|

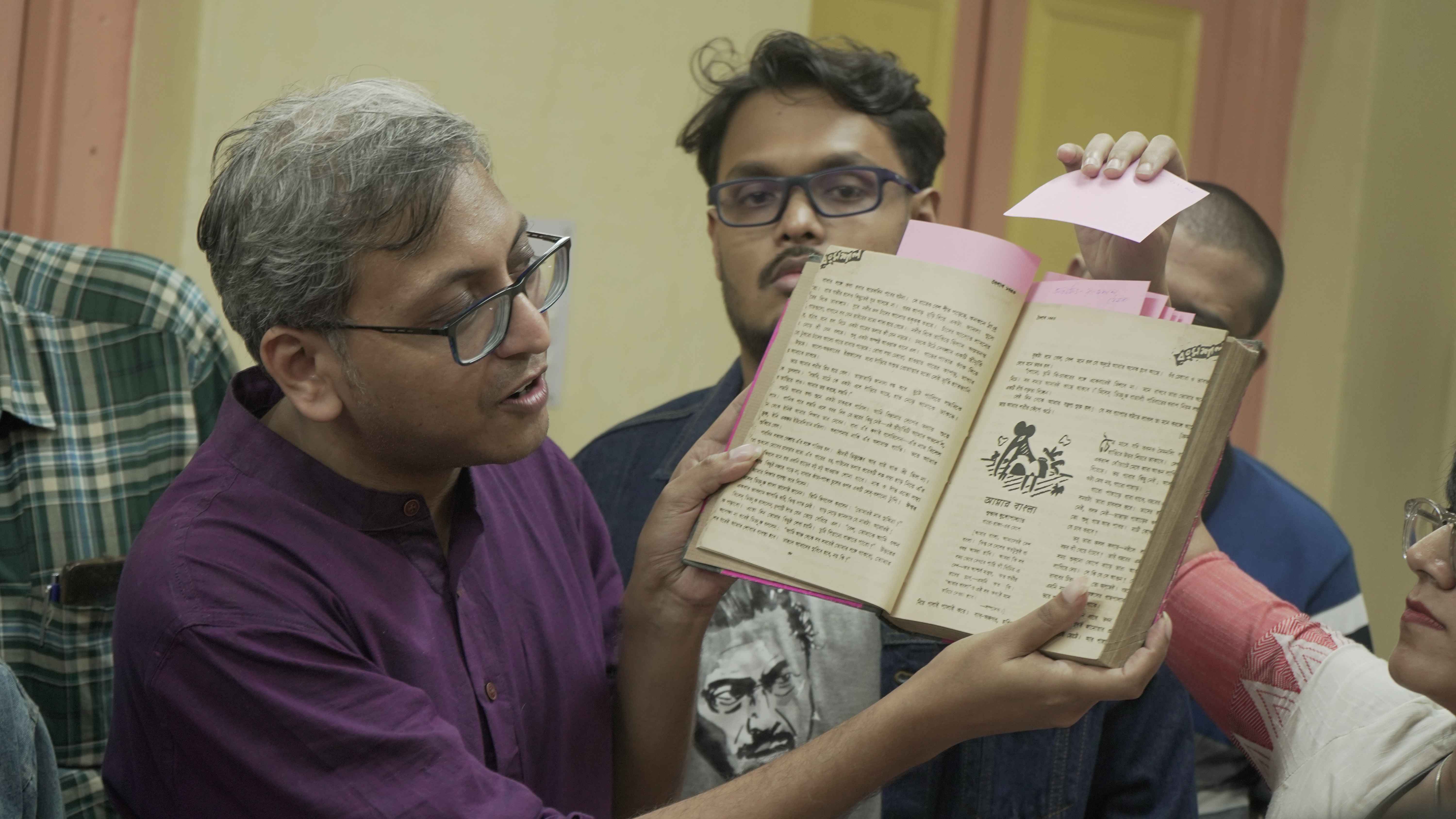

Travel With Us ART IN PRINT: VIEWING PERIODICALS AT THE UTTARPARA LIBRARYAmreeta Das February 01, 2023 Have you wondered how people looked at paintings and photographs in the nineteenth century? For DAG’s annual heritage festival ‘The City as a Museum’, we explored various aspects of the city’s visual culture. As we are about to launch the DAG Journal let us revisit the walk co-led by Sarbajit Mitra and Amreeta Das at the Uttarpara Jaykrishna Public Library to delve into the periodical archive and trace the evolution of printed pictures in India. Flipping through the pages of these periodicals offered glimpses into the everyday habits of consuming art—from simple wood-cut and lithograph illustrations, to full plate colour reproductions of paintings and photographs, artist albums, and exquisitely ornate typography. |

|

THE WORLD AT OUR DOORSTEP: THE RISE OF PERIODICALS As free circulating libraries proliferated outside the main urban centres, readers could access the latest developments across disciplines—from archaeology, astronomy, medicine, history and literature to scientific inventions. The library at Uttarpara, set up by Jaykrishna Mukhopadhyay—a modernizing Zamindar who transformed a backward village into an important cultural centre—is regarded as one of the oldest free circulating public libraries. Mukhopadhyay subscribed to all the leading periodicals of his time, a format which facilitated hitherto unprecedented channels of communication. Due to its serialized nature people could engage in sustained debates and disputations through letters and critical essays, and actively participate in shaping public opinion. |

|

|

Edward Lear

Illustration for a translated poem

Rangmashal (August 1946)

Edward Lear

Illustration for a translated poem

Rangmashal (October 1946)

Headpiece

Rangmashal (April 1946)

Some of these periodicals began to carry illustrations from the middle decades of the nineteenth century. There was a concerted attempt by cultural and educational reformers to make the text more accessible and communicable. Illustrations served this unique purpose. People could now imagine the places, things and creatures they read about. |

|

THE WORLD IN PICTURES: EARLY ATTEMPTS The first ever Bengali illustrated book, Bharat Chandra Ray's Annadamangal (1816) was published by Gangakishore Bhattacharya. Six years later, John Lawson, a missionary who turned up in India to work at the Baptist Mission of Serampore, brought out a remarkable series—Pashwabali or Animal Biography in 1822, hailed as the first illustrated periodical in the Bengali language. While Ramchaund Roy’s woodblock illustrations of Annadamangal closely followed the visual language of Bengali almanacs, Lawson's illustrated Animal Biography, was closer to the realist images that would populate illustrated periodicals from 1850s onwards. |

|

Image Credit: The British Library, Public Domain |

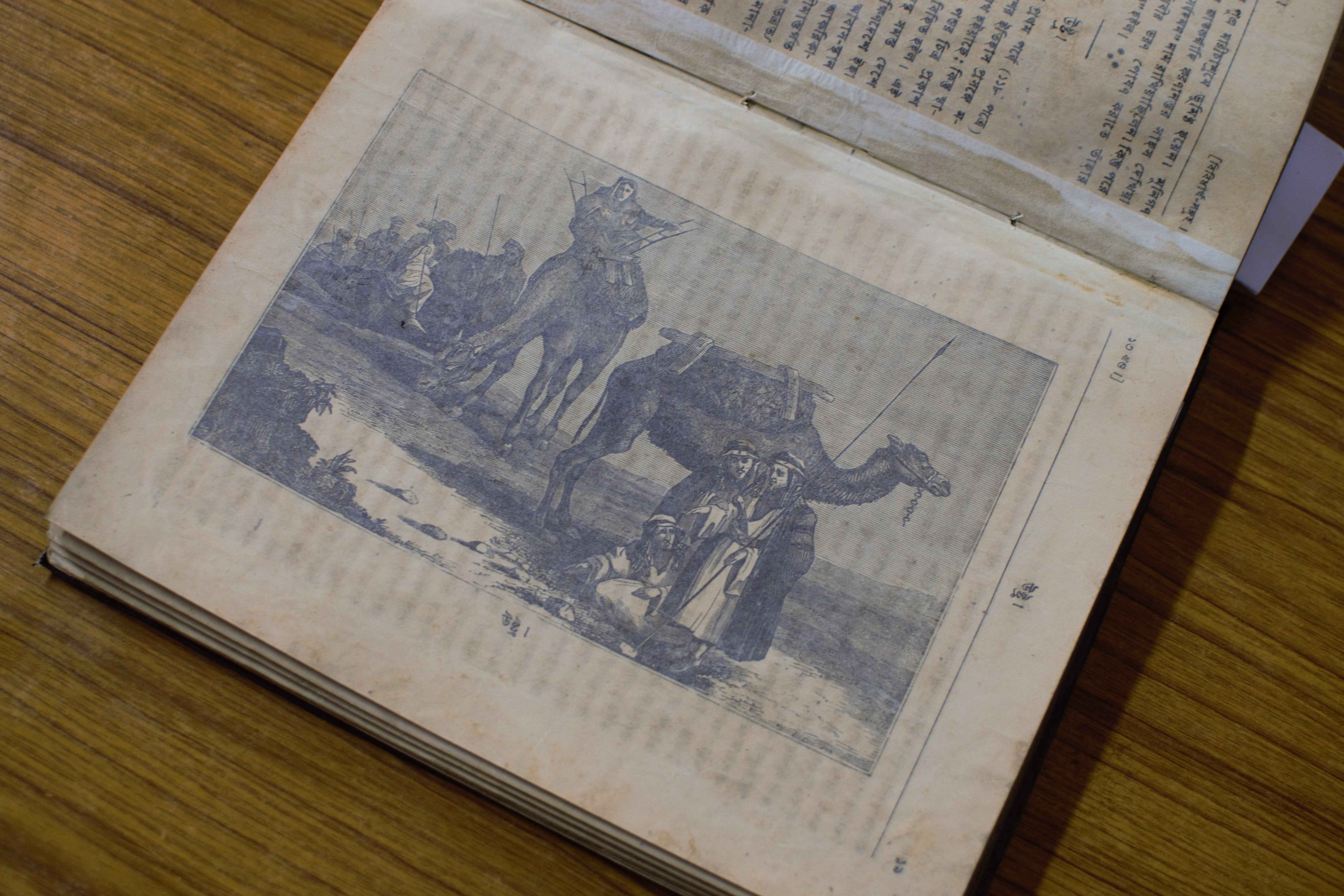

Anonymous

Ushtha (Camels)

Bibidartha Sangraha (December, 1851)

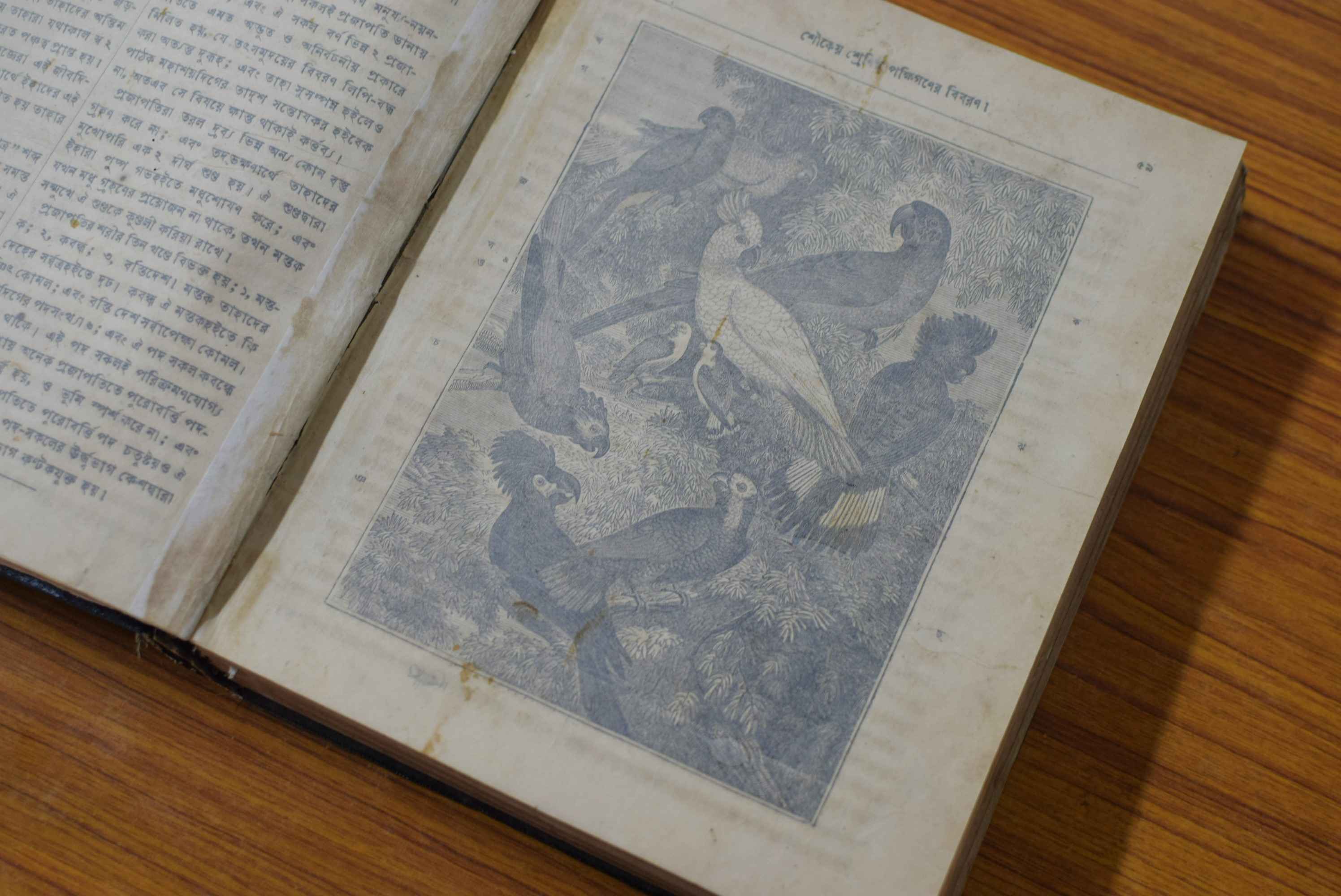

Anonymous

Soukeya Srenir Pokkhigoner Bibaran (Description of Birds from the Popinjay family)

Bibidartha Sangraha (December, 1851)

