|

From the Archives Banking on Colour: Reading R. K. Laxman's cartoonsUpasana Das June 01, 2023 R. K. Laxman is a familiar name to many of us through our encounters with his cartoons in our school curriculum or seeing his illustrations for his brother R. K. Narayan’s popular book, Malgudi Days. Laxman created his first caricature when he drew a humorous likeness of his father on the floor of his house. His mother was delighted and allowed it to remain on the floor for everyone to see. In school, after sketching a tiger which bore the likeness of his teacher, Laxman was reprimanded by him, until he convinced his teacher that it was merely an unlikely correlation. This was the beginning of Laxman’s involvement with caricature and convincing the ones he was caricaturing about the validity of his cartoons—in the future, he would convince Indira Gandhi during her time as a Prime Minister, that he should be free to draw his cartoons, no matter how critically they portrayed her political actions. |

R. K. Laxman's family photograph, 1925-26. The cartoonist, aged four, is seated on his mother's lap, while his brother, the future novelist R. K. Narayan, is standing at the back (centre).

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

|

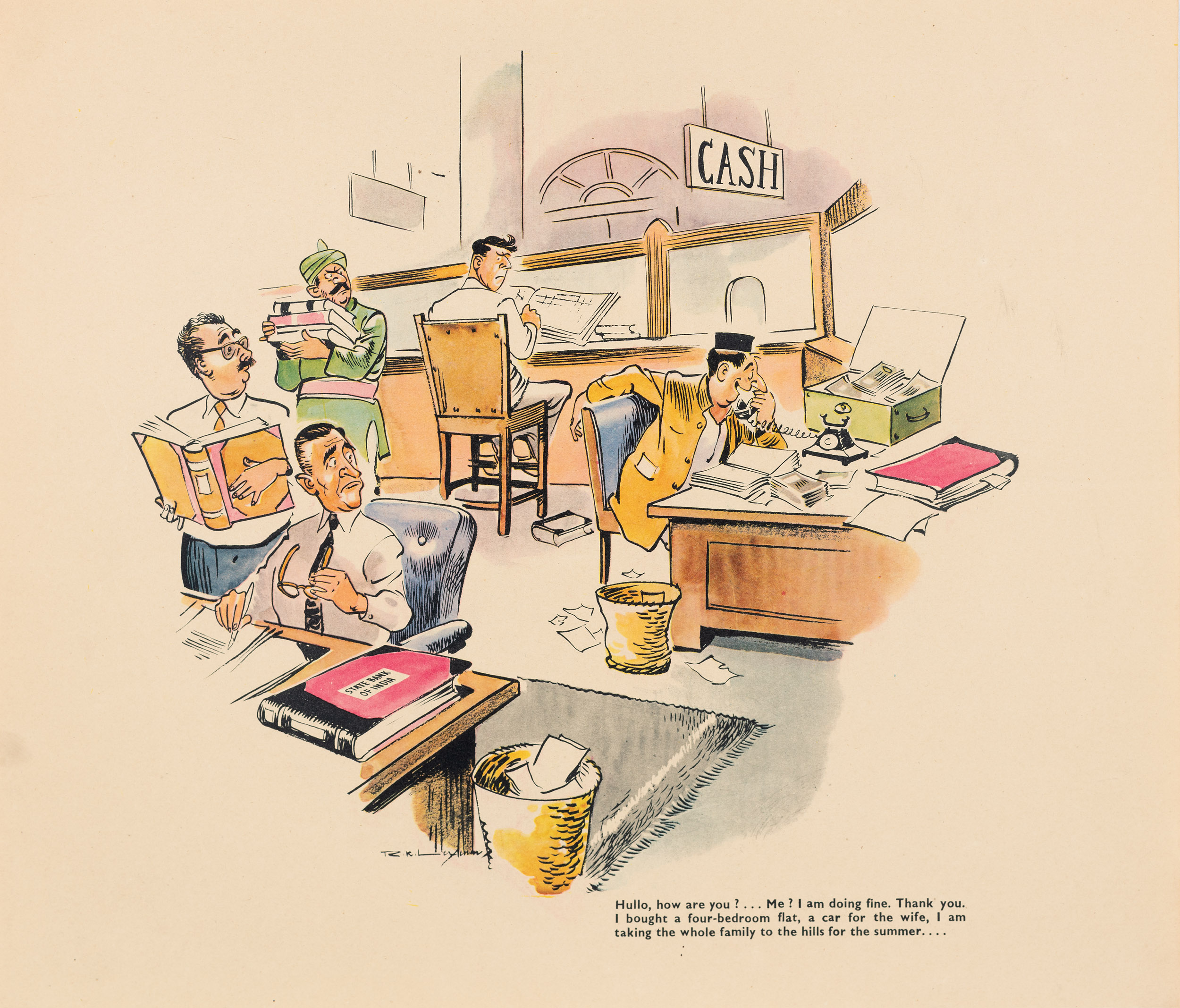

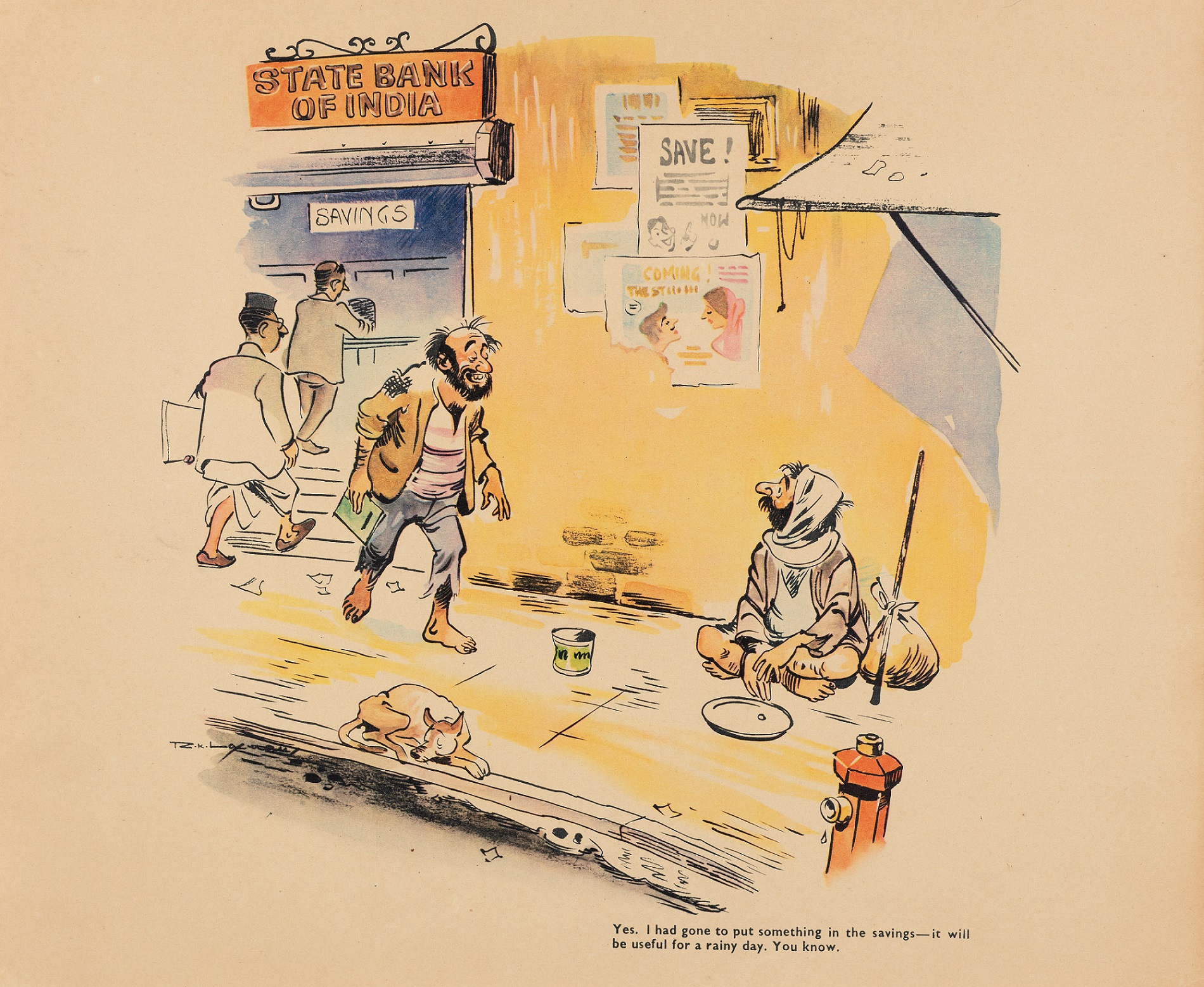

Most of the widely circulated cartoons by Laxman are monochromatic, which he sketched when he was working with publications like The Times of India at later stage in his life. Here, we take you through a series of his critically ignored coloured cartoons, which he created at a later stage of his career for the State Bank of India (S. B. I.). He depicted the flaws of the banking system in the country and how everyday life was affected by these policies, occasionally balancing his critique by depicting various positive aspects of the bank as well. 'The more one gets to meet people, the more knowledge and confidence one gains. He also observed things as a child—he observed them, understood people and their body language. The people he met later became well-known personalities like Jayalalithaa and musicians from the South like M. S. Subbulakshmi. Due to his brother, he met a lot of people in Mysore, which is a cultural city. He had a good background of cultural heritage, and his family molded him a lot in his early days.’--Usha Laxman, co-founder of the R. K. Laxman Museum, Pune, in an interview with DAG |

