Bombay through the eyes of European ArtistsAnkan Kazi November 01, 2023 As one of the three major colonial cities that thrived under the British East India Company—and subsequently, the British crown—Bombay (now Mumbai) is one of the great megalopolises of the Indian subcontinent. The British Raj received the islands that now form Mumbai from Portuguese settlers in 1611, due to a royal marriage between Charles II of England and Catherine of Braganza, daughter of King John IV of Portugal. The city was consolidated over the course of the eighteenth century, and its access to global trade routes helped it grow over the following centuries as well, leading some to describe it as the 'door of the East with its Face to the West'. How did European artists view this growing city? |

Unidentified artist

Sewri Bay

c. 1830, Watercolour and gouache on paper pasted on paper, 33.0 x 49.5 cm.

Collection: DAG

|

The story of European artists developing techniques for representing the city of Bombay evolving over the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, especially since the ‘cotton boom’ of the 1860s, is a story of artists progressing from mythic distance to intimate familiarity. Starting with representations of Mumbai and its environs’ claims to a mythic past, to frank depictions of the sources of its temporal glory—especially its docks and ports—Mumbai has provided a shifting landscape of economic, social and visual formations that have attracted resident Europeans and travellers since the earliest period of its existence and growth as one of the quintessential colonial cities of India: from early Portuguese settlements to British consolidations, in partnership with Indian entrepreneurs to an extent not readily seen even in the other colonial cities of its time. |

|

|

John Strickland Goodall

A Busy Street Scene Near Jama Masjid Mosque, Bombay

Ink, graphite and gouache on paper/pasted on paper and pasted on Masonite board, 28.4 X 43.2 cm.

Collection: DAG

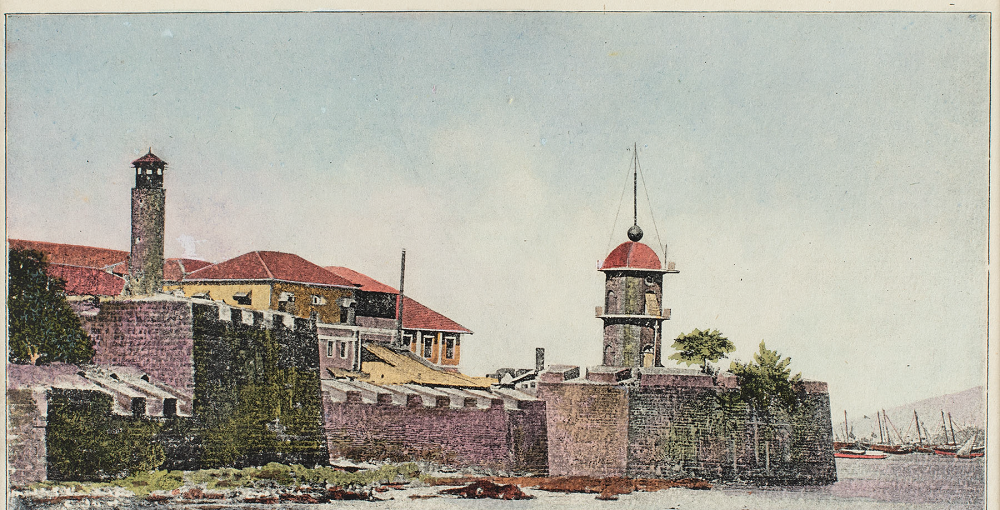

Unidentified Artist

Untitled (Bombay Castle, Behind the Town Hall)

1626, Hand tinted on mechanical reproduction print on paper, 14.2 X 24.1 cm.

