|

Artists' Collections Between text and image: Hiran Mitra's art and collectionAnkan Kazi and Soumava Das July 01, 2023 Hiran Mitra (b. 1945) is an artist, writer and illustrator. A graduate of Kolkata’s Government College of Arts and Crafts, he has forged one of the more unique careers in Indian and Bengal art in the second half of the twentieth century and the beginning of this present one. Often described in shorthand as a ‘postmodernist’, due to his efforts to absorb influences from performance, theatre, cinema and the action painters of the west, Mitra’s own art and his collection of art and craft objects by his teachers, peers and friends constitute a remarkable personal archive that is inflected by his vision of the world as a flashing apparition between image and text. We travelled to his house, located in a pocket of Kolkata’s Tollygunge neighbourhood, to learn about his collection and practice. |

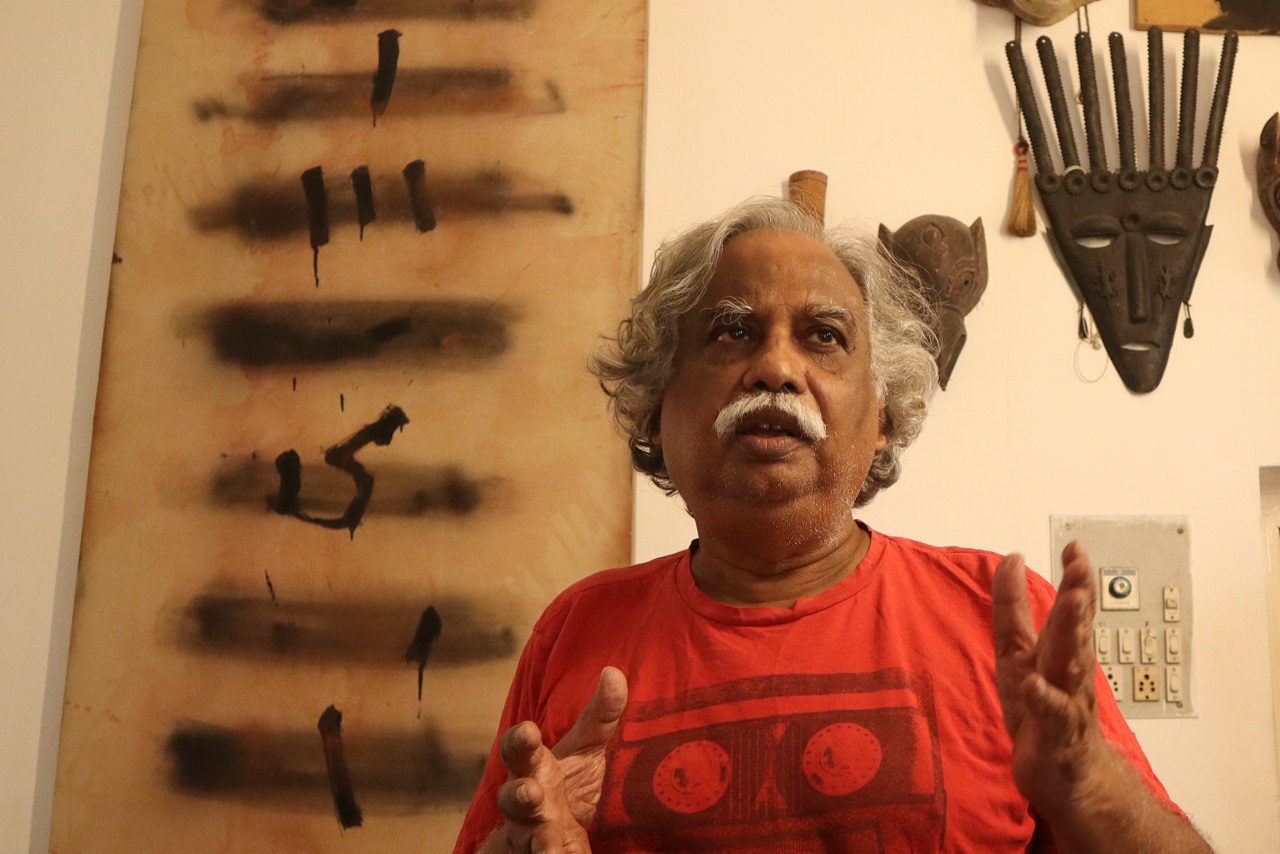

Hiran Mitra at his Tollygunge residence

|

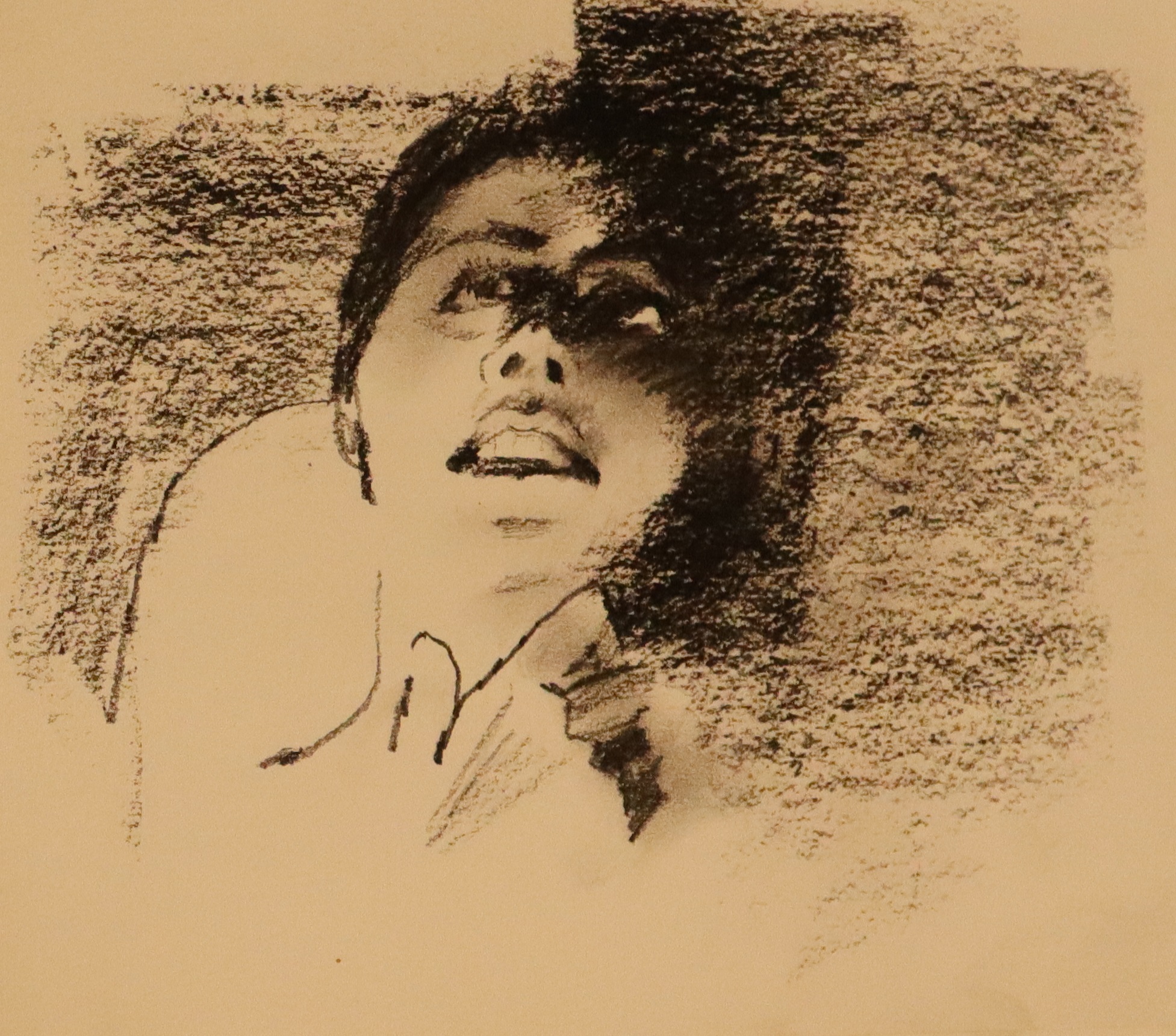

Mitra’s works are characterized by experimentations with line, colour and movement. He writes about his lines as dividing agents and traces for movement. Colour adheres to line, ‘expressing a romantic act of consummation’. |

