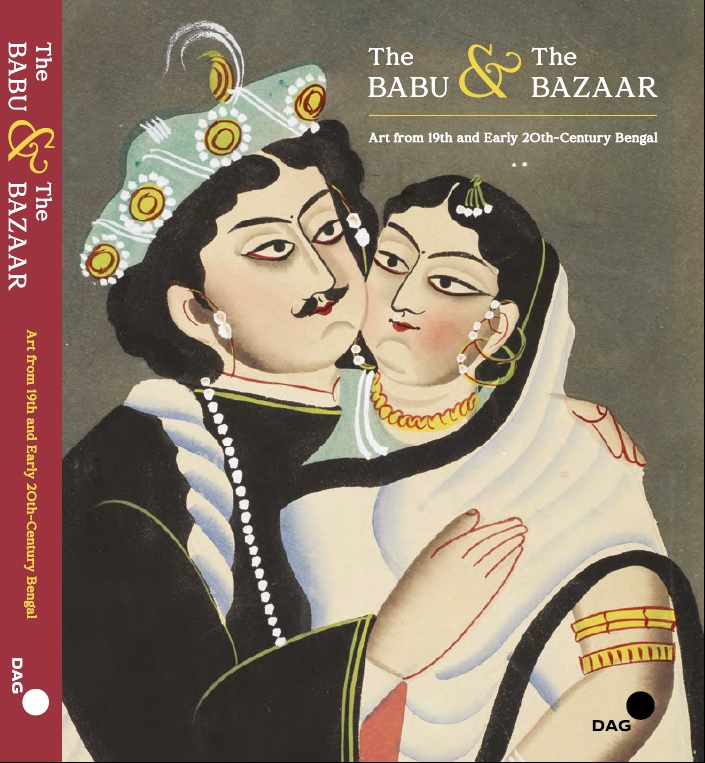

The Babu and the Bazaar: Art from 19th and Early 20th Century Bengal

The Babu and the Bazaar: Art from 19th and Early 20th Century Bengal

The Babu and the Bazaar: Art from 19th and Early 20th Century Bengal

|

The Babu and the Bazaar: Art from 19th and Early 20th Century Bengal The Alipore Museum Kolkata, 26 September 2025 - 14 February 2026

