Asian Travellers: Mukul Dey and Yoshida Hiroshi AbroadThe Editorial Team May 01, 2024 While the process of exchange between India and Japan relied on the dissemination of artworks, texts and concepts between these two locations, they also required the physical exchange of bodies as artists from India went to learn from their Japanese counterparts and Japanese artists made their way to India. In other words, a critical cosmopolitanism was being forged with the help of these exchanges that could promote learning from each other while claiming the right to be critical too. In this photo essay we will follow the trajectories of two such artists—Mukul Dey and Yoshida Hiroshi—who learned from the other’s aesthetic culture and tradition. |

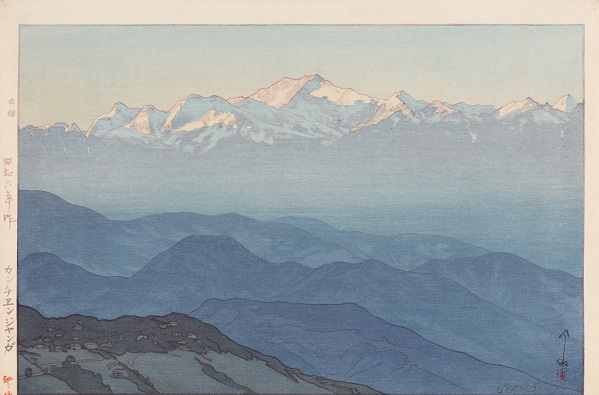

Yoshida Hiroshi

Kinchinjanga / Kanchang (Kangchenjunga)

1931, Kokka woodblock print on paper, 9.7 X 14.7 in.

Collection: DAG

|

An Indian artist who gained from this moment of cultural exchange was Mukul Dey. He was chosen by Rabindranath Tagore as a travelling companion during his trip to Japan (and the United States) in 1916, when Dey was just twenty-one years old. Dey wrote about his experiences in Japan in letters and autobiographical texts, giving us a glimpse into this unique cultural moment between two Asian nations even though one of them was still under colonial occupation. |

|

|

Mukul Dey

Sakuntala's Farewell to the Trees and the Flowers of her Home

Drypoint on paper, 11.7 X 6.5 in.

Collection: DAG

During his Japan sojourn Dey stayed with Taikan Yokoyama, the Japanese artist, who encouraged the younger Indian artist to make a career in art. The letters and diary entries recorded by Dey provide a glimpse into his daily activities, routines and invitations at various Japanese households. They tell us about the artists Dey lived with or met during his travels. In a letter he wrote to Gaganendranath Tagore on 8 June, 1916, for instance, he wrote:

|

|

Mukul Dey would write in his memoirs: ‘Wherever I saw paintings of Taikan or Shimomura, I realized that they didn't copy the European art or nor did they side with ancient Japanese arts. There were strong and courageous self expressions (sic). This is the place where they occupied supremacy. There is no exaggeration but vastness. The life is more valuable than imagination to them’. Japan was a site of such fertile aesthetic encounters for Dey. It generated confidence in his own efforts to learn from Indian cultural traditions, leading him to places like the Ajanta caves where he continued his artistic apprenticeship; and it also allowed him to move beyond the static mythological themes prevalent in Bengal’s art scene at the time (especially visible in the works of several students of Abanindranath), and tackle, instead, scenes of an everyday nature. Known as a master of the drypoint etching technique, he would translate his taste for the ‘vastness’ he encountered and admired in Japanese works to the landscapes of Bengal. |

|

|

Mukul Dey

Untitled

1930, Drypoint on paper, 8.7 X 10.2 in.

Collection: DAG

Mukul Dey

Untitled

Drypoint on paper pasted on cardboard, 8.0 X 12.0 in.

Collection: DAG

Mukul Dey

Untitled

1948, Watercolour on paper, 6.0 X 8.0 in.