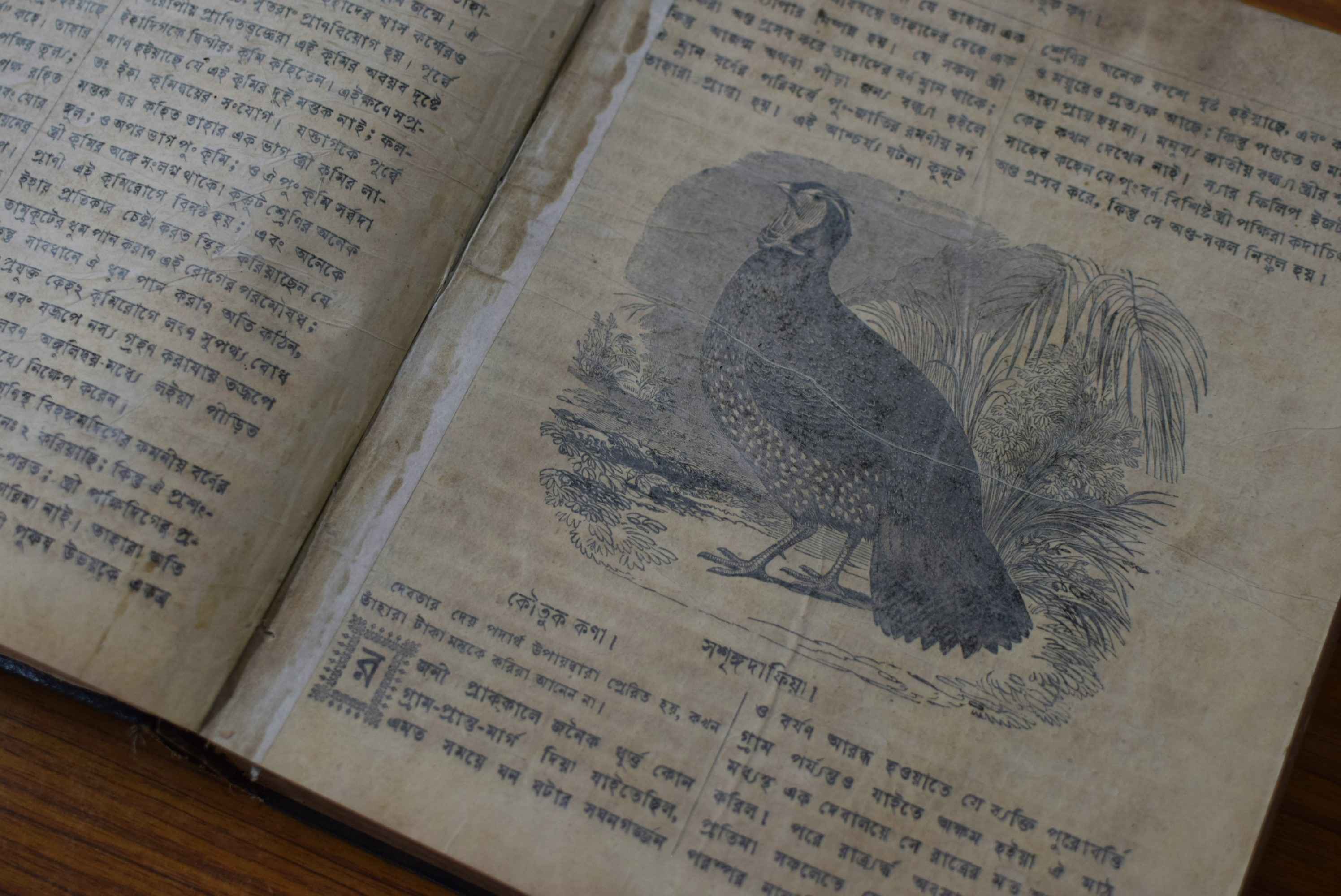

Anonymous

Shawsringadafiya

Bibidartha Sangraha (December, 1851)

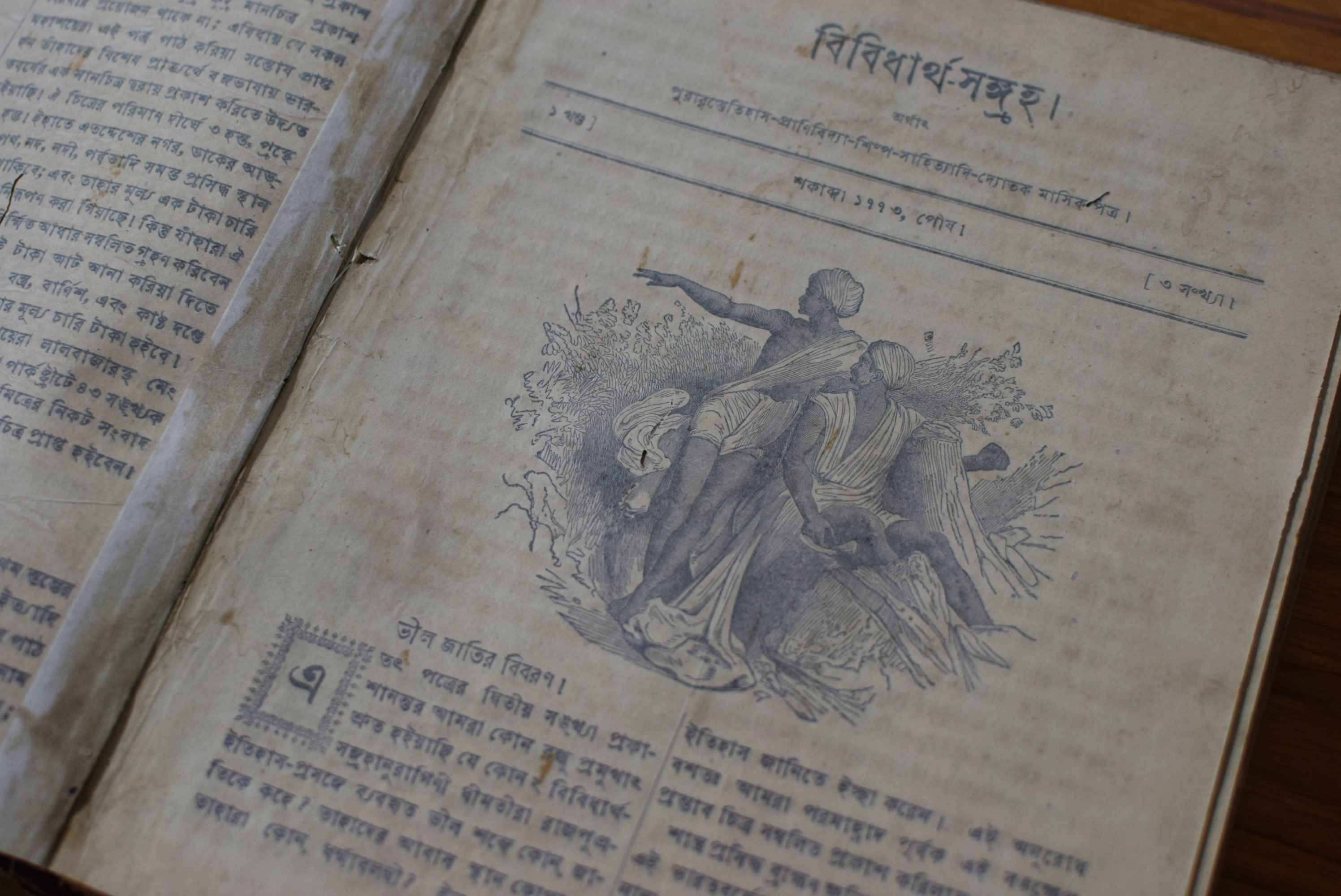

Anonymous

Bhil Jatir Bibaran (Description of the Bheel Community)

Bibidartha Sangraha (December, 1851)

In the library’s collection we found Bibidartha Sangraha, a popular general knowledge periodical published by an organization that was founded by Mukhopadhyay—the Calcutta Vernacular Literature Society. This periodical was adapted from the Victorian penny magazine format, carrying instructive essays on history, nature and science, with full-plate illustrations of exotic animals and birds, people and places—printed with woodcuts imported from England. Within two decades of the first appearance of Pashwabali, the nature of illustrations in Bibidartha Sangraha singals a maturing taste for more detailed printed pictures. |

|

LESSONS IN LOOKING: BUILDING A TASTE IN FINE ART The market for illustrated periodicals rapidly expanded and editor-entrepreneurs like Ramananda Chattopadhyay realized the educational potential of printed pictures. Prabashi was born out of a unique pedagogic spirit—to build a popular taste in fine art. Following in Prabashi’s footsteps, a number of other periodicals—like Bichitra and Masik Basumati—began reproducing full-page colour plates of leading artists. Crucial to this rapid spread of colour reproductions was print-maker and illustrator par excellence Satyajit Ray's grandfather Upendrakishore Ray Chowdhury, whose printing press U. Ray and Sons produced the illustrations for Prabashi. Moving from sepia monotones and monochrome half-tone blocks, to three-tone colour blocks, Prabashi printed over 200 pictures and plates over a single year. |

