Behind the Canvas: Verso as an archive

Behind the Canvas: Verso as an archive

Behind the Canvas: Verso as an archive

When you look at a painting, what you are usually admiring is its recto or the front, the side that holds the artist’s vision rendered in oil, acrylic or other mediums. But have you ever thought of turning a painting around and looking at the back? You might wonder, why would anyone do that? And to that, I say, why not?

A painting is a micro-universe, and its story isn’t confined to what you see on the front. The verso often holds signatures, notes, stamps, stickers, or labels; small but significant clues that help authenticate, date, and trace the provenance of a work. Together, they piece an artwork’s journey across collectors, galleries, and even continents. At DAG, we make it a point to study not just the recto but also the verso of each artwork. From the examples listed below we can look at some exciting discoveries, contextual histories, and even hidden stories of artworks from our collection.

|

George Keyt, Untitled (Seated Woman), Oil on canvas, 1946, 33.7 x 24.5 in. Collection: DAG |

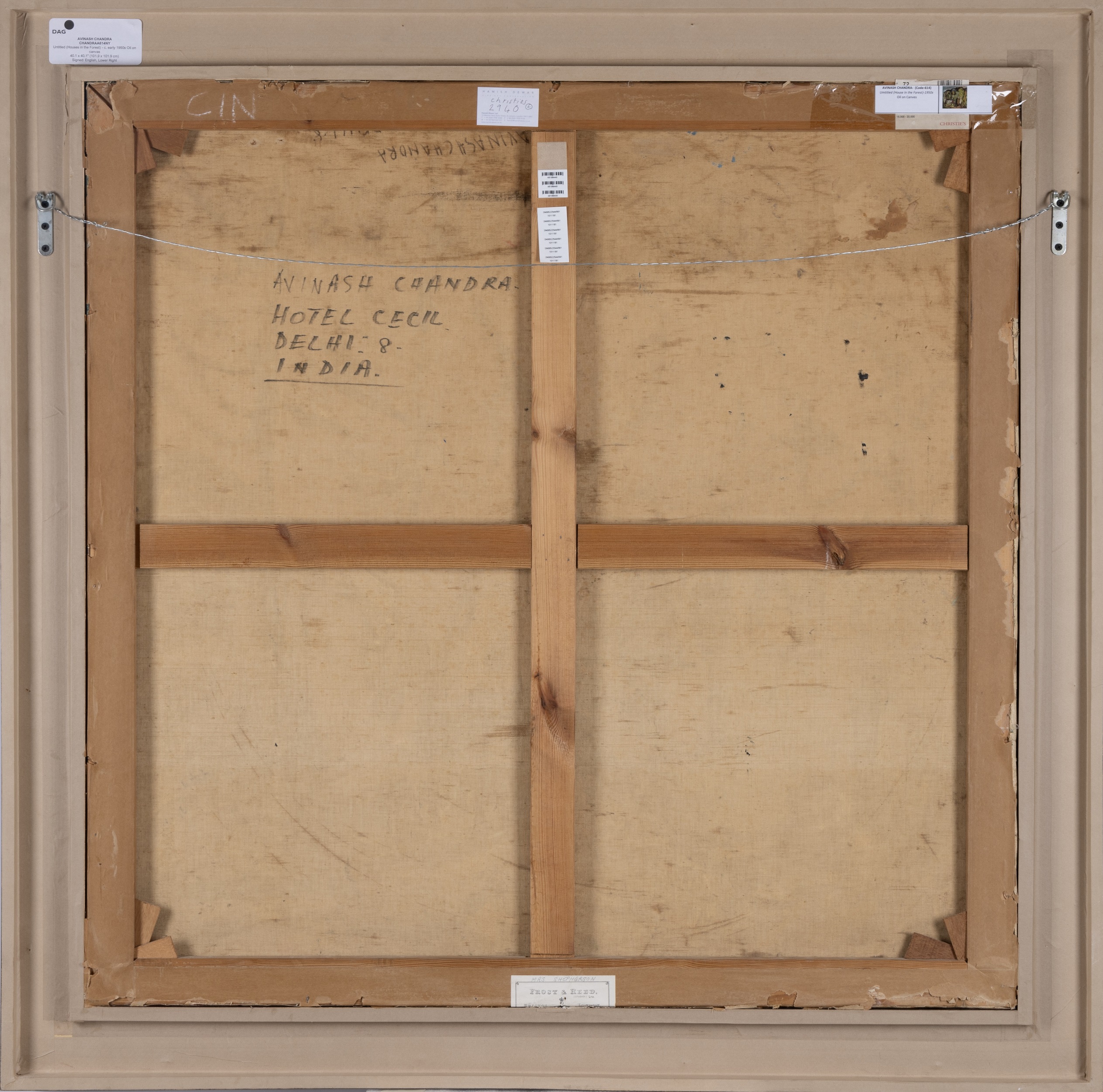

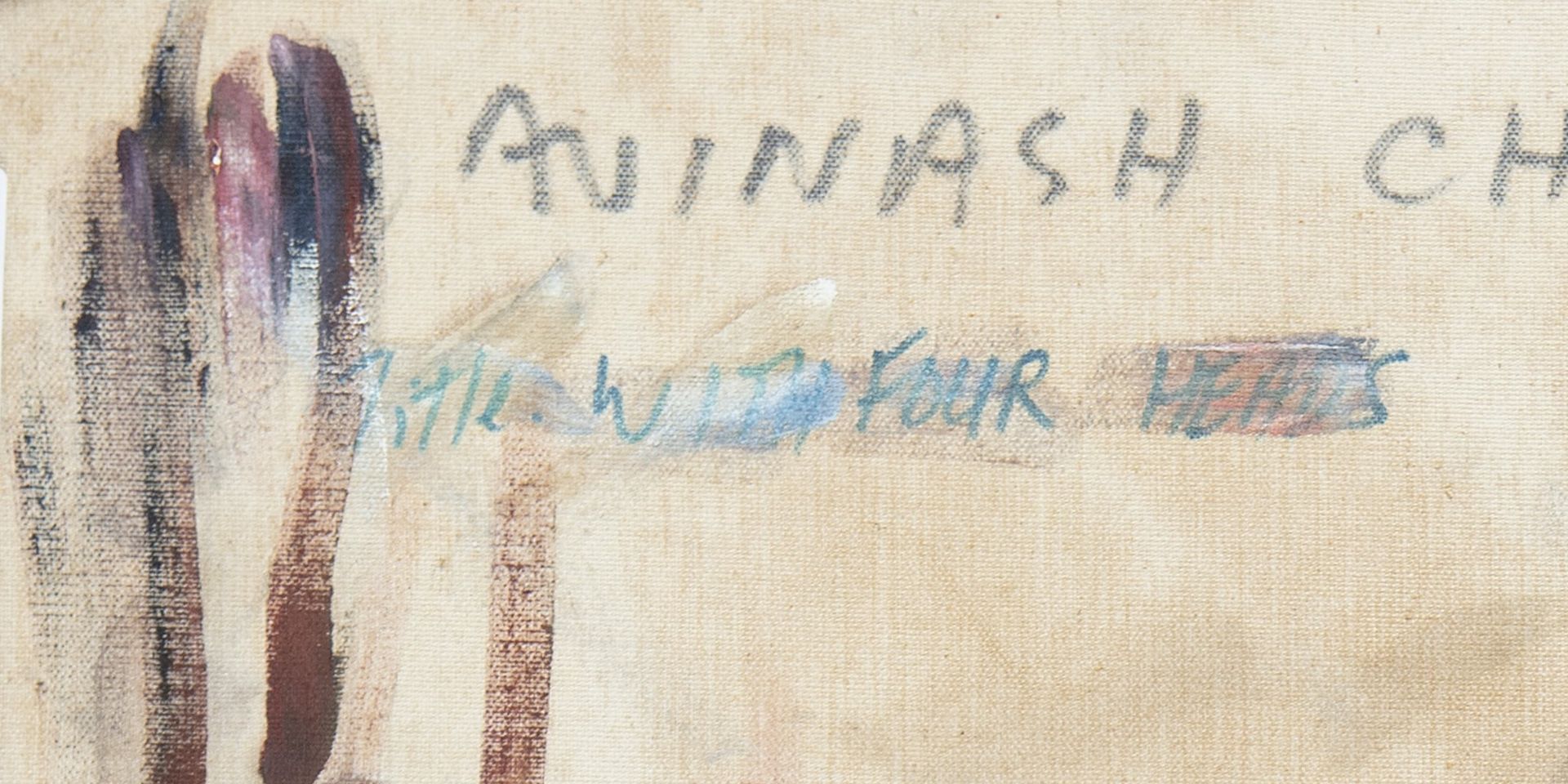

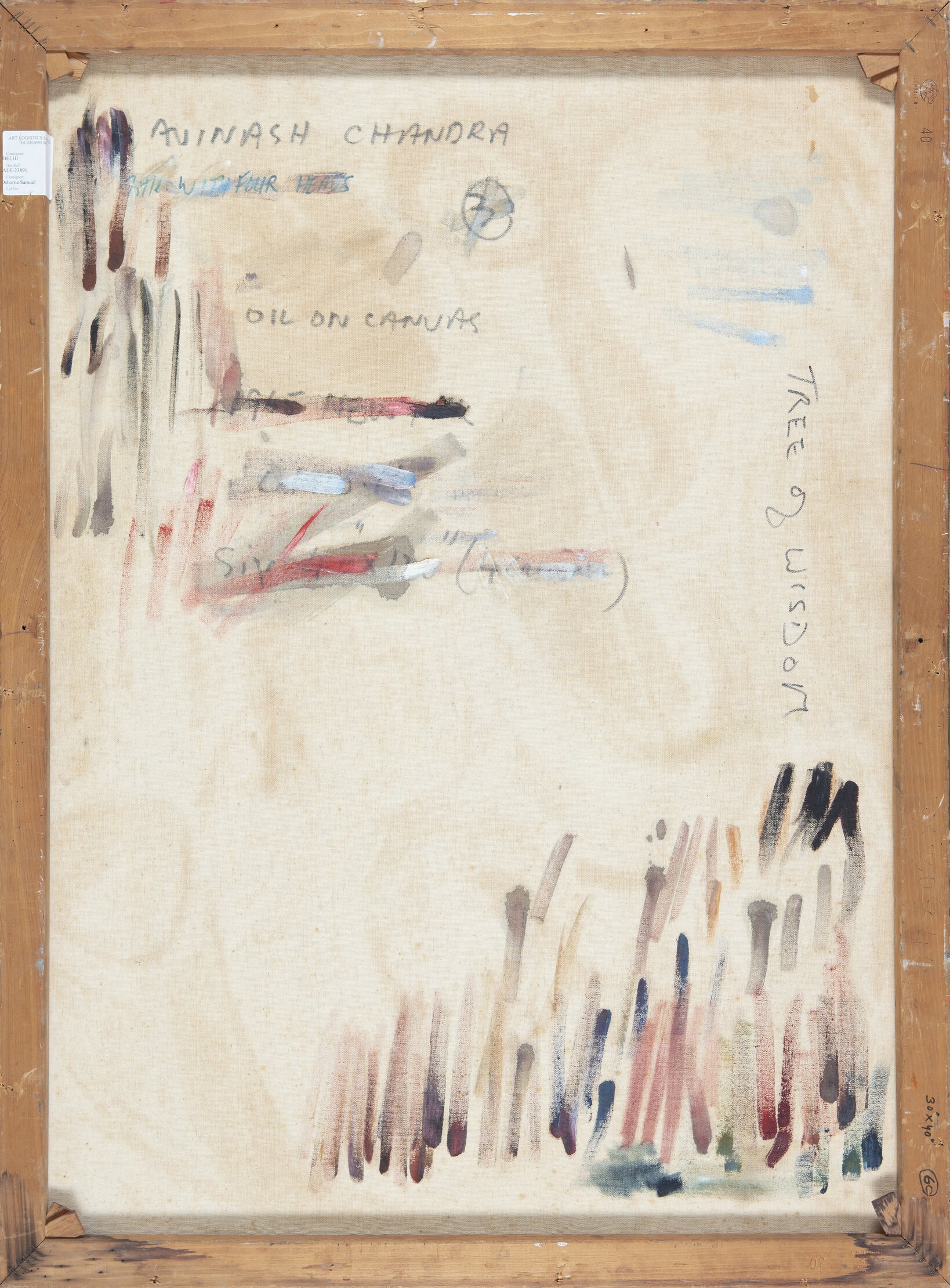

Artists often tell intricate stories through their paintings, yet sometimes, the real key to understanding these works lies on the reverse side. The backs of canvases or paper can reveal signatures, titles, dates, and even addresses. Occasionally, we uncover unusual and telling details. For instance, on the back of Avinash Chandra’s Tree of Wisdom, the original title With Four Heads is crossed out—hinting at a shift in his artistic direction. We also see swathes of paint, likely used to test his palette before committing to the final composition, a practice observed in several of his works.

Avinash Chandra, Tree of Wisdom, Oil on canvas, 1987, 30.0 x 40.0 in. Collection: DAG