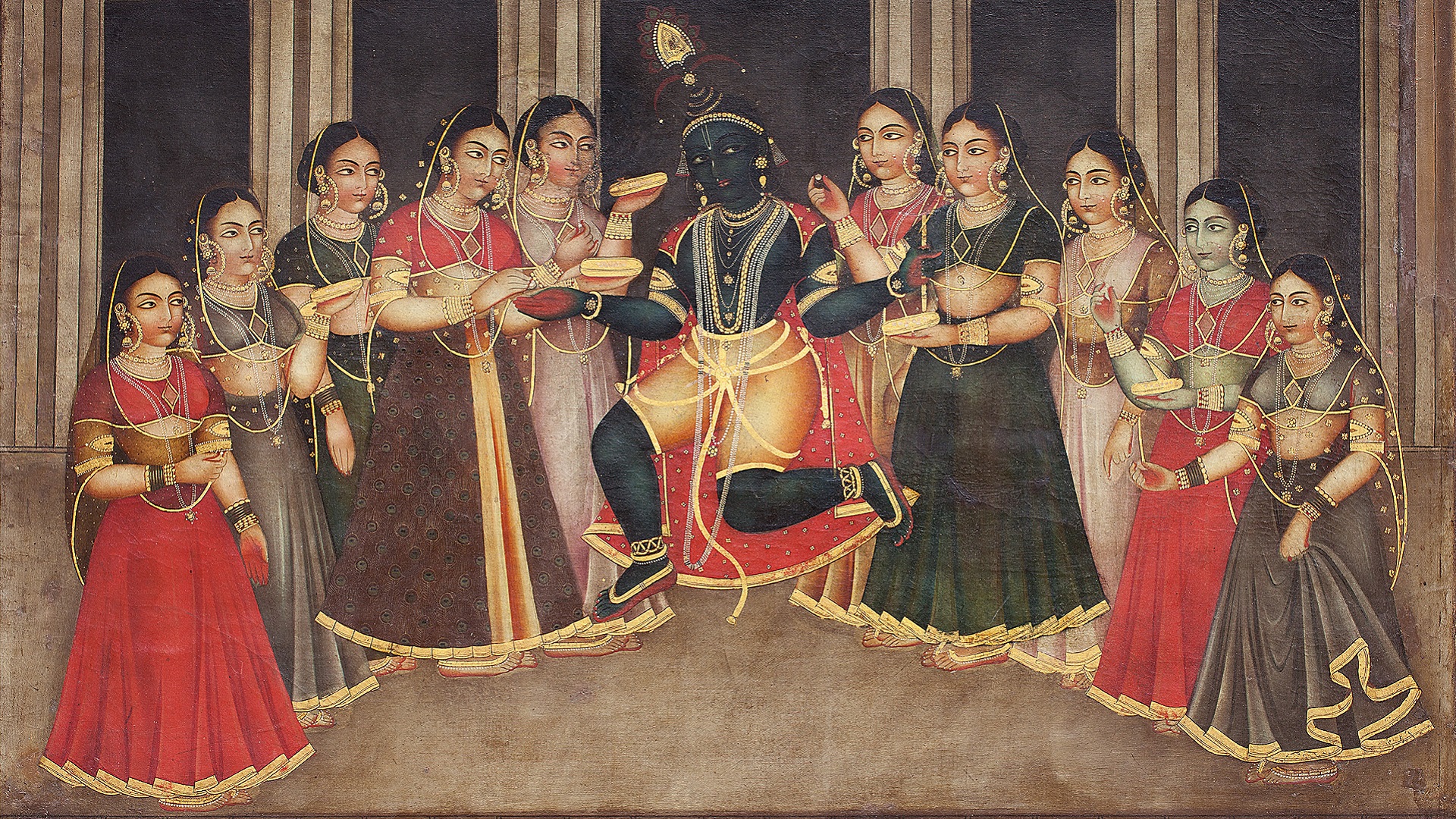

Kasturbhai Lalbhai Museum Ahmedabad, 22 October - 3 December 2023 Exhibition by DAG Unidentified Artist Krishna with Gopis Oil highlighted with gold pigment on canvas |

|

In 'The Babu & the Bazaar: Art from 19th and Early 20th-Century Bengal', watercolour Kalighat pats—both religious and secular—are placed alongside comparable works across the genres of commissioned oil painting and mass-produced prints, as well as a small grouping of reverse-glass paintings of possible Cantonese origin. By exploring iconography, the exhibition attempts to unravel part of colonial Calcutta’s history, its culture, class biases and gendered hierarchies. The presented collection is of historical objects, made by (mostly) unnamed artists as items of commerce close to, or more than one hundred years ago. They preface the advent of the individual modern Indian artist of the twentieth century but appear after the initial wave of European artists during the eighteenth century. Effectively, this collection may be called ‘early’ modern Indian art due to the hybrid techniques, mediums and painting surfaces utilised. |

|

Unidentified Artist Krishna as Boatman Oil highlighted with gold pigment on canvas |