|

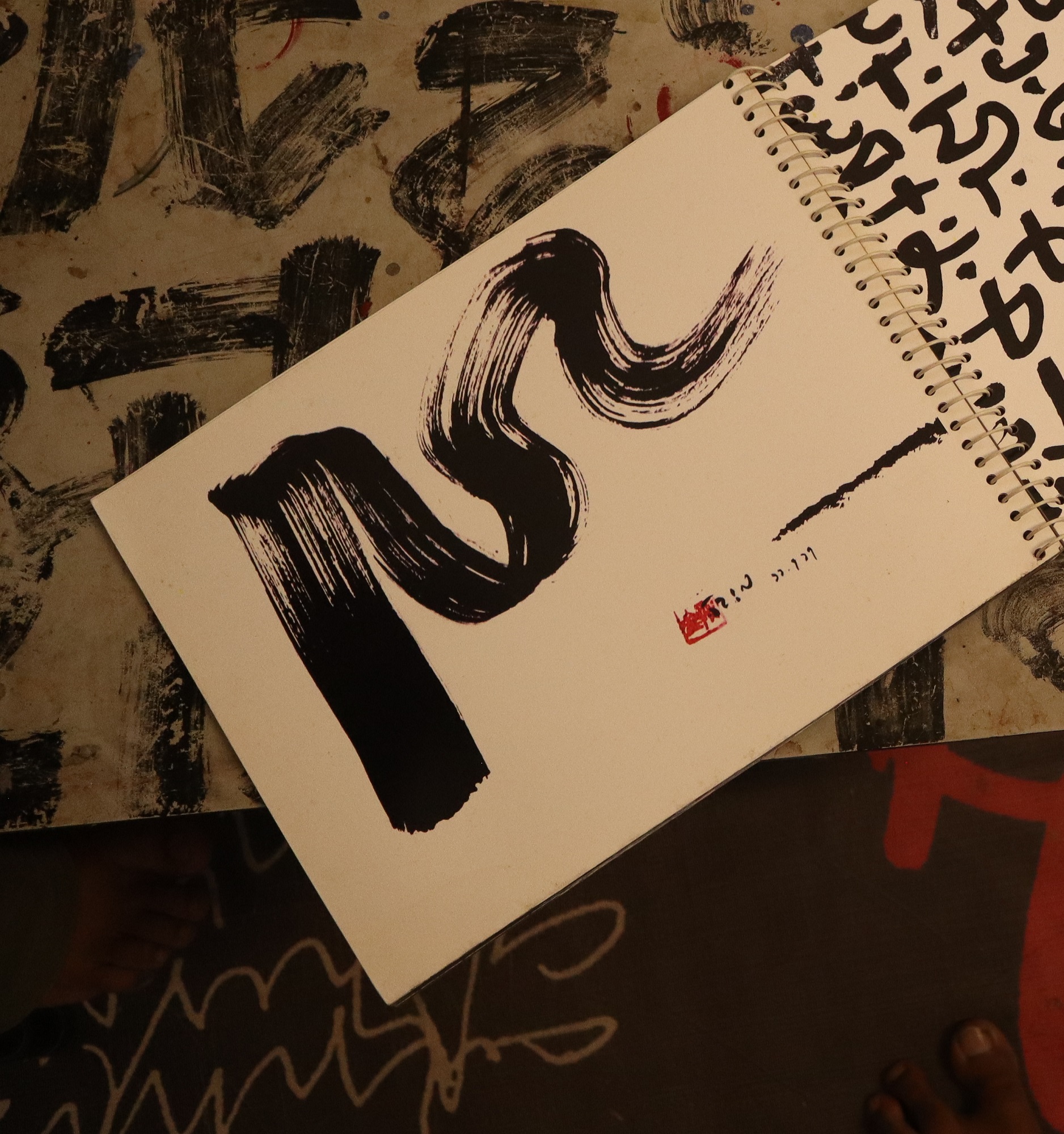

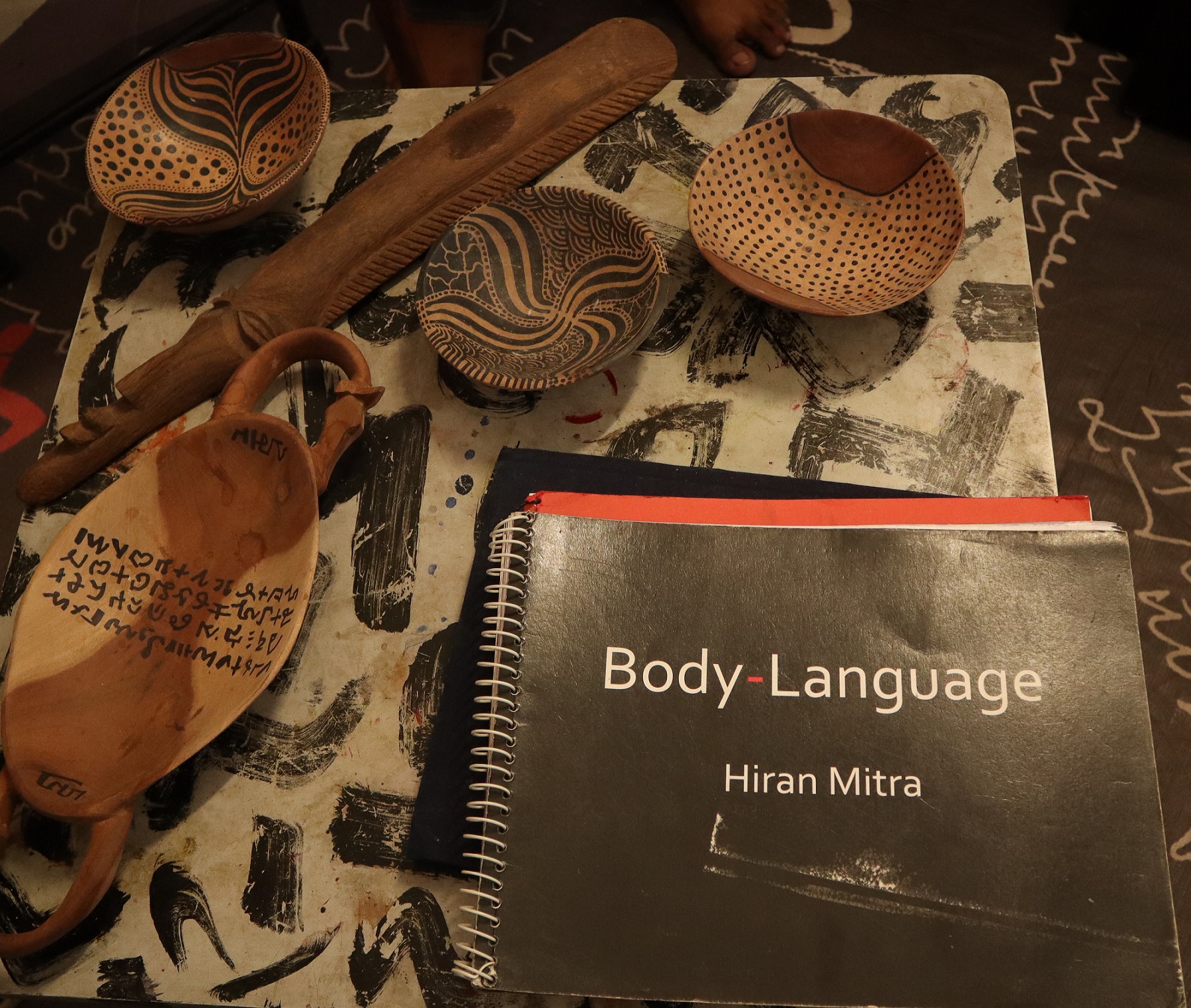

Bag designed by Hiran Mitra for an exhibition |

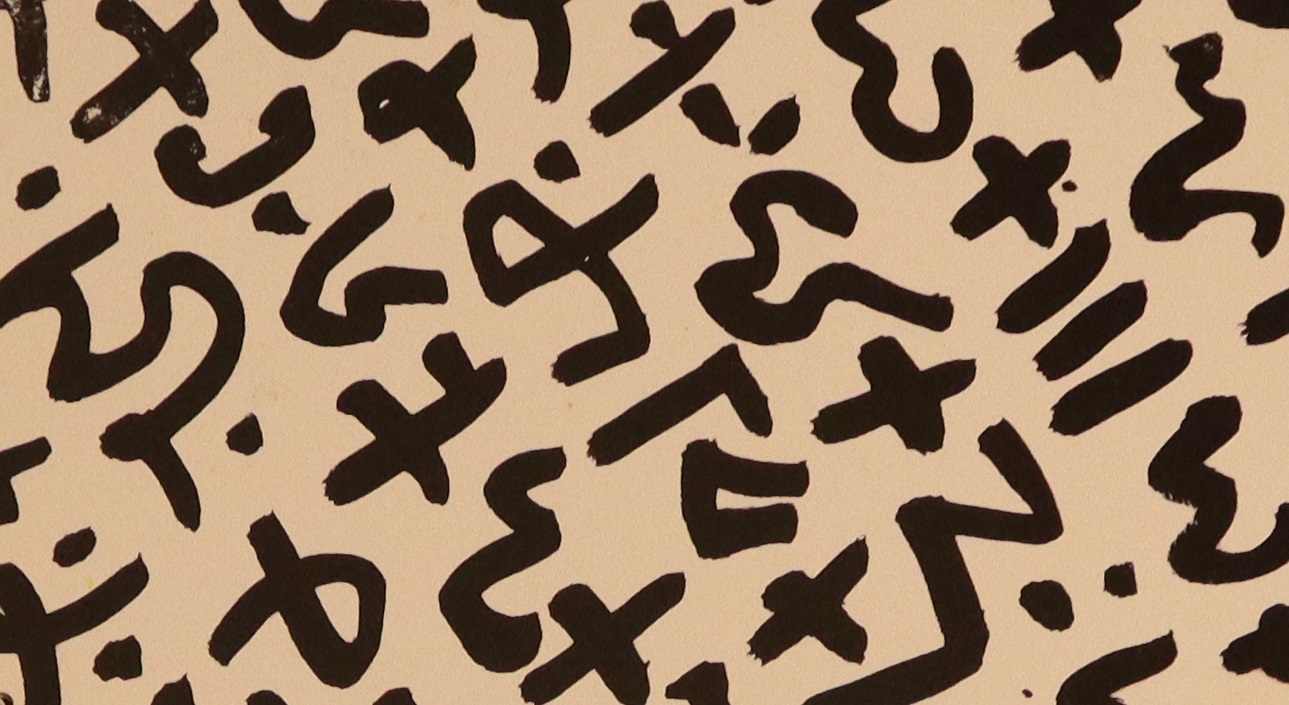

His line-works tend to hover between a primordial prototype of quasi-hieroglyphic writing and identifiable letters from a familiar alphabet. They aren’t just calligraphic experiments, but ways to suggest a literal search for meaning, as if searching for a new way to write images. As words become images and images made to yield to words, Mitra’s work searches for new myths and new languages of discovery and innovation, instead of practicing a mode of revivalism. |

|

‘The private worlds of image and language run parallel to each other. In apparent silence against all considerations of employability. But they keep us going, storing all our vital energy in its reserve. Its presence is almost imperceptible in the world of books. They are not to be found in exhibition rooms, pages of books, torn fragments of manuscripts, pictures, sculptures. They are struck silent, stuck in a strange phase of creation, like a surprising line of poetry or prose—’ from Bhashaye Chitrakolpo, Chitra-anushongo (Image-thinking and image-relations in language) |