|

|

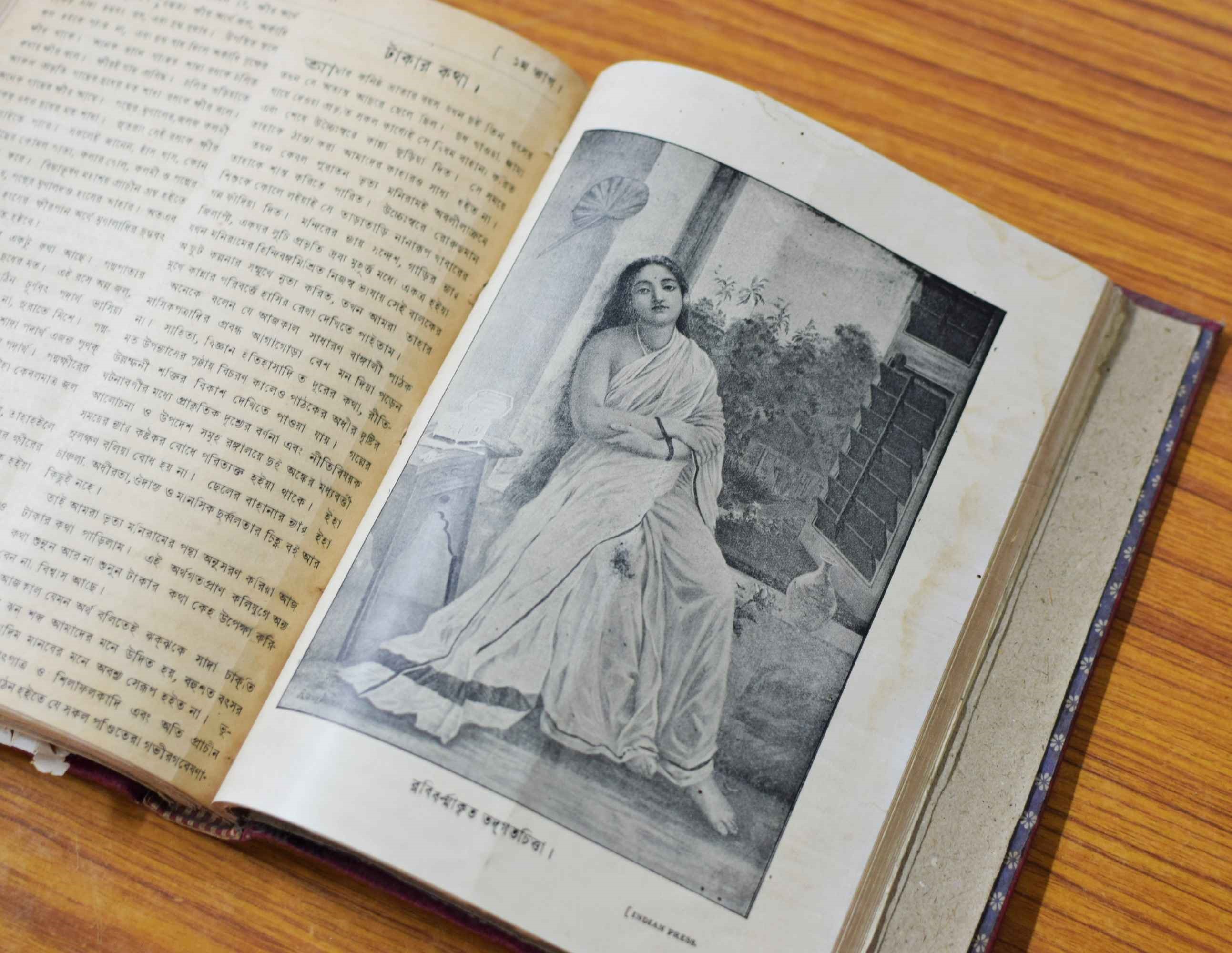

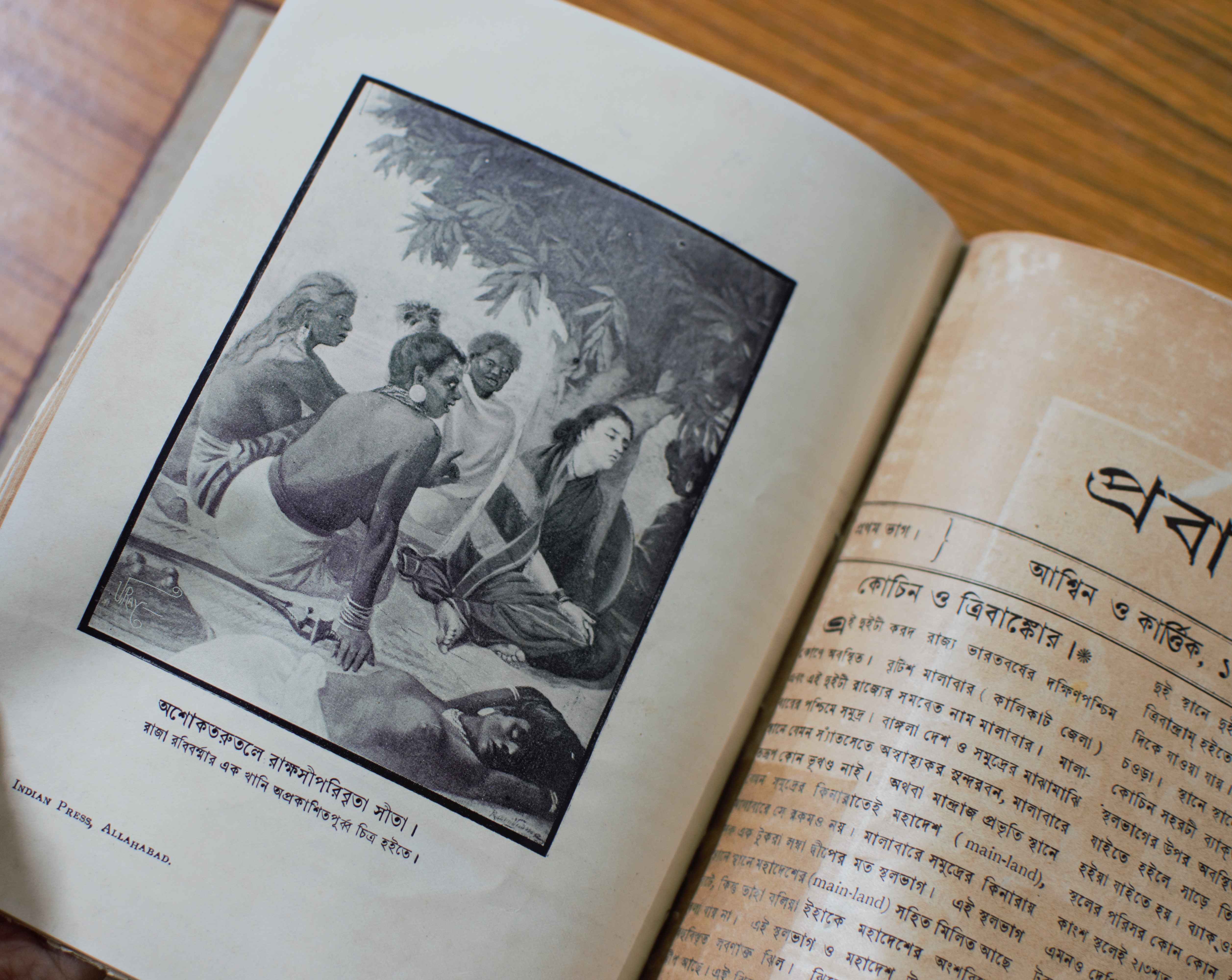

Raja Ravi Varma

Ravi Varma's Woman lost in thoughts

Prabashi (May 1906)

Raja Ravi Varma

Sita surrounded by demonesses under the Ashok tree, excerpted from Raja Ravi Varma’s unpublished image

Prabashi (April 1901)

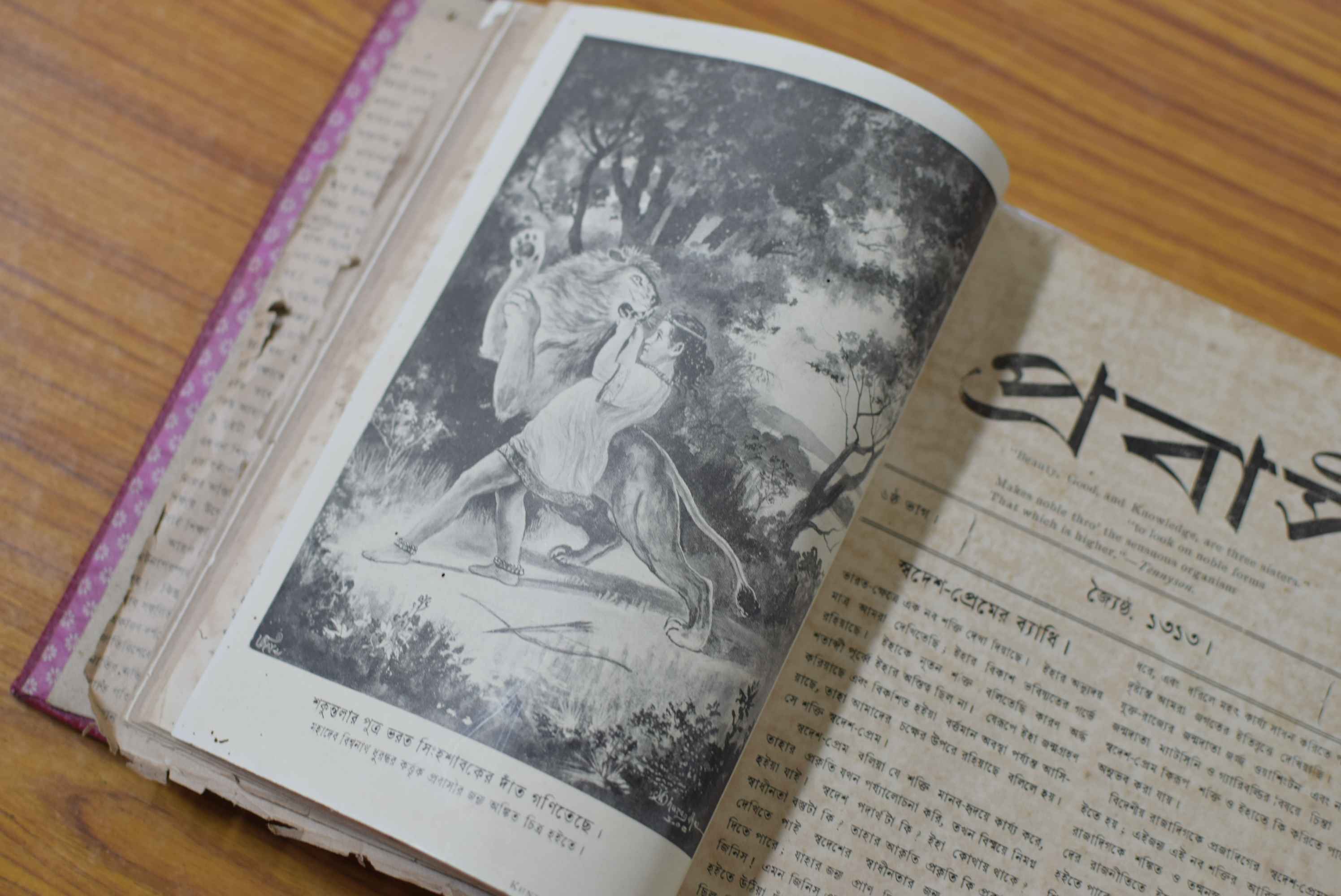

M. V. Dhurandhar

Sakuntala's son Bharat counting a lion's teeth

Prabashi (May 1906)

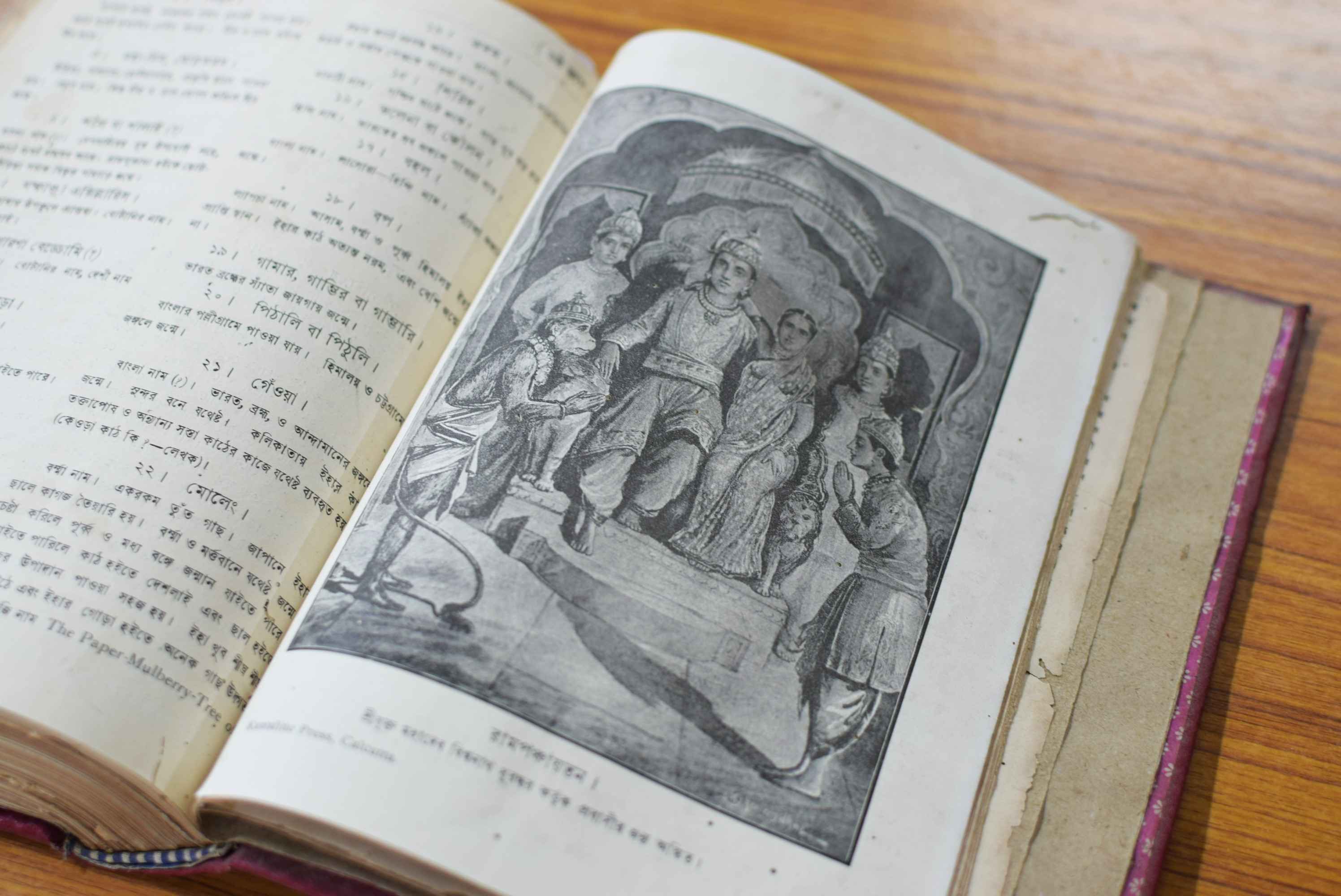

M. V. Dhurandhar

Ram’s Panchayat

Prabashi (March 1907)

The first few issues of Prabashi were entirely devoted to academic artists like Raja Ravi Varma, M. V. Dhurandhar and Bamapada Bannerjee. Though Ravi Varma was well established as a commercial artist—his works were on advertisements, calendars and other popular media, outside the realm of ‘fine art’—his iconography of Hindu deities was regarded as an improvement upon the cheap, garishly coloured chromolithographs published by popular art studios like Calcutta Art Studio. Ramananda Chattopadhyay reproduced almost all the famous Ravi Varma paintings to wean people away from ‘crude religious prints’. Some issues also contained paintings by the famous Bombay artist M.V. Dhurandhar, solely produced for the purpose of printing in Prabashi. |

|

NEW VOCABULARIES: THE RISE OF NATIONALIST ART The Swadeshi Movement, and the attempt by a group of artists in Calcutta to develop a new Pan-Asian language of art—popularly known as Bengal School—spawned a new kind of visual activism in contemporary periodicals. Prabashi began featuring artists like Abanindranath Tagore and Nandalal Bose, and its essays criticised academic realists like Ravi Varma for failing to live up to the new spirit of nationalist fervour. This conscious taste-making project, led by the likes of Chattopadhyay, attempted to shape an integrated sensibility in its readers—the periodicals contained illustrated articles on a variety of topics like travelogues with photographs, articles on global politics, literary criticism, poems and serialized novels, photographs and art criticism, among others, so that people could acquire an indigenous visual and literary vocabulary. |