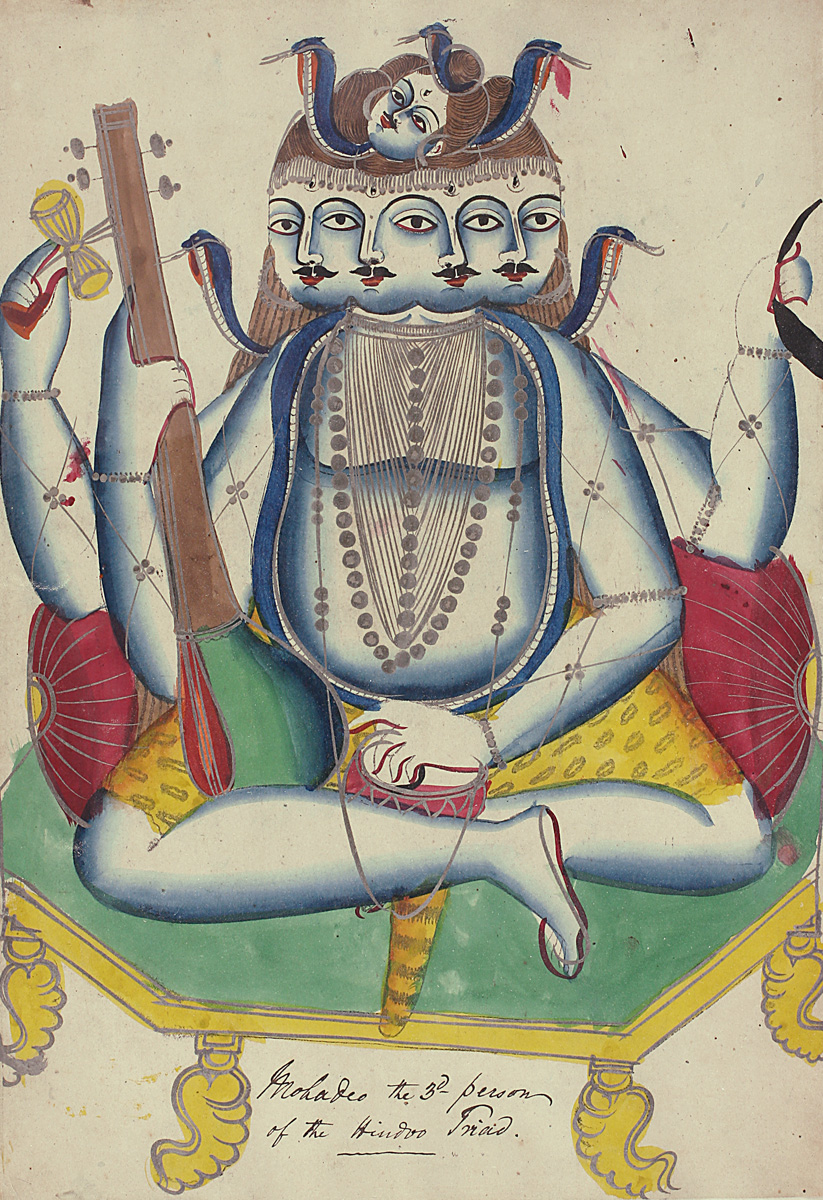

Unidentified Artist

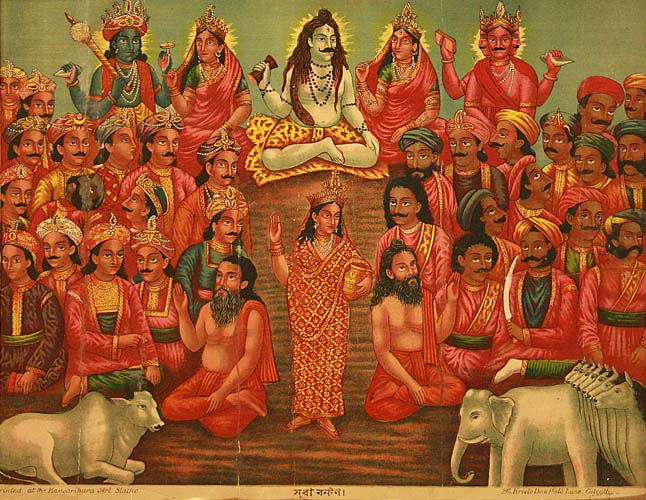

Shiva Panchanan, c. late 19th century

Watercolour over lithographed outlines, highlighted with silver pigment on paper

Unidentified Artist

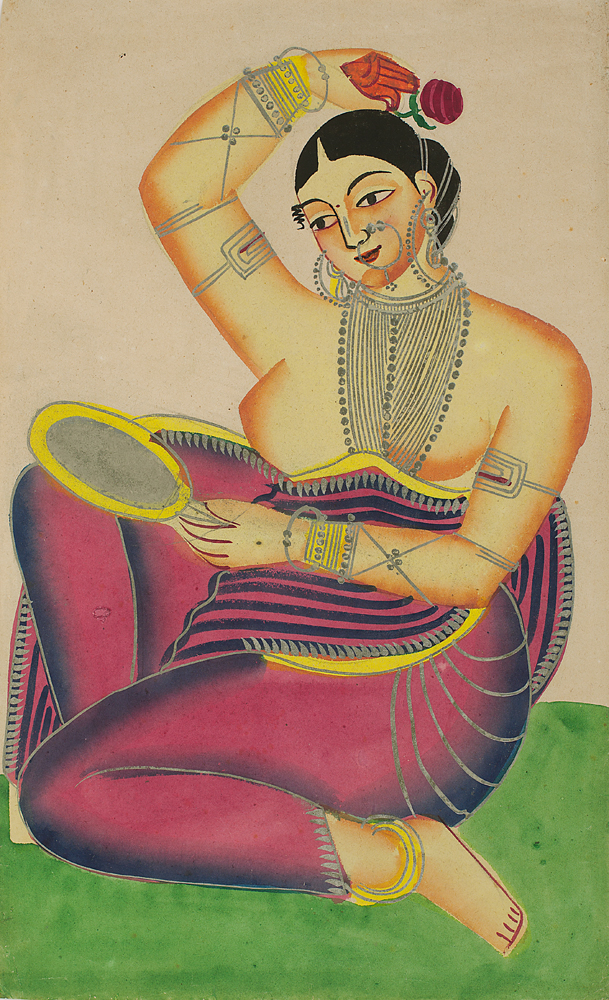

Shundari, c. late 19th century

Watercolour highlighted with silver pigment

Unidentified Artist

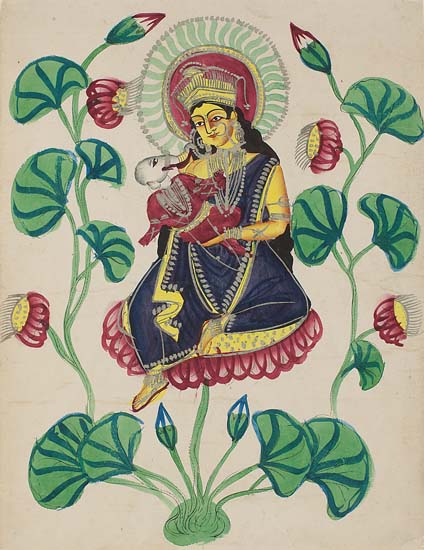

Raj Rajeshwari, c. late to middle 19th century