|

|

A bust of Dipak Majumdar

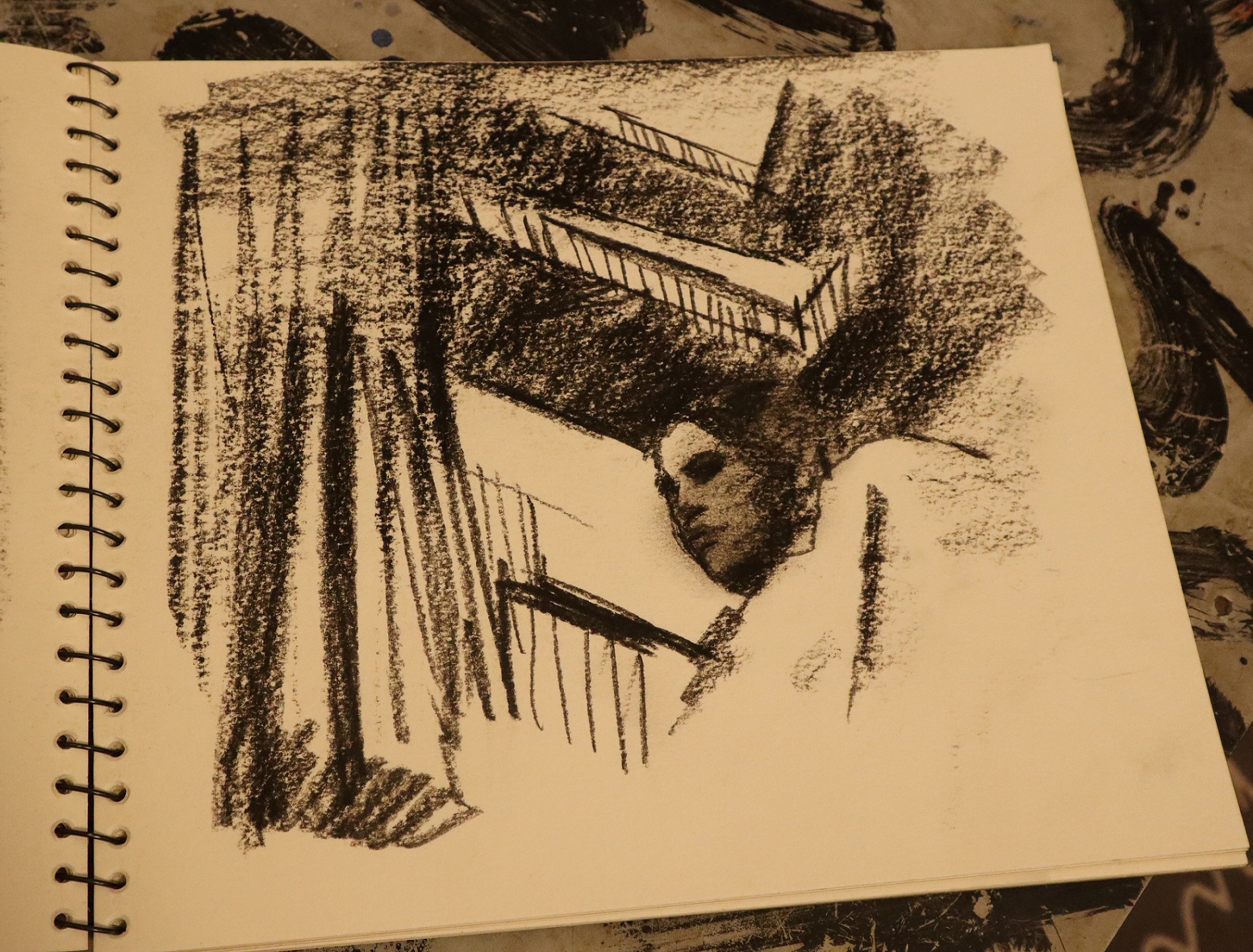

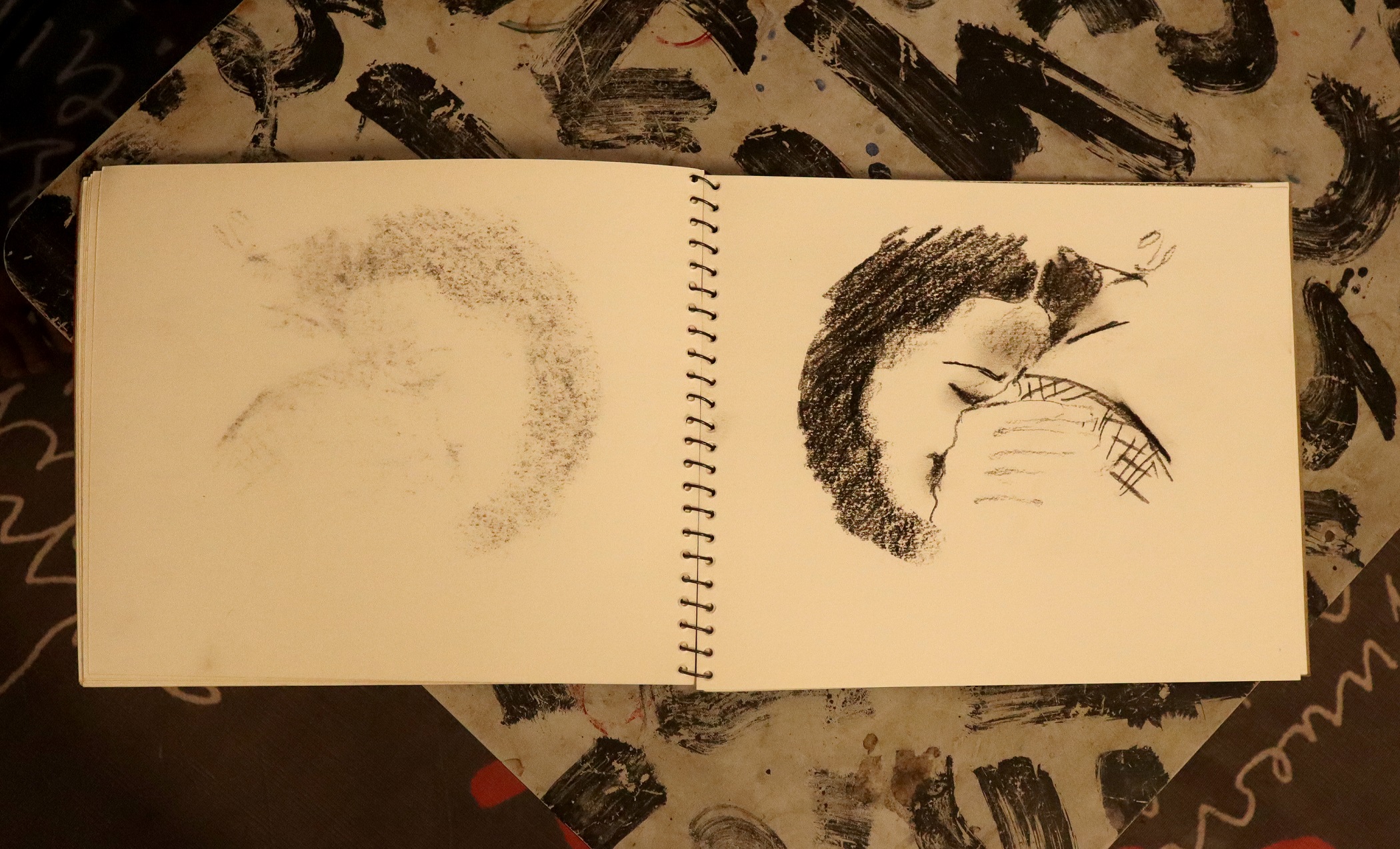

The DocumentA significant part of Mitra's practice consists of what he terms 'documentation'. By documentation, he refers to an intricate practice of recording his own acts of perceiving cultural texts, including plays and films. From his towering stack of notebooks filled with such documentary sketches we saw one that he made around 1990, 'documenting' scenes from Ritwik Ghatak's iconic film Meghe Dhaka Tara (1960). He said he was tasked with documenting Ghatak's films by his friend, the poet (and one of the founders of the Bengali literary journal, Krittibas) Dipak Majumdar. Initially, he would sketch frames from the films as he saw them in darkened theatres, but eventually, with the advent of video tapes, he would use the technology to pause on frames that made a singular impact on him or drew a reaction from the audience he was watching it with. |

|

For his experimental practice with drawing and ink-based washes he has drawn not only from the tradition of Indian manuscript illustrations, Islamic calligraphy and East Asian landscape drawing, but also western art traditions like the ‘hypergraphics’ produced by the French lettrists of the early twentieth-century. |