|

|

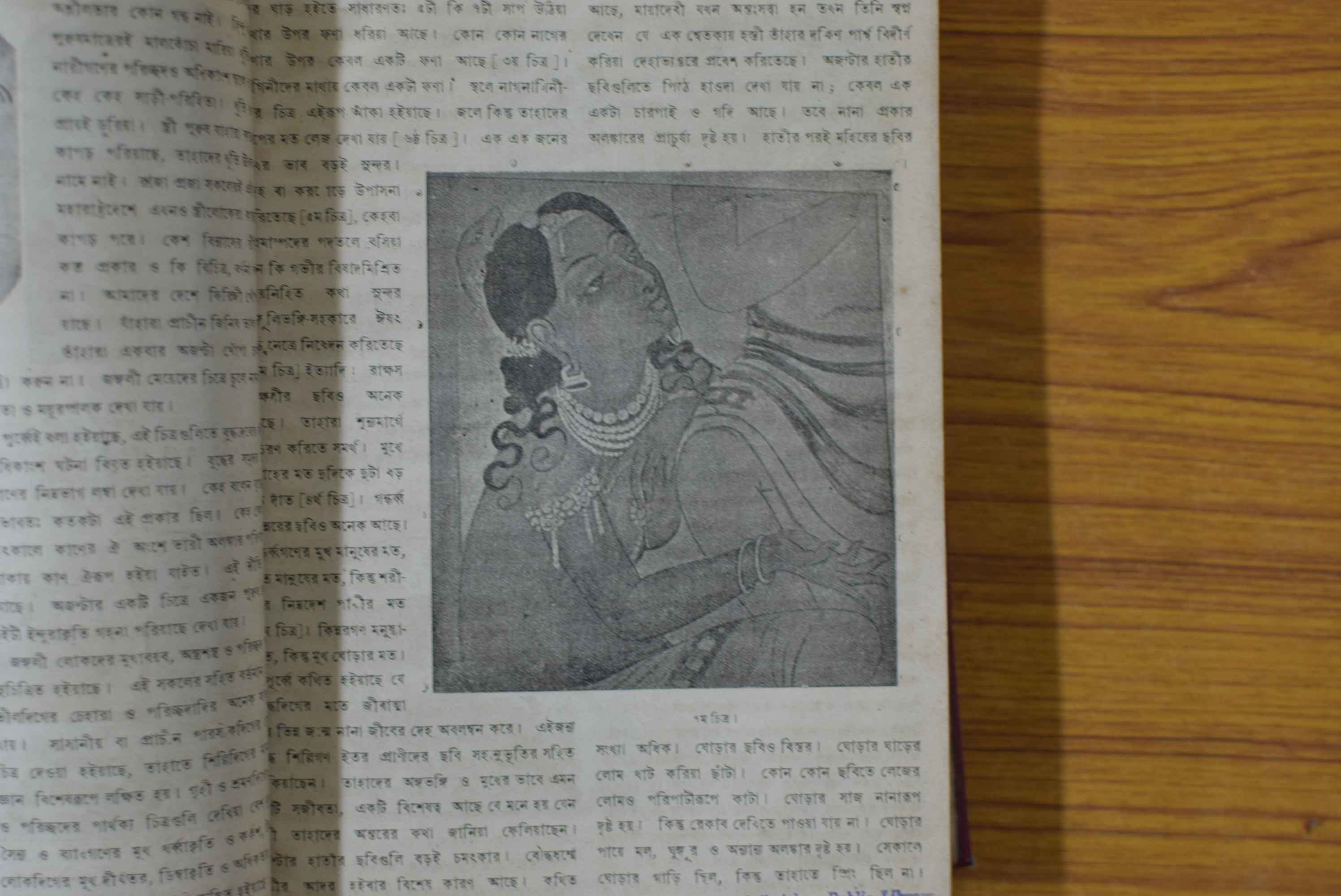

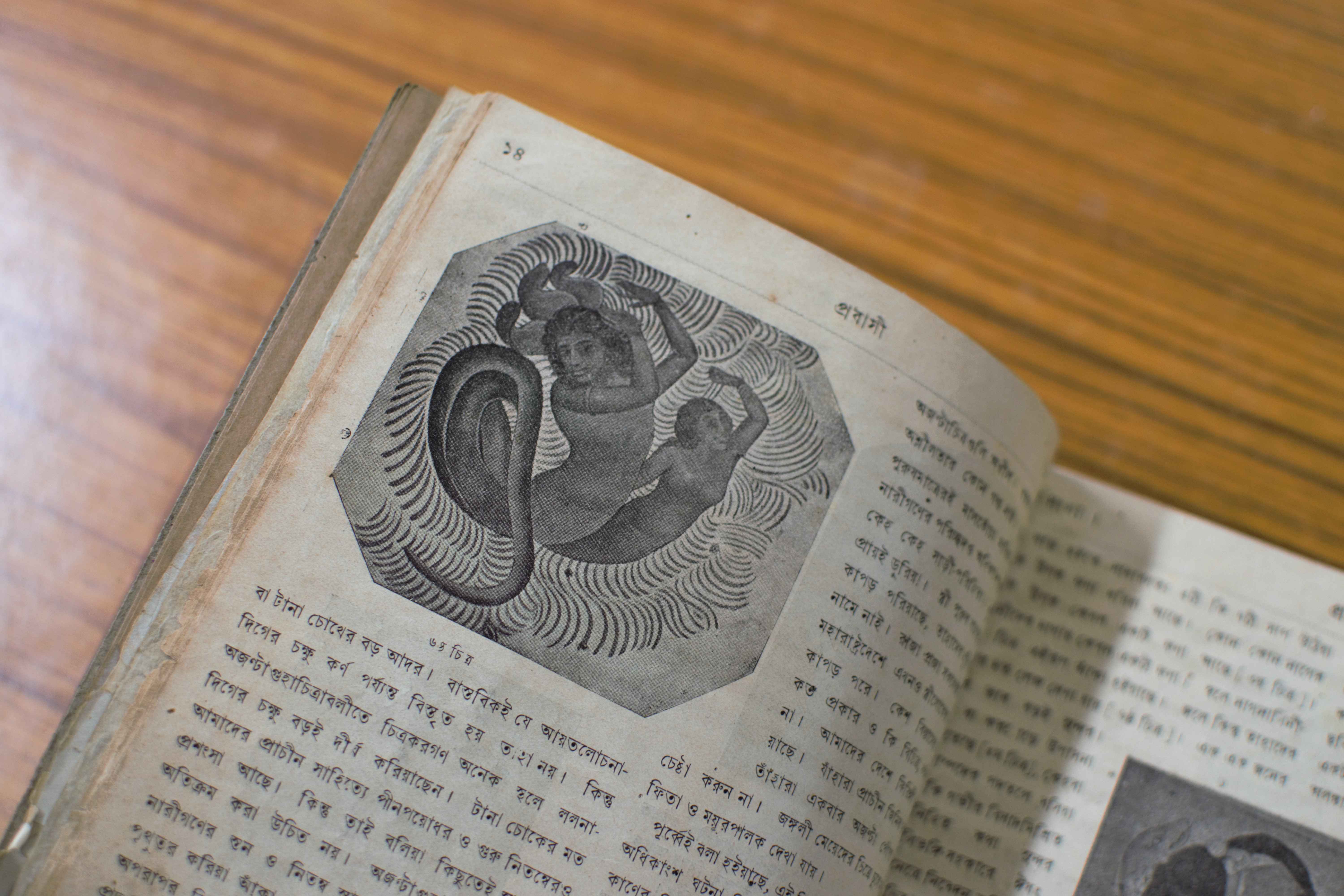

Anonymous

Ajanta Guhachitrabali (The cave paintings of Ajanta)

Prabashi (April 1901)

Anonymous

Ajanta Guhachitrabali (The cave paintings of Ajanta)

Prabashi (April 1901)

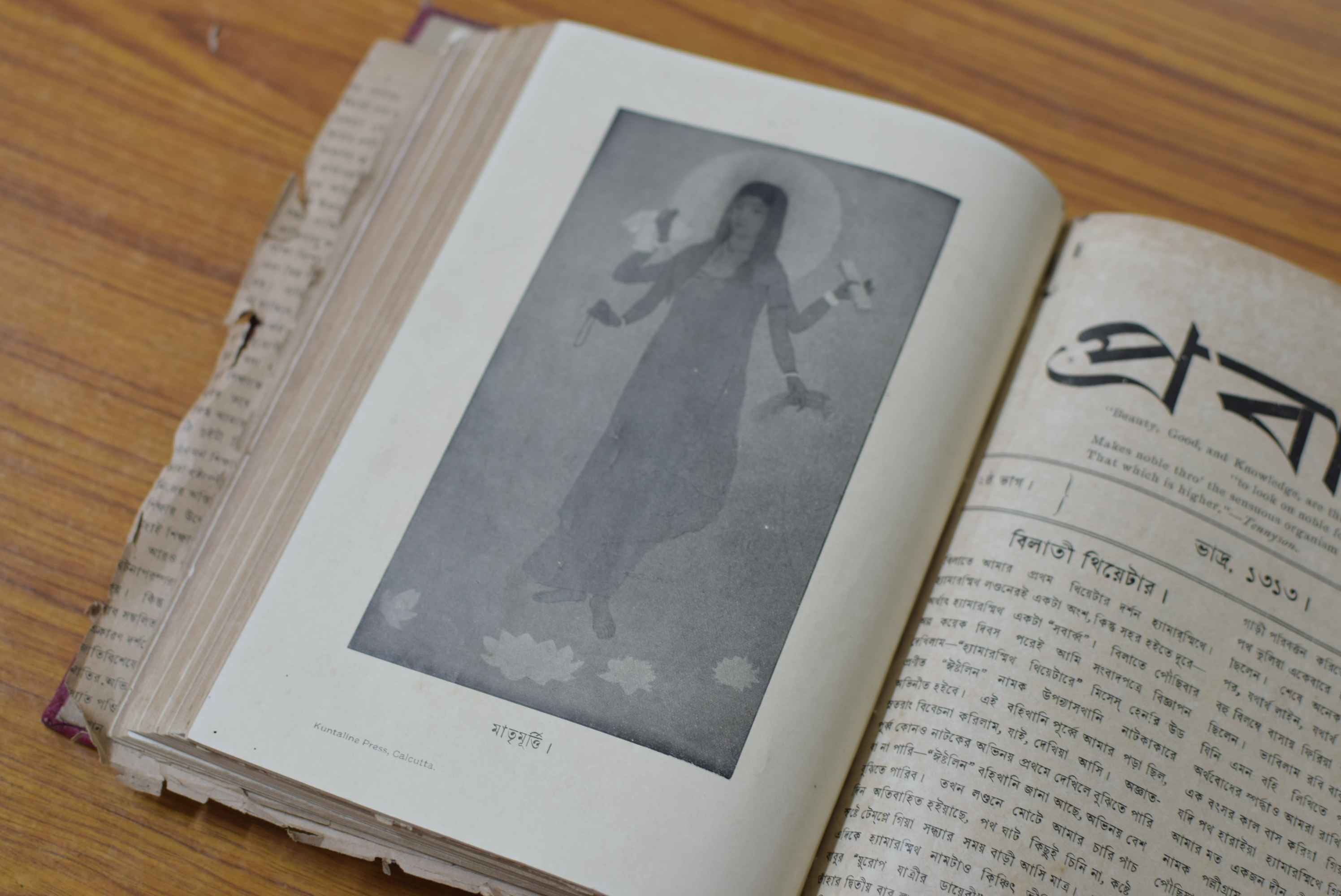

Abanindranath Tagore

Matrimurti (The Figure of the Mother)

Prabashi (August 1906)

Even before Prabashi’s conscious shift towards the Bengal School, its very first 1901 issue anticipates emerging artistic developments. It features a detailed account of the cave paintings of Ajanta and Ellora with rich illustrations. The iconography of the Ajanta paintings played a very crucial role in shaping the sensibility of Abanindranath Tagore and his students. Five years later, the August 1906 issue carried a full-page illustration of Abanindranath Tagore’s painting of the new Swadeshi icon—titled simply ‘Matrimurti’—and Sister Nivedita’s entry on the work, which identified it as ‘Bharat Mata’ for the first time. |

|

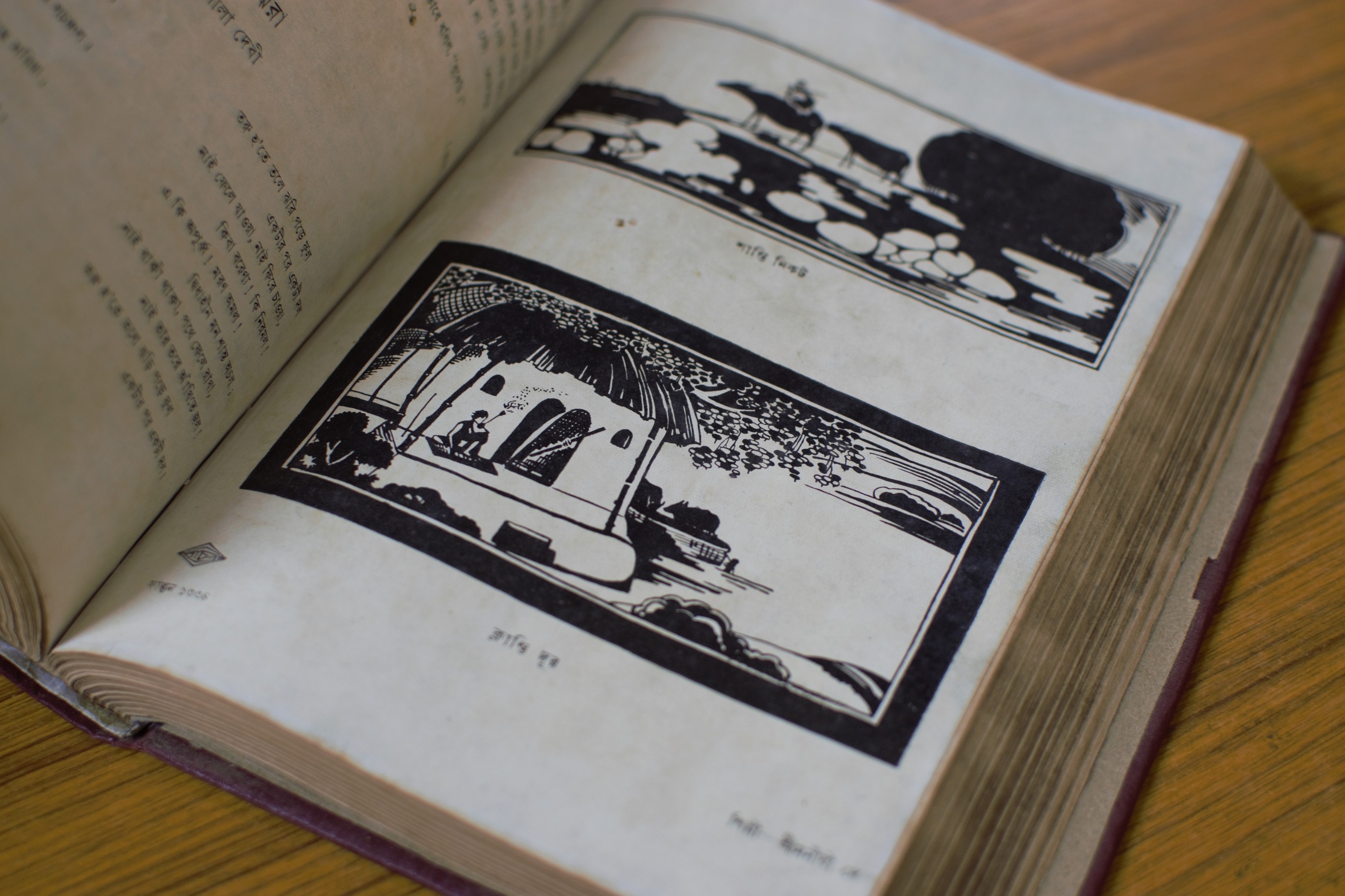

BICHITRA: A NEW WONDER OF DESIGN Bichitra, published from 1927 onwards and edited by Upendranath Gangopadhyay, spawned new formats—like the picture album, which functioned like the modern photo essay. Illustrations, reproductions, typography—non-textual elements—are used in a more conscious manner to construct narratives. Such storytelling techniques were meant for readers whose sensibilities were being shaped by new visual media like early cinema. |