|

|

Hullo, how are you?...Me? I am doing fine. Thank you. I bought a four-bedroom flat, a car for the wife, I am taking the whole family to the hills for the summer ...

R. K. Laxman

Mechanical reproduction on paper, 14.5 x 16.7 in.

Collection: DAG

Yes, I had gone to put something in the savings - it will be useful for a rainy day. You know.

R. K. Laxman

Mechanical reproduction on paper, 13.5 x 16.2 in.

Collection: DAG

Running on the BankUsha Laxman, his daughter-in-law and one of the founders of the R. K. Laxman Museum, which was inaugurated last year in Pune, said that his freelance work in corporate sectors like banking and management included colour, as did his work for calendars. Laxman created twelve cartoons for a calendar that the S. B. I. published. They were also possibly included in book by R. K. Seshadri, who has written on the banking sector, called ‘A Swadeshi Bank from South India: A History of the Indian Bank: 1907-1982’ (1982). In a scene set at the S. B. I, Laxman plays on the suspicion that most people harbor of bankers who can’t be disassociated from the corrupt moneylenders, despite the emergence of professional private and public banks. After all Laxman was drawing these for a bank he was also critiquing. He maintains a balance by dressing every employee in smart formals, with an air of professionalism around them. The second cartoon depicts the relationship between banks and account holders, which has been explored by many storytellers like Ruskin Bond in stories such as ‘The Boy who broke the Bank’ where a rumour that a bank was going bankrupt prompted the townspeople, including a beggar, to demand their money back. |

|

‘I could not read the jokes under the cartoons, which were in pen and ink by different artists with different styles. But I used to spend hours studying each and would critically judge their quality. This exercise helped me to develop a visual sense of humour and also the rudiments of perspective, drapery and human anatomy, without being conscious of these.’ -R. K. Laxman, The Tunnel of Time, 1998 |

