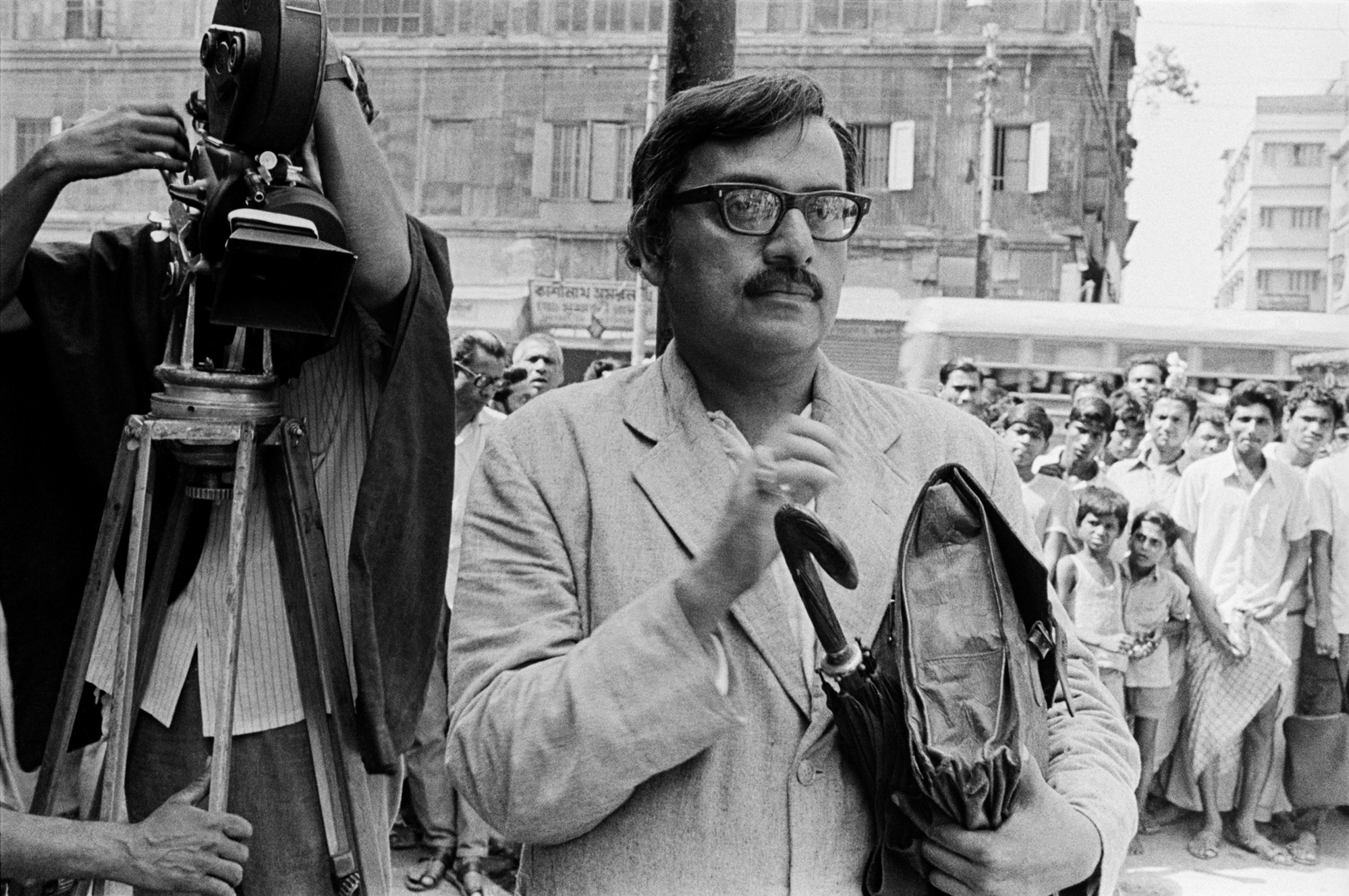

Boswell with a Camera: Nemai Ghosh's documents of cinemaMonami Goswami August 01, 2025 Nemai Ghosh’s photographs capture the fleeting, behind-the-scenes world of Satyajit Ray’s filmmaking through an aesthetic rooted in intimacy and process. Rather than focusing on iconic cinematic moments, Ghosh’s lens lingers on the quieter intervals—rehearsals, moments of waiting, and acts of collaboration—offering a textured view of Ray’s creative environment. His camera brings us unusually close to the filmmaker, positioning Ray within both the public sphere of the film set and the private spaces of his home. In fact, much of the enduring visual memory of Ray—as the introspective director in action or the private man at rest—has been shaped by Ghosh’s work. As visual culture theorist Ariella Azoulay argues, photography is fundamentally a relational act. In this sense, Ghosh’s role as an observer not only crafted Ray’s image but also influenced the very framework through which the filmmaker is remembered and enshrined in cultural memory. |