|

|

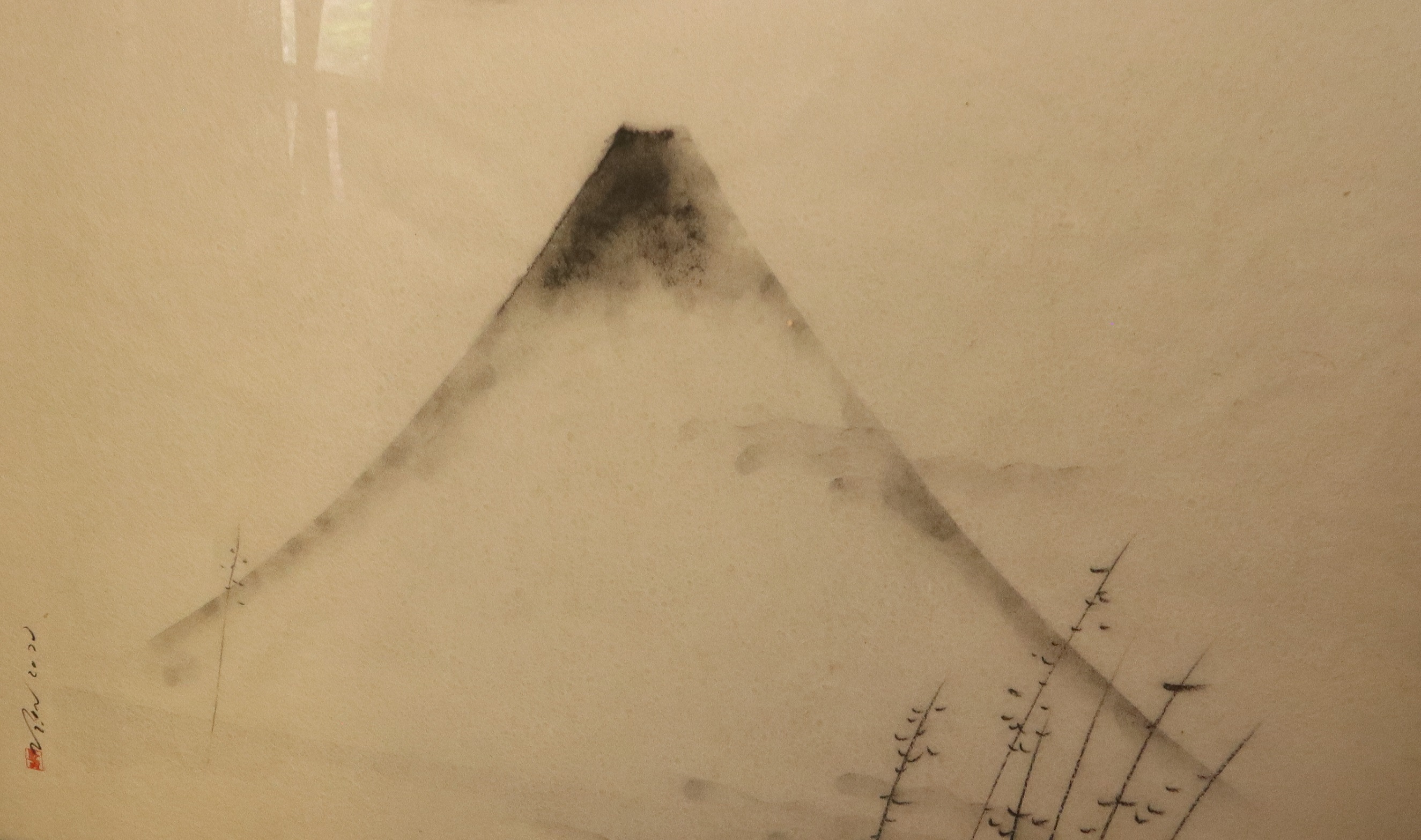

Gopal Ghose

Gopal Ghose

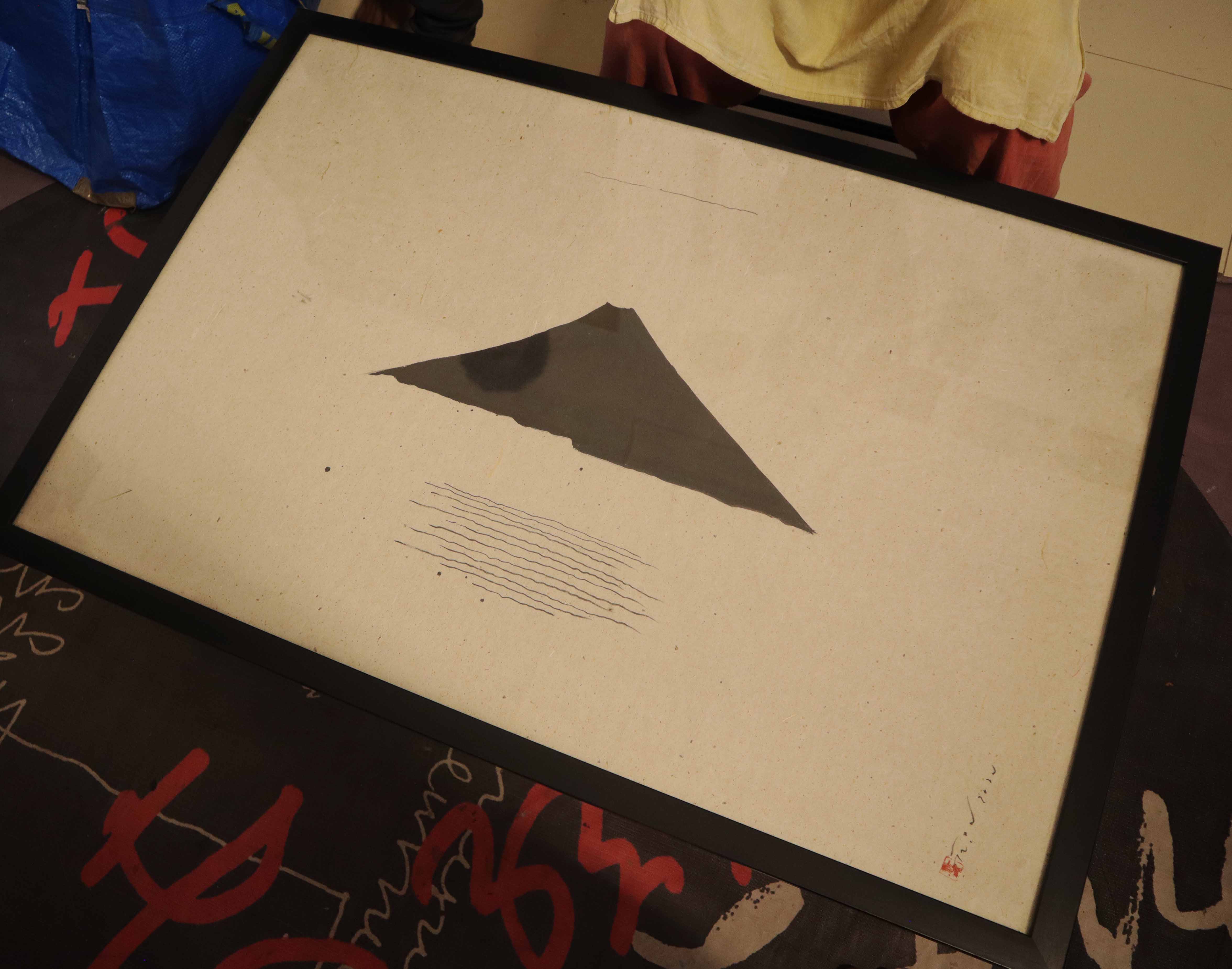

Hiran Mitra

Hiran Mitra

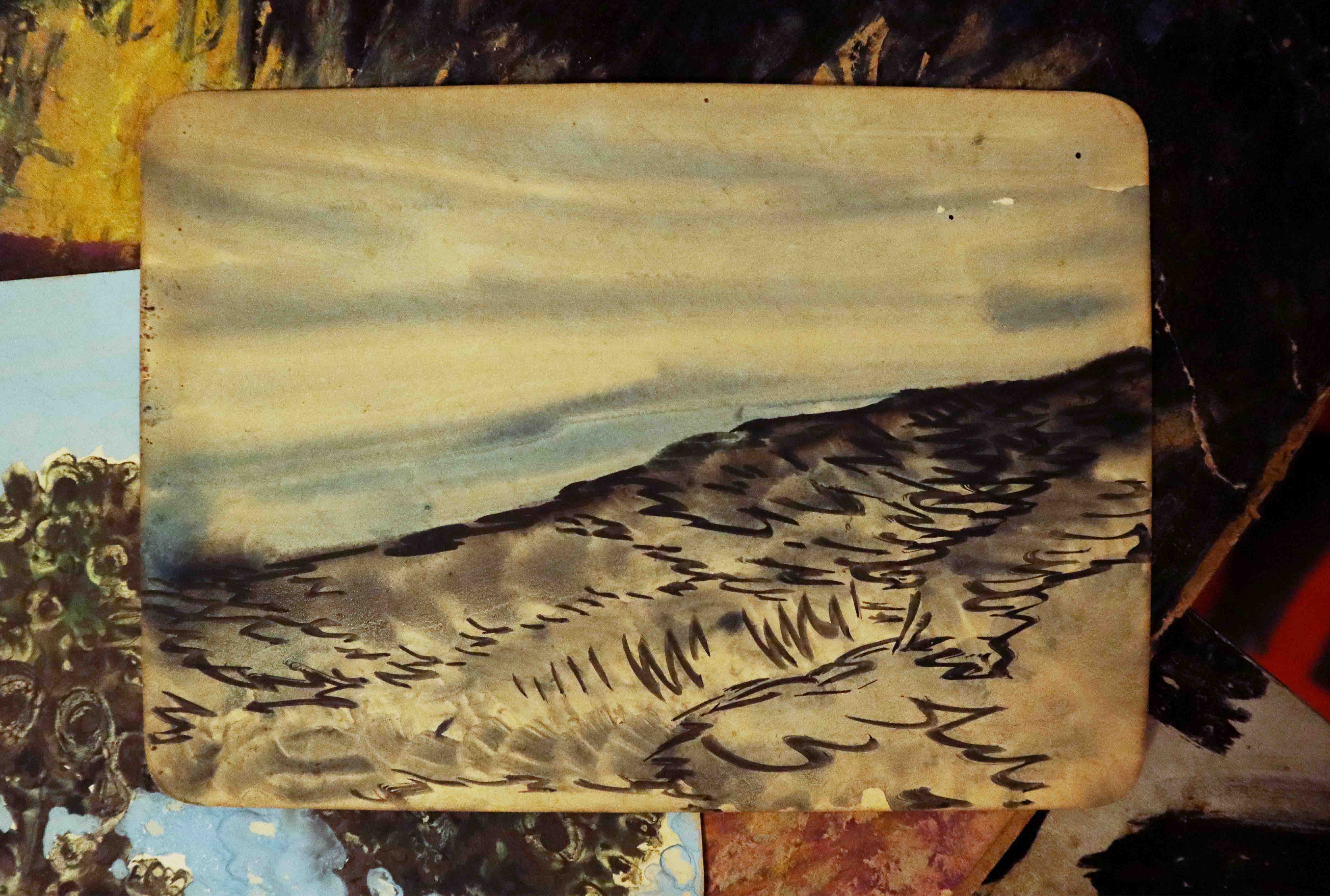

Gopal Ghose taught Hiran Mitra at the Government College of Art and Craft, Kolkata, that august institution for academic training in the arts undertaken by several generations of Indian artists since the late-nineteenth century; a site that is informed as much by formal training as experimental pedagogies championed by artists like Asit K. Haldar and Mukul Dey, among others, who were its Principals in their time. Mitra’s own landscapes can veer between formal, geometric abstractions and East Asian-influenced views of mountains. |

|

According to Mitra, Ghose would spend a lot of his time cycling around the Bengal countryside and painting natural scenes. His literary influences are invoked by Mitra in his frequent references to the poet Jibanananda Das, who wrote the famous poem ‘Banglar mukh ami dekhiyachi’ (I have seen the face of Bengal) and the novelist, Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay, who wrote the classic novel Pather Panchali (Song of the Road, later filmed by Satyajit Ray as his debut film), and Aranyak (The Forest). Mitra quotes from Aranyak in his own writings to suggest the many ways in which his writing slips into image-making and image-making finds its way into language, each enriching and even estranging the other from familiar and normative worlds of sense or sensibility. ‘His (Bibhutibhushan’s) language is suffused with colour. In our water colours, Gopal Ghose would inaugurate festivals of colour where many such unknown species of flowers would crowd the canvas. The emotional image-force that Bibhutibhushan employs to enthrall his readers is the same force that Gopal Ghose employs to depict his images drawn from his wild peregrinations.’ Hiran Mitra, Image-thinking and image-relations in language. |

|

|

|

This feeling for nature is traced through the writings of Benode Behari Mukherjee too, as Mitra quotes from the latter’s texts to show how the artist battled darkness with senses of colour that is communicated to him by touching well-known flowers. In Mukherjee’s works we see a similar sense of transformation where human bodies appear to grow into natural forms and vice versa. |