Collection: DAG

As biographers like Gillian Tindall have described the complex mix of cultures and societies in Bombay’s colonial melting pot: 'Like London, like Paris or New York or pre-war Alexandria, Bombay contains not just many different social worlds but whole solar systems of different societies moving separately and intricately over the same territory. Ever since its insignificant and hesitant beginnings it has acted as a draw for people of so many races and languages, Indian, Middle Eastern and European, that there is no one tongue in general use there. For a while the largest city east of Suez till you came to Tokyo, and the largest in the British Empire after London, Bombay has always just missed being a world capital.’ |

|

Many of the earliest images of places in or near Bombay were included in travelogues written by some of the most well-known travellers to India, such as Francois Bernier, Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, Niccolao Manucci or Philippus Baldaeus, whose books were illustrated with woodcuts and engravings. According to a historian, ‘These prints were based upon drawings and maps, probably made by the authors themselves or their fellow-travellers. Sometimes, however, they derived from prints already published. Although some of the topographical illustrations were accurate, much was left to the engravers’ imagination, and fanciful embellishments occurred in many of these early prints.’ |

|

|

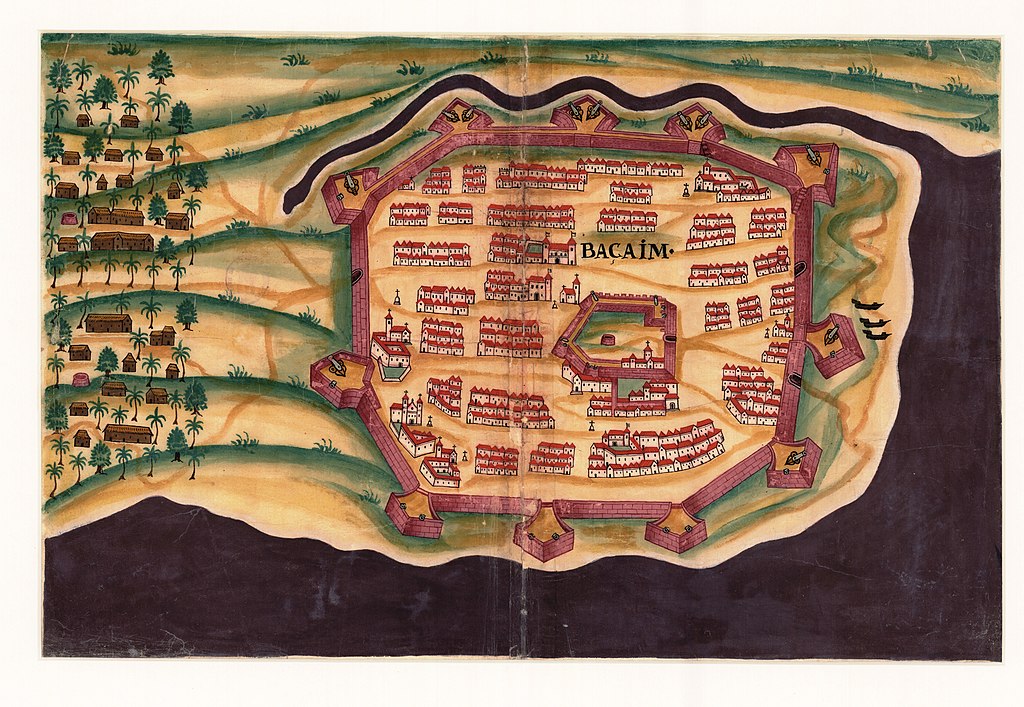

Old Portuguese map of Bassein/ Vasai

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Aside from engravings and printed images of architectural views, artists and cartographers also made maps that helped consolidate the idea of Bombay, put together from disparate islands that were formerly in the possession of the Portuguese. A skilful water colourist was an asset for the British East India Company’s administrators and military officials, ‘for’, as a historian of Bombay writes, ‘it ensured the production of accurate visual records for a reliable corpus of military intelligence.’ Military academies in Britain would regularly employ skilled watercolourists to teach potential candidates who were about to leave for service in Inda. |

|

Besides sensitive information—which were also packed into maps, and later, photographs—these images also help document the infrastructural growth of the city, giving us visual access to its lived spaces of work and leisure. Many of these buildings, streets, walls (that surrounded the colonial city towards the south of modern-day Mumbai) are not visible today, leaving these images as the only sources for reconstructing the look of Bombay in the past. However, many European artists made views of colonial cities and spaces without actually travelling to them, relying on literary descriptions and reports; and this should make us wary about treating these images as historical documents that can offer us a transparent view into those times and spaces. They were all shaped by political considerations, romantic fantasies about the ‘orient’ or the growing British Empire, and emphases on various details that were pertinent for contemporary viewers. Over time, as the British and other Europeans on the island became more familiar with the landscape, views were not restricted to shoreline glimpses of ports and batteries, but also started to include the architecture and the ‘diverse cast of colonial residents who inhabited the growing colonial city’. Many of these artists are unnamed or unidentified in the archives; however, we do know the names of a few enduring hands that shaped the views of Bombay. |