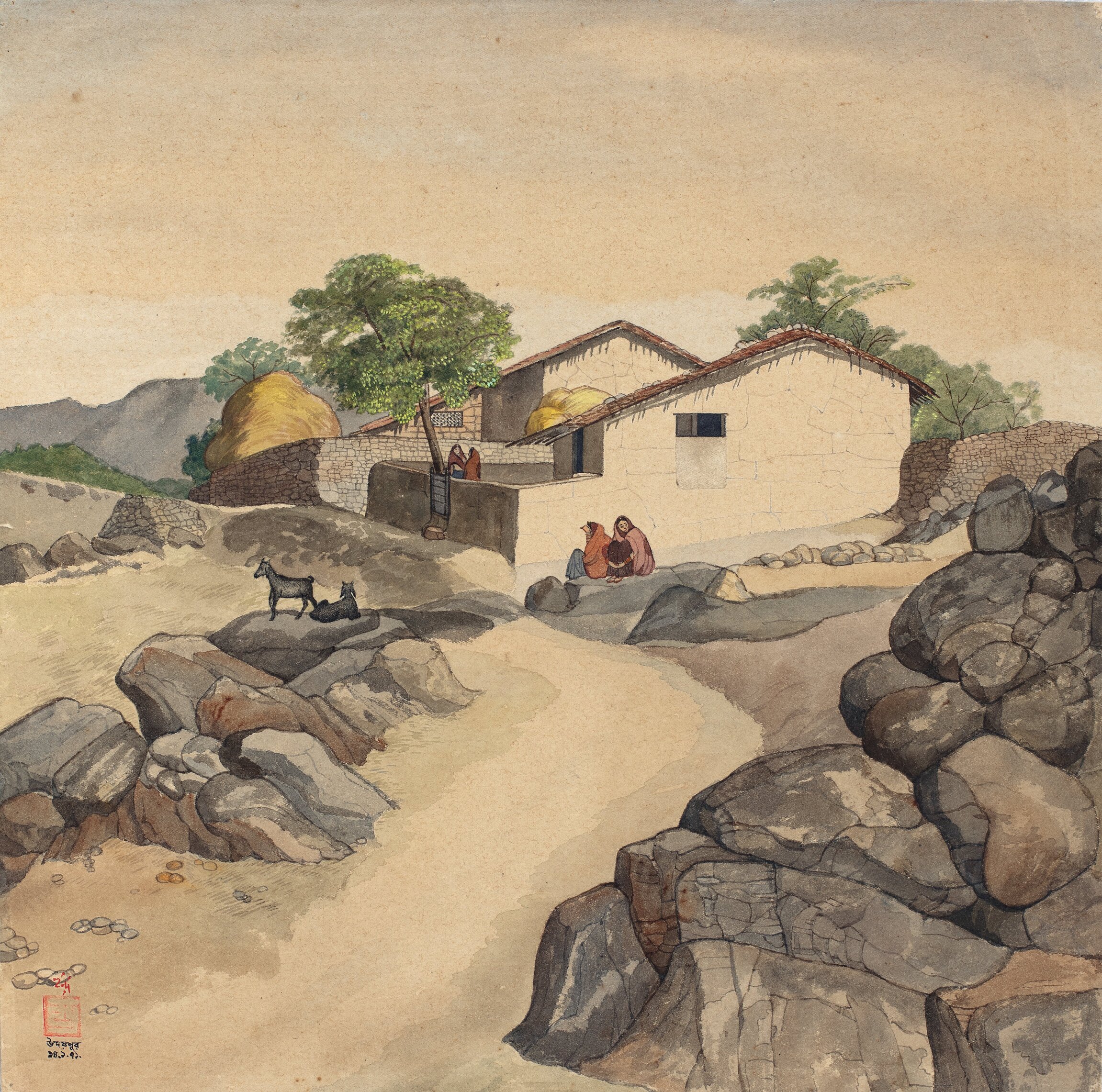

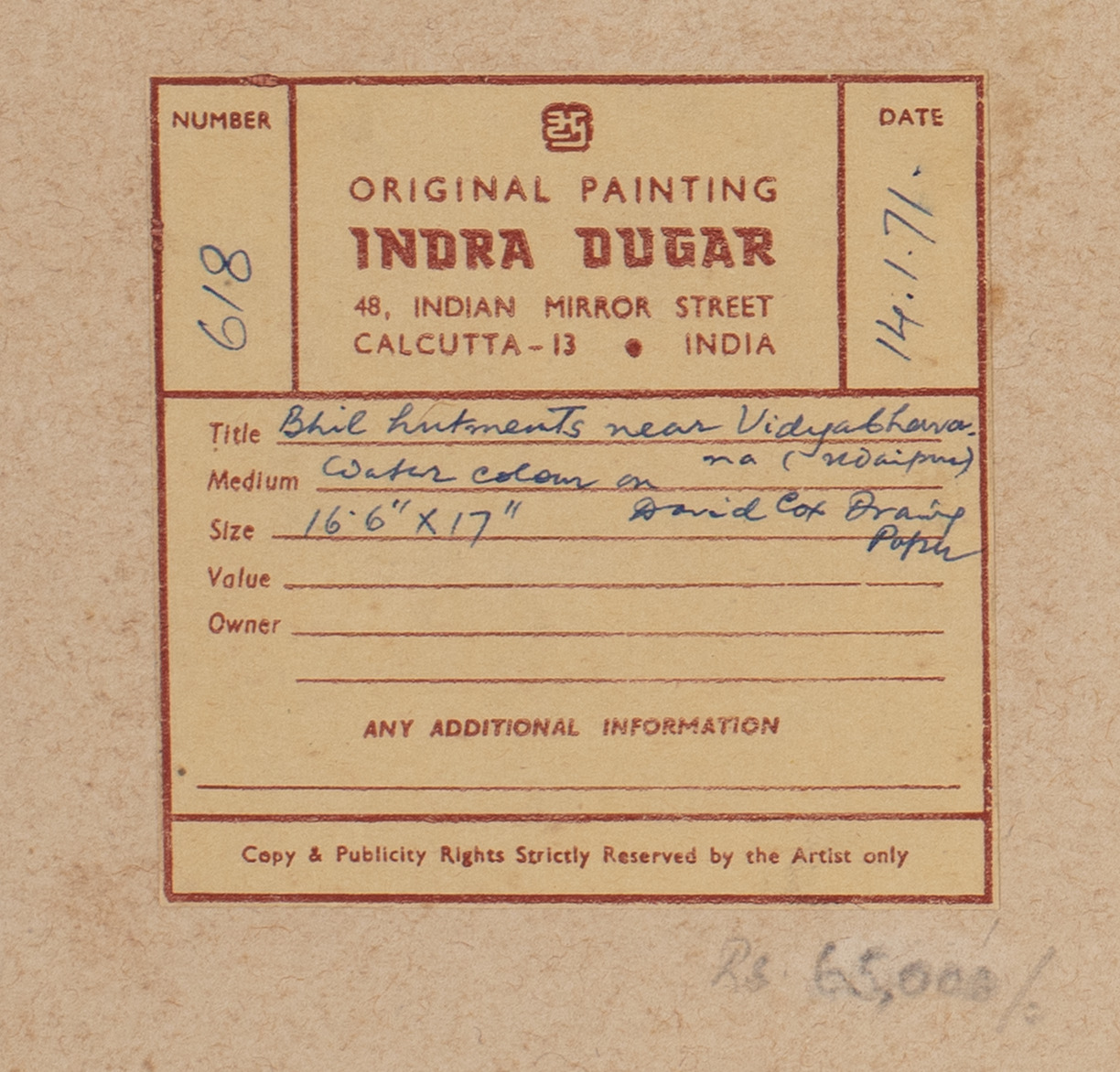

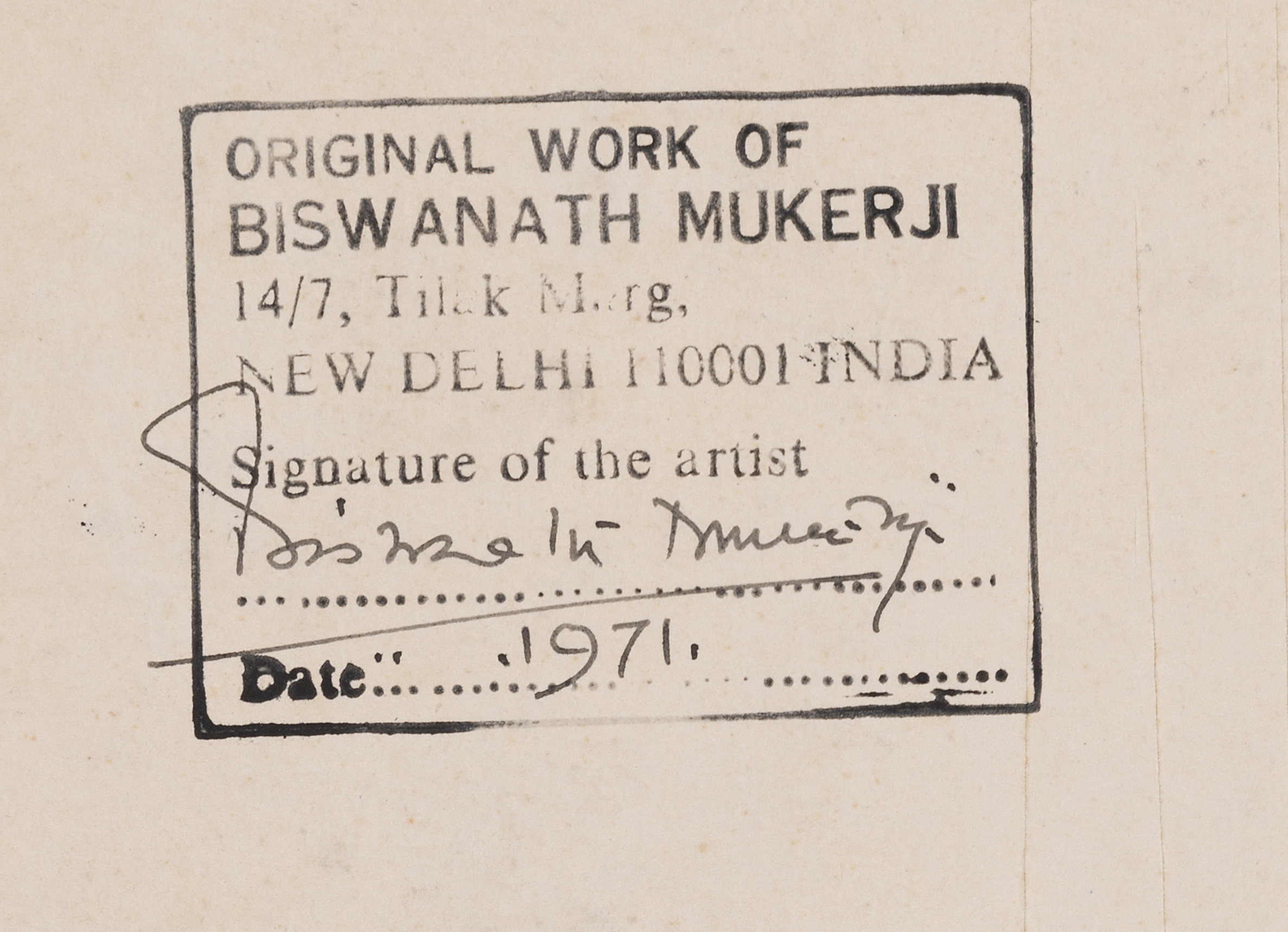

Another interesting detail that some artists provide are their personalised stamps or labels. We have in our collection two famed modernist artists , Indra Dugar and Biswanath Mukerji. Both these artists have uniquely distinct styles, yet the one thing they have in common is they both mark their works, one with a label and the other with a stamp. Indra Dugar adds a personal label that provides details of his works such as the title that helps identify the landscape he has painted, as well as the year and even the material he used. As for Mukerji, he stamps his work and signs it as well, thus authenticating the work as truly his.

|