|

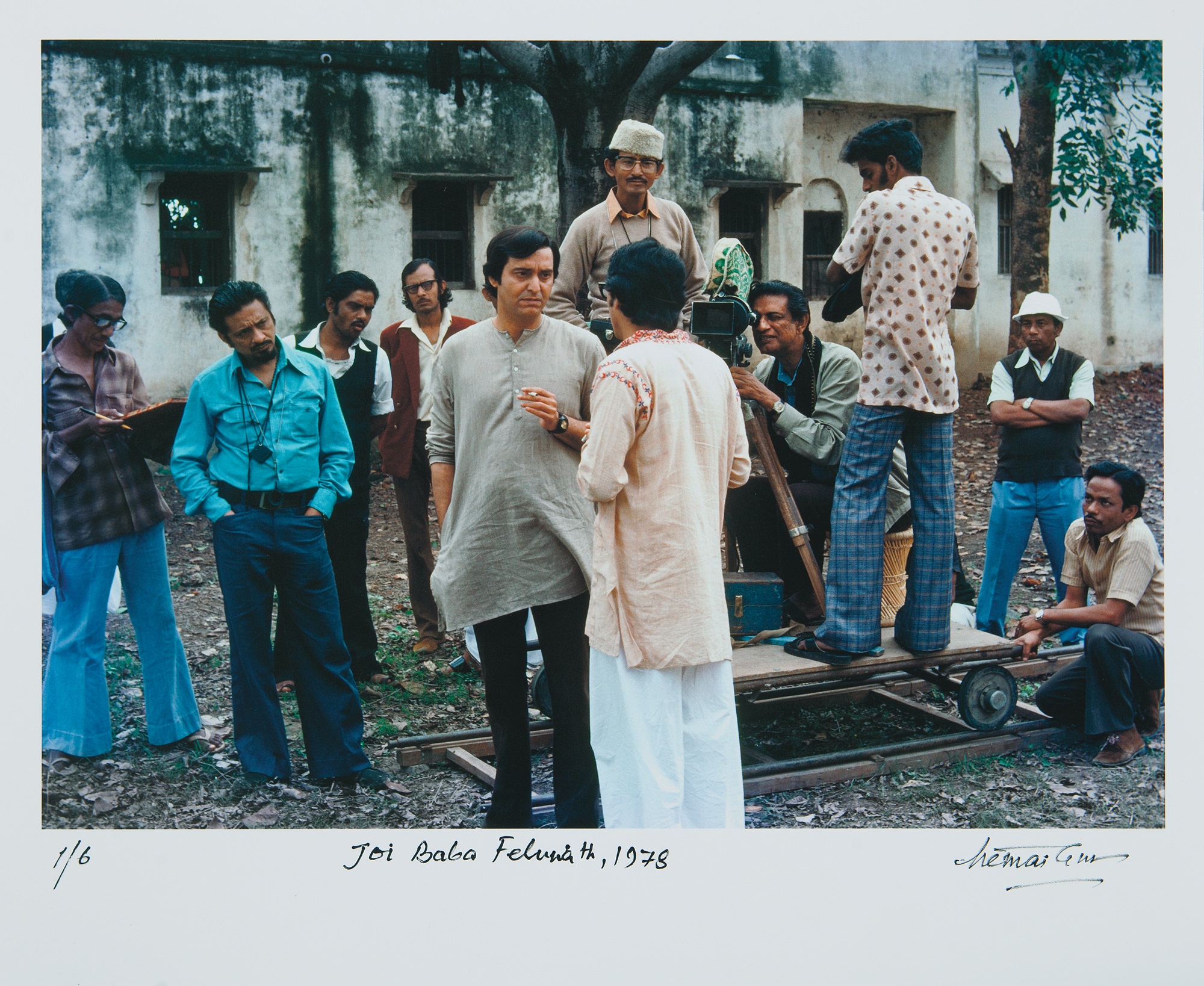

The exhibition ‘Light and Shadow: Satyajit Ray Through Nemai Ghosh’s Lens’ reconfigures these photographs beyond their immediate cinematic referents, reframing them as part of a larger photographic inquiry into time and the everyday poetics of artistic labour. While foregrounding Ray, Ghosh also captures actors in candid moments, camera operators, gaffers and spot boys which turn his photographs into archives of film history. |