|

|

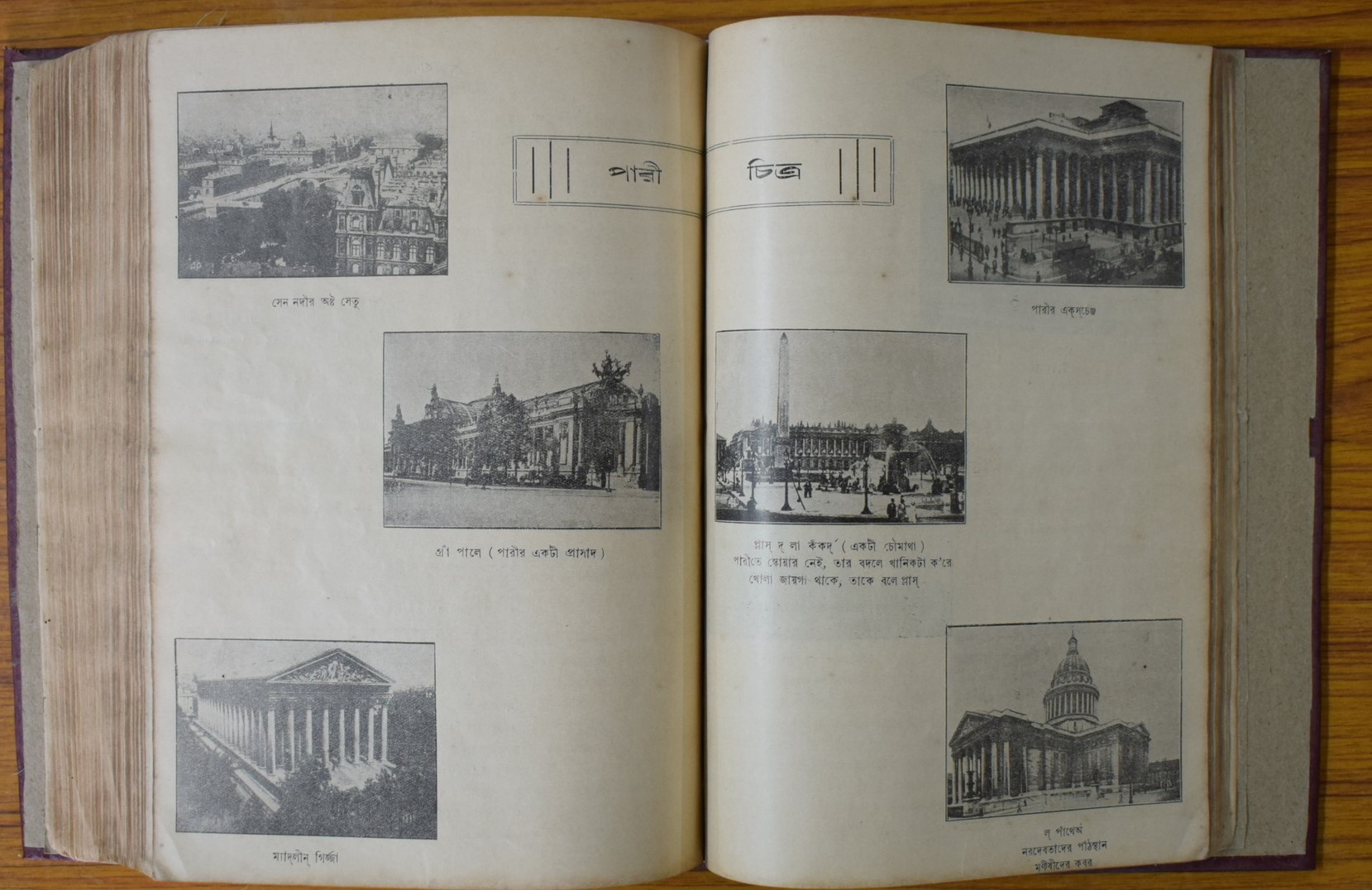

Pari Chitra (An album of Paris)

Bichitra (May 1928)

Asit Kumar Halder

Sketches

Bichitra (May 1928)

Manishi Dey

Peace Here, Exhaustion Gone

Bichitra (February 1928)

Sudhanshukumar Ray

Chitra-Bichitra

Bichitra (January 1928)

Sudhanshukumar Ray

Chitra-Bichitra

Bichitra (January, 1928)

Bichitra's unique contribution lay in introducing an image series. The first few issues primarily carry photographic albums of foreign lands, such as Paris, Switzerland and Spain. Then the albums start reproducing photographs of Greek sculptures and old European masters often following them up with reproductions of contemporary European modernists like Degas, Renoir and Matisse. From the third year of its publication, it began reproducing albums of Indian artists like Manishi Dey, Sudhanshu Ray, Sudhir Khastgir and Nandalal Bose, to name a few, creating a compendium of past and present art practitioners of India. Giving its readers a sense of European and indigenous art, Bichitra consciously creates a truly globalist timeline of art history. |

|

|

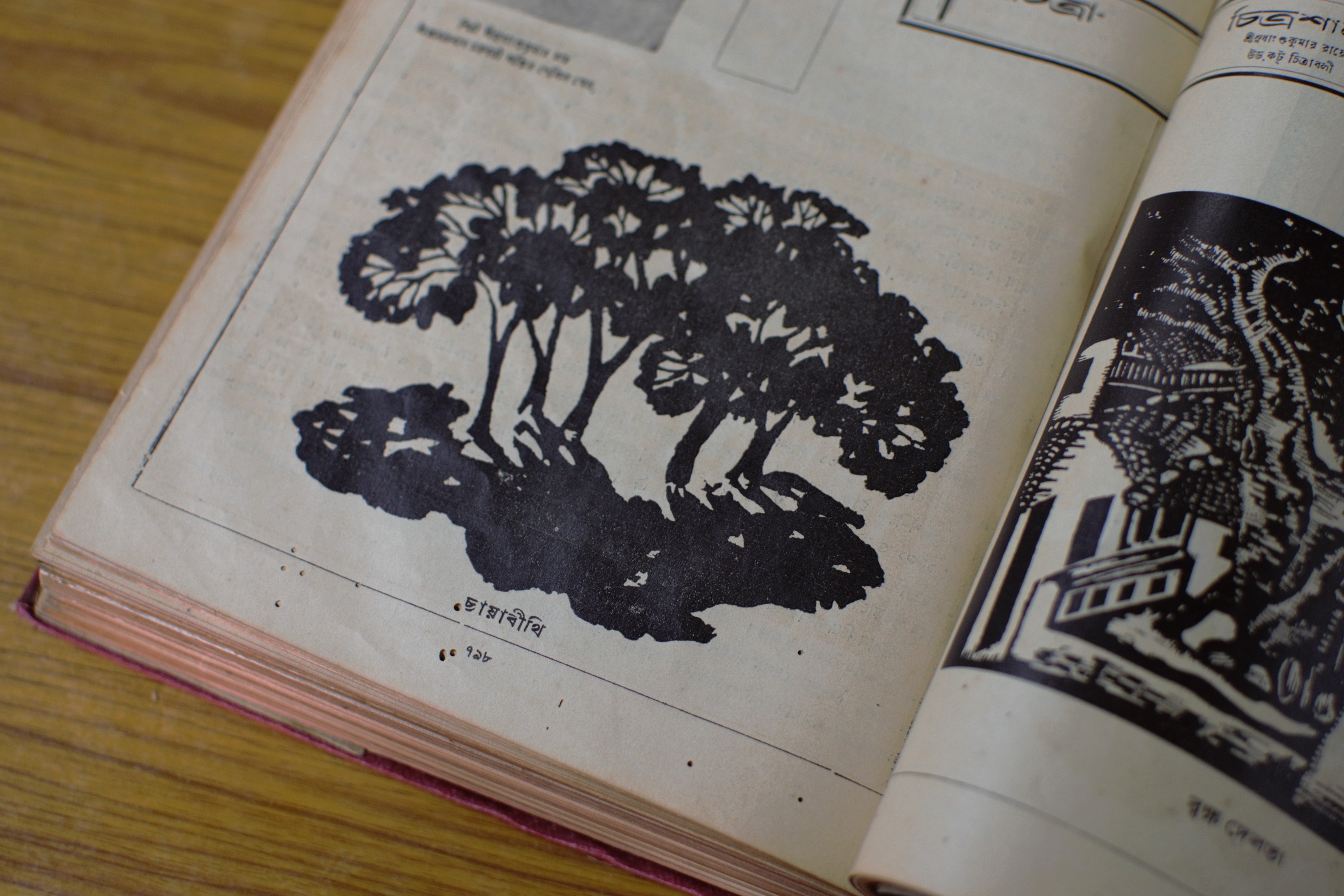

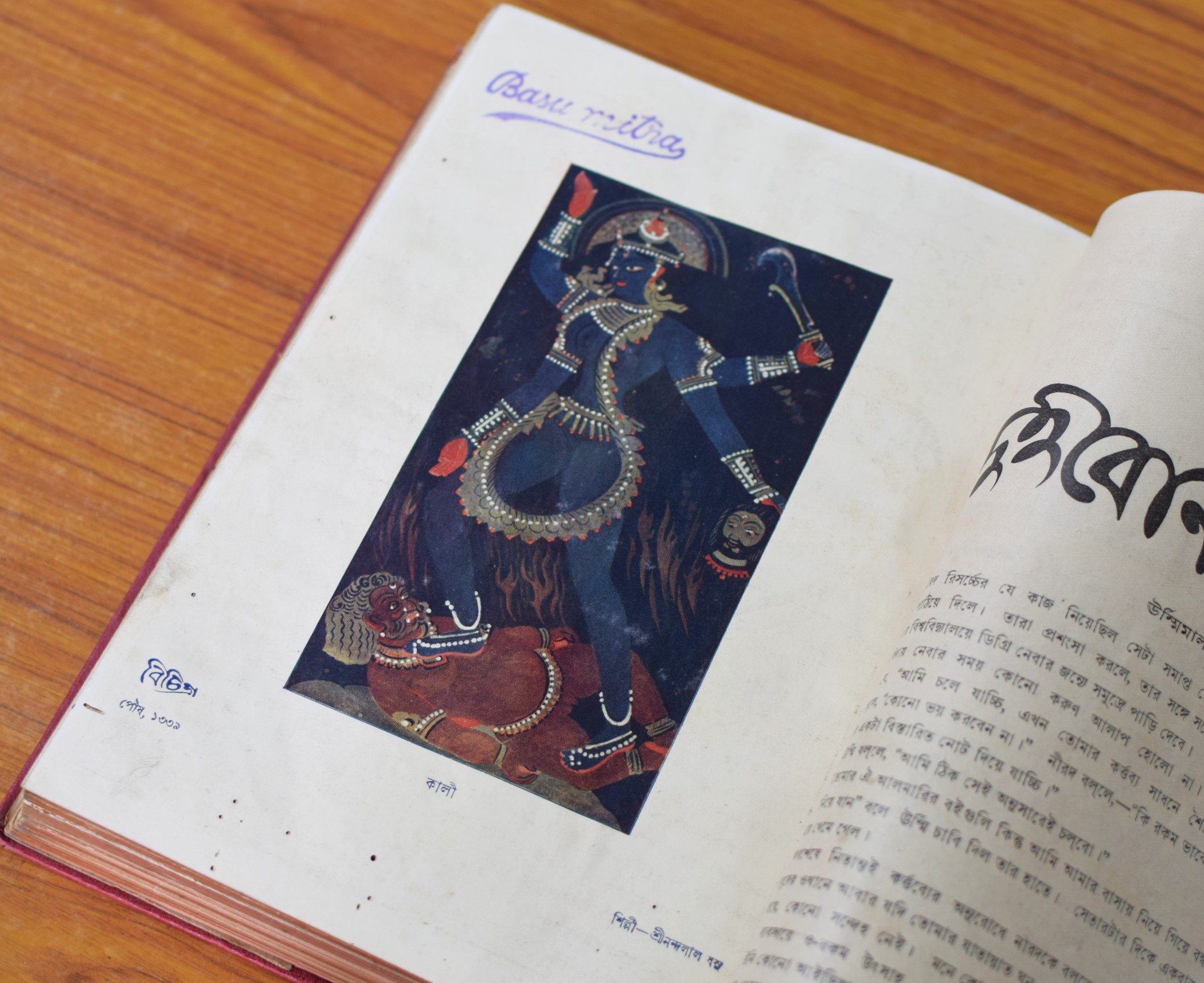

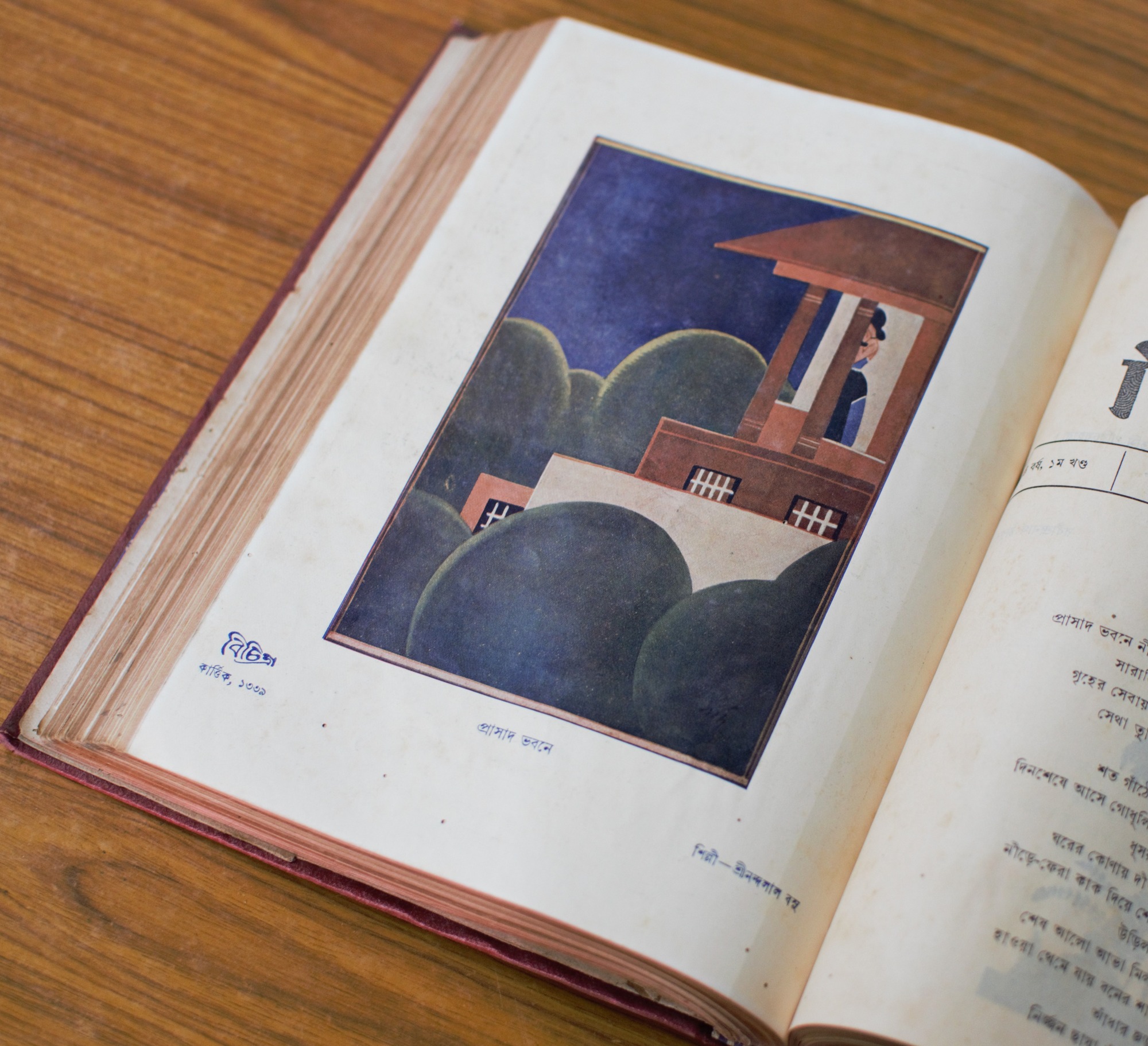

Nandalal Bose

Kali

Bichitra (January 1928)