|

R. K. Laxman, detail from a cartoon print. Mechanical reproducation on paper, 14.2 x 17.0 in. Collection: DAG |

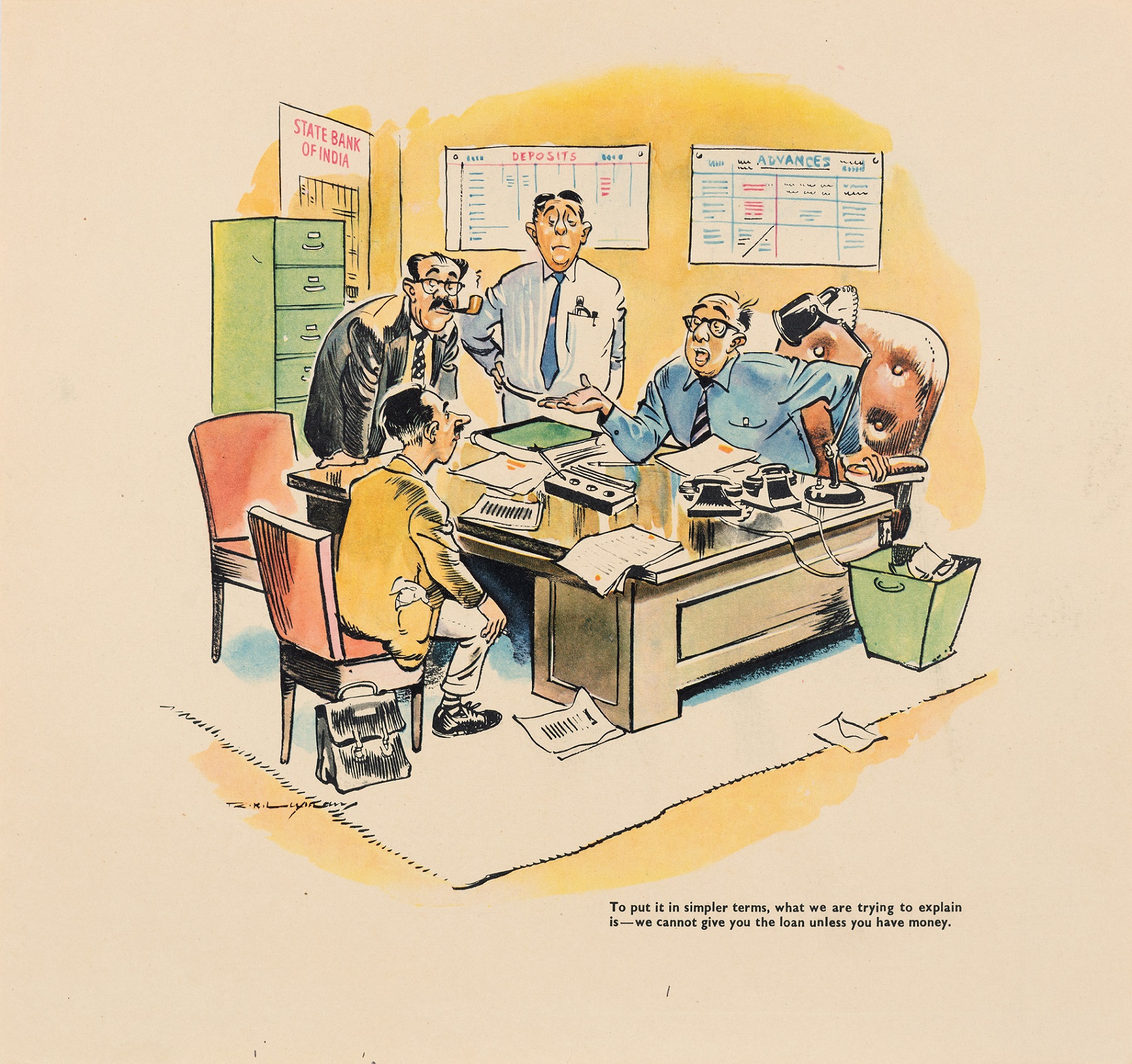

To put it in simpler terms, what we are trying to explain is – we cannot give you the loan unless you have money.

R. K. Laxman

Mechanical reproduction on paper, 14.5 x 16.7 in.

Collection: DAG

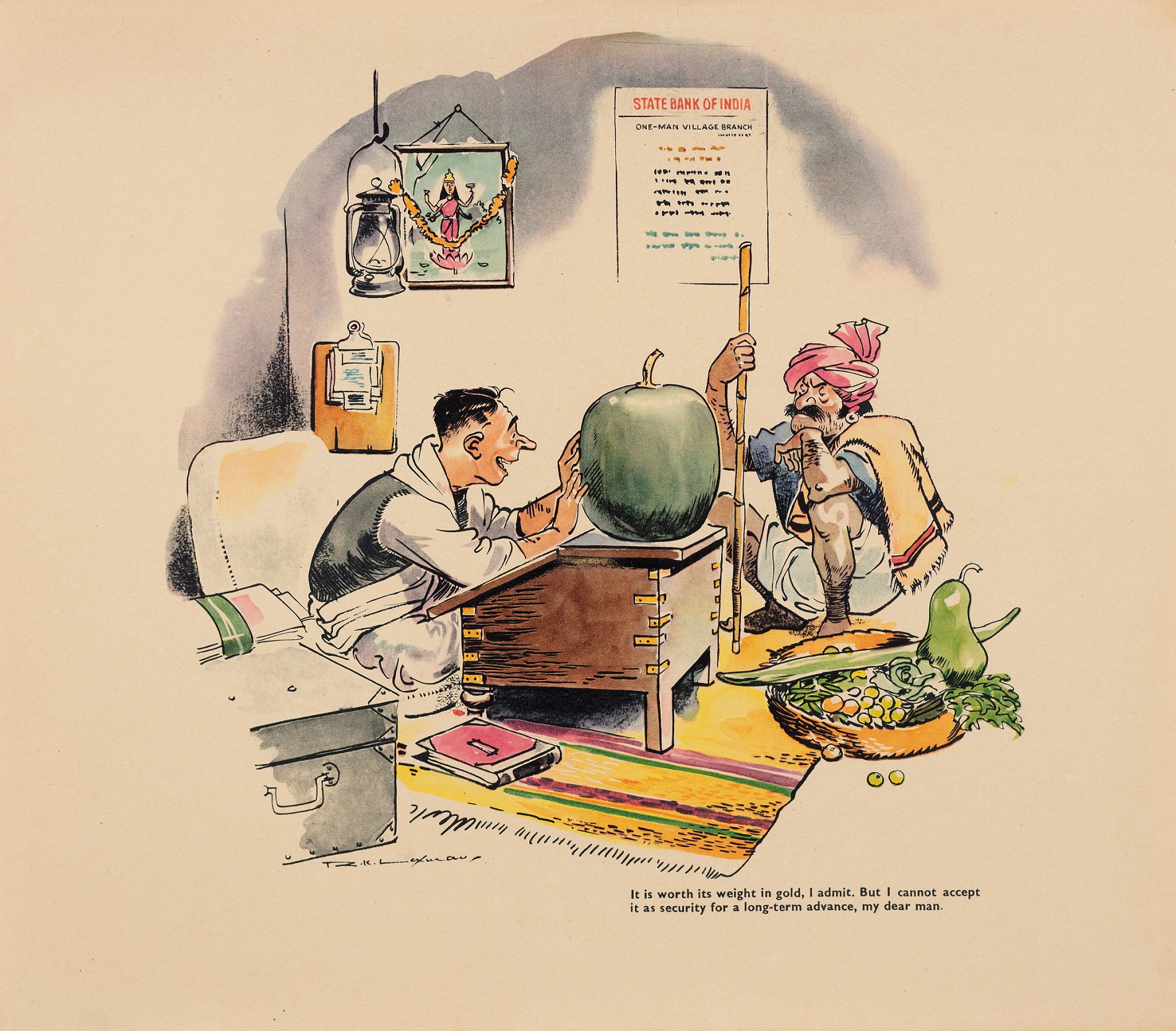

It is worth its weight in gold – I admit. But, I cannot accept it as security for a long-term advance, my dear man.