|

|

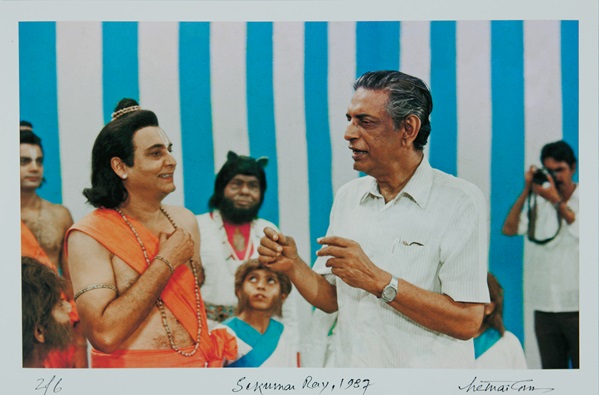

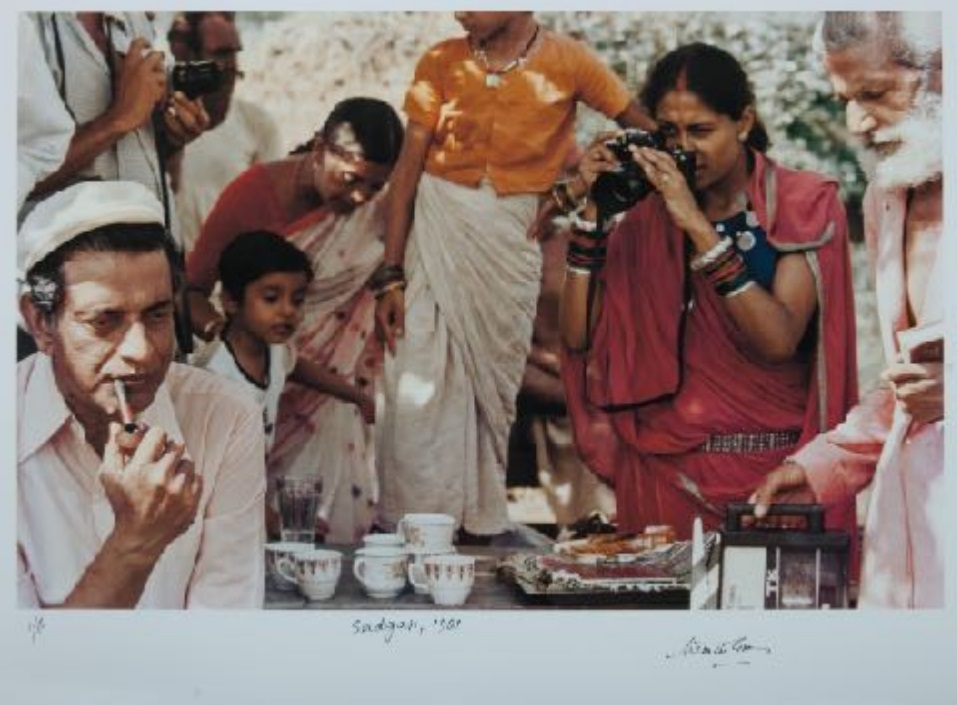

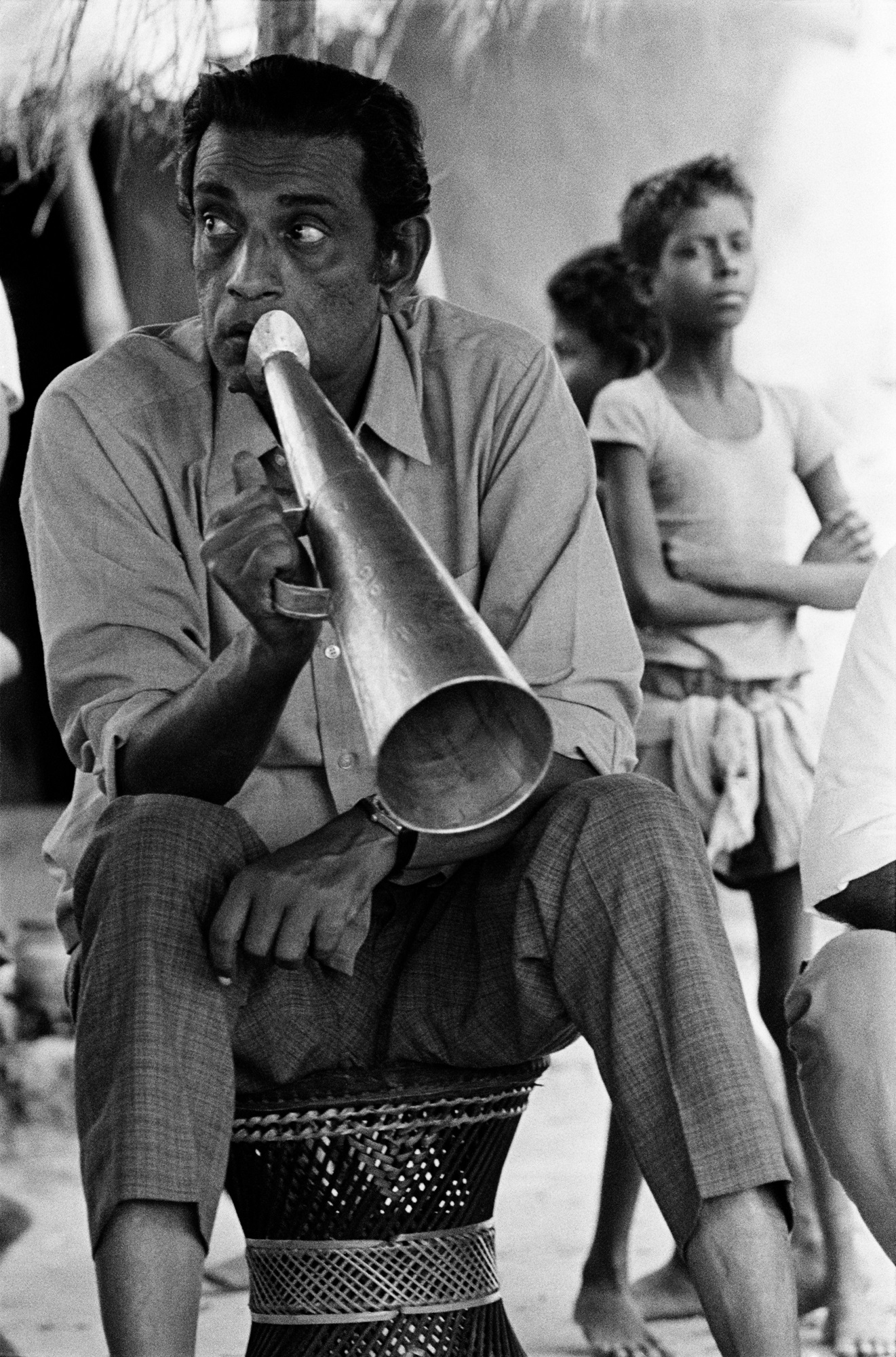

While Nemai Ghosh admitted of the influence of the French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson, he does not search for the ‘decisive moment’, even though we cannot discount the rich narrative that his photography captures. Additionally, Ghosh’s photographs are attentive to the quiet, human details that evoke memory and emotion. One such image captures actor Smita Patel photographing Satyajit Ray—a fleeting, intimate moment that speaks volumes. As historian Dr. Rudrangshu Mukherjee noted during the exhibition opening, ‘We would not know how fond she (Smita Patel) was of photography if Nemai Ghosh had not captured her in that moment.’ Through images like these, Ghosh preserves not just scenes, but relationships, gestures, and untold stories. |

