Bourne's Legacy: Tracing Samuel Bourne's travels in IndiaAnkan Kazi October 01, 2023 Samuel Bourne (1834—1912) was a British photographer known for his prolific seven years' work in India, from 1863 to 1870. Landing first at Madras, then Calcutta, he travelled across the subcontinent and wrote about his first impressions of the places he visited. Bourne's photographs were produced primarily for the European market and provided a glimpse of India as a distant, exotic land that was being rendered more ‘familiar’ by its colonial rulers. In 1864-65 he joined William Howard in Shimla and set up ‘Howard & Bourne’, which merged with the photographic establishment of C. Shepherd and A. Robertson. Howard dropped out, and eventually, so did Robertson, leaving Bourne as the senior ‘active, creative partner’ in the newly named chain of studios ‘Bourne & Shepherd’. How did he contribute towards the project of visualizing India, especially as the task of photography began to shift from documentation to artistic representation? |

Samuel Bourne

Tomb of Nizam-ood-deen. Delhi (Nizamuddin’s Tomb)

Silver albumen print on paper mounted on card, 8.0 x 11.2 in. / 20.3 x 28.4 cm. c. 1860s

Collection: DAG

|

Along with photographing the people, built-structures, gardens and wildernesses of India, Bourne led some of the earliest photographic expeditions across the Himalayas, capturing their complex terrain, glacial forms and its serene, awe-inspiring beauty. His negotiations with the landscape and the thrill of the obstacles he faced were amply reflected in the letters he wrote to the British Journal of Photography. In this article, we will take a look at some of the most famous photographs he took across India. |

|

Samuel Bourne Mausoleum of the Emperor Humayoon, Delhi Silver albumen print on paper mounted on card, 8.5 x 11.7 in. / 21.5 x 29.7 cm., c. 1860-1870 Collection: DAG |

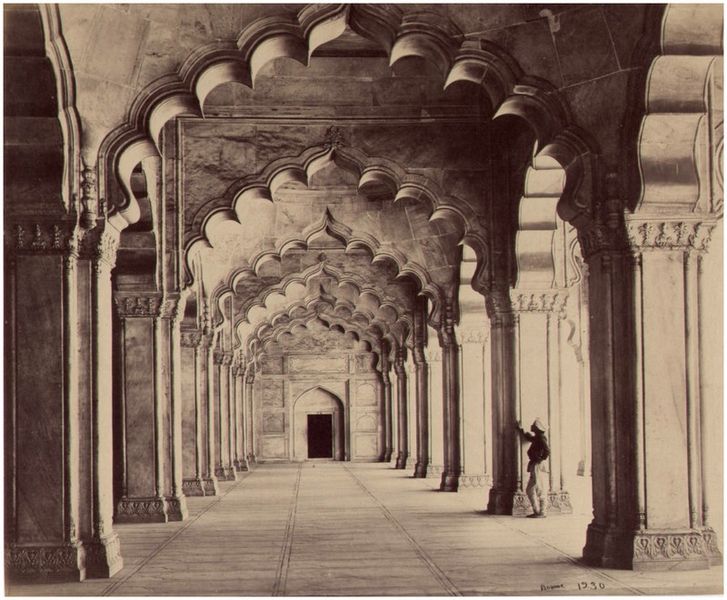

Moti Masjid

c. 1866

Silver albumen print on paper, 22.8 x 27.9 cm.

Collection: DAG

Interior view of the Moti Masjid [Pearl Mosque], Agra, India

c. 1866

Silver albumen print on paper, 11.0 x 9.2 in. / 27.9 x 23.4 cm.

Collection: DAG

General View of the arches, Delhi (Quwwat-ul-Islam mosque)

c. 1866

Silver albumen print on paper, 11.0 x 9.2 in. / 27.9 x 23.4 cm.