R. K. Laxman

Mechanical reproduction on paper, 14.5 x 16.2 in.

Collection: DAG

A Touch of ColourLaxman was fascinated with colours since his childhood, and often went to outdoor sessions with artists, sketching natural landscapes. When he was in high school, he started attending art classes taken by a teacher, who had graduated from the J. J. School of Art. Laxman was critical of the European style of painting followed in art academies and institutions—finding that ‘high art’ didn’t give him the space to express his reality. Here, he points out the difficulty of getting a loan from the bank in rural India. He uses embedded pictorial devices like the poster on the wall to tell us that the absurd exchange between the farmer and banker is happening at a ‘One-man village branch’, but the aspiration for financial inclusion is left unfulfilled. The conundrum of needing wealth to generate greater wealth extends to a middle-class customer at another State Bank branch in the city. Once again balancing his critique, he makes us see the clever professionalism of the bank employees through the meticulous cataloguing of their daily dealings—they do not miss a thing. |

|

‘One day I discovered three broken glass panes. I had picked them up somewhere and hidden them from the elders, for they would never have let me handle objects with such razor-sharp jagged edges. Having secreted them away carefully in the subterranean depths of the box, I had forgotten about them. I treasured them for their scintillating colours—red, blue and green. They offered me a whole world of magic turning the landscape into the colour I fancied when I peeped through them. I was thrilled to see the entire garden —trees, flowers, the gardener, his turban, shirt, bucket—drenched in green. The I turned the entire vista into grim red and set it aglow like an oven.’ -R. K. Laxman, The Tunnel of Time, 1998 |

|

|

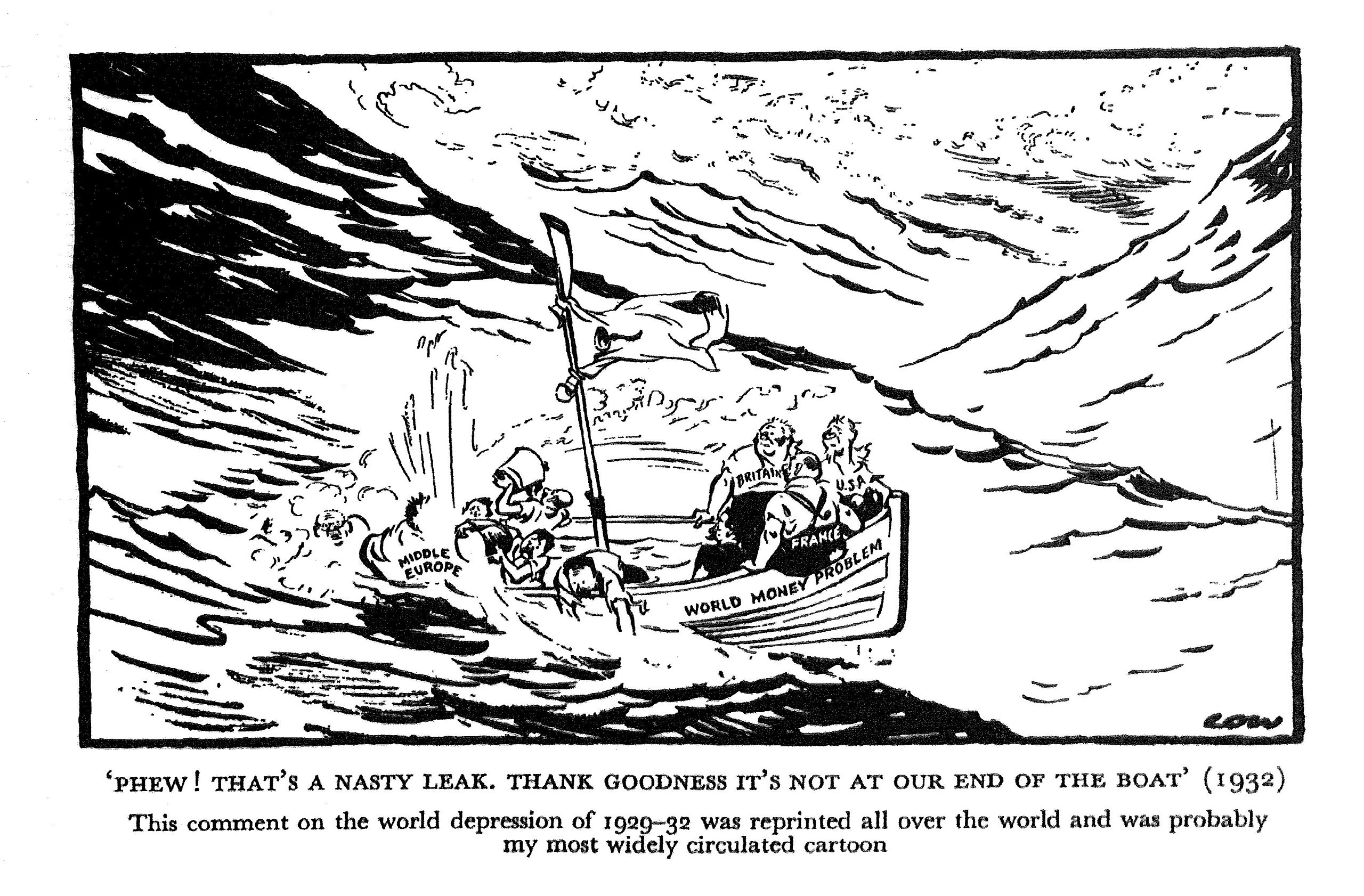

David Low, from his autobiography, 1932.