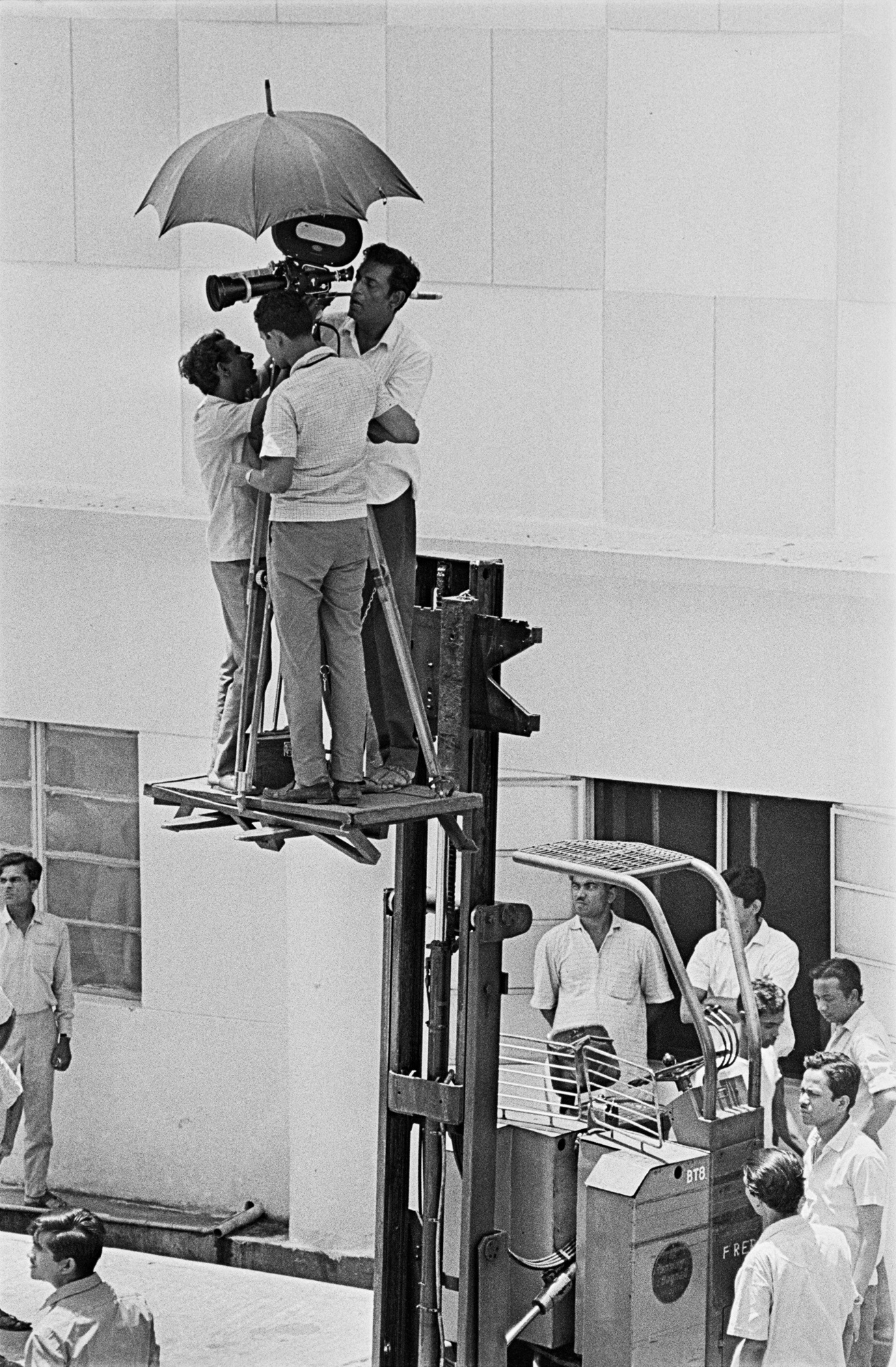

His photographs capture the camaraderie among those on set, the negotiations that underpin the filmmaking process, and the challenges of working on location. In doing so, they bridge cinema and photography, process and memory, the personal and the historical. The exhibition enacts a double gesture: it detaches the images from their original, functional context while simultaneously intensifying their archival significance, placing them at the intersection of documentation and art. |

|

|

Nemai Ghosh’s work must be understood within the context of the intellectual and political upheavals that shaped Bengal between the 1960s and 1980s—a time marked by a significant reimagining of modernity in the visual arts. The legacy of the Bengal Renaissance, the unrest of the Naxalite movement, and the city’s industrial decline created a complex backdrop for Satyajit Ray’s cinema, which aimed to balance a deeply humanist realism with a sharp sensitivity to the shifting social landscape. |