Indra Dugar, Bhil Hutments near Vidyabhavana (Udaipur), Watercolour on paper, 1971, 16.5 x 17.0 in. Collection: DAG |

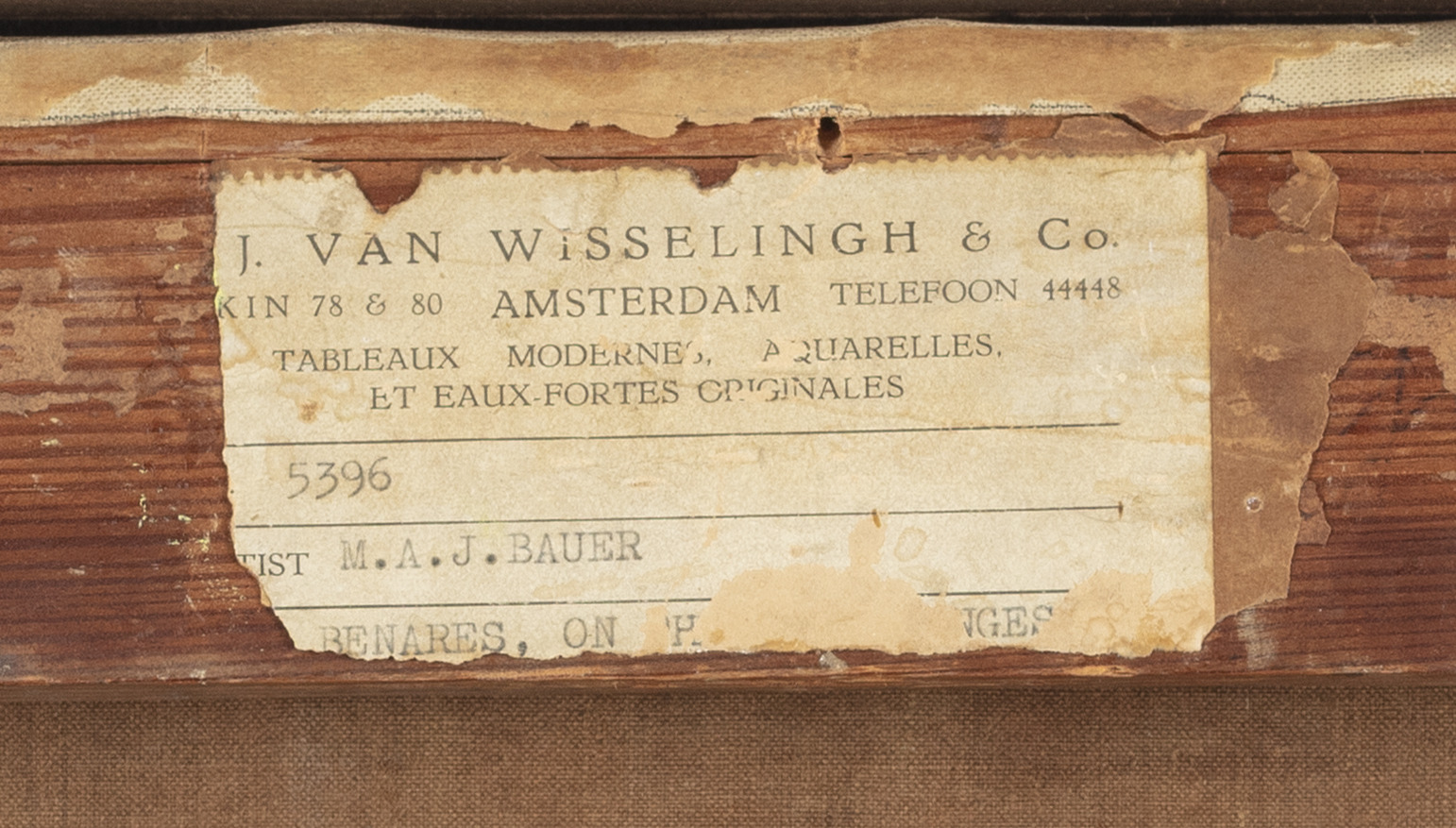

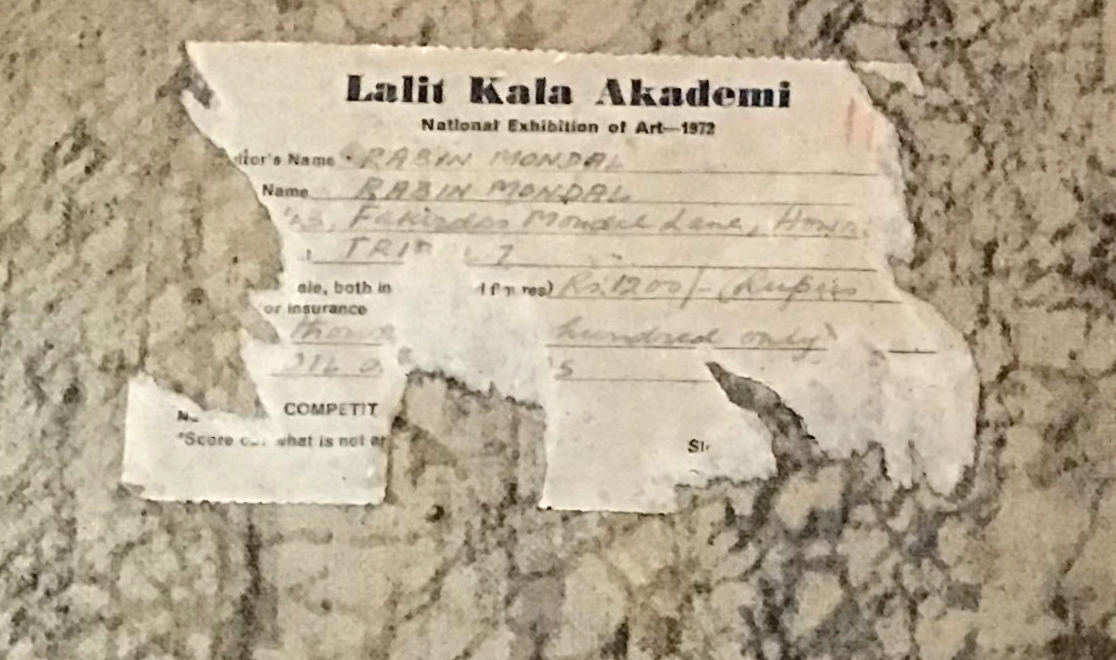

Very often works are sold at auction houses or through various art galleries whether they be in India or anywhere around the world. Each time a work is sold or exhibited at either platform, the works are marked at the back with a label, sticker or a stamp. These act as passports for the works and help provide an idea of how well-travelled a work might be, where it was earlier housed, and who collected it. Some labels provide information that is not even mentioned on them. For example, we have in our collection numerous works by the celebrated Dutch artist, Marius Bauer who travelled extensively.