Oil on canvas

Unidentified Artist`

Golaap Shundari, c. late 19th century

Oil on canvas

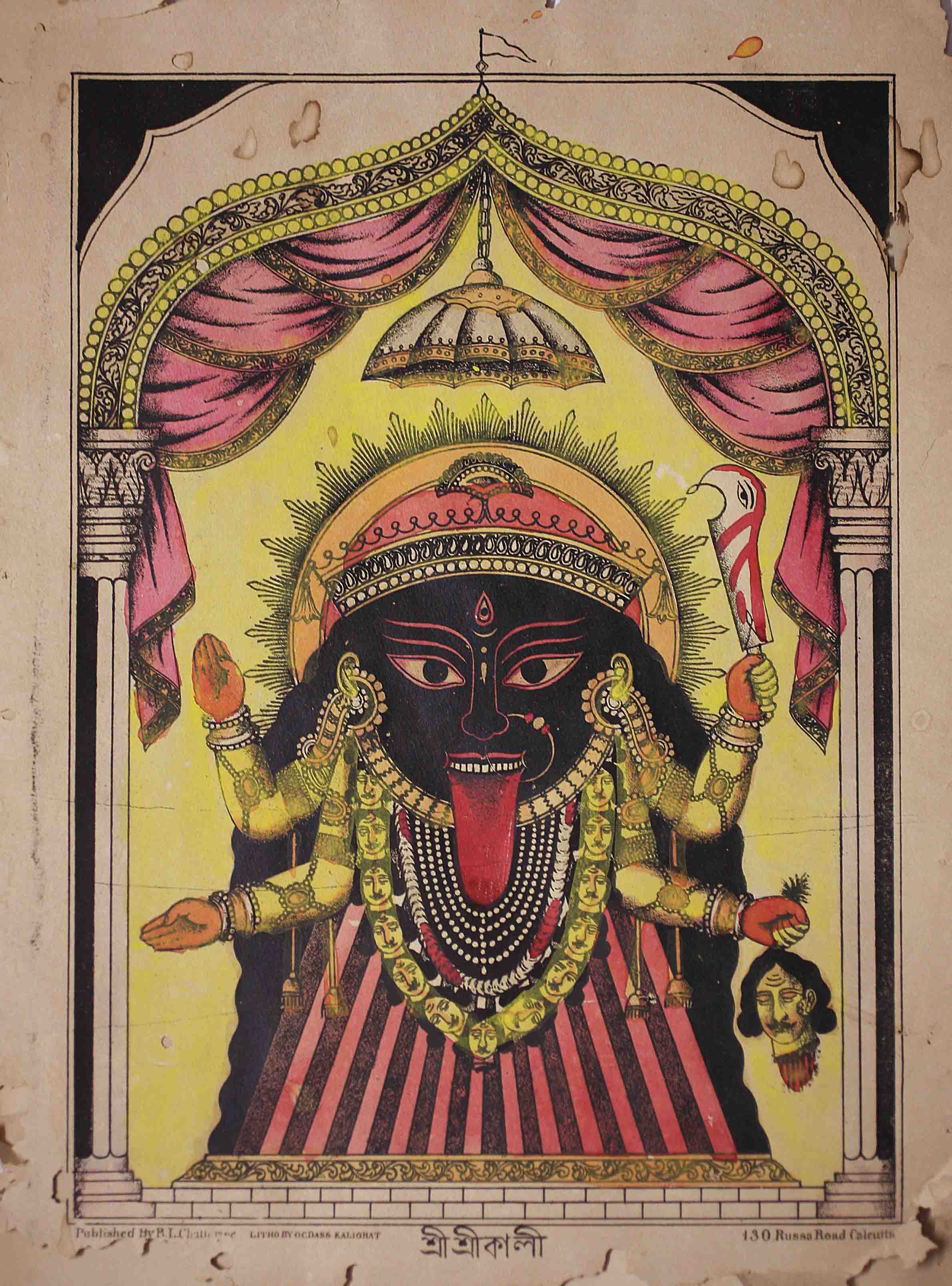

G. C. Dass

Shri Shri Kali, c. middle to late 19th century

Lithograph, tinted with watercolour on paper

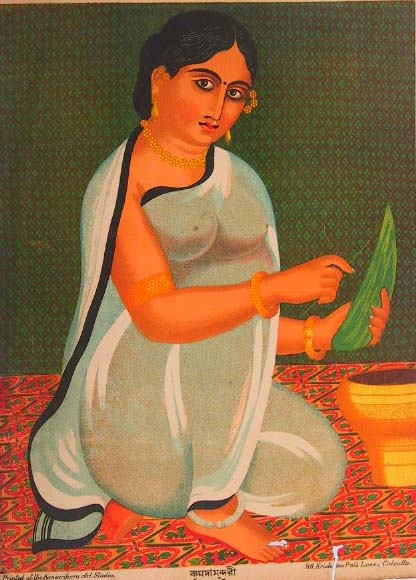

Kansaripara Art Studio

Paan Shundari, late 19th century

Chromolithograph on paper, pasted on paper

During the nineteenth century, two distinct cultures developed within Calcutta—that of the masses and that of the moneyed—with stark differences and rivalry. The nouveau-riche ‘babu’ was satirised as a deracinated man unaware of worldly problems. Likewise, the babus or English-educated Calcutta ‘bhadralok’ found popular culture lewd and uncivilised. Art reflected this division between ‘high’ and ‘low’ cultures. Today, it affords us an intriguing view of the city and its people, poised between tradition and modernity. |