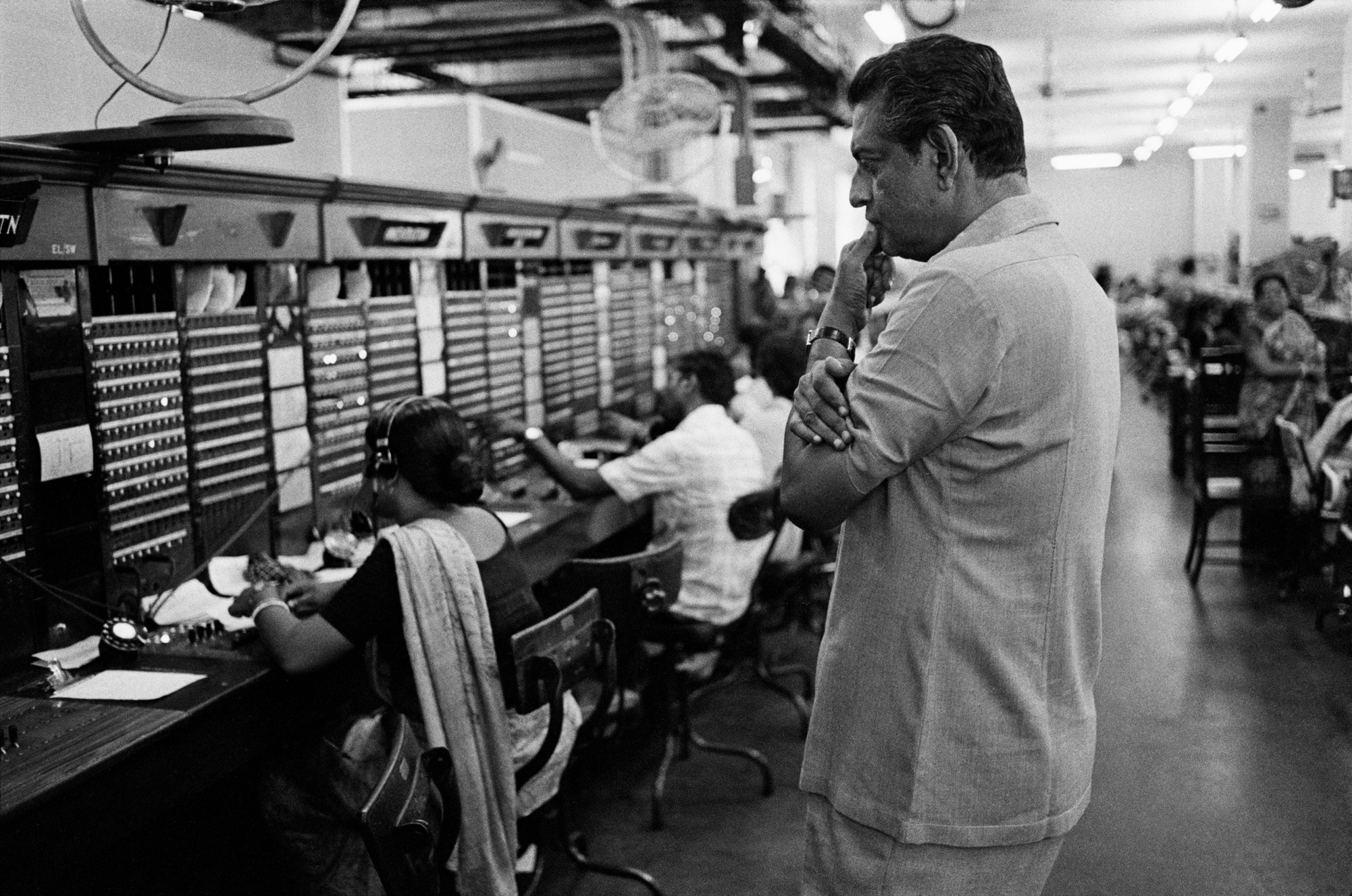

As an embedded photographer, Nemai Ghosh was far more than a passive observer—he was an active participant in the social and creative life of Satyajit Ray’s film sets. Actor Dhritiman Chatterjee, recalling personal memories of Ghosh, recounts how he once photographed a group of ‘hippies’ who appeared as bystanders in a film, capturing moments outside the scripted narrative. Ghosh often took photographs independently with actors, occasionally surprising them with spontaneous prints. His presence on set was so discreet and organic that he blended seamlessly into the film crew, a sharp contrast to the carefully composed publicity stills typical of mainstream cinema, which catered to the spectacle-driven economy of popular film. |