Nandalal Bose

Prashad Bhabane (In the palace)

Bichitra (October 1932)

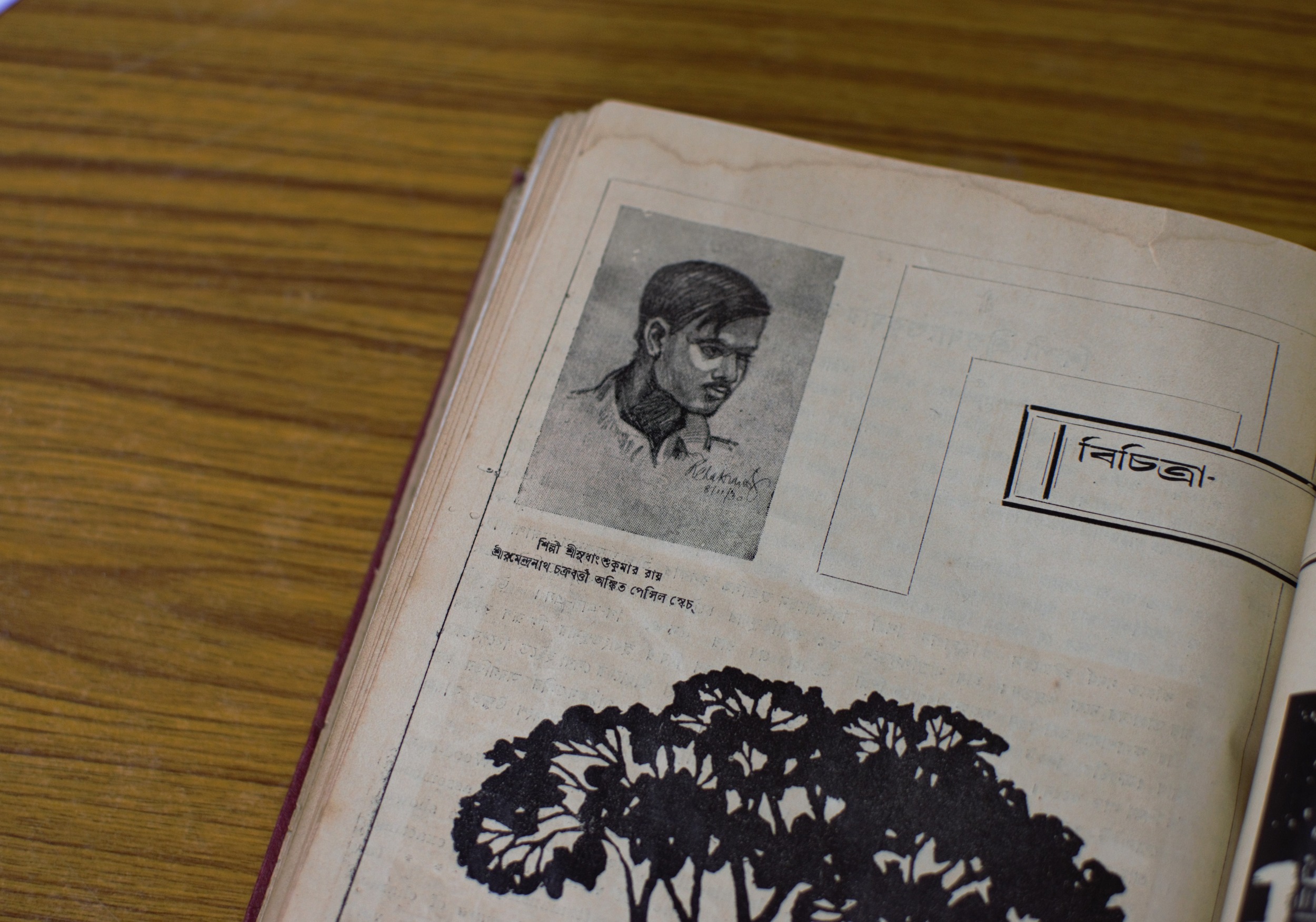

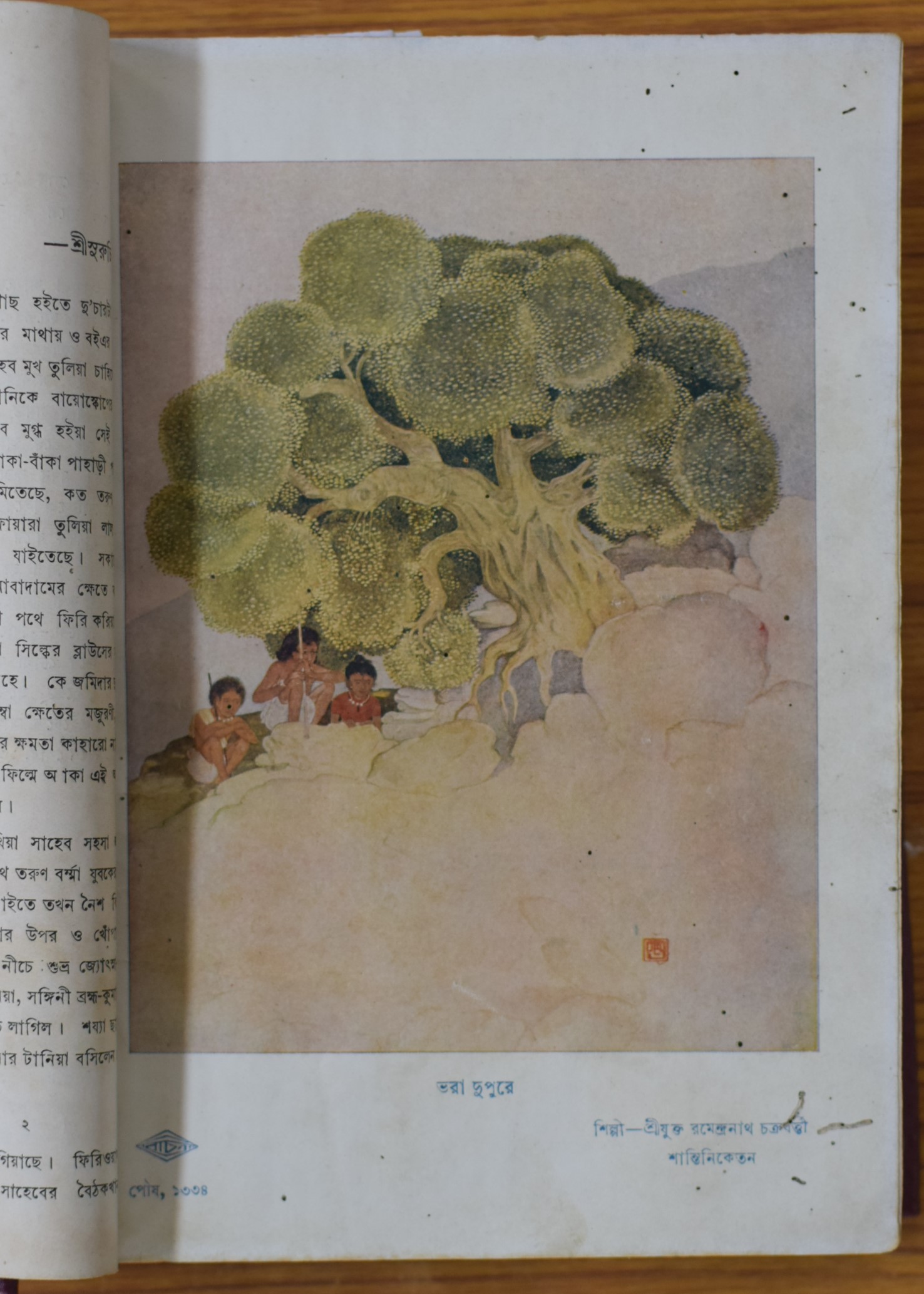

Ramendranath Chakravarty

Bhara Dupure (At Noon)

Bichitra (December 1927)

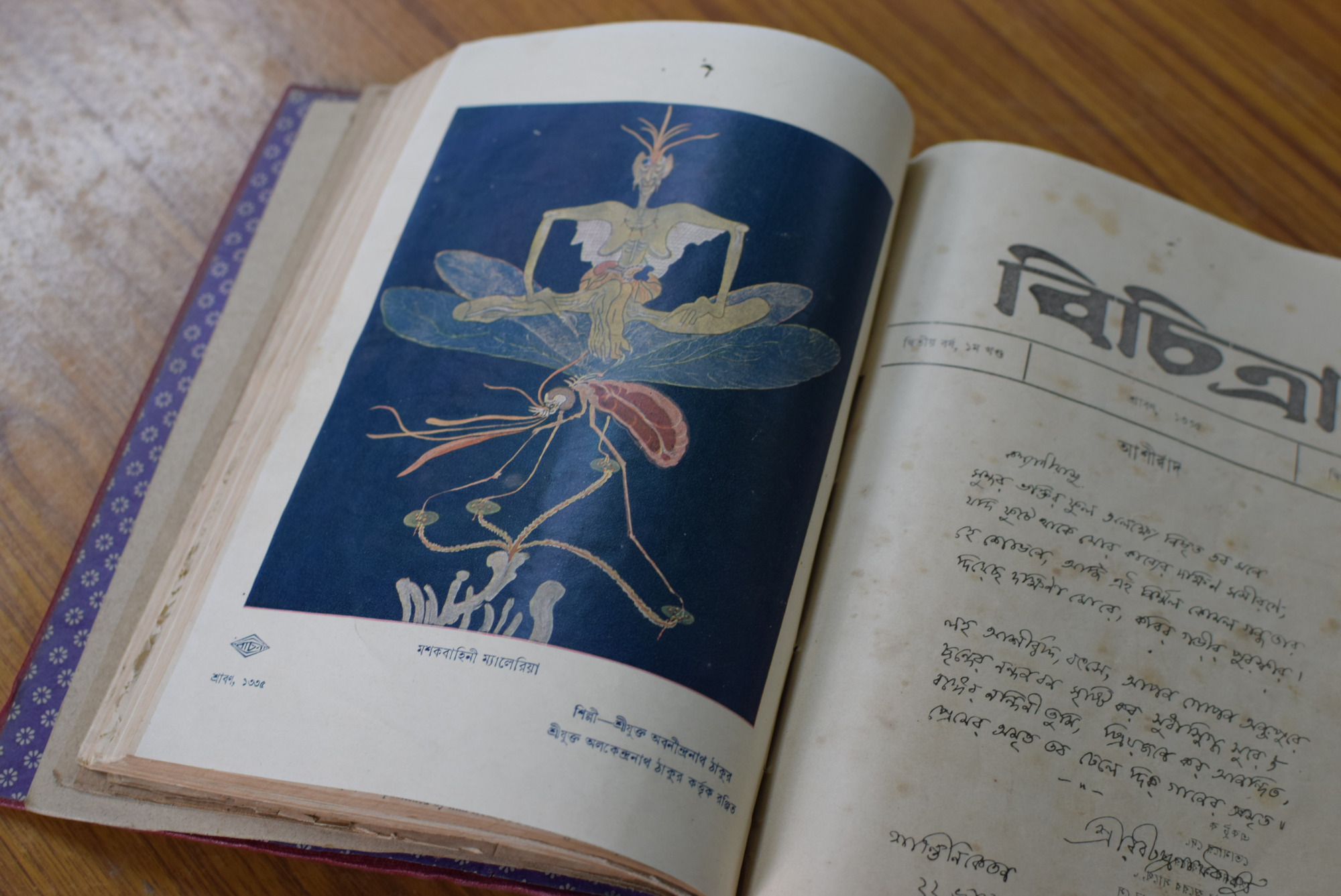

Abanindranath Tagore

Mashakbahini Malaria (Malaria carrying mosquito)

Bichitra (July 1928)