Collection: DAG

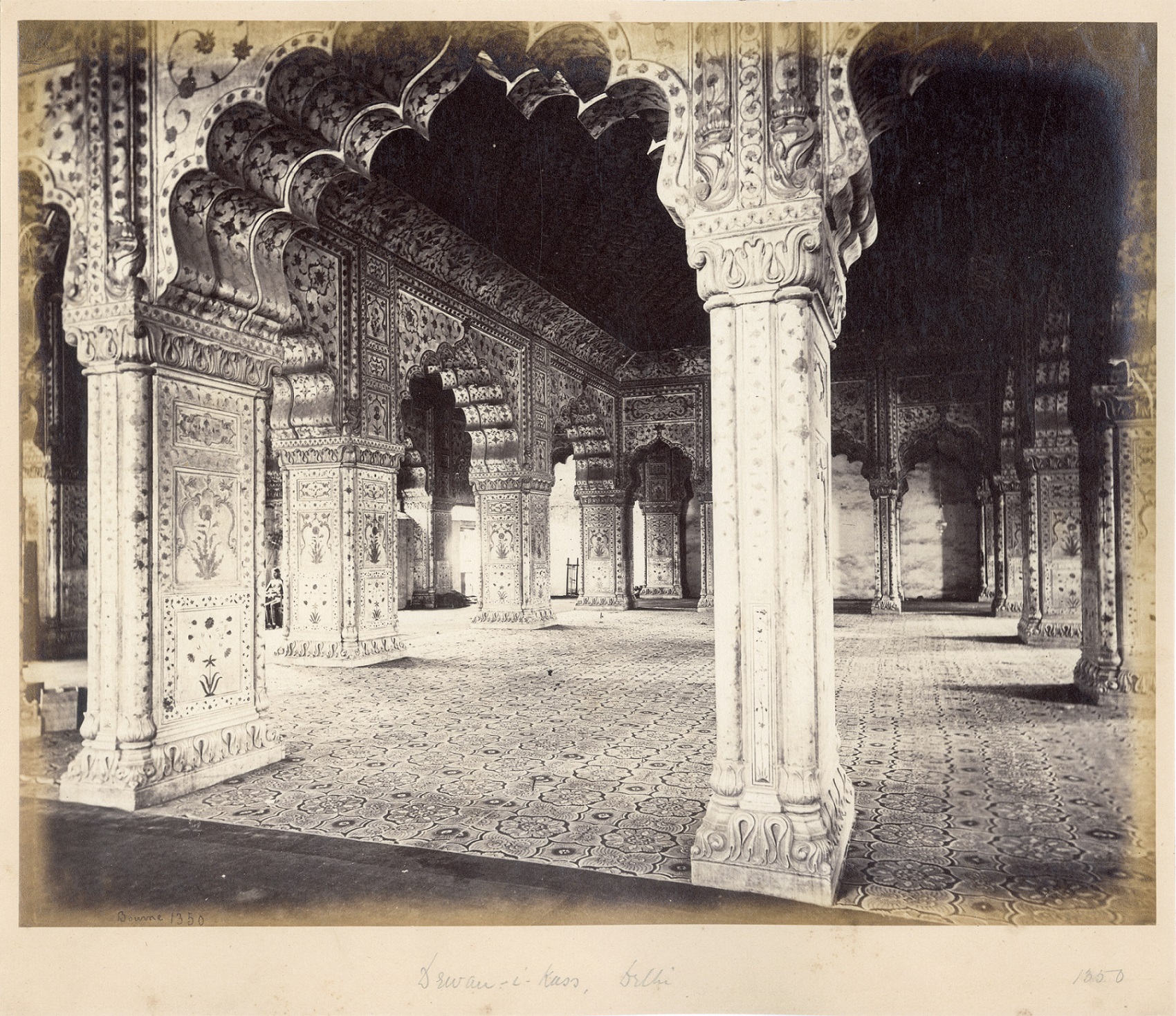

Photography as artSamuel Bourne wrote about the status of the photographic image in India, where he thought it was held in greater artistic regard, compared to its bare scientific status in Europe at the time. This may have encouraged him to make his own photographs aspire to a higher condition of fine art, rather than merely documentation. In images he made of structures like the Moti Masjid (the Pearl Mosque, situated within Delhi’s Red Fort), patterns and echoing forms are emphasized —allowing viewers to imagine themselves in the complex itself, rather than observing it from outside. After visiting an art exhibition held in Lahore in 1864, he wrote: ‘Unlike the treatment which photography received last year at the hands of the Commissioners in London it is here classified as one of the fine arts. Are we then more enlightened, or simply more just and unprejudiced in this land of rising British enterprise than the would-be patrons of art in professedly free but somewhat clique-ridden England?’ |

|

He also tried to convey these structures’ powers to enchant the viewer, often writing about a particularly ‘remarkable’ pillar, or waiting for auratic streams of light to flood these halls or spaces before capturing their images. |

|

|

The Government House, Calcutta

c. 1866

Silver albumen print on paper

Collection: DAG

Bengali villagers outside thatch houses, and a bullock cart near roadside

1863

Collection: DAG

The Cashmere Gate, Delhi

Silver albumen print on paper, 1860s

Collection: DAG

Taming the ColonyCompared to the majestic older buildings and structures from the subcontinent, such as the Fatehpur Sikri or the Taj Mahal, Bourne found the new colonial architectural style employed by the British, especially in Calcutta, to be severely wanting, describing the latter city to be ‘a place totally devoid of architectural beauty’. He preferred, instead, some of the more primal scenes that allowed him to contrast the wilderness of untamed nature to the ordered landscapes and gardens being built by the British. On the other hand, he registered the lasting influence of Delhi’s buildings, even though the city had achieved notoriety for the events of 1857, writing, ‘Delhi can’t fail to be of interest to the photographer: the ‘Cashmere Gate’, the fort, and other noted places must be taken, while its mosques and similar buildings will be photographed for their own merits.’ Even though he was genuinely interested in photographing the structures and sites of Delhi, as commentators have noted, Bourne was also conscious of the British public’s demand for images from the site of the infamous revolt of 1857. |