|

POPULAR PAT PAINTINGS The Kalighat patuas or pat painters, who may have arrived in Calcutta from neighbouring villages of Bengal, remain mostly anonymous. We surmise that many came from family ateliers producing clay images and narrative pat scrolls. The artists painted on paper, using both synthetic and naturally obtained pigments: leaves from broad bean plants, indigo powder, grated turmeric, powdered conch-shell, extracts of betel leaves mixed with lime and catechu, root of the gab tree, hibiscus and palash flowers, as well as lamp-black. At its zenith, rang (colloidal tin) was used to embellish each image. The paintings mostly depicted divine iconography, like the Kalighat Kali, Durga, Jagaddhatri, Shiva, Vishnu, and other gods. |

|

Unidentified Artist Amorous Couple Watercolour on paper |

Unidentified Artist

Kamaley Kamini

Unidentified Artist

Dakshinakali

Unidentified Artist

Sheyal Raja

|

EARLY OIL PAINTING IN BENGAL A genre of indigenous oil painting developed across Bengal’s different colonies in the nineteenth century. At times comparable to the pats in subject matter, iconography, and even in the style of execution, they catered exclusively to Indian elites—the babu, the baniyan, and the zamindar. The oils underwent considerable changes during the nineteenth century, as better means of technical education were made available. Some appear closer to the miniature tradition—with foreshortening and flattened perspective—while others employ a visibly more Western, naturalistic technique. More than being merely decorative objects, they served a utilitarian purpose for the devout Hindu who could afford them. Placed within damp temple-rooms and used for daily worship, the paintings were constantly exposed to soot and smoke from censers and incense sticks, causing them to develop a fine leathery craquelure. This art was considered ‘high’ as it invoked the divine and was in the general criteria for bhadrata that elites outwardly promoted. |

|

Unidentified Artist Balarama and Krishna at Vrindavan Oil highlighted with gold leaf on canvas |

Unidentified Artist

Kurukshetra War

Unidentified Artist

Madan Bhasma

Unidentified Artist

Balarama and Krishna at Vrindavan

Unidentified Artist

Paan Shundari, late 19th century

Oil on Canvas

The only non-religious oil paintings are of sundaris, most certainly modelled after Kalighat pats or popular lithograph prints and meant to adorn the walls of the dancing parlour. Caricature, which formed a considerable part of the popular traditions, is missing from this genre, as the object of ridicule was always the babu. |