Collection: DAG

As a historian recounted, ‘Arai Kampo had to stay at Ajanta for some days to copy the frescos. During Kampo’s stay in Ajanta in July 1917, Mukul Dey visited Ajanta to heal the sorrow of losing his father. They unexpectedly met each other at Ajanta. Arai Kampo wrote about this meeting with Mukul Dey in the following manner, ‘… screaming Arai san, Arai san, and suddenly one person jumped in front of me, the person was Mukul Dey.’ During this visit to Ajanta Mukul Dey experienced the beauty of nature, flowers, and waterfall at Ajanta which opened up a new door of art to him. He lived with Arai san at Ajanta and helped him in his endeavour as much as possible. In Ajanta's first cave, he was touched by the method of Arai san when copying the ‘temptation of Buddha’. Mukul Dey was moved by Arai san’s hardworking spirit day and night. Influenced by Arai Kampo, Mukul Dey too decided to copy Ajanta's fresco murals. After a few days, Mukul Dey left Ajanta and Arai Kampo also returned to Japan.’ Dey would return in 1919 and spend a year and a half making copies of the Ajanta murals. |

|

Yoshida Hiroshi was a renowned Japanese artist known for his exquisite woodblock prints, particularly landscapes and scenes from around the world. Born in 1876 in Kurume City, Fukuoka Prefecture, Japan, Hiroshi began his artistic journey at a young age, influenced by his father, who was also a painter and teacher. |