|

|

|

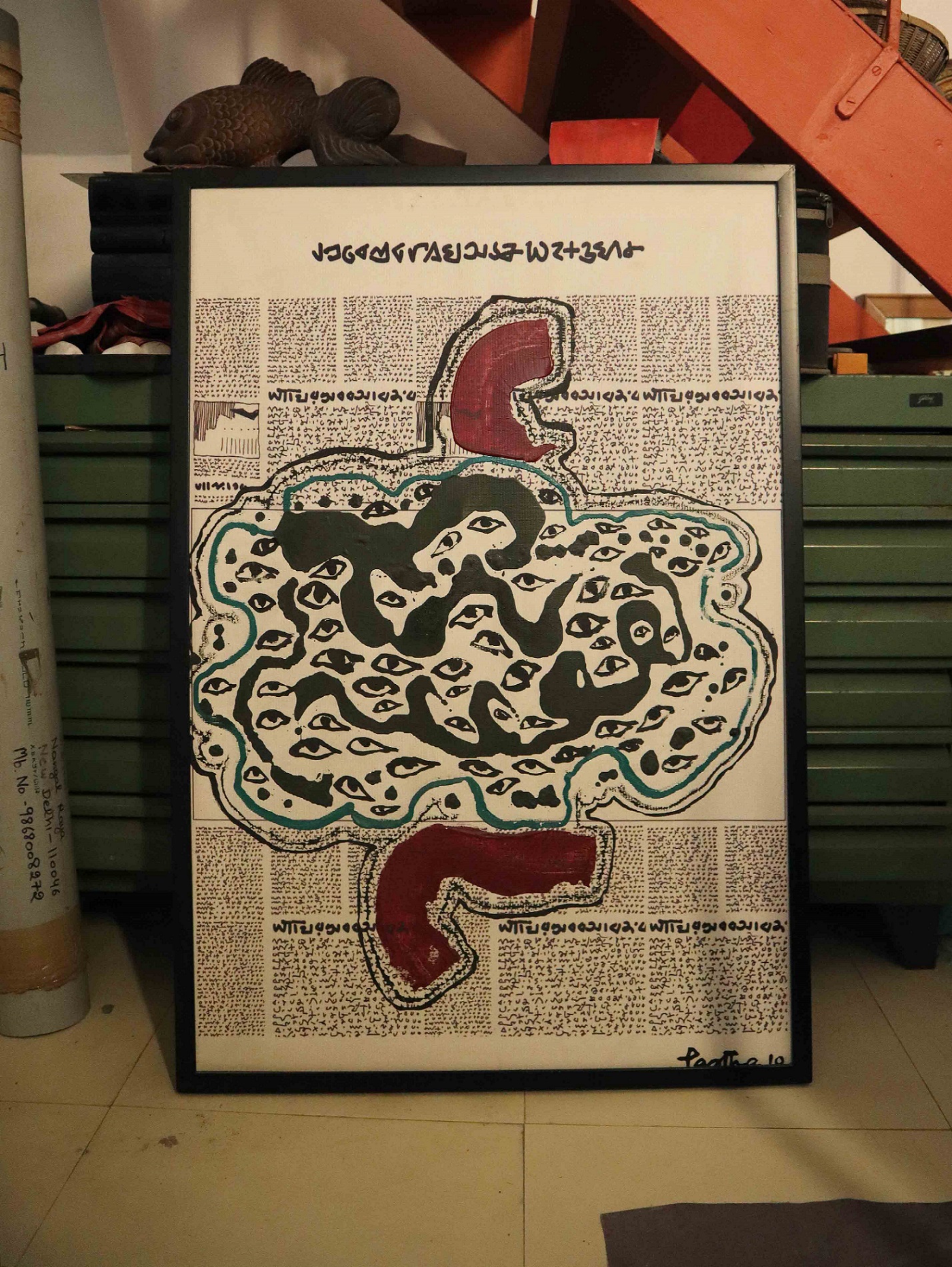

A frequent collaborator and friend of Mitra’s is Partha Pratim Deb, some of whose paintings, collages and sculptures were in Mitra’s collection as well. They worked together on an exhibition titled The Art of Advertising that sought to critique the rise of marketing as a strategy to sell artistic work. They also used the occasion to point out the artificial hierarchies imposed in art schools, especially when it came to design or illustration work, which was usually seen as ‘inferior’ to classical painting or sculpture. |

|

Detail from a work by Partha Pratim Deb |

Partha Pratim Deb

Partha Pratim Deb

Partha Pratim Deb

Hiran Mitra

Aside from scluptures using found materials and objects, Deb had also made some Taalpatar shepai (Palm-leaf soldier), a traditional craft object made out of palm leaves and bamboo sticks with strings attached. Mitra has also worked with found objects and collage, using organic materials like driftwood. It references the work of the great Bengal modernist Abanindranath Tagore who made his own series of wooden sculptures/ toys that he fondly named katum kutum, a playful phrase suggesting the rough framework of a crafted object. |

|

Hiran Mitra met Meera Mukherjee in the 1960s. Once again, he was recording his impressions of a documentary film that was being made on the famous sculptor when she was at work in a village called Elachi. |