|

|

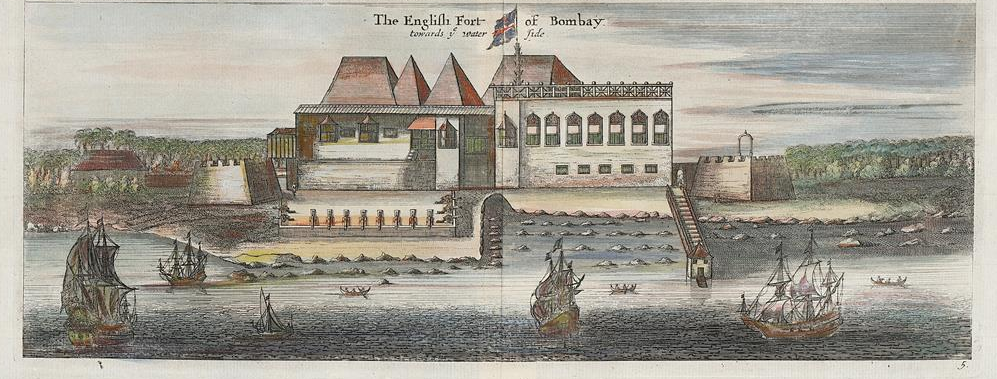

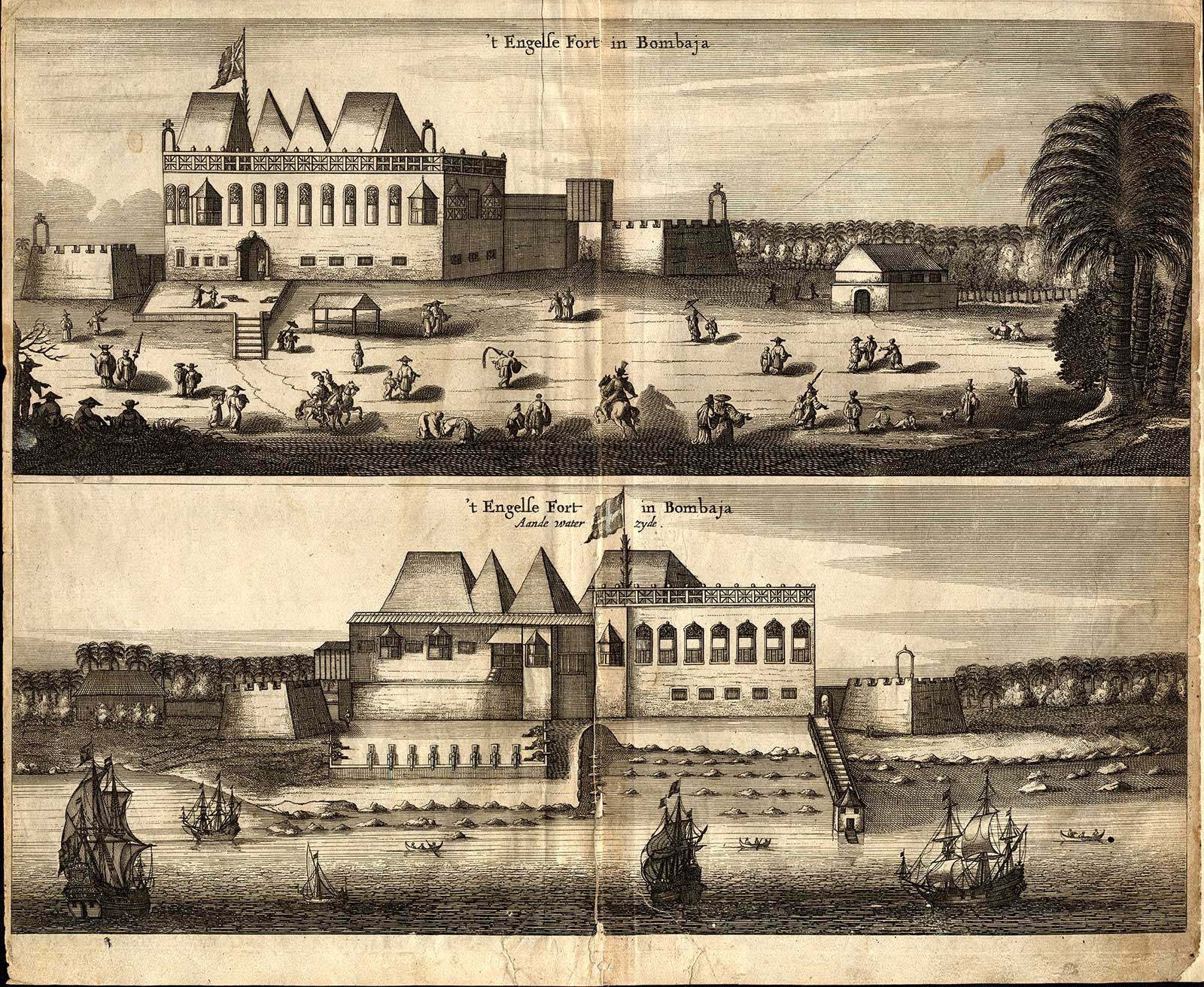

Philippus Baldaeus

The English Fort of Bombay

1704

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Philippus Baldaeus (1632-1672) was a Dutch missionary, theologian, and historian who lived in the seventeenth century. He is best known for his comprehensive account of the Dutch East India Company's activities in Sri Lanka and the Malabar Coast of India, titled A True and Exact Description of the Most Celebrated East India Coasts of Malabar and Coromandel and also of the Isle of Ceylon, published in 1672. Baldaeus included illustrations of Bombay (then known as ‘Bombayo’) in his book. These illustrations typically depicted scenes of the city's landscape, architecture, and daily life during the seventeenth century, providing valuable historical insights into what Bombay looked like during the Dutch colonial period. The English Fort of Bombay is an engraving created by him, showing the fort of the English colonising forces in Bombay. The directors of the British East India Company ordered the construction of a custom house, warehouse and quay around the Portuguese settlement on Bombay Island in 1668. In the 1670s, under the governorship of Gerald Aungier, Bombay was developed as a trading centre. His plans for a walled town with bastions were implemented by a later governor, Charles Boone. By 1710, the fort included a magazine, quarters for soldiers and two water tanks. |

|

There were contending accounts of the charms presented to a first-time viewer of the Bombay harbour, as they approached the shore, with some preferring the ‘splendours of Chandpaul Ghaut in Calcutta’. However, as an anonymous writer travelling towards Bombay in 1838 noted later for the Asiatic Journal: ‘Bombay harbour presents one of the most splendid landscapes imaginable. The voyager visiting India for the first time, on nearing the superb amphitheatre, whose wood-crowned heights and rocky terraces, bright promontories and gem-like islands, are reflected in the broad blue seas, experiences none of the disappointment which is felt by all lovers of the picturesque on approaching the low, flat coast of Bengal with its stunted jungle. A heavy line of hills forms a beautiful outline upon the bright and sunny sky; foliage of the richest hues clothes the sides and summits of these towering eminences, while below, the fortress intermingled with fine trees and wharves running out into the sea present altogether an imposing spectacle on which the eye delights to dwell.’ |

|

E. Goodall Bombay Harbour :- Fishing Boats, in the Monsoon 1844, Engraving on paper, hand-tinted with pastel, 15.2 X 18.3 cm. Collection: DAG |

George Lambert and Samuel Scott

Bombay

1731, Oil on canvas, 81 x 132 cm.