Low's cartoon reflects on the World Economic Depression of the 1930s, suggesting a link between his work and Laxman's focus on financial institutions and their impact on ordinary people.

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

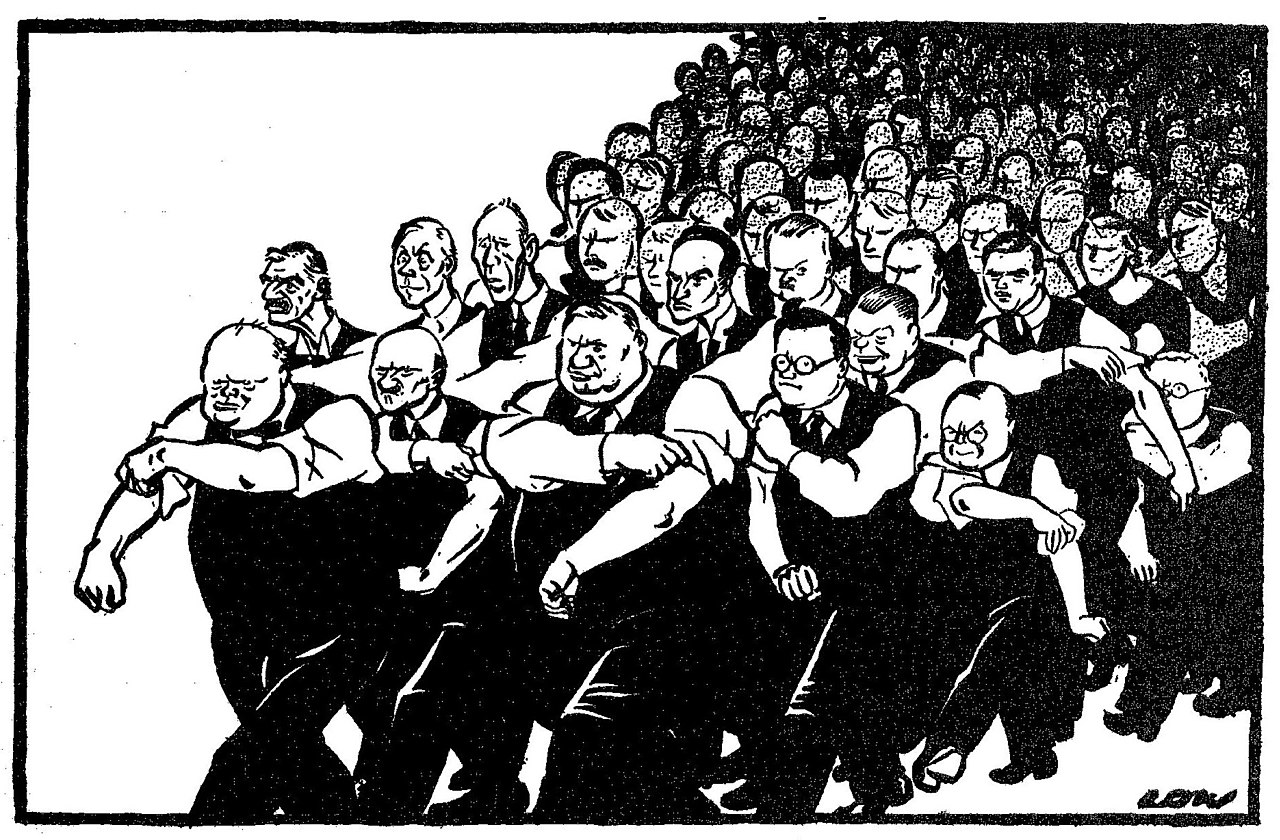

David Low, cartoon depicting Winston Churchill, Clement Attlee, Ernest Bevin and Herbert Morrison, 1940.

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

The influence of David LowWhen he was in school, he started illustrating his brother, R. K. Narayan’s short stories for The Hindu. He also illustrated a special issue for a college magazine, which caught the attention of M. Sivaram, the editor of Koravanji, a new satirical magazine in Bangalore. He called upon his services after seeing Laxman’s work on the cover. Koravanji This was inspired by Punch— A magazine where cartoonist David Low was a frequent contributor. Laxman was inspired by David Low’s cartoons since his middle school years, when he accidentally found his cartoons in a newspaper at home. For many years, he would follow the style of Low’s cartoons, the kind of sketching that was involved, the satire and minimal dialogue. Nala Ponnappa writes in the Economic and Political Weekly that it was only Laxman’s early cartoons which would bore similarities to Low. it can be argued that Low’s style, in fact, was visible in Laxman’s work all his life. This series, however, is quite different from Laxman’s regular style. He controlled the reader’s gaze by shading some portions of his sketch, while here, it borders on maximalism. Some of Low’s cartoons contain a single line of dialogue in one corner, which is what Laxman attempted too, in these works. |