|

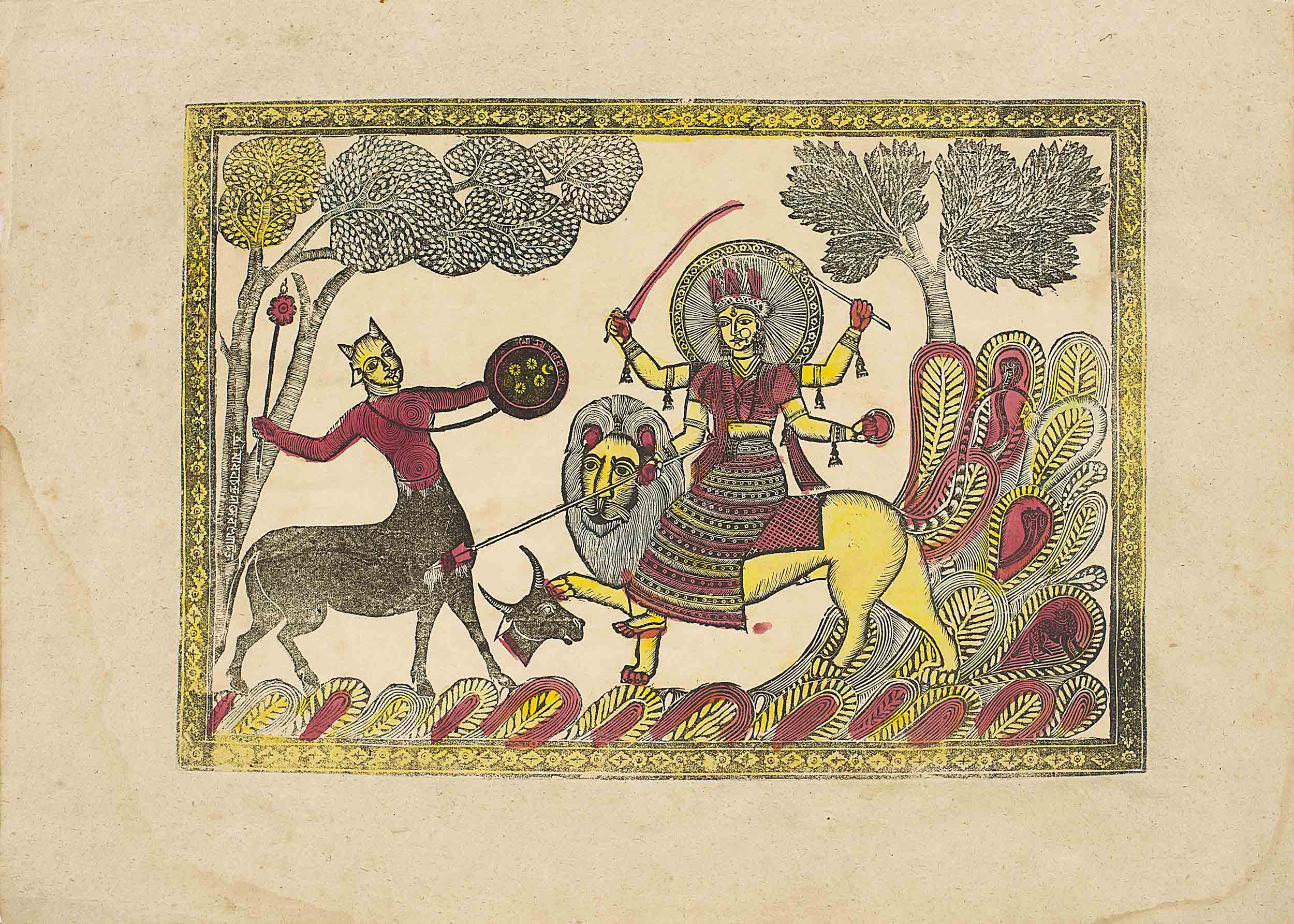

EARLY POPULAR PRINTING IN BENGAL Woodblock and metal-engraved illustrations, indispensable to the vernacular presses of nineteenth-century Calcutta, were also sold individually. Printed with black ink, some were hand-tinted with broad daubs of coloured pigment. Many may be compared in design to the pat paintings, although it is unknown whether watercolour artists and engravers worked in unison or one was copying popular designs of the other. Quite unlike the pat and oil artists, engravers and publishers added their names onto their designs. |

|

Madhav Chandra Das Mahisasurmardini Woodcut tinted with natural dye on paper |

Nritya Lal Datta

Dakshinakali

Kansaripara Art Studio

Sudha Bantan

Madhav Chandra Das

Mahisasurmardini

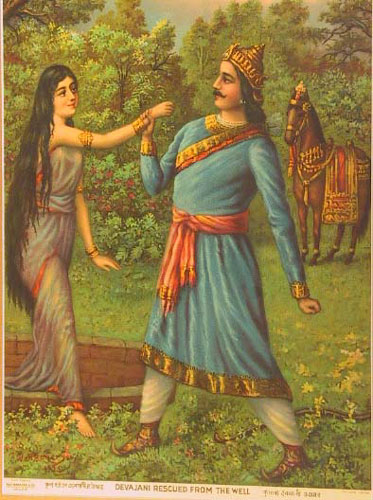

Annada Prasad Bagchi

Bijoya

Bamapada Banerjee

Devajani Rescued from the well

Near the end of the nineteenth century, litho and oleo prints rapidly took over the market. Artists like Annada Prasad Bagchi and Bamapada Banerjee, armed with technical art education from the art college, produced prints on similar themes but undertaken with a high standard of academic fidelity. Many lithography presses subsequently rapidly spread in Calcutta, while oleographs by German printers showing Indian themes were imported into the city. Among them we find Calcutta Art Studio, Kansaripara Art Studio, Chorebagan Art Studio, Jubilee Art Studio, and Imperial Art Cottage. Most printing houses presented comparable images for sale, but with subtle variations in design.