Marius Bauer, Benares, Oil on canvas, 16.0 x 21.0 in. Collection: DAG

Many of his works bear a label on the back by E. J. van Wisselingh, an Amsterdam-based art dealing company established in 1838. This company not only supported Bauer’s travel but also provided him with the materials he needed to create his art. These labels are important as they not only help identify the titles of the works but also verify their authenticity. As we see in this picturesque work, the landscape could have been from anywhere in South Asia, but the title from the label helps us know that this is a Ghat of Benares. Without Wisselingh’s patronage, we may have never witnessed the magnificent works created by Bauer.

Many of our works have been sourced through auction houses as we see ample stickers, labels and barcodes on the back. Some of the most popular ones are Christie’s, Sotheby’s and Bonhams’. These stickers are very valuable as they not just mention the details of the artwork but also provide the provenance history. For example, this work by George Keyt has a Christie’s sticker on the verso. From this we know exactly which sale it was in and thus trace the provenance history of the work. This work by Keyt, in which we see the cubistic language strongly evolved here, was a part of the Collection of Professor C. C. de Silva, who was a pioneering Sri Lankan paediatrician. And from his collection, it came to DAG via Christie’s.

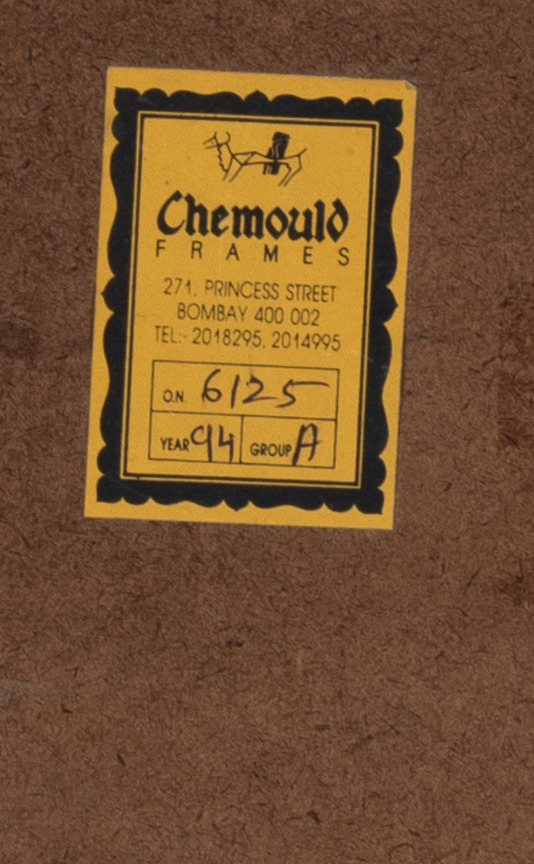

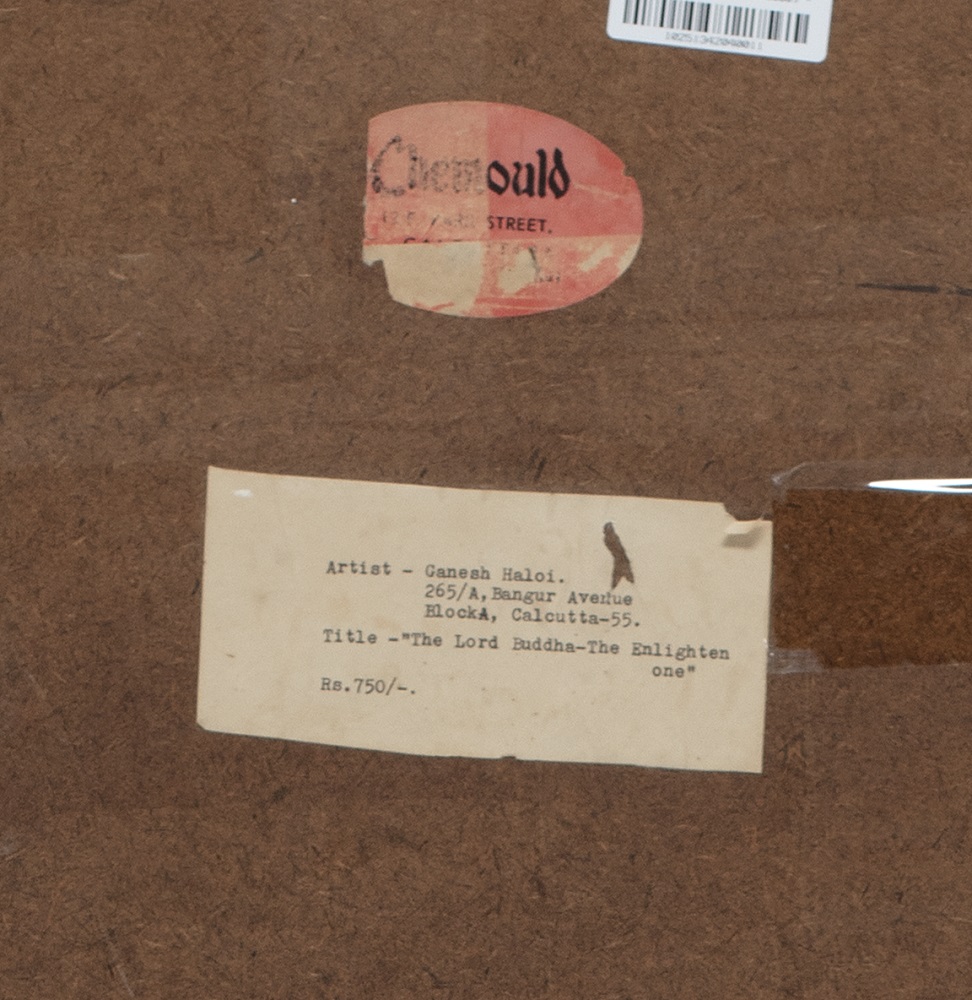

Framer labels may seem unremarkable, but they often reveal enduring artist and framer relationships. Framer labels or stickers often provide us with not only an artwork’s story but also the story of the frame maker itself. Chemould, a name now synonymous with a contemporary art gallery, had its humble beginning in the 1940s as a modest framing shop on Princess Street, Mumbai. Owned by Kekoo Gandhy, it became a favourite of the Bombay Progressives, including M. F. Husain, S. H. Raza and F. N. Souza, who would get their works framed there. Gandhy supported these artists even before they became well-known, by hanging their paintings in his framing shop and eventually launching the Chemould Gallery in 1963.

M. F. Husain, Untitled, Serigraph on paper, 19.5 x 26.0 in. Collection: DAG

They went on to open two more stores, one in Kolkata and one in Delhi. This work by Ganesh Haloi has the Chemould Frames sticker with the Kolkata address of Park Street.

|

Ganesh Haloi, The Lord Buddha - The Enlightene d One, Oil on canvas, 46.2 x 34.5 in. Collection: DAG |

