

The amphitheatre for the imperial assemblage of 1877

Collection: DAG

The administration was still anxious two decades after the revolt of 1857 nearly displaced British rule from Delhi, so it sought to be unambiguous in the visual messages it offered. Commenting on the architecture, especially the temporary structures built to host the spectators during the Assemblage, Wheeler wrote: ‘There was nothing oriental in these structures. They were not borrowed from any native designs. They were tented pavilions covered in to keep off the sun, otherwise they were exposed to the open air. They were rich in colour, as was suitable beneath an Indian sun.’ For instance, the dais, from which the viceroy proclaimed the assumption of the imperial title by Queen Victoria, was designed by Lockwood Kipling, and came in for some criticism for its ‘Victorian feudal’ style. Wheeler’s book also carried photographs of famous Delhi monuments like Humayun’s Tomb, the Qutub Minar and the Kashmere Gate, taken by the Bourne & Shepherd studio. |

|

King Edward's Durbar of 1903 The 1903 Durbar attempted to reproduce many of the elements of the previous assemblage, while adding a few features of its own. According to a historian, ‘The basic contours of the event, which was held in the winter of 1902-03, were similar to the one of 1876-77—a showy ‘state entry’ procession, the main proclamation held in an amphitheatre built on exactly the same spot as the previous one, a focus on the princely rulers of India, the creation of large tented camps in the neighbourhood of the city.’ |

|

|

Unidentified artist

The Imperial Durbar' (The Durbar of 1903)

Chromolithograph on paper, 49.5 x 66.5 cm.

Collection: DAG

|

Organised by Lord Curzon, the ceremony was also meant to signal the obedience of Britain’s colonial subjects in the face of a rising tide of Swadeshi sentiments, and the obsolescence of India’s princely rulers, who no longer posed any realistic political threat to the British and could be safely enjoyed as pure spectacle. The official historian of the event, Stephen Wheeler, described the appearance of the Indian rulers thus: ‘not so much a series of Indian Chiefs, mounted in their pride, to be scanned, as each went by, like portraits in a picture gallery; but rather a resplendent vision of Asiatic pomp, interminably changing, in colour and arrangement, like tints in a kaleidoscope, yet, in its general aspect, ever the same…’ |