|

It also accounts for some of the well-known images he took in Kanpur, especially of a cenotaph, surrounded by an ordered garden, that was built to commemorate British victims of the 1857 mutiny who were thought to have been pitched into a well. |

|

|

From Thibet Road, Pangi

Collection: DAG

Photograph of a view near Teranda, Himalaya from the 'Strachey Collection of Indian Views'

1863

Collection: DAG

Kashmir Scene

albumen print from collodion negative

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Containing the PicturesqueWhile the aesthetic of the picturesque, to which Bourne was committed, required sublime landscapes to fit perfectly within the frame of the camera’s field of view, this was often a difficult task on Indian ground. Rivers, glaciers, peaks of mountains and valleys frequently dispelled any attempt to capture them through a singular position or view. ‘Yet’, as Sampson writes, ‘this only challenged him to produce more than one view of a given area, often with the most subtle variations and in two or three different formats, by which he was able to expand the possibilities for comprehending the unwieldy and very often un-picturesque topography encountered on his treks.’ |

|

In Kashmir, he was frequently struck by the grandeur of the views he saw before him, which drew out a distinct spiritual or mystical side to his endeavours (he was a devout Unitarian, according to his friends): ‘What a scene was the whole to look upon! And what a puny thing I felt standing on that crest of snow!—a mere atom, and scarcely that in so stupendous a world! To gaze upon a scene like this till a feeling of awe and insignificance steals over you, and then reflect that in the midst of this vast assemblage of sublime creation you are not uncared-for nor forgotten, cannot fail to deepen the veneration of every right-feeling man for that Almighty, but Beneficent Power, who upreared the mountains, and in whose hand is the breath of every living thing.’ At the end of his first expedition to the Himalayas, he wrote: ‘I had been absent ten weeks, and with the exception of a broken ground-glass, returned with all my instruments uninjured, and with a stock of 147 negatives, representing, as I believe they do, scenery which has never been photographed before, and amongst the boldest and most striking on the face of the globe’. |

|

|

A tea plantation of the Terai Tea Association, Darjeeling

1860s

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

General view of sailing ships moored on the Hooghly River at low tide along Custom House ghat, on the southern end of Fort William, Calcutta

1860s

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Labour and the early photographUnlike in our time, when it is sufficient to simply aim our cameras at a landscape and shoot its image, photography entailed a vast amount of labour-support in Bourne’s days. Vidya Dehejia writes, 'Samuel Bourne records that thirty porters accompanied him on his travels in the Himalayas in order to carry his ten-foot-high tent; 650 glass plates; two cameras and several lenses; numerous bottles of chemical solutions for coating, sensitizing, developing, and fixing the glass plates; funnels, pails, and baths in which the plates had to be immersed; and of course, his personal baggage.’ According to another historian, Bourne was an ‘obsessive, hard-driving, and sometimes abusive sahib’, who would resort to any means to make his porters obey his bidding and fulfil his objectives. Elsewhere, he did photograph the voluminous, though anonymous, labour that went into sustaining the economy of the Empire, with photographs of people working at plantations, mills or docks and ports across the subcontinent. These tend to ‘deny the native worker any real identity. They are present only insofar as they have been assimilated by Bourne into his overall compositions, thus symbolically reiterating their generally anonymous compliance with the demands of the Raj.’ |

|

Samuel Bourne was also conscious of the violence that photography sought to commit on Indian reality, subjected as it was, through British colonial photography, to increasing imperial control over its territories, people and culture. This makes him suggest that the camera wasn’t too far removed from the operative implications of weapons, especially guns that were loaded, aimed and shot: ‘From the earliest days of the calotype, the curious tripod, with its mysterious chamber and mouth of brass, taught the natives of this country that their conquerors were the inventors of other instruments besides the formidable guns of their artillery, which, though as suspicious perhaps in appearance, attained their object with less noise and smoke.’ Samuel Bourne’s contribution towards creating a balance between art and commerce in his photographs would leave a lasting legacy for many European and Indian photographers to follow. Bourne & Shepherd’s studio photographs helped to promote tourism in the country as well, by providing a unique insight into India's rich history and diverse cultures. The studio's picturesque landscape views and photographs of Indian nobility and British officials also helped to attract tourists to the subcontinent. |

|

|