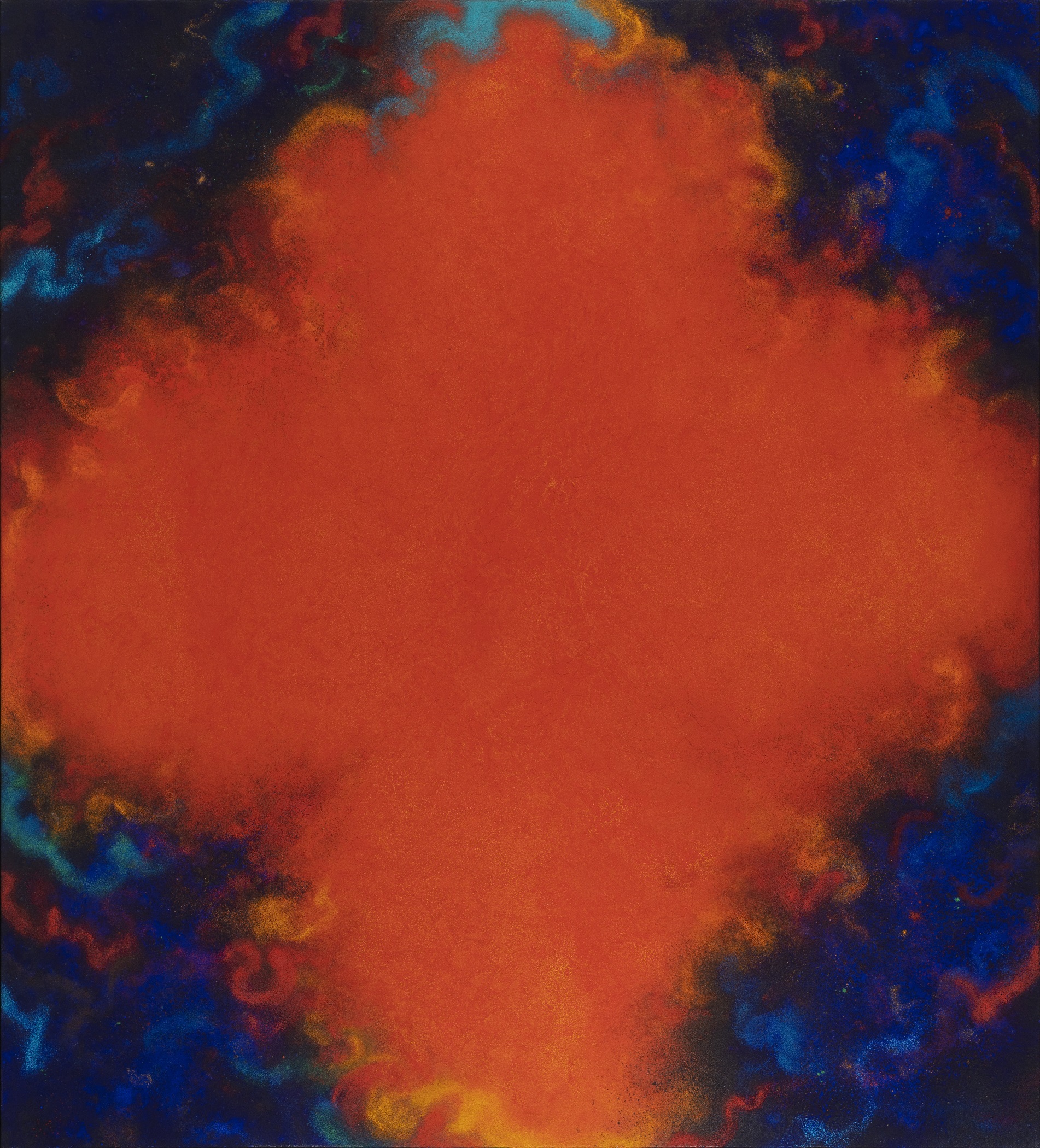

Another notable stamp found on the reverse of some works by a significant artist represented by DAG is that of the ACP Viviane Erhli Galerie, seen on pieces by Natvar Bhavsar. Based in Zurich, Switzerland, the Erhli Galerie focused primarily on contemporary art, with Bhavsar as one of its most prominently featured artists. The gallery often used oak or pine for its frames—woods commonly found in Switzerland—recognisable by their distinct hues. Although the gallery has since closed permanently, Bhavsar’s works now stand as lasting mementos of its legacy.

|

Natvar Bhavsar, Vasoo, Dry pigments with oil and acrylic mediums on canvas, 1997, 61.0 x 55.0 in. Collection: DAG |

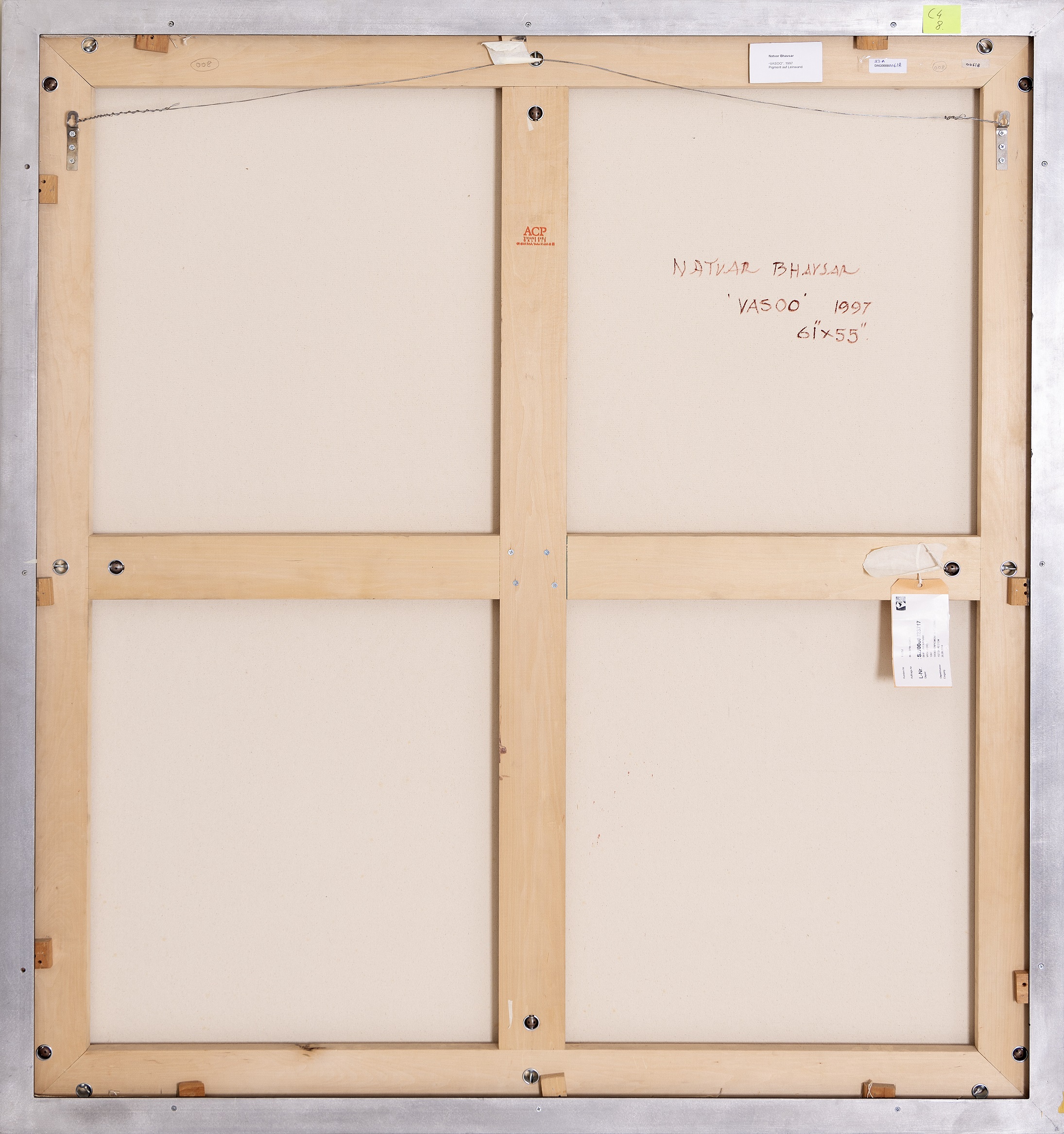

Artworks often travel more than we do, and we know this from the various exhibition labels that we see on the back. Some of the popular exhibitions in India were organised by the Lalit Kala Akademi (L. K. A.) which was established in 1954 to promote modern Indian art as part of a larger national cultural identity. For instance, we have a work by Rabin Mondal with an L. K. A. label from 1972. These labels often help us date artworks, like in this case as the artist has not provided the date, but the label has the year 1972. So clearly this work was made around then or even earlier.