Mortimer Menpes' book on the Durbar

Collection: DAG

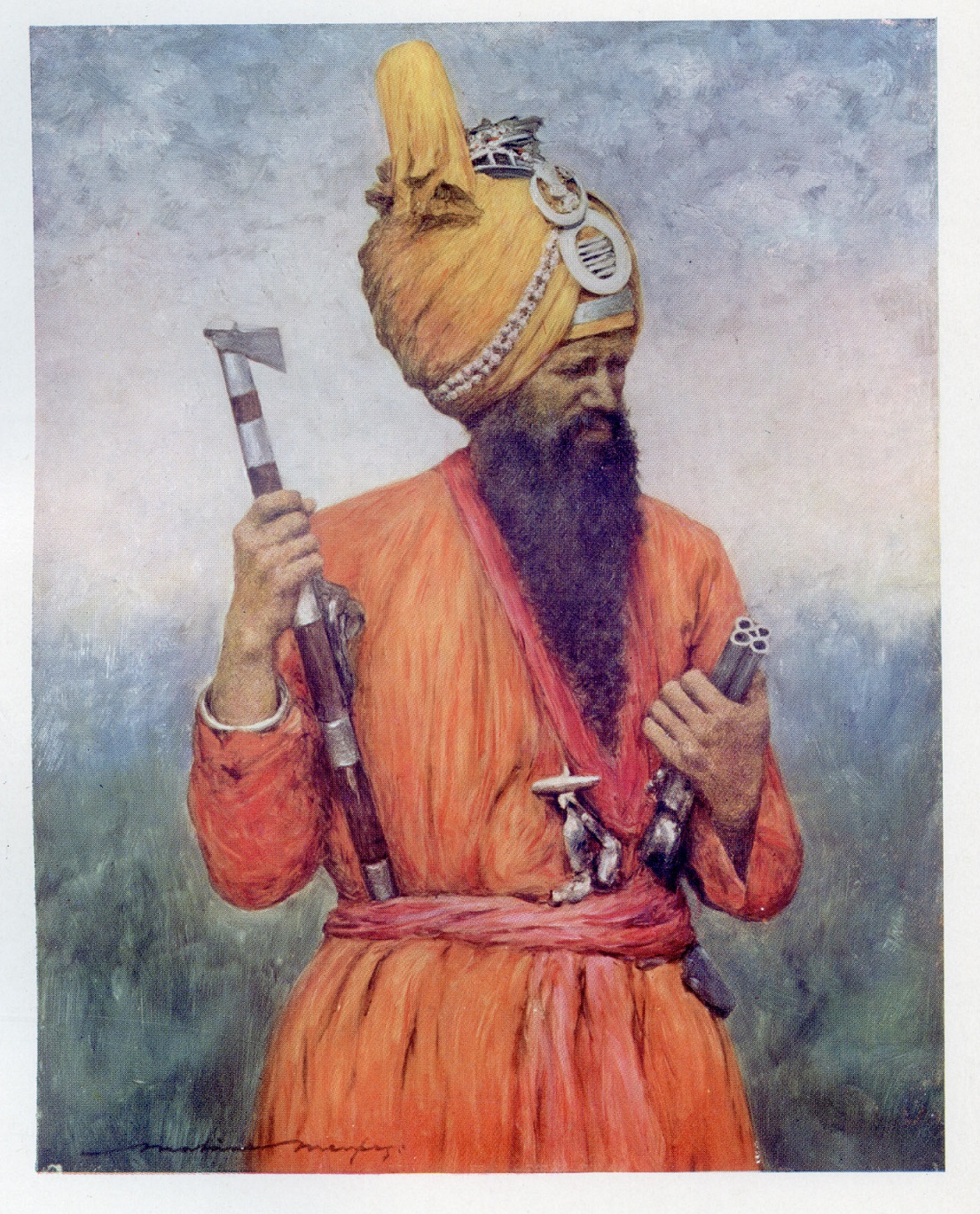

Mortimer Menpes

A Standard-Bearer of Jaipur

Oil on plywood, 41.1 x 33.0 cm., 1903

Collection: DAG

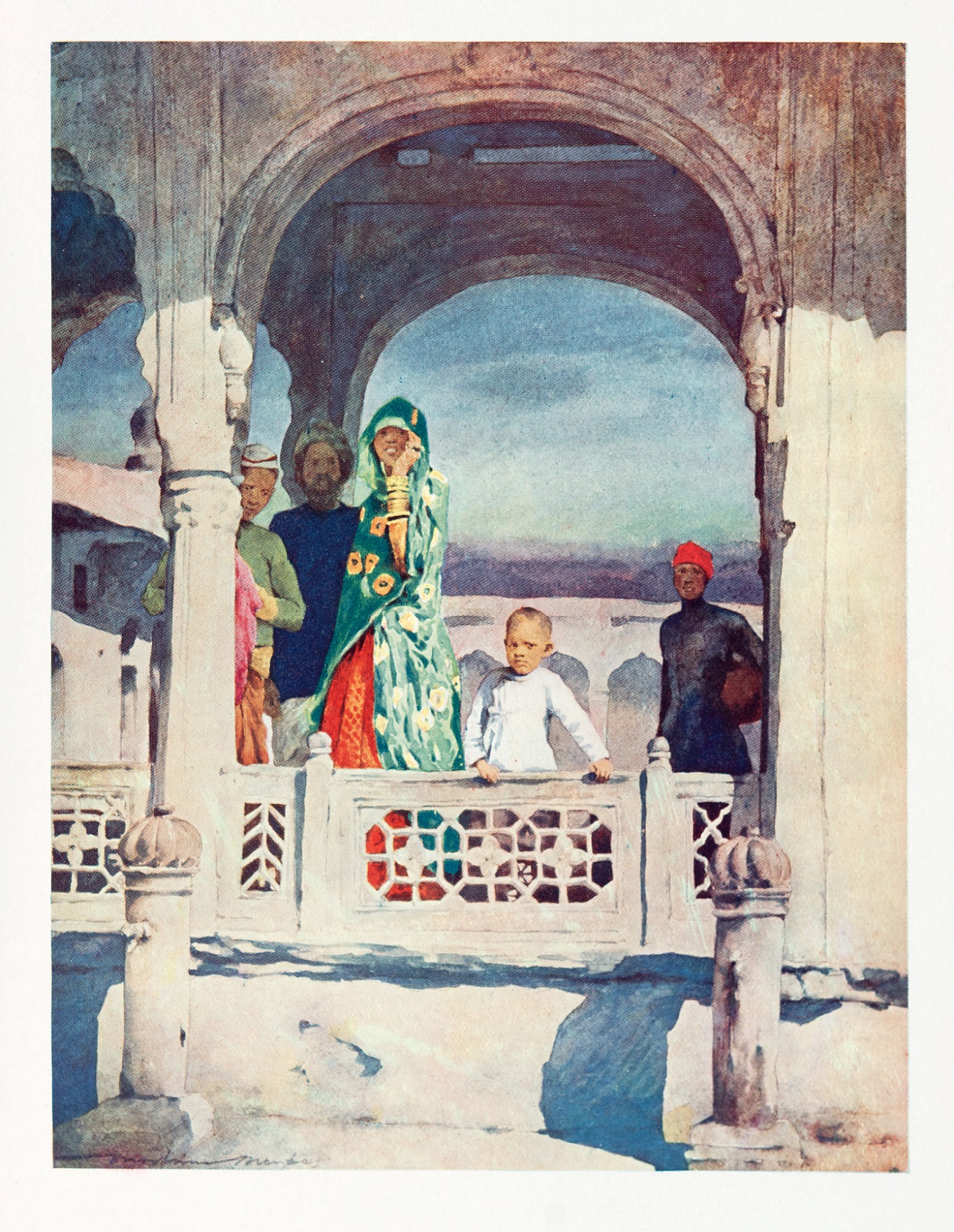

Accompanied by many kinds of images, including engraved plates, stereographic photographs and postcards, the publications around this Durbar did their best to reproduce the splendour of the event. While it attracted many chroniclers, one of the most important text and picture albums was made by Mortimer Menpes—an Australian-born British painter, author, printmaker, and illustrator—and his daughter, Dorothy Menpes. He created a series of watercolor paintings and etchings depicting the Durbar and stayed in Camp Number One called ‘The Millionaires' Camp’ in Delhi. Dorothy wrote the text for The Durbar. |

Menpes used the occassion to highlight the various costumes and finery worn by the princes and their retainers

Collection: DAG

The Jama Masjid was used as a vantage point by spectators to see the procession enter the city

Collection: DAG

Menpes brought out the romance of the occasion, not least by his references to the work of J. M. W. Turner. Commenting on the most anticipated event, the ‘state entry’, he wrote: ‘This was a scene for Turner. Turner, who could paint the sun, was the only man to paint this procession of native rulers … a group of elephants in gold, emerald green, and jewels, looking like bubbles ready to burst with brilliance, and making the surrounding colours faded and pale by comparison. For once one