Ghosh’s photographs reveal the infrastructural fragility of parallel cinema, where filmmaking was an artisanal, almost intimate endeavor, sustained by personal relationships and a shared creative ethos. His camera lingered on moments of improvisation, rendering visible the informal practices, negotiations, and ephemeral gestures that shaped the final cinematic product but remained absent from the screen. Within the broader visual culture of the time, Nemai Ghosh emerges not simply as Ray’s documentarian, but as a creator of counter-histories—his photography forming a bridge between cinema and the socio-political undercurrents of the era. |

|

Nemai Ghosh’s visual language is inseparable from the aesthetic logic of Ray’s mise-en-scene, creating a photographic language that extended Satyajit Ray’s filmmaking. Ray’s cinema was marked by a restrained realism, a meticulous attention to spatial detail and an attempt to privilege observation over spectacle. Ghosh, by inhabiting Ray’s world so closely, internalised this sensibility and allowed it to inform his photographic practice. |

|

|

As both Dhritiman Chatterjee and Rudrangshu Mukherjee attest, Satyajit Ray served as a consistent mentor to Nemai Ghosh. Ghosh’s photographic sensibility closely reflects Ray’s visual language—marked by a preference for balanced yet understated compositions, the subtle use of natural light that illuminates rather than dramatises, and an emphasis on the everyday textures of life over theatrical flourishes. In his images from Ashani Sanket, for example, Ghosh mirrors the film’s visual austerity, capturing the stark expanse of the Bengali countryside in wide, contemplative frames that resonate with the film’s quiet poignancy. |