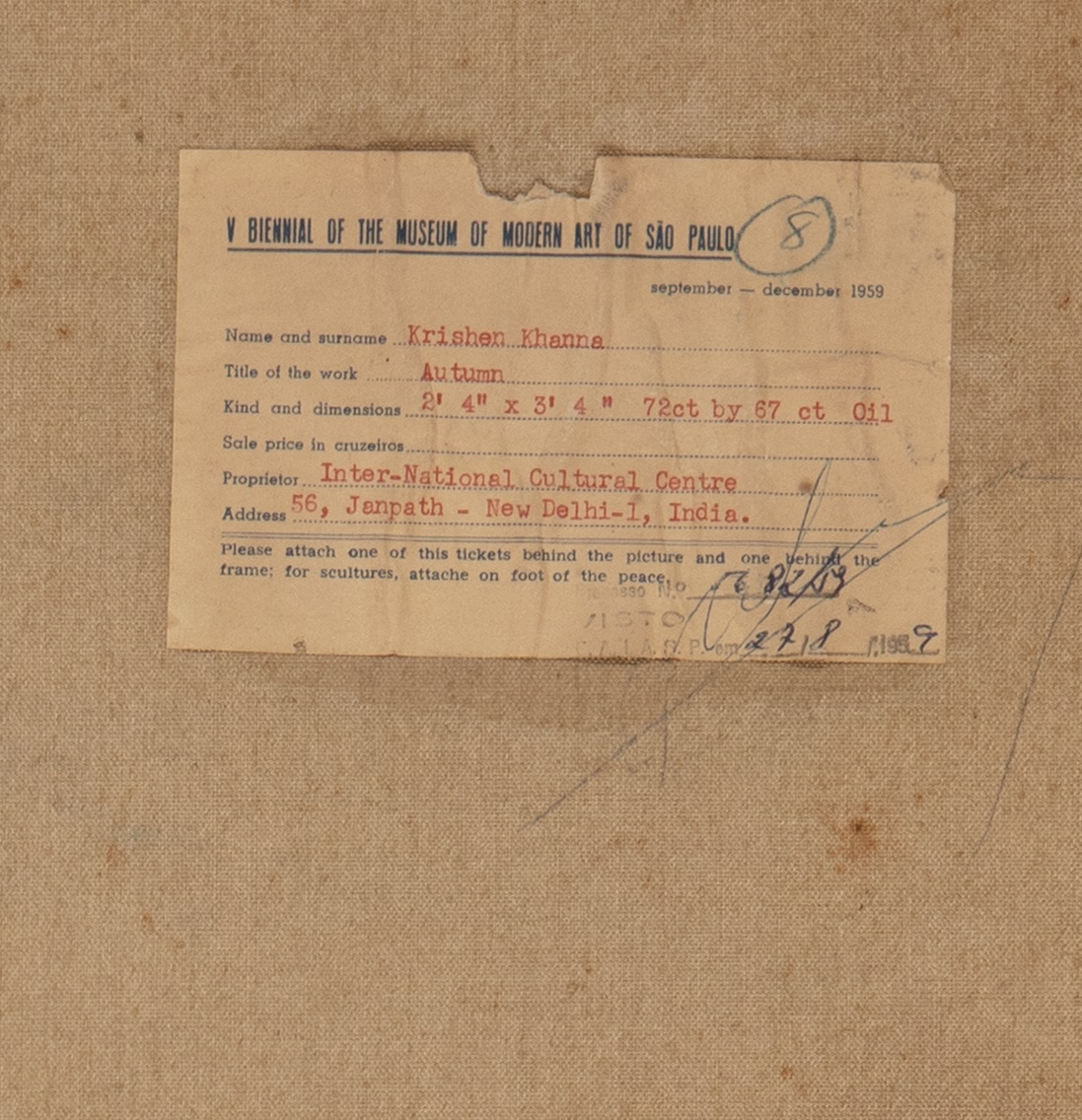

Art Biennales are grand, international exhibitions, and having one's work featured in them is a significant achievement. The Venice Biennale, begun in 1895, is one of the oldest, but many others have followed worldwide. At DAG, we have artworks whose verso labels confirm their selection in prestigious events like the São Paulo Biennale. One such work by Krishen Khanna was selected for the 5th São Paulo Biennale in 1959; an edition that featured 689 artists from 47 countries.