Image Courtesy: Public Domain

George Lambert and Samuel Scott never actually visited India themselves, but they based their depictions of the country on written accounts and other sources. It is speculated that their view of the Bombay port may have been informed by Baldaeus’ engravings. As Romita Ray writes: ‘Not surprisingly, the sea also shaped the vantage point of George Lambert and Samuel Scott’s view of Bombay displayed in 1732 at the Company’s newly rebuilt headquarters in Leadenhall Street in London. Here, the eye sweeps across the harbour where it encounters a phalanx of battling ships, their cannons booming and flags aflutter as they ferociously guard the Company’s territorial possessions. A contested zone where maritime power was tested time and time again, the sea shored up the Company’s transcontinental trade networks that wove their way though Saint Helena, Cape Town, Bombay, Tellicherry, Madras and Calcutta whose coastlines appear in five other canvases painted by Lambert and Scott—pictures that were displayed alongside the artistic duo’s views of Bombay at the East India House.’ |

|

Thomas Daniell and his nephew William Daniell, both renowned English landscape artists, visited Bombay during their extensive travels in India in the late eighteenth century. Their artistic approach involved a combination of detailed sketches and the use of aquatint, a printmaking technique that allowed them to create finely detailed and tonally rich prints. The Daniells made on-the-spot sketches of the landscapes, cityscapes, architecture, and people of Bombay. These sketches served as the foundation for their later artworks. |

|

|

Thomas and William Daniell

Entrance to a cave on the island of Elephanta

Image Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Thomas and William Daniell

Part of the Interior of the Elephanta

1800, Engraving

Collection: DAG

|

The finished and coloured aquatint prints were published in series. One of their notable works is the series titled Oriental Scenery, which featured views of Indian landscapes, cities, and historical sites, including Bombay. These prints were highly influential and provided Europeans with some of the earliest visual representations of India. The Daniells' meticulous approach to capturing the essence of Bombay and other Indian cities in their aquatint prints not only documented the landscape and architecture but also contributed significantly to the European understanding of India during that time period. Their works remain valuable historical and artistic resources today. |

|

William Simpson (1823-1899) was a renowned Scottish artist and war correspondent known for his detailed and vivid illustrations depicting various conflicts and landscapes during the nineteenth century. One of his notable journeys took him to Bombay, where he captured the essence of the city through his artistic lens. |