felt grateful to the dust, the dust that at times rose in clouds and hid portions of those marvellous colour-schemes from our sight, as with a curtain of yellow gauze, bestowing upon them a dream-like mystery marvellously enhancing their unearthly beauty.’ When he found a particular display lacklustre, on the other hand, he felt the need to point it out, contrasting oriental splendour with western ‘ugliness’: ‘…the colour was a little saddening; and the costume was evidently disappearing, scumbled over by Western ugliness. The men knit themselves together and marched squarely in rigid lines. They were more angular and had less of that delightful swing and looseness so characteristic of the East.’ |

|

The Durbar of 1911 To mark the accession of George V to the British throne another Durbar was organized in 1911. This edition of the Durbar, however, would mark some changes from the previous one, reflecting the colonial administration’s apprehensions regarding the strengthening of the national movement in India. As a historian writes, ‘The viceroy, Charles Hardinge, agreed with the secretary of state in Britain, Lord Crewe, that the durbar had to be for India and the Indian people. Moreover, though the princes would be present and pay homage as before, the representatives of British India were to be given a prominent part in the proceedings too.’ For the Durbar of 1911, the throne pavilion was designed with a gilded dome and zardozi embroidered canopies. It was placed so as to enable the large number of spectators in the stands a view of the royal couple. |

|

|