|

Krishen Khanna, Autumn, Oil on canvas, 1959, 39.5 x 29.0 in. Collection: DAG |

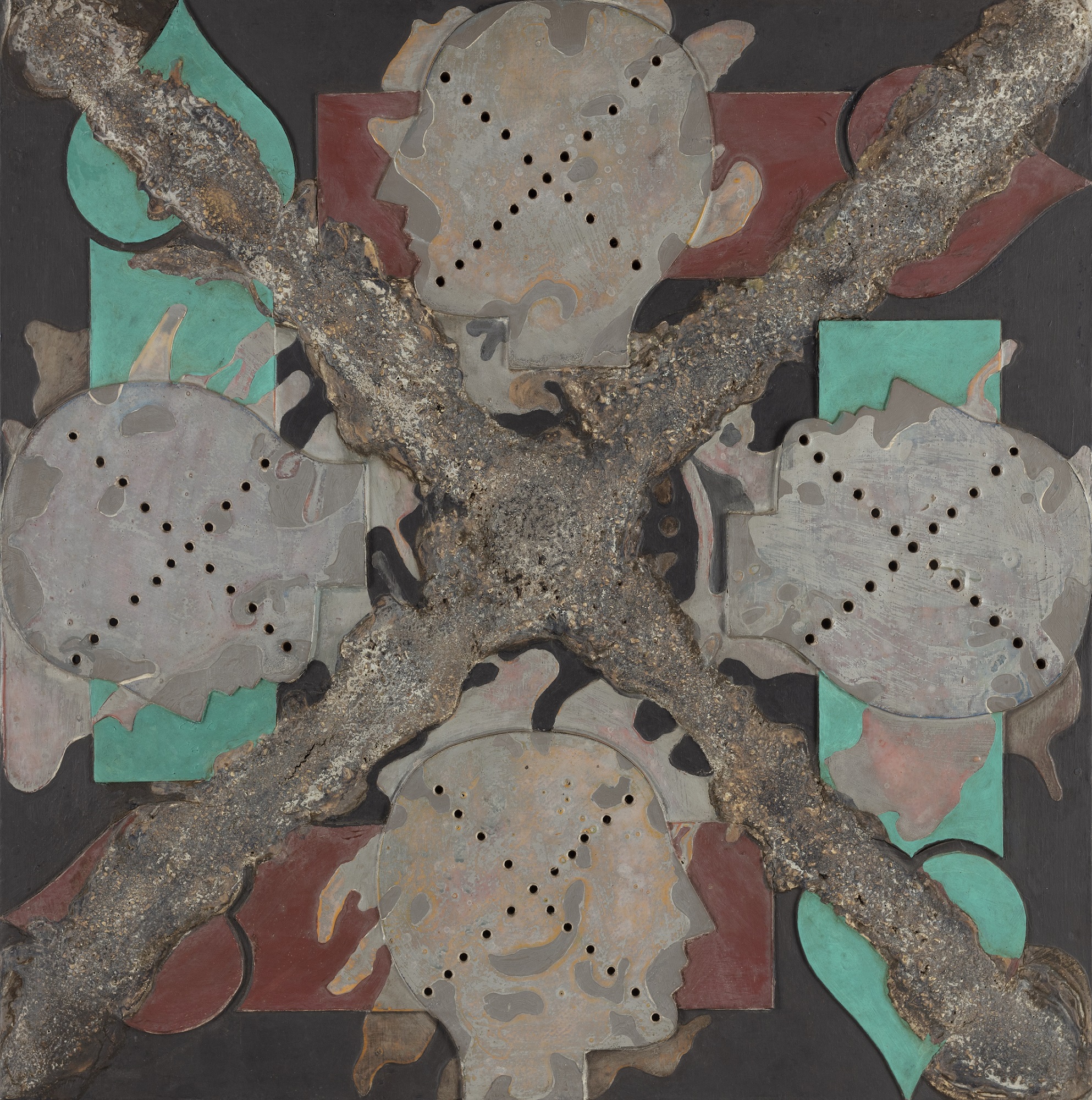

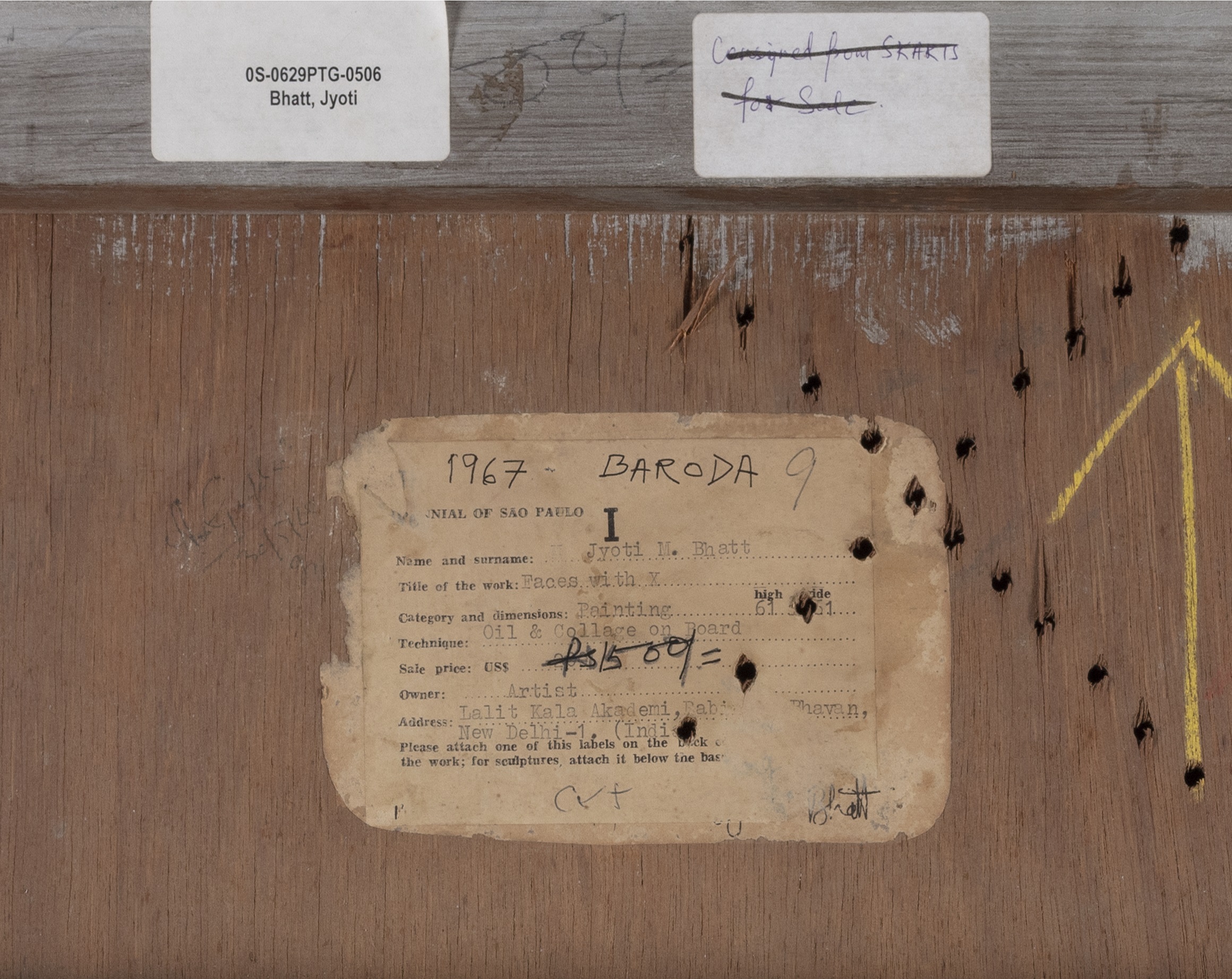

Another artist, Jyoti Bhatt, participated in the 9th edition in 1967. These labels are vital records of the artists' global recognition and participation in critical art movements of their time.

|

Jyoti Bhatt, Faces with X, Oil and mixed media on plywood, 1967, 24.0 x 24.0 in. Collection: DAG |

Artworks acquired by discerning collectors are often considered highly valuable when they re-enter the art market. One way to trace a painting's provenance is by examining the labels on its reverse. Collectors frequently create personalised labels that detail not only the artwork’s title and origin but also where it was purchased and even where it was displayed in their homes. Such information is invaluable in assessing an artwork’s historical as well as market value.

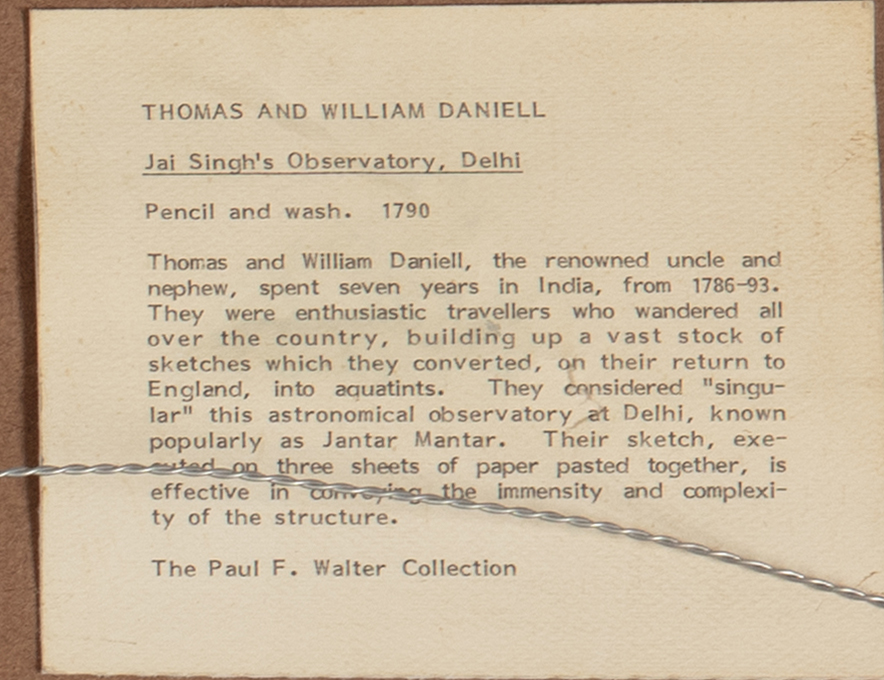

In our collection, we have a remarkable painting of Delhi’s Jantar Mantar by the celebrated British uncle-nephew duo, Thomas and William Daniell. On the back of the work is a prominent label indicating that it was once part of the esteemed Paul F. Walter collection. Walter was a passionate art connoisseur who held key leadership roles at both New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. His interests included a deep fascination with India, as seen in his collection of Indian travel posters and photographs by Linnaeus Tripe.

Thomas and William Daniell, Jai Singh's Observatory, Delhi, Watercolour and graphite on paper pasted on paper, 1790, 20.5 x 44.0 in. Collection: DAG

This label not only led us to the auction house through which the work was sold but also revealed where Walter had originally acquired it. Notably, many pieces from his collection fetched more than double their high estimates at auction—a testament to the exceptional value that artworks from well-documented private collections can command.

The verso of a painting is more than just the back of a canvas; it is a living archive. From determining the direction of an artists’ thoughts during the work’s making, and gallery journeys to exhibition records and collector histories, every stamp, sticker, or scribble enriches our understanding of the artwork. These modest bits of paper serve as a valuable bridge between the artwork and its ever-evolving context. To look only at the front is to see half the story; to turn it around is to uncover the layered histories that make the work of art a material object that occupies space in the world, even as it travels across it. So next time you encounter a painting, don’t forget to turn it around. The back might just tell you a story the front cannot.