|

|

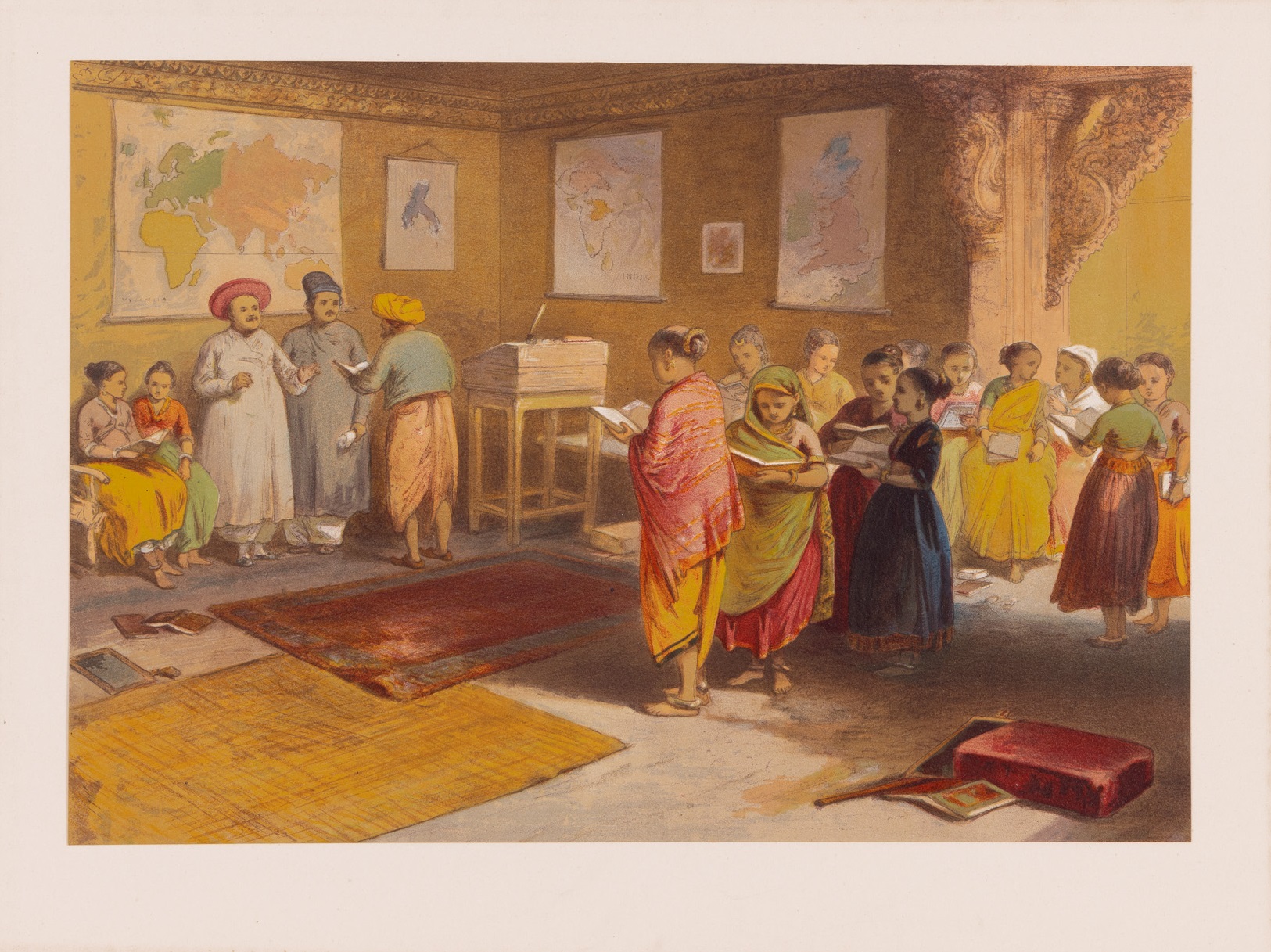

William Simpson

Bombay Girls School

Chromolithograph on paper/pasted on paper, 24.6 X 35.6 cm.

Collection: DAG

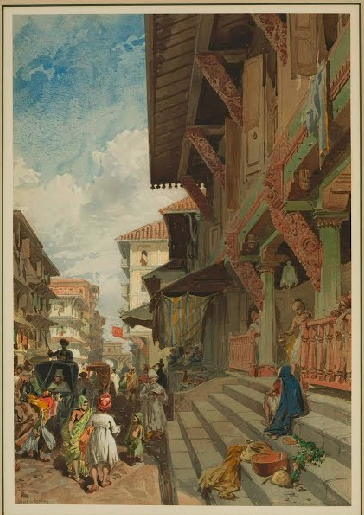

William Simpson

A Street Scene in Bombay

1862-1867, Chromolithograph, 50.2 x 35.6 cm.

Image Courtesy: Public Domain

Simpson's visit to Bombay occurred during a time of significant transformation in the city's history. It was, by then, a thriving hub of trade and commerce under British colonial rule. Simpson's keen observational skills and artistic talent enabled him to document the city's vibrant culture, diverse population, and architectural marvels. During his stay in Bombay, Simpson created a series of exquisite illustrations that showcased the city's unique blend of traditional Indian and colonial British influences. His works captured the bustling bazaars, ornate temples, colonial buildings, and the bustling port, all of which were integral parts of Bombay's identity at the time. Especially fascinating is a print titled Bombay Girls School, where he depicts a typical school day for girls who were increasingly finding themselves the object of educational reform, spearheaded in places like neighbouring Poona (now Pune) by social reformers and anti-caste activists like Jyotirao and Savitribai Phule. |

|

European artists would continue to visit or live in Bombay into the twentieth century, with a last great wave of immigration taking place in the 1930s and ‘40s, when several people sought to escape a fascist, and then war-torn, Europe. Among these refugees were patrons, artists and collectors like E. Schlesinger, Rudolf von Leyden and Walter Langhammer. Langhammer was an Austrian painter, born in Graz in 1905. He studied at the Academy of Fine Arts, Vienna and married Käthe Urbach, who came from a Jewish family of Vienna. He moved to India just before the Second World War broke out to escape the Nazis in Austria. He was an art student at the time Oskar Kokoschka was teaching at the Viennese Academy. |