|

|

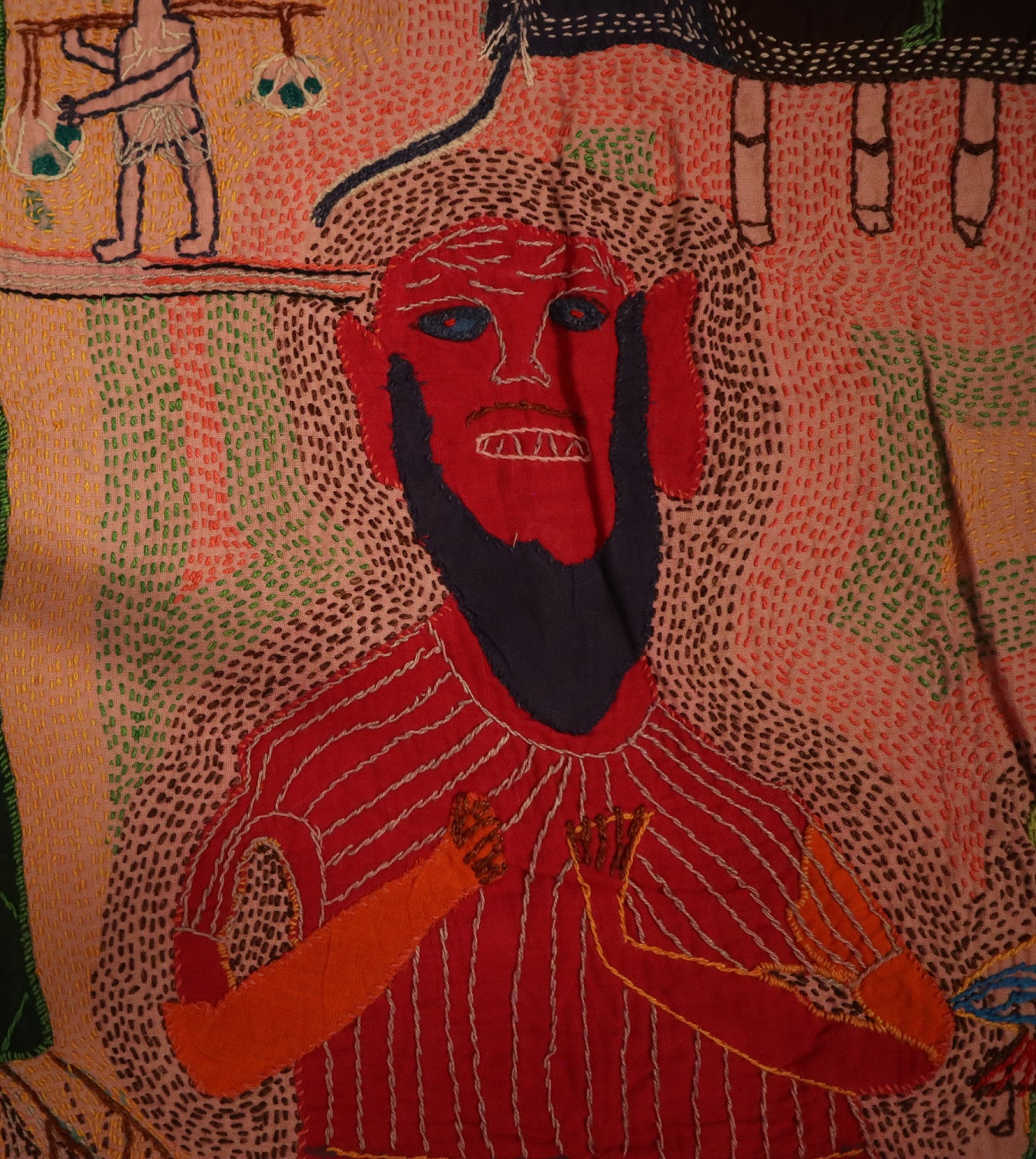

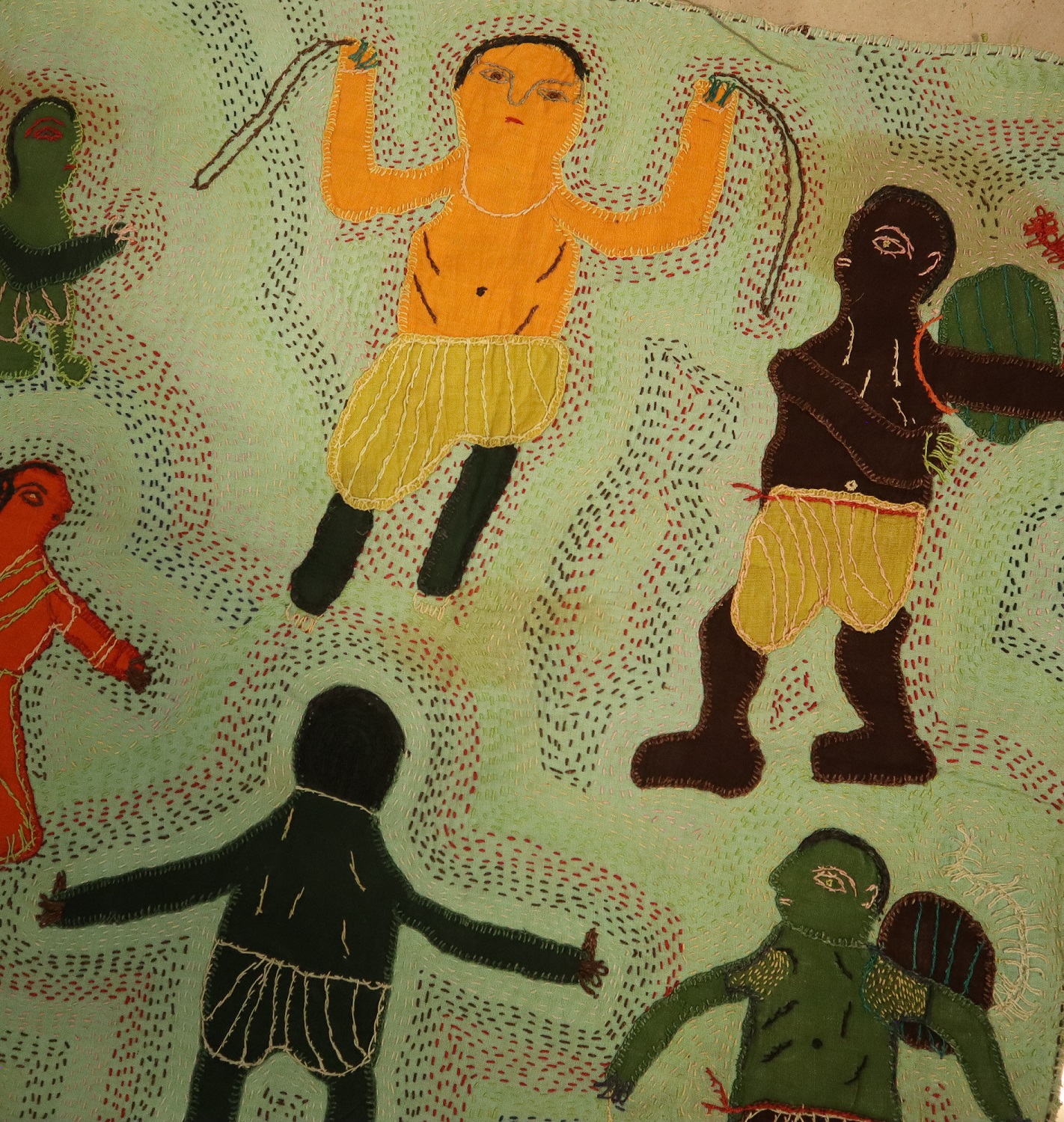

At the time, Mitra was associated with various film societies and movements across the city, constructing sculptural installations that were shown alongside screenings of films like The Battle of Algiers (1966). He observed Mukherjee at work in Elachi and made a set of drawings and collected a series of stitched kantha that was made under Mukherjee’s supervision. Mitra’s wife, Anita, has conducted several years’ research into kantha-making practices and has made some herself, which she generously showed us. |

|

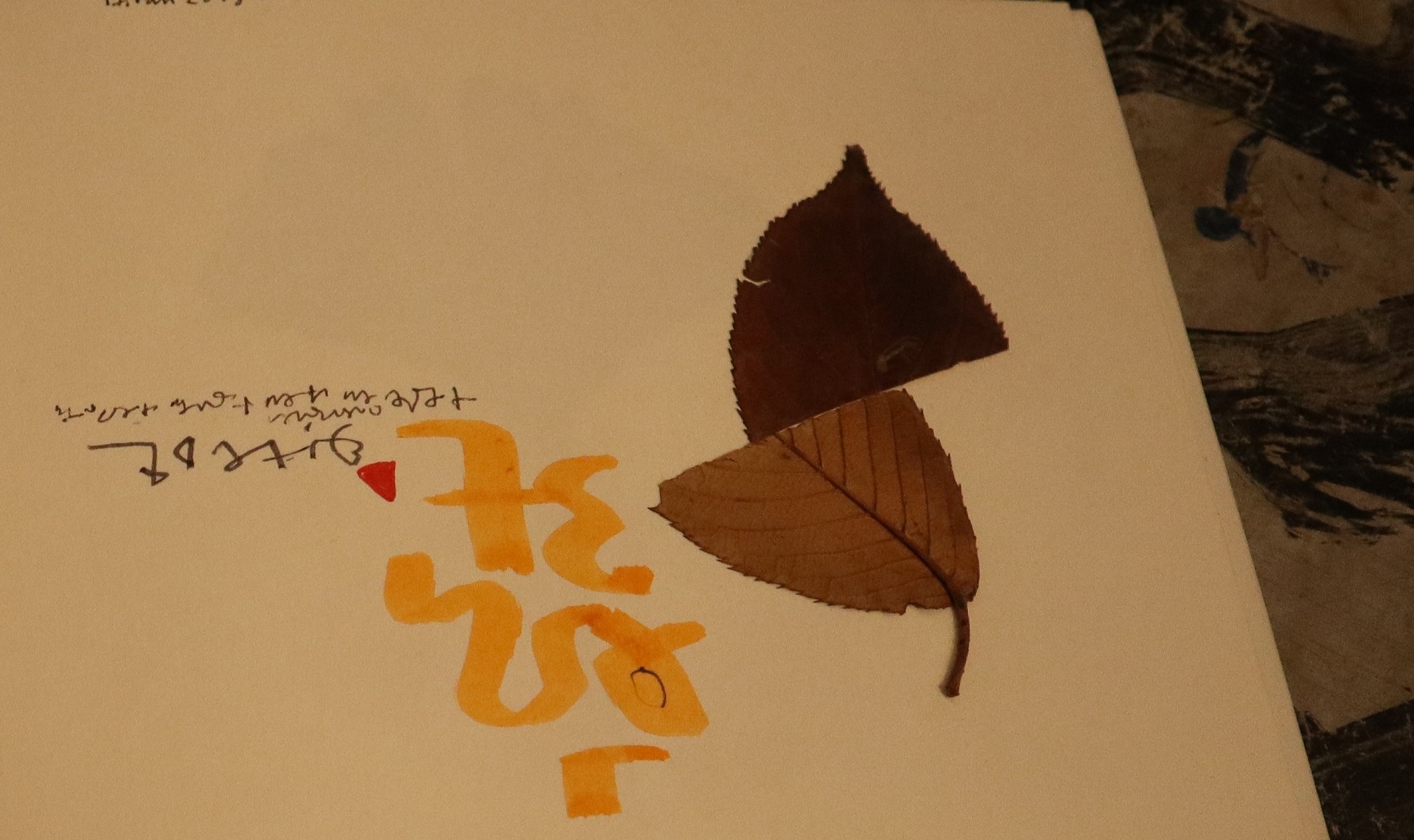

Mitra also made an elaborate scrollwork drawing from his influences in East Asian art and the impression of the natural environment where he made the work in situ. Aside from this, a new series of works offered a delicate treatment of leaves and organic matter that were impressed upon Japanese paper that he had been sent from a friend in that country. These offered a nice summation of his career, signalling the variety of influences he has absorbed in his work over a lifetime's worth of experimental practice and indicating a vision that seeks to push the modernist legacies of Bengal art beyond its familiar search for personal subjectivity into realms of risk-taking that is necessary in order confront the world of another, or perhaps an ‘Other’, that will present an aesthetic and cultural challenge to this complacent self-identity in a global world. |

|

|

|

|