|

|

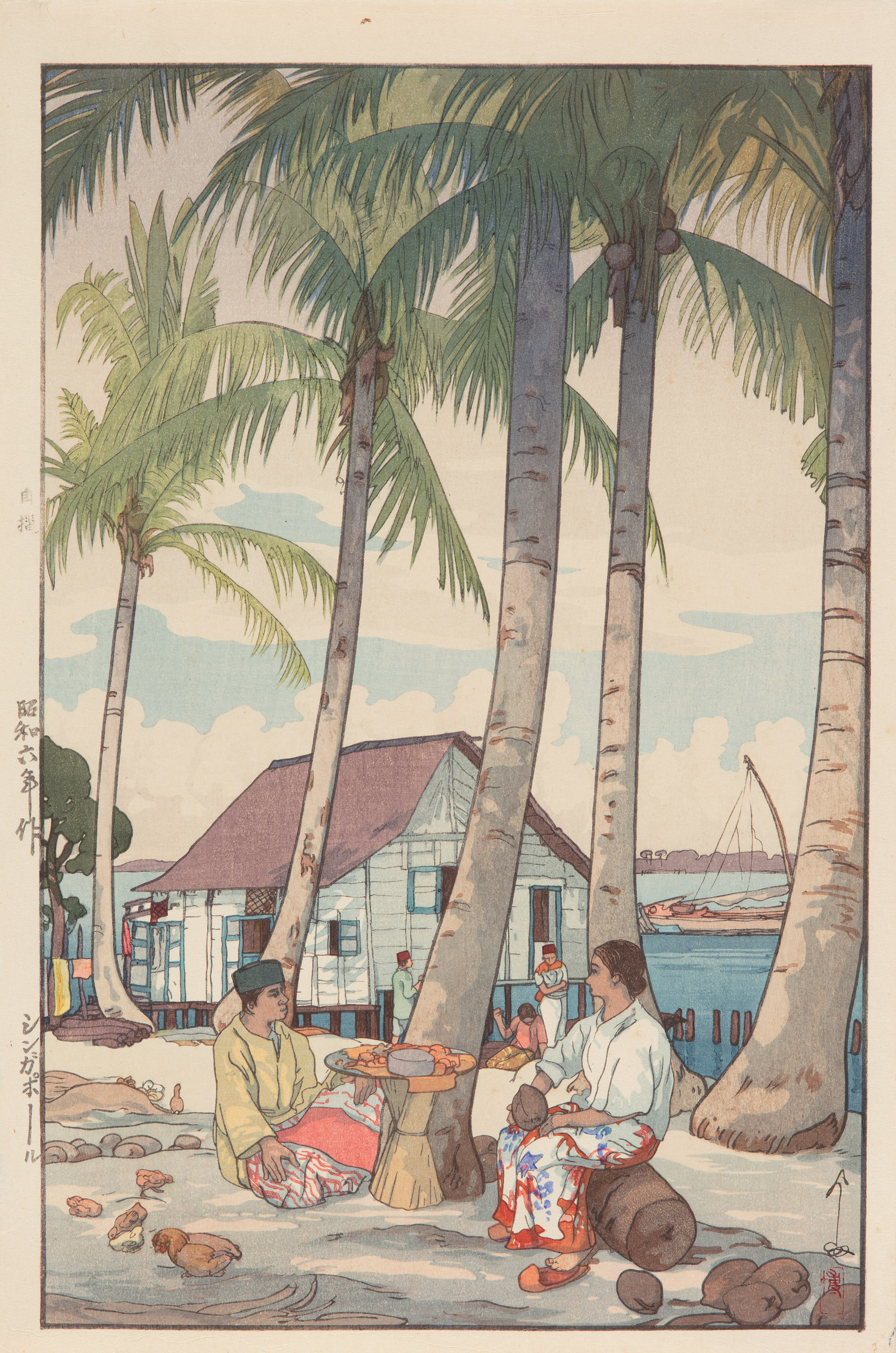

Yoshida Hiroshi

Kerala

Kokka woodblock print on paper, 9.7 X 14.7 in.

Collection: DAG

Hiroshi's artistic style was heavily influenced by Western techniques, which he incorporated into the traditional Japanese woodblock printing process. His mastery of the medium allowed him to create prints of remarkable detail and depth, capturing the beauty and essence of his subjects with precision and elegance. Dorothy Blair calls him a ‘progressive experimenter’, and shows how he sought to create a synthesis between Japanese and western artistic techniques: ‘He studied western methods; he traveled extensively in foreign countries; and he took from the west what seemed to him good for his own creative effort. Certainly his own wood-block prints profited in depth without losing the qualities of charm inherent in the wood-block process and without loss of the significant spirit of Japanese art.’ |

|

In the early twentieth century, Hiroshi embarked on a series of travels that would profoundly shape his artistic vision. Among his journeys, Hiroshi visited India (in 1930), where he was captivated by the country's rich culture, vibrant landscapes, and spiritual traditions. His experiences in India inspired a series of woodblock prints that would become some of his most celebrated works. |