|

|

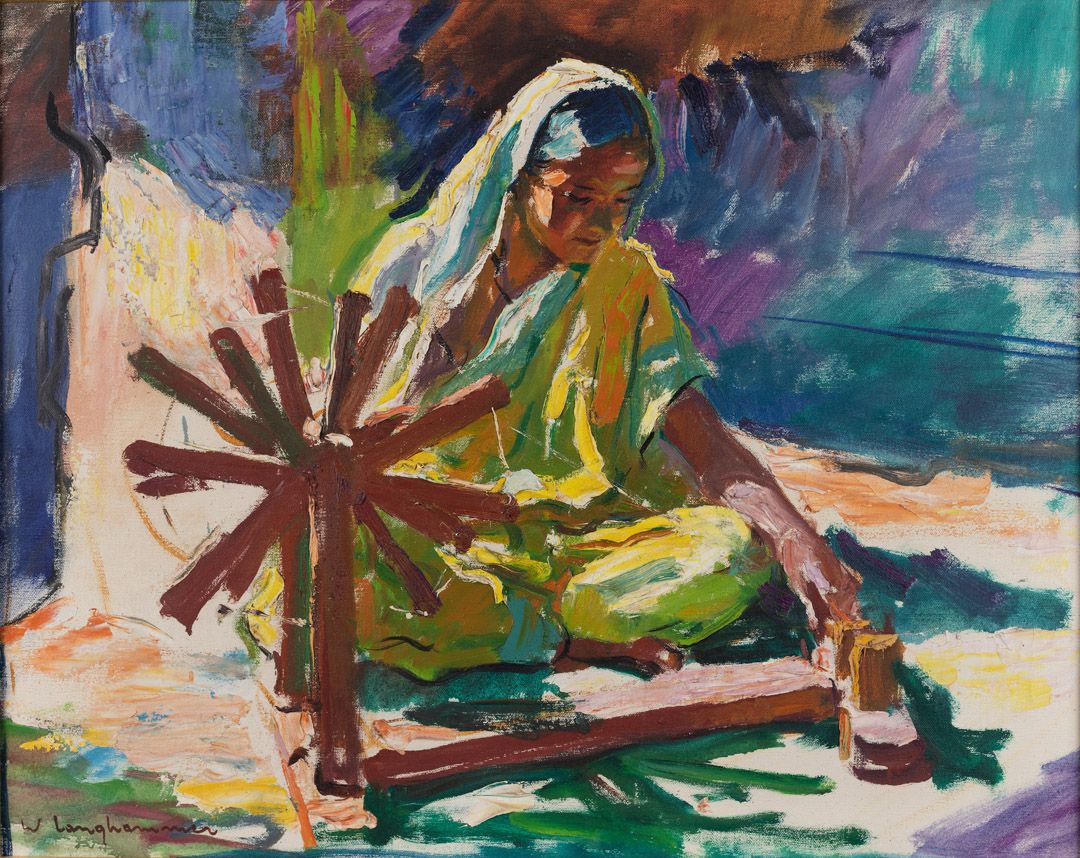

Walter Langhammer

Untitled (Portrait of a Woman at a Spinning Wheel)

Oil on canvas, 57.7 x 71.1 cm.

Collection: DAG

Walter Langhammer

Untitled

Oil on hardboard, 22.1 x 45.0 cm.

Collection: DAG

Walter Langhammer (1905-1977) was one of the foremost patrons, mentors and critics of the Bombay Progressive Artists' Group. Through Langhammer, who held lavish parties and salons at his residence following Bombay Art Society shows, early Indian progressive artists like M. F. Husain and S. H. Raza were exposed to the influence of modernist European art that was being systematically denigrated by the Nazi regime. He became chairman of the Bombay Art Society in 1938 and was a committee member of the diamond jubilee exhibition of the Society from 1952-53. Known primarily as a landscape painter, Langhammer made several views of Bombay harbour as well, an early (colonial) theme that, in his hands, found some sun-baked warmth and a sense of having been lived in, and not merely seen from a distance. In some of his other works, such as an untitled portrait of a woman at a spinning wheel, we see a European artist making explicit political gestures towards identifying with Indian nationalism. A process that arguably started with teachers like E. B. Havell and Gladstone Solomon at colonial art institutions, came full circle with this group of émigré influencers of Indian modern art—resulting in the making of an art that became ‘Indian’ by embracing the best of global art as well. |