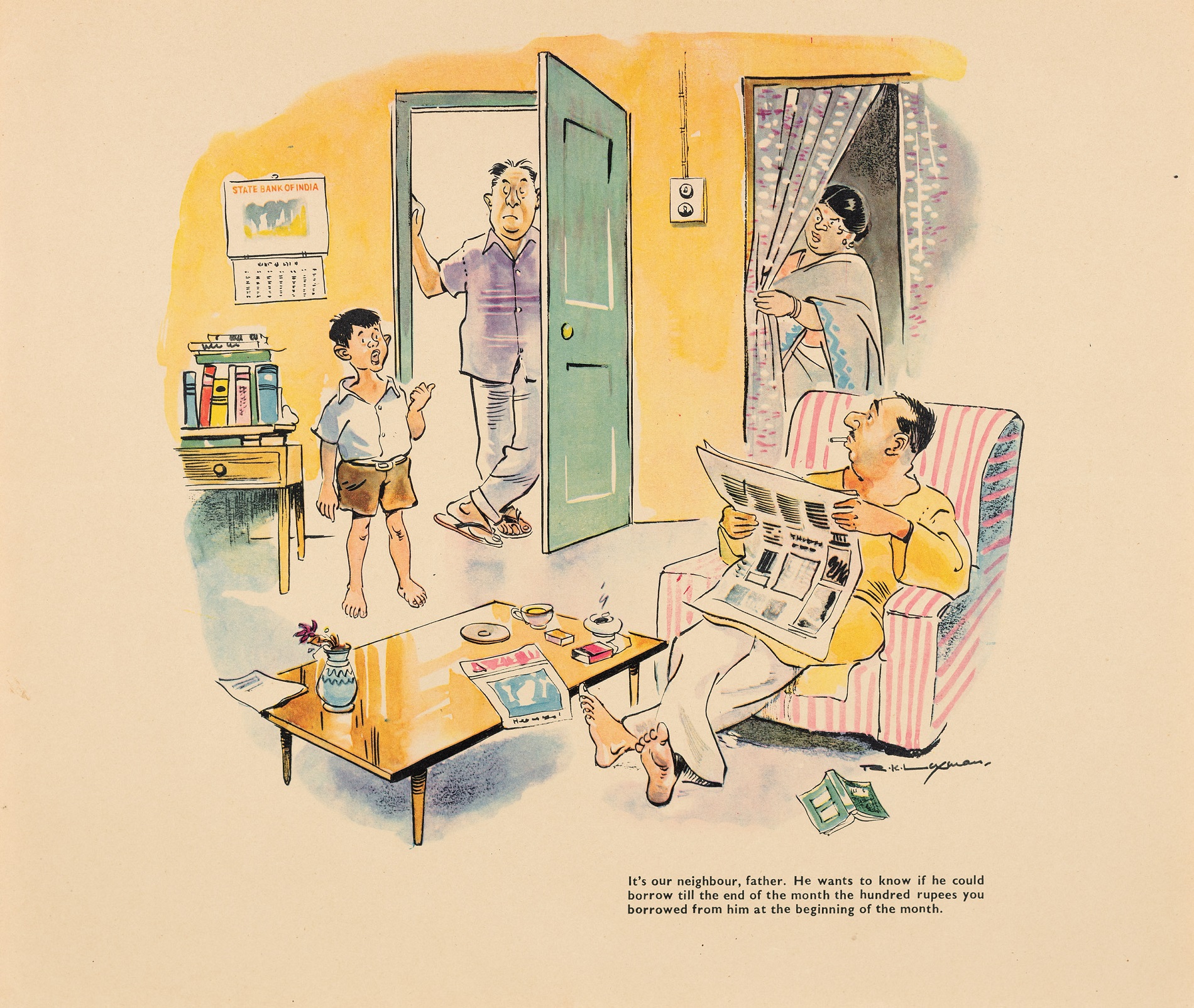

It’s our neighbor, father. He wants to know if he could borrow till the end of the month the hundred rupees you borrowed from him at the beginning of the month.

R. K. Laxman.

Mechanical reproducation on paper, 14.2 x 17.0 in.

Collection: DAG

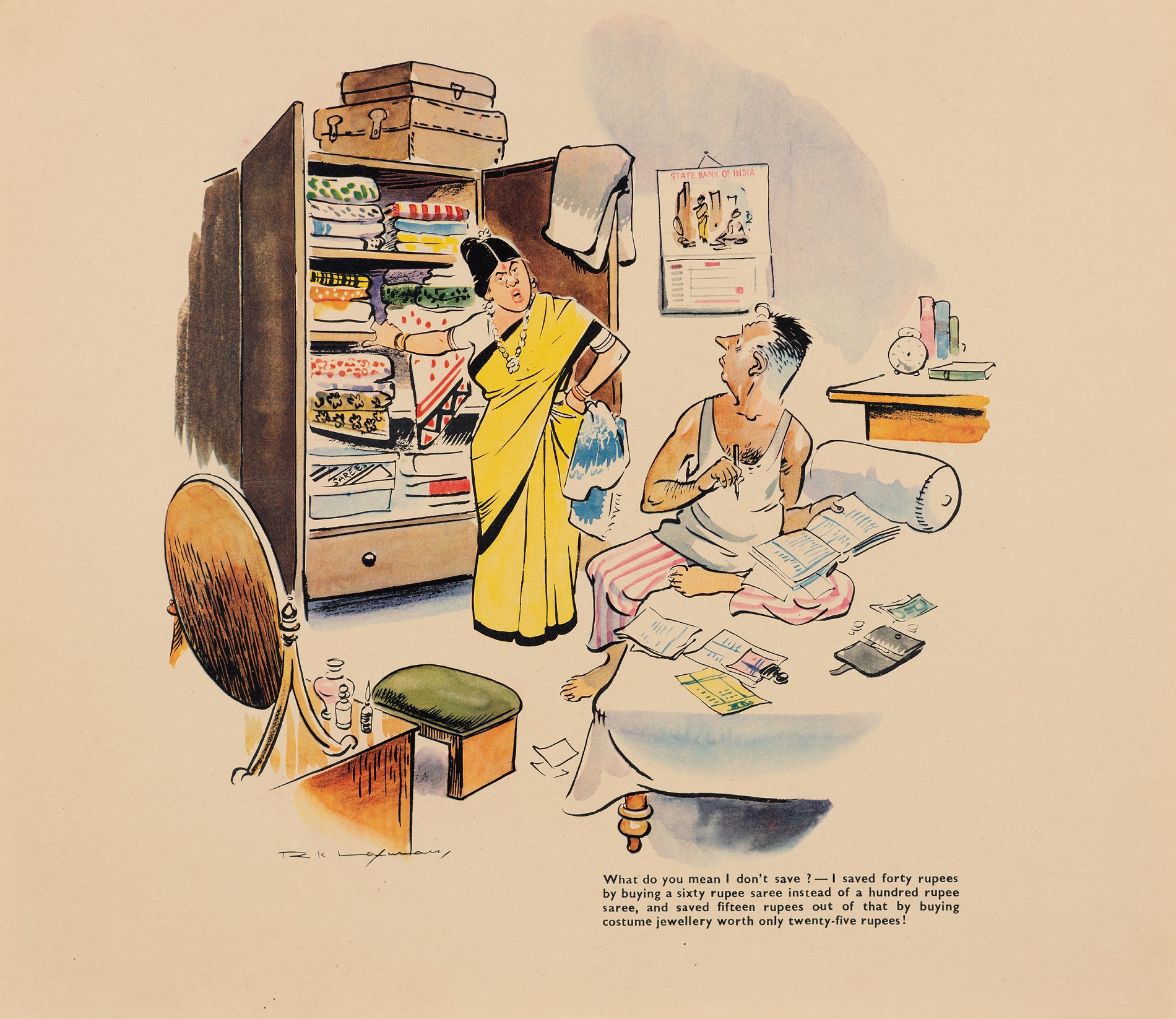

What do you mean I don’t save? – I saved forty rupees by buying a sixty rupee saree instead of a hundred rupee saree, and saved fifteen rupees out of that by buying costume jewellery worth only twenty-five rupees!