|

|

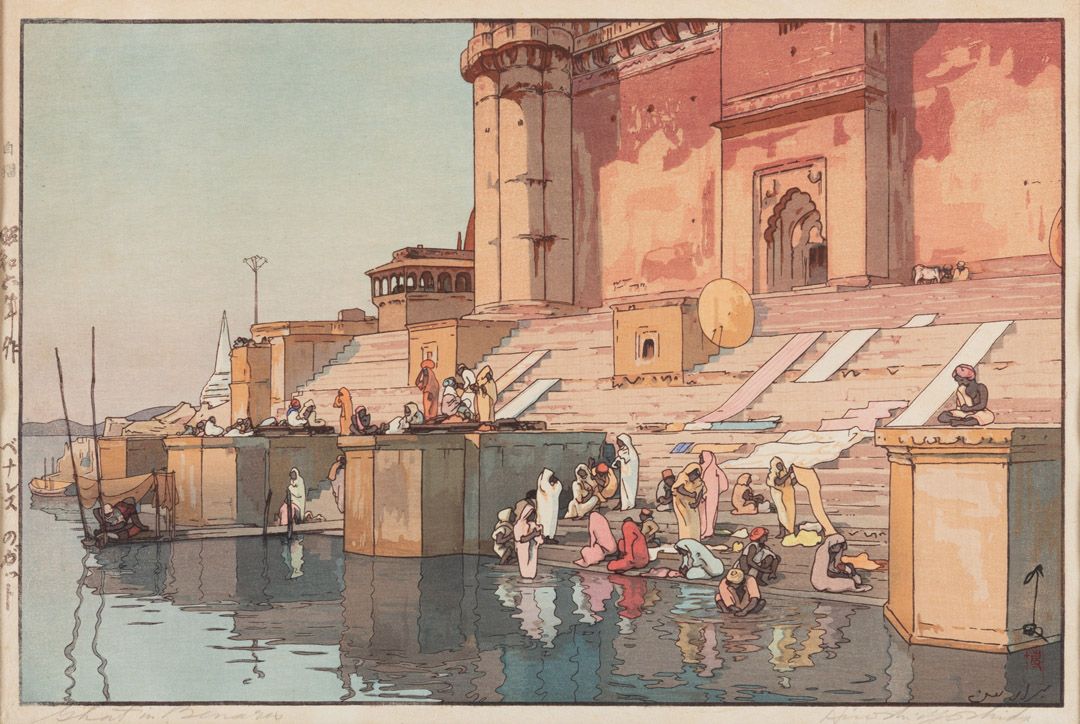

Yoshida Hiroshi

Ghat in Benaras (Benaresu No Gatto)

1931, Kokka woodblock print on paper, 9.5 x 14.5 in.

Collection: DAG

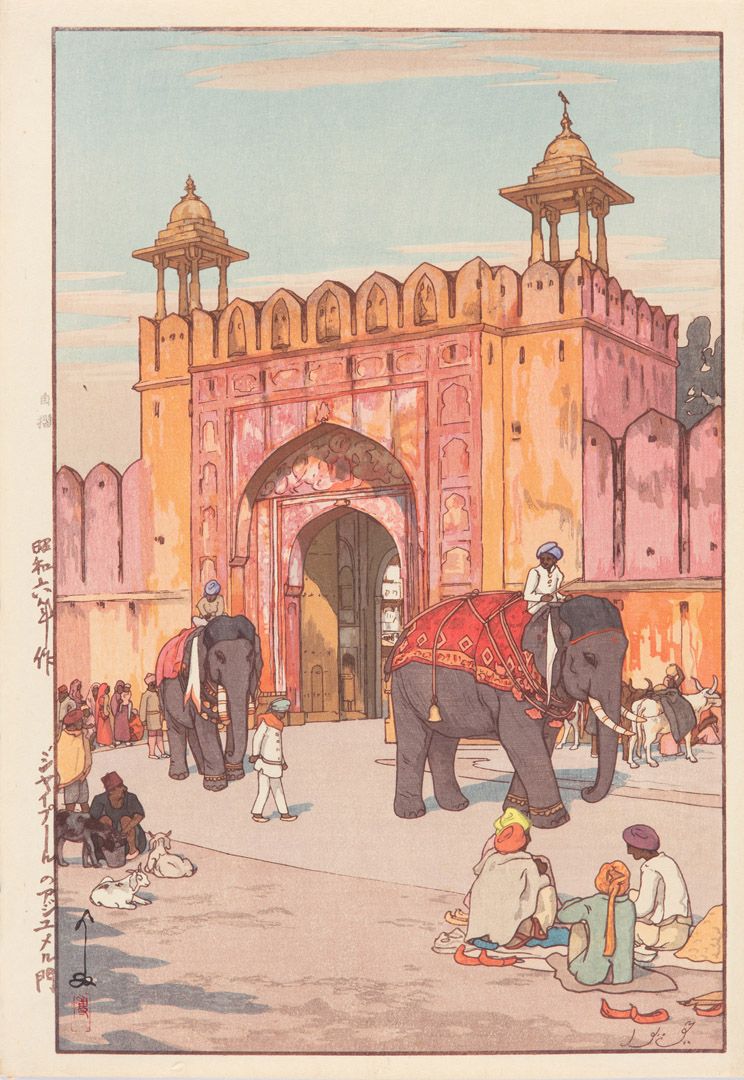

Yoshida Hiroshi

Ajmer Gate (Jaipuuru No Ajumeru Mon)

1931, Kokka woodblock print on paper, 14.7 x 9.7 in.