|

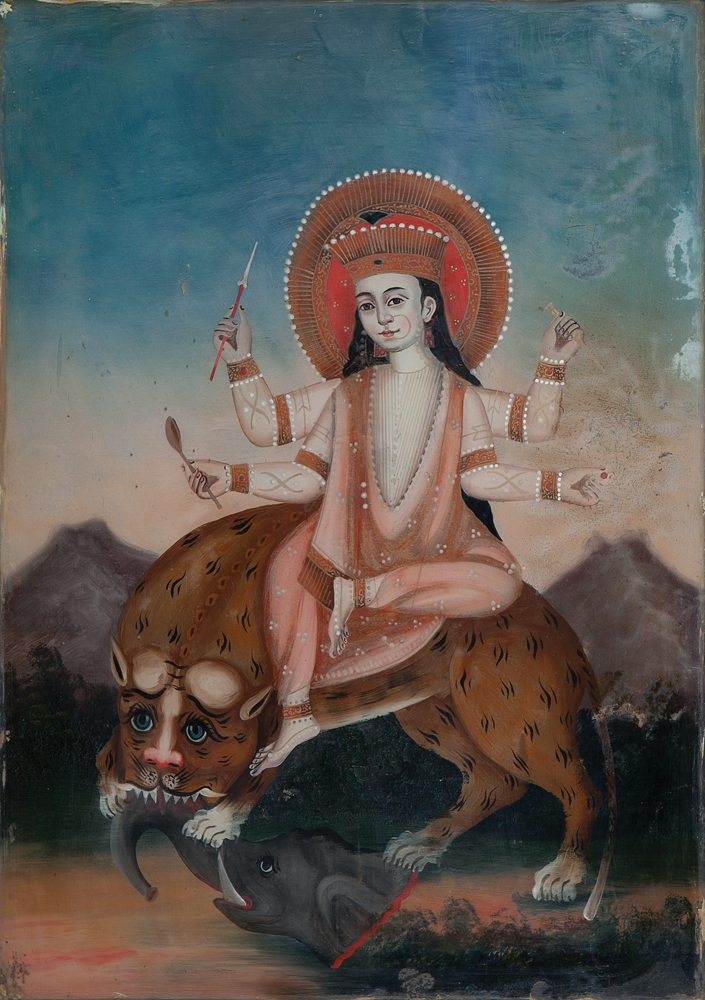

GLASS PAINTINGS Reverse glass paintings became popular across India in the nineteenth century, though some were initially likely to have been painted in Canton (present-day Guangzhou in China) and used for peddling merchandise in India—hence the choice of sacred iconography, however erroneous. It is assumed this art was at first introduced to India in the eighteenth century by Chinese or Parsi traders along the western coast, but their popularity would spread across the subcontinent in the next hundred years. When choosing pictures that would sell in the markets of Calcutta, the pat watercolour paintings were used as template, perhaps for their relatively uncomplicated iconography. All paintings comprise a similar palette, primarily of red and blue pigments, with a generic mountain added to the backdrop. |

|

Unidentified Artist Ganga Gouache, highlighted with gold and silver pigments |

Unidentified Artist

Ganga

Unidentified Artist

Jagaddhatri

Unidentified Artist

Annapurna

|

"There are several reasons that the ongoing exhibition at DAG, The Babu & The Bazaar, stands out. For one, it offers a sweeping view of the art in 18th-19th centuries Bengal—from Kalighat pats and oil paintings to early printmaking and the rare reverse paintings on glass. Curated by historian and scholar Aditi Nath Sarkar, the show, and the accompanying publication, also shed light on the sociocultural ethos of the time, be it the class biases, gendered hierarchies, Kolkata’s history or the constant tussle between tradition and modernity." "An exhibition that spotlights the female figure in early Bengal art", Mint Lounge, 6 June, 2023 "Only when you step out of lift into the avant garde space of DAG in Delhi do you sense an exploration of essence, a sensorial epoch, and a perception of beautiful Bengal. In the past few years, DAG and CEO Ashish Anand have sought to combine these perspectives, by focusing in on the iterative, pairing it down to the minimal and ultimately striving to reach for an essence while also pursuing the idea of movements and periods which is innate in the texts and practices of ancient Indian art." "A banquet of lotus leaves and goddesses in the Babu & the Bazaar exhibition", The Times of India, 25 May, 2023 |

Presented by