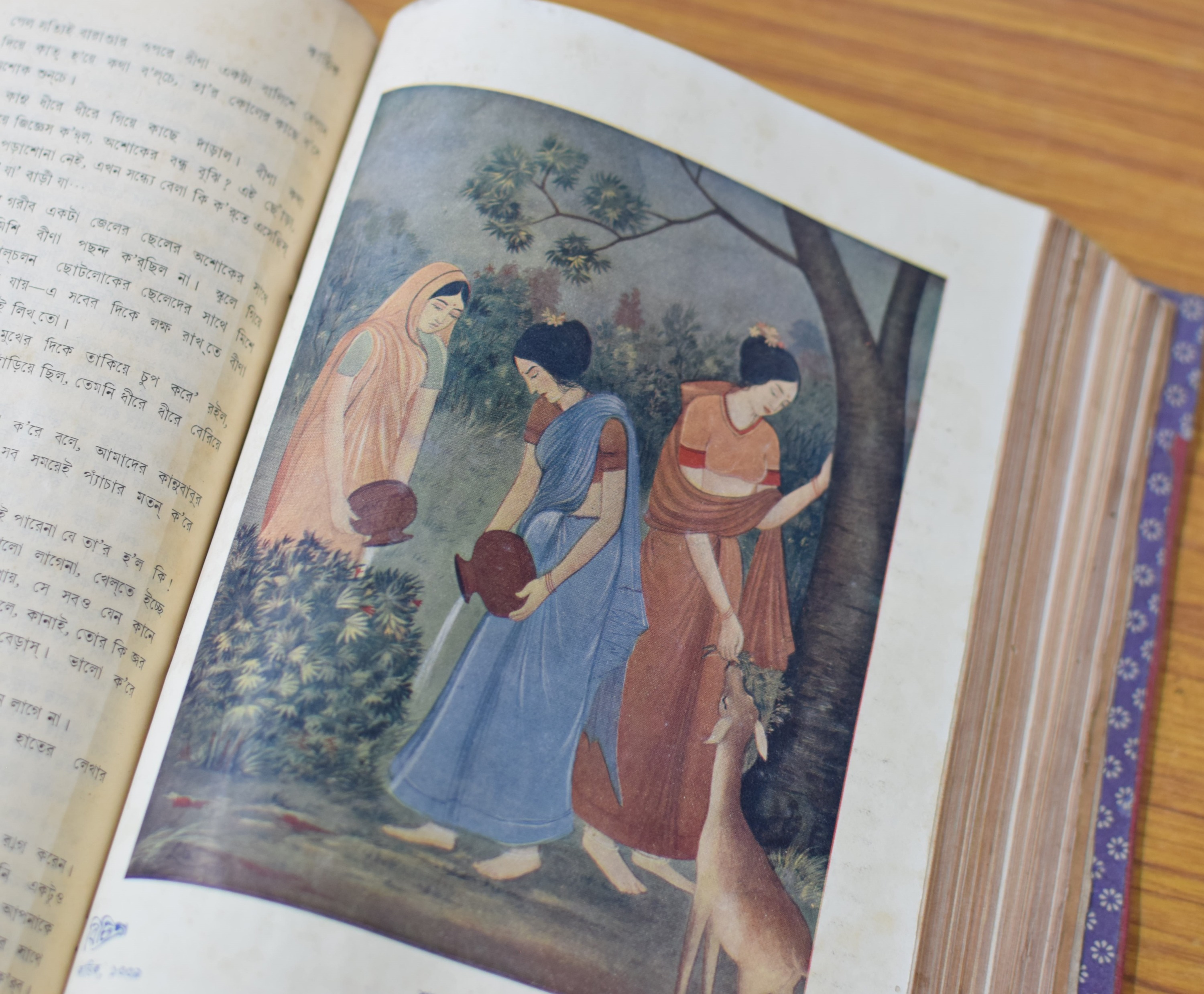

Lila Mitra

Sakuntala

Bichitra (February 1928)

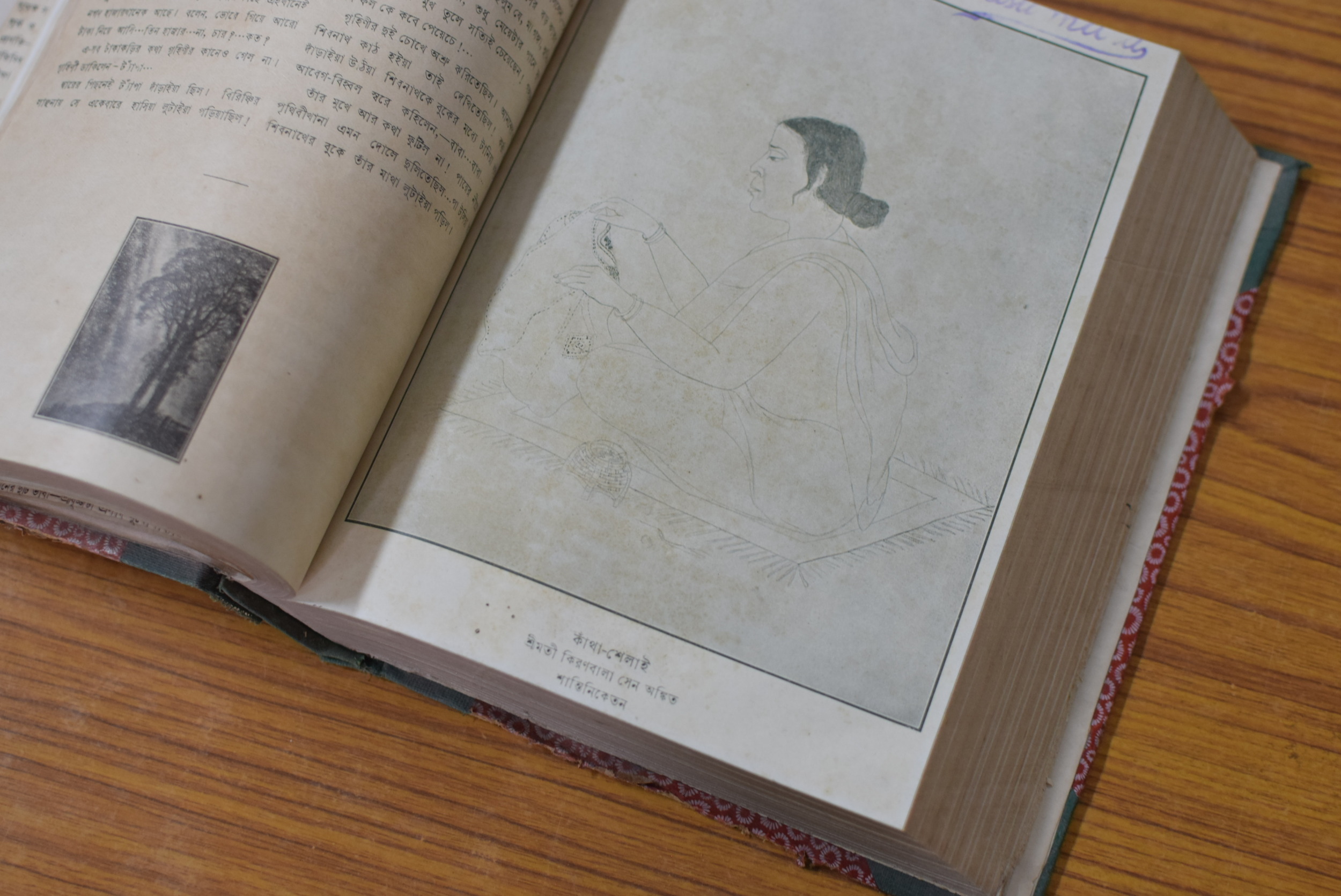

Kiranbala Sen

Knatha Shelai

Bichitra (July 1927)

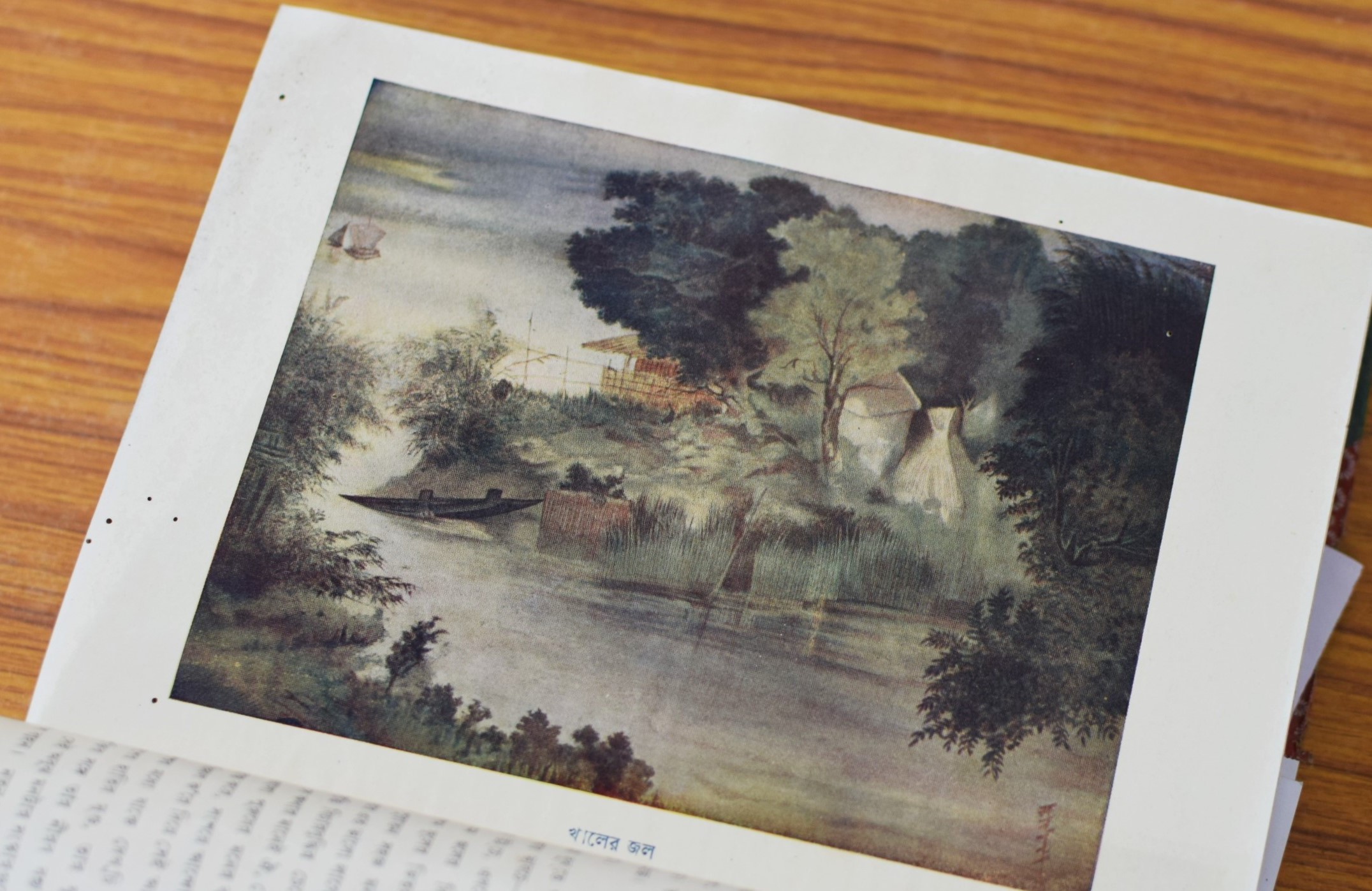

Abanindranath Tagore

Khaler Jal (Pond water)

Bichitra (July 1927)

Bichitra’s pages unveil rare paintings and afford us a unique glimpse into unusual stylistic experiments of famous artists. Some such unique discoveries are Abanindranath Tagore's humorous wash painting of a malaria-carrying mosquito and Nandalal Bose's painting of Kali. We also come across female artists—from lesser-known names like Lila Mitra and Kiranbala Sen, to more well-known ones, such as Sukhalata Rao, among others. |

|

|

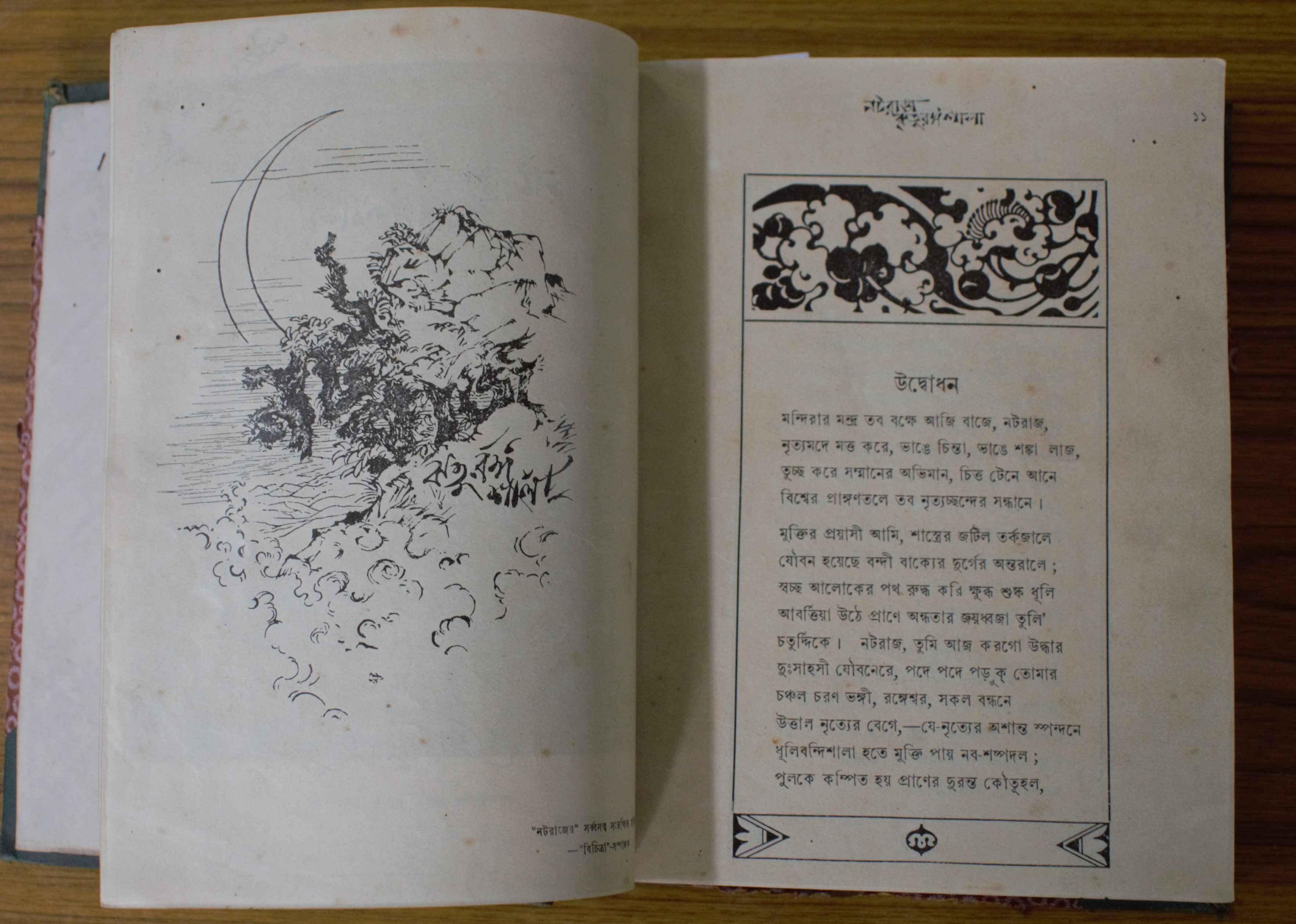

Nandalal Bose

Nataraj Riturangashala

Bichitra (June 1927)