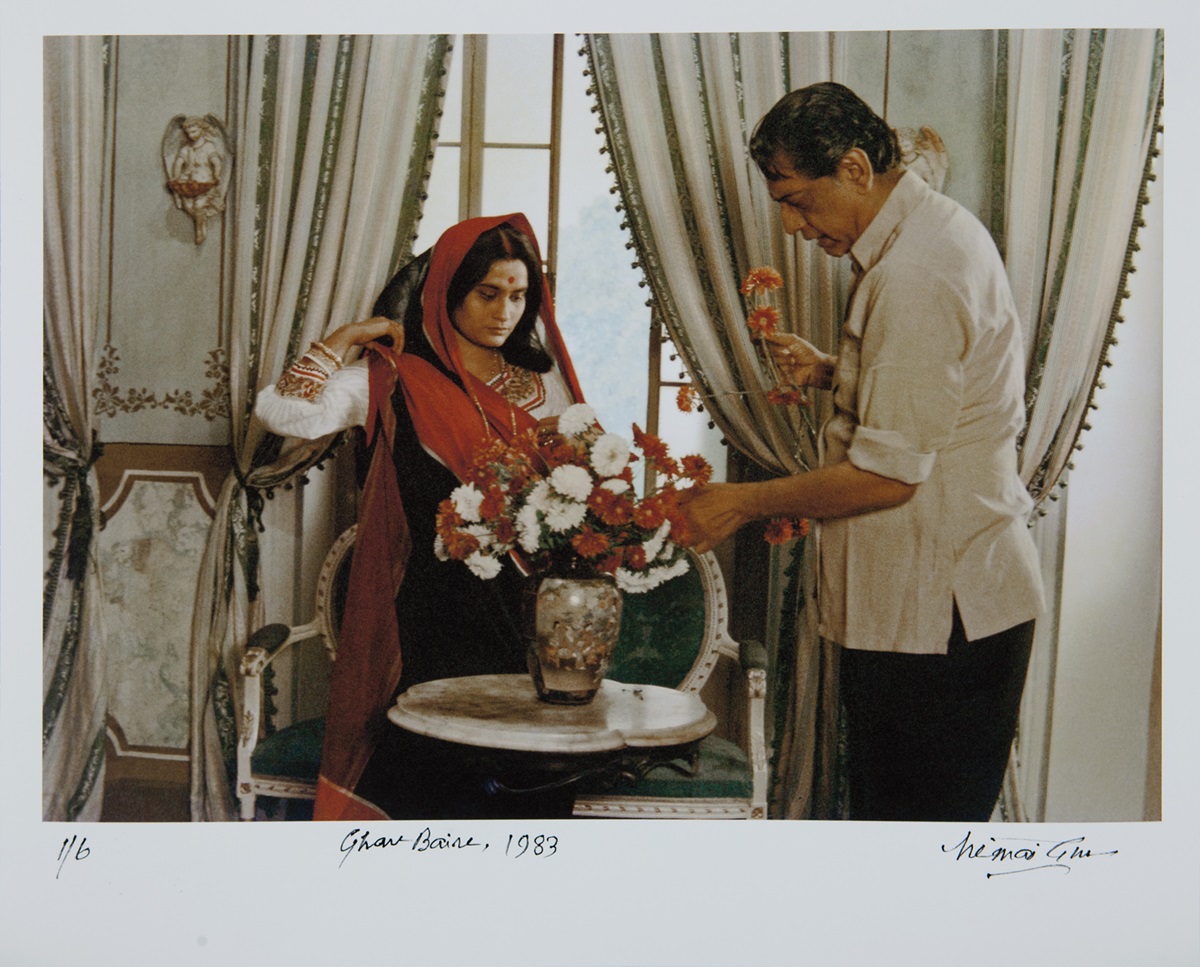

Similarly, in his photographs from Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne, despite the film’s fantastical nature, Ghosh avoids leaning into spectacle. Instead, he focuses on the quiet, grounded aspects of the production: props being assembled, actors dressed as spirits standing against bare studio backdrops, and moments of stillness between takes. His lens captures the behind-the-scenes reality with a restrained attentiveness, reflecting Ray’s own aesthetic sensibilities. This visual translation of Ray’s cinematic language into still photography reveals that Ghosh was not merely documenting the process, but absorbing and interpreting Ray’s visual grammar. As a result, his photographs become tangible records of Ray’s vision—evidence of the careful, deliberate construction of each film on set. |

Moreover, Ghosh’s sensitivity to gesture, waiting and process, reflects Ray’s own attention to what lies beyond the dramatic climax, a philosophic vision that put Pather Panchali on the map of world cinema. Just as Ray would dwell on pauses, on characters caught in reflection or silence, Ghosh too captures these moments when the film camera was not rolling, to show actors preparing for a shot, Ray arranging flowers in a vase, crew members resting, the director scribbling notes. |

|

|

The shared aesthetic is also reflected in their use of chiaroscuro. Ray’s interiors often featured soft gradations of light that enhanced mood and atmosphere, as seen in Shatranj Ke Khiladi, Ghare Baire, and Hirak Rajar Deshe. Ghosh’s stills echo this same tonal subtlety. In this way, Ray’s influence on Ghosh extended beyond subject matter; it offered a visual and temporal sensibility that reshaped Ghosh’s approach to photography. He inherited Ray’s commitment to realism, his focus on process, and his deep respect for the dignity of everyday life. |

|

The afterlife of Nemai Ghosh’s images inevitably prompts questions of authorship: can his photographic body of work ever be separated from the gravitational orbit of Satyajit Ray, or is his legacy intrinsically entwined with that of the filmmaker? On one hand, Ghosh’s photographs have become the most enduring visual record of Ray’s working life, shaping how audiences, scholars, and cinephiles continue to envision the auteur—not as a remote, mythic figure, but as a man deeply absorbed in his craft, embedded within a collaborative and familial ecosystem. Ghosh’s photographic practice can also be understood through Jacques Derrida’s concept of ‘archive fever,’ where the act of preservation is inseparable from the act of construction. The Ray we inherit today is already filtered through Ghosh’s selective gaze. He does not merely document Ray’s cinema; he constructs a parallel visual narrative—one that both reflects and transcends the films themselves. His photographs transform the still image into an active site of historiography, rather than a passive record. Through his lens, we glimpse the multifaceted labor of filmmaking: Ray’s notebooks, his sketches, his working methods—all the processes that animate cinema from within. The enduring resonance of Ghosh’s work lies in this dual function: preserving the mystique of Ray’s creative universe while simultaneously grounding it in its material reality. In doing so, Ghosh transforms what might have been fleeting into a lasting visual archive—one that continues to shape how we remember both cinema and its history. |

|

|