R. K. Laxman.

Mechanical reproducation on paper, 14.5 x 16.5 in.

Collection: DAG

Here, Laxman gives a snapshot of a middle-class household and reflects on the difficulty in getting loan money back. Here too, a State Bank calendar can be seen on the wall, cheekily relating larger questions of financial policy to everyday interactions and realities. Moreover, Laxman cheekily suggests the widespread influence of the bank within the middle-class home. All the cartoons have the S. B. I. calendar hanging from a wall. While a brilliant cartoonist, Laxman’s biases as a male artist cannot be missed, considering the second cartoon, where he imagines the middle-class Indian woman as someone who does not know how to manage her finances and is one of the prime reasons for most of the household expense. This is not a sentiment which Laxman alone held but reflects a prevalent stereotype. |

|

‘At this point of my life, I was not yet old enough to browse through the newspapers which everyone at home was passing from hand to hand and reading with great concentration. One day, by accident, I saw a cartoon opposite the editorial pages of the Hindu. I studied it. It made no sense to me, but the brilliance of its draftsmanship was stunning and held my attention for a long time...I looked at the name of this marvellous artist at the bottom of the cartoon. It was brief and bold and I read it as ‘cow’. From that day on I looked for the ‘cow’ cartoon. I spent hours gazing at the drawing and observing its finer points; the gentle caricature of faces, the effortless flow of lines, the perspective, the drapery—all done in controlled distortion—a masterpiece of visual satire...only much later, I learnt his name was not ‘cow’ but ‘LOW’—the world-renowned David Low.’ -R. K. Laxman, The Tunnel of Time, 1998 |

|

R. K. Laxman, Mechanical reproducation on paper, 14.2 x 17.0 in. Collection: DAG |

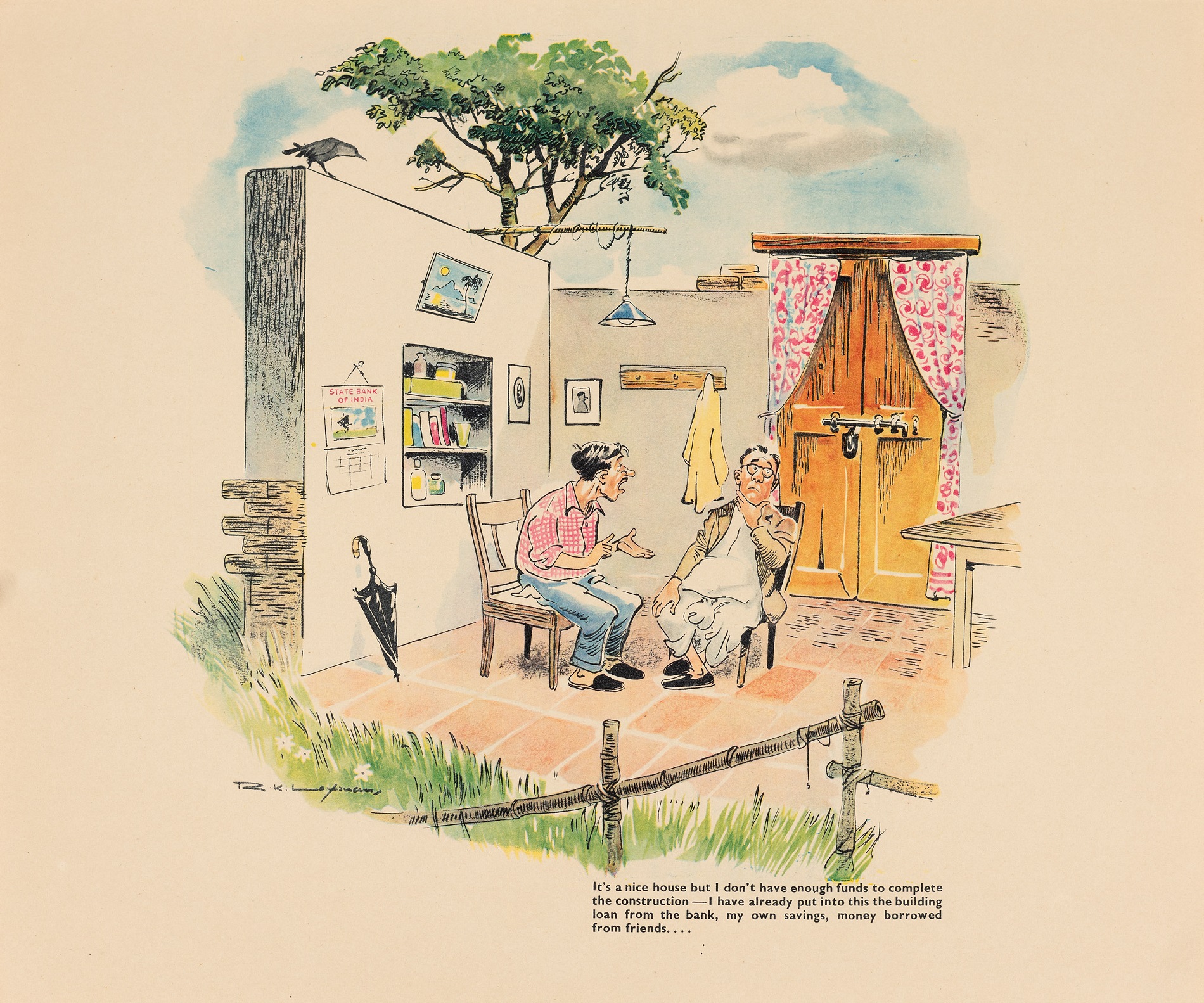

It’s a nice house but I don’t have enough funds to complete the construction – I have already put into the building loan from the bank, my own savings, money borrowed from friends…

R. K. Laxman.

Mechanical reproducation on paper, 14.5 x 17.0 in.