Collection: DAG

Hiroshi's Indian prints depict a wide range of subjects, from majestic Himalayan peaks to bustling city streets and serene rural landscapes. He had a keen eye for capturing the intricate architectural details of India's temples, palaces, and monuments, as well as the everyday life of its people. Through his prints, Hiroshi conveyed a sense of reverence for the spiritual and cultural heritage of India, portraying its landscapes and landmarks with a sense of awe and admiration. One of Hiroshi's most famous Indian prints is Benares, depicting the sacred city (now Varanasi) on the banks of the Ganges River. In this print, Hiroshi masterfully captures a regular scene at its famous ghats. The play of light and shadow adds depth and atmosphere to the scene, imbuing it with a sense of mystery and spirituality. |

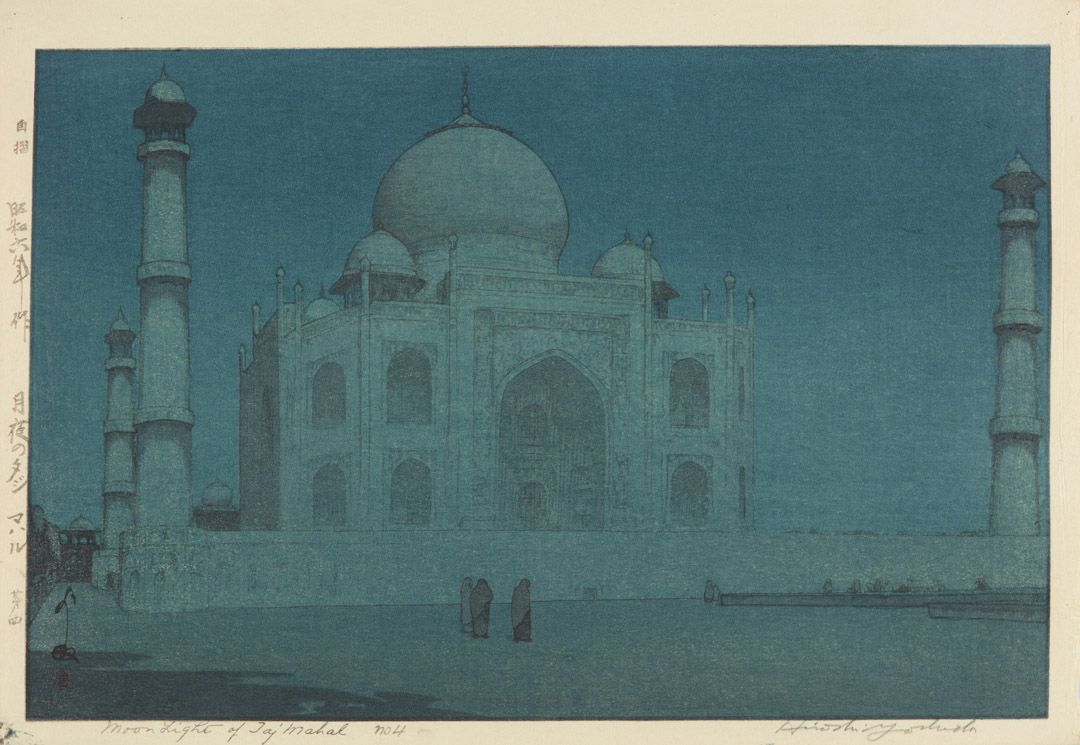

Yoshida Hiroshi

Taj Mahal Under the Moonlight (Tsukiyo No Taji Maharu)

Collection: DAG

Another notable work is Taj Mahal Under the Moonlight, showcasing the iconic mausoleum in Agra, India. Hiroshi's rendition of the Taj Mahal is both majestic and intimate, conveying the monument's grandeur while also capturing its exquisite architectural details and serene beauty, under the romantic glow of moonlight. |