Nandalal Bose

Nataraj Riturangashala

Bichitra (June 1927)

Tailpiece of a text

Bichitra

Bichitra's pages set up unique experiments between texts and images. The most memorable are Nandalal Bose's illustrations of Rabindranath Tagore’s Nataraj Riturangashala, a magnificent poetic work, which devoted one verse to each season. Tagore's poems were often printed with exquisite pencil drawings, probably by Nandalal Bose. Here, Nandalal's illustrations clearly do much more than illustrate the text. The text simply become prompts for great imaginative flourishes. |

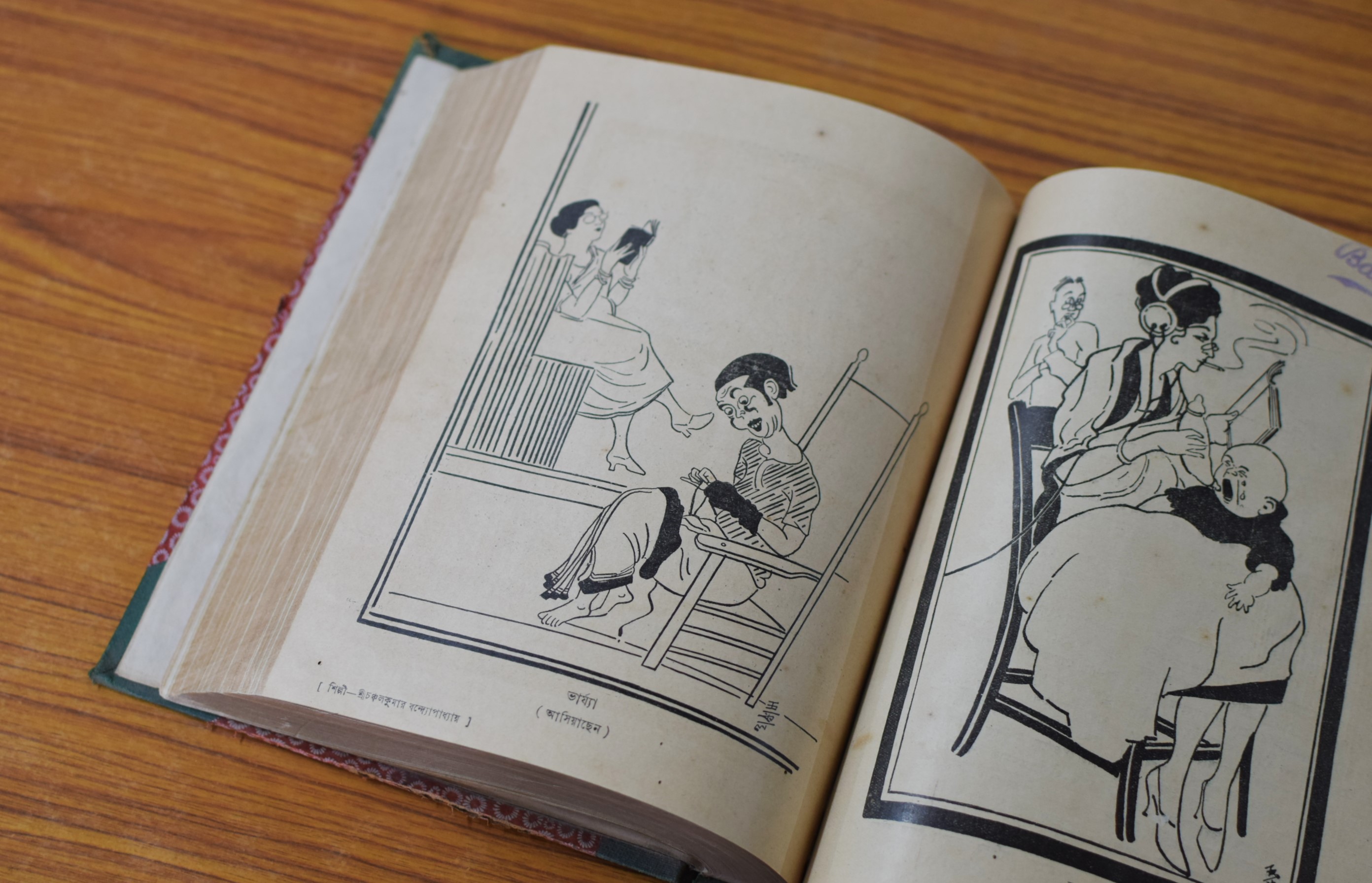

Chanchalkumar Bandopadhyay

Bharjya (Virgin)

Bichitra (1927)

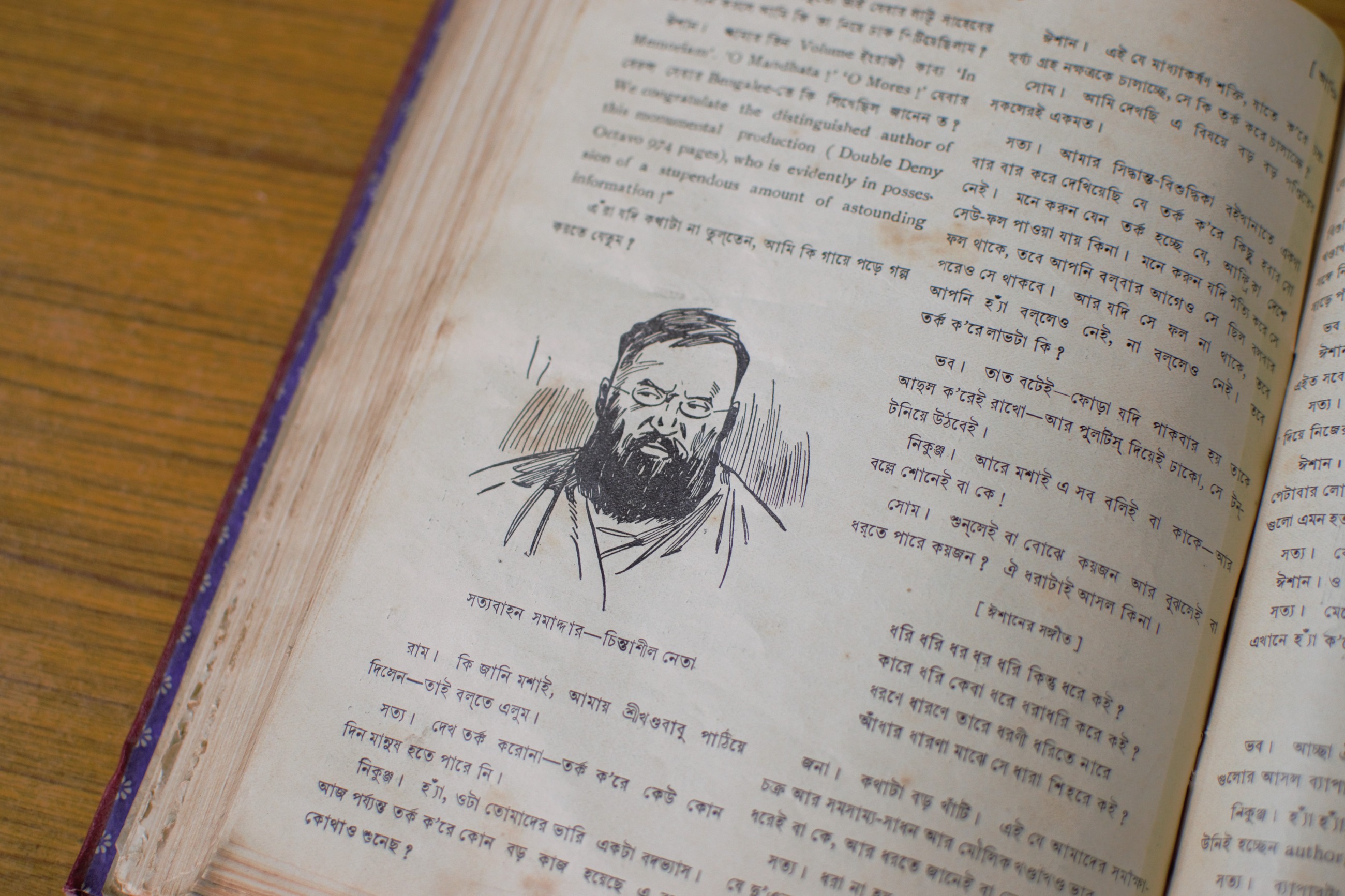

Jatindra Kumar Sen

Chalachittachanchari

Bichitra (1927)

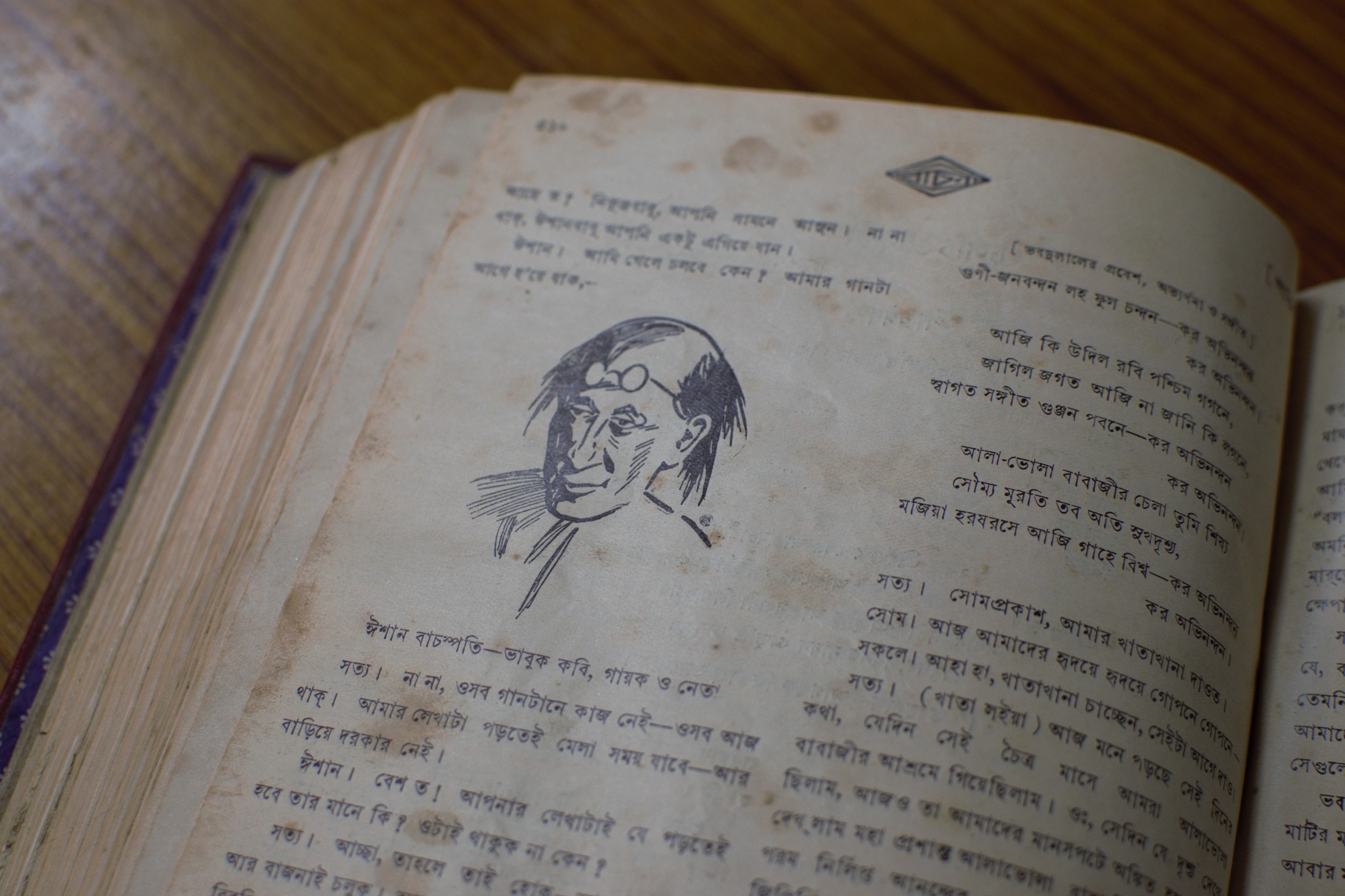

Jatindra Kumar Sen

Chalachittachanchari

Bichitra (1927)

Bichitra’s pages were replete with satirical sketches by the leading cartoonists of the time. Chanchalkumar Bandopadhyay takes digs at the ‘New Woman’ in a full plate spread while Jatindra Kumar Sen—an artist whose sharp imagination of portrait caricatures deeply inspired modernists like Paritosh Sen—illustrates Sukumar Ray’s topical satire Chalachittachanchari in Bichitra’s very first issue. |

|

CLOSING NOTES These illustrated periodicals don't just allow us to explore the images that shaped the lives of people in the past but open an archive full of surprises. A lot of these periodicals were made easily accessible through reading libraries in every other neighbourhood of Calcutta and its suburbs. Today, with the shrinking number of public libraries how do we envision a future of access to ‘fine art’ outside conventional viewing spaces like galleries and museums?

Photography Credits: Parameshwar Halder and Utsa Saha |

|

|

Sarbajit Mitra demonstrating

Main facade of Uttarpara Jaykrishna Public Library

Visitors explore the premises of the library

Visitors ascend the staircase of the library

References |