Collection: DAG

Caricature: An Inferior Art?While still in school, he entertained the desire to attend the J. J. School of Art. However, the J. J. School denied him admission since they did not consider his caricatures a serious form of art. Laxman would also not participate in local art competitions when he was younger since caricatures and cartoons were not allowed. When looking for work, he would face a different kind of prejudice. Laxman’s career, before he joined the Times would also reveal the inherent politics within newspaper offices, when he would not be offered a position even if his work was good, because the editor would be afraid that the current in-house cartoonist would not be too happy. After he went to see the editor of Hindustan Times, the editor was quite impressed with his work, but could not offer him a job and risk the ire of the veteran cartoonist. A cartoonist could not do anything with empty praises and the figures in his cartoons could not do anything without money. In this cartoon, he showcases a half-built house, construction on which was halted following a lack of finances. This was a common fate that many state-funded universities or even personal home projects had, where some floors were not built due to lack of funds. Construction resumed once funds were received. He does not seem to be praising S. B. I. in any way here. |

|

‘Suddenly the man (the editor of Indian Express) startled me by saying, ‘Why do you want to be a cartoonist? What’s so great about it? Why not take up another job! Why a cartoonist!’ -R. K. Laxman, The Tunnel of Time, 1998 |

|

|

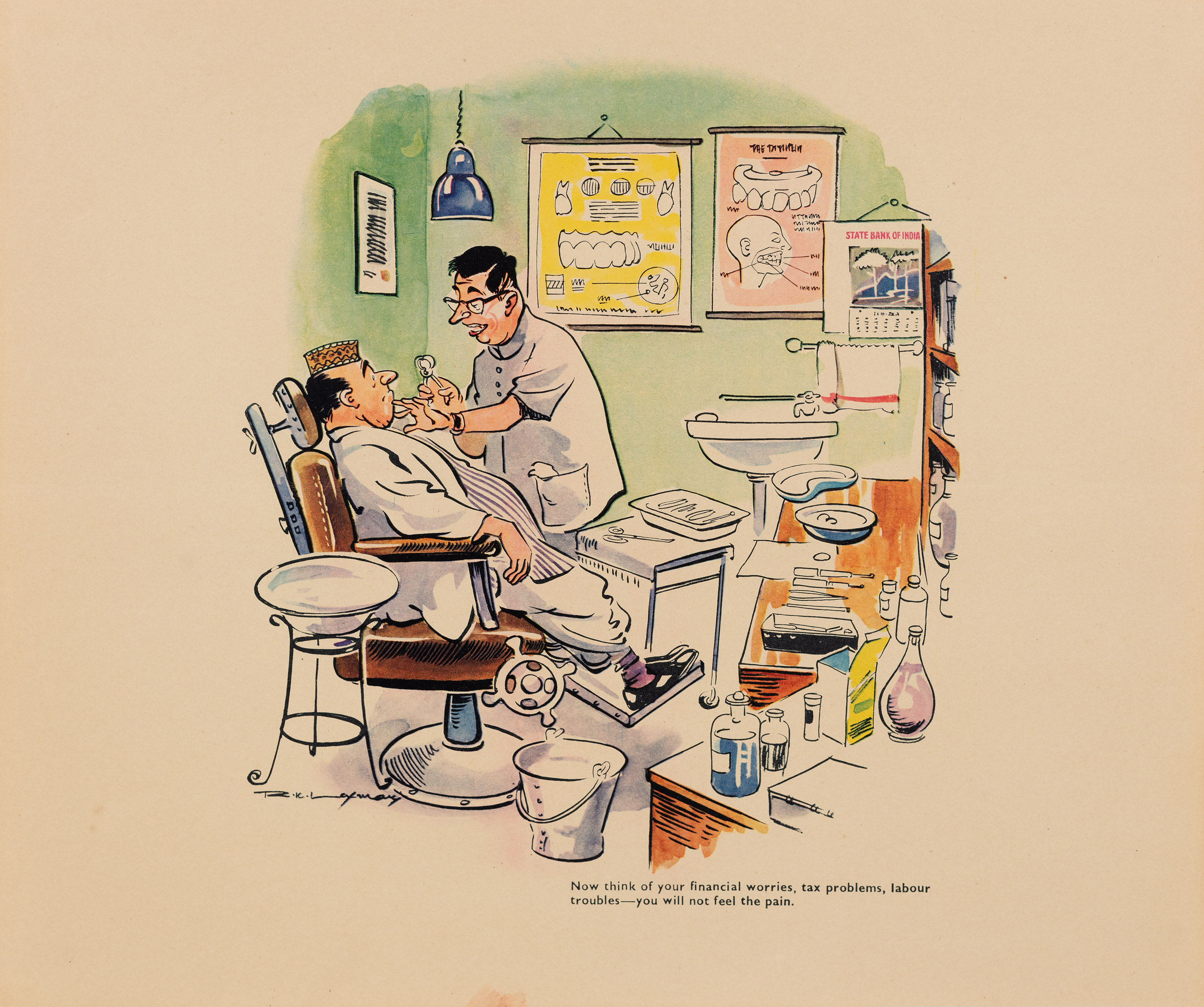

Now think of your financial worries, tax problems, labour troubles – you will not feel the pain.

R. K. Laxman.

Mechanical reproducation on paper, 14.0 x 17.0 in.

Collection: DAG

After Laxman completed his studies from Maharaja’s College, University of Mysore, he was always on the lookout for freelance work which could also cover his expenses of living in the different cities he resided in. Laxman was from a wealthy family, but occasionally he struggled with money, which led to his brother writing a short story on him called ‘Dodu the Money Maker’ about a boy who needed money to buy peanuts. For Laxman, in high school, money seemed to be an aspect which preoccupied him a lot, as seen in this cartoon, among the other themes that he was working with. Managing finances was truly like pulling teeth. |

|

‘Dodu was eight years old and wanted money badly. Since he was only eight, nobody took his financial worries seriously. (He wanted money for many things–from getting a good stock of Chinese crackers for the coming Deepavali to buying a fancy pen-holder which his master at school was forcing on everybody at the point of the cane.) Dodu had no illusions about the generosity of his elders. They were notoriously deaf to requests. They jingled with coins when they moved about. And yet they were astonishingly niggardly.’ -R. K. Narayan, Dodu the Money Maker |

|

|