Archive Case Files

Archive Case Files

Archive Case Files

Valentine and Sons (publisher), Outwhiskered (detail), Lithograph, divided back, 1910s, Dundee (Scotland), 3.4 x 5.4 in. Collection: DAG

The DAG Archives travel to schools and colleges for the first time with a new education programme—Archive Case Files. Follow the journey of these students as they work with a collection of World War I postcards, to learn more about the role of visual archives in the classroom.

How do you read a postcard?

How did you study history? What are the images conjured in your mind when you think of a major historical event, such as the First World War? Can you think of where you have encountered such images?

Visual Archives in the Classroom: DAG’s Archive Case Files

Often when studying history, the only visualisations available to us of what is being studied are in the form of grainy images in the textbook. With some events, we may also have access to visuals from popular culture such as films and T. V. shows. Even when we are familiar with historical images, it is usually in digital formats, precluding the possibilities of considering the image as an object or evidence of something; they do not allow us, usually, to explore and investigate the tactile stories and narratives contained within the image object or accounts about how it was produced, used, disseminated or consumed. Archive Case Files, DAG’s newly launched education programme, using objects from its very own Archive, explores the avenues of learning history through the investigation of primary visual sources.

|

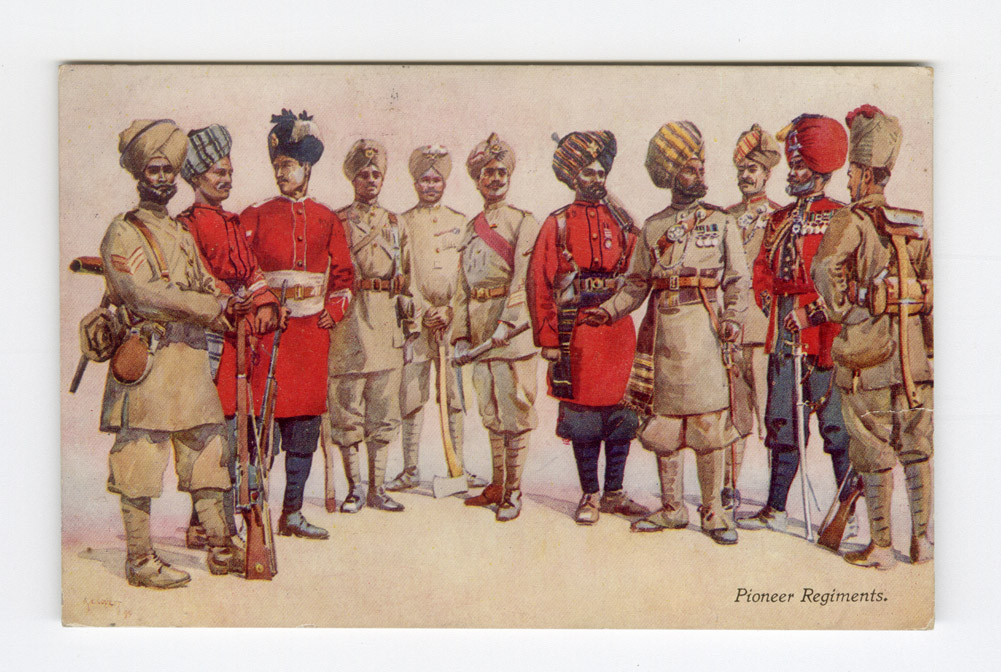

A. & C. Black, Ltd. (publisher), Pioneer Regiments, Coloured halftone, divided back, c. 1911, London (England), 3.4 x 5.4 in. Collection: DAG |

The DAG Archive and its collection

The DAG Archives has a vast collection of rare objects relating to the art and visual cultures of India, and we began with the idea of making parts of this collection accessible to students. Drawing from a collection of hundreds of picture postcards we curated a selection from the First World War. Many of these postcards had personal missives written on them, some had markings of usage. The First World War is part of history curricula across educational boards, and more importantly, is a significant feature of our popular historical consciousness. We wanted to examine these postcards to see what they could add to our knowledge of the Great War.

Unidentified Publisher, Les Uhlans aux Prises Avec Les Lanciers Indiens, Lithograph, divided back, c.1914, Paris (France) , 3.4 x 5.4 in. Collection: DAG

Archive Case Files- WWI Module

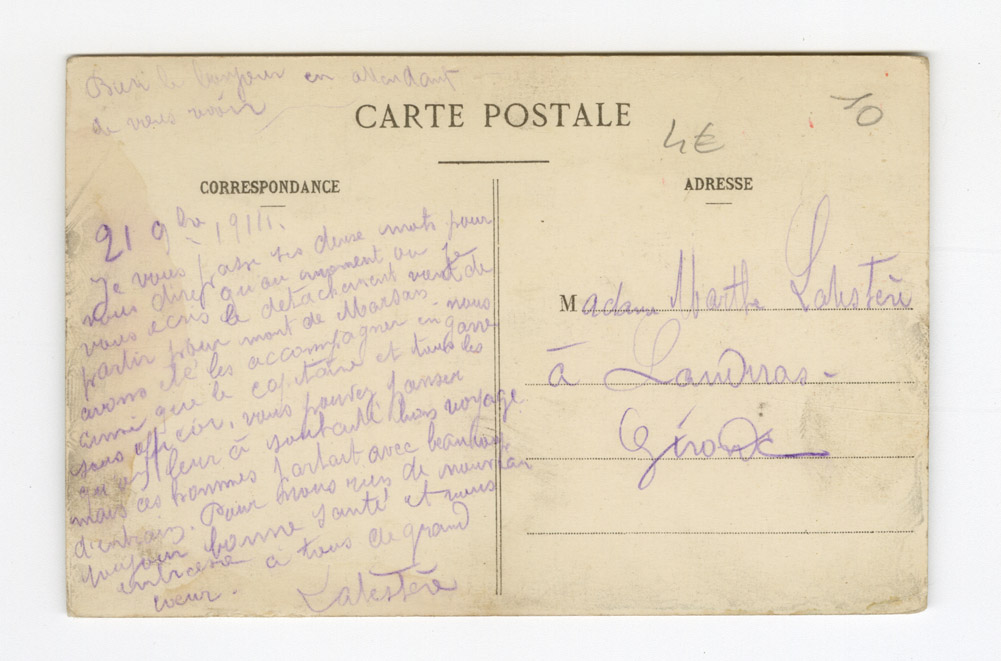

Did you know that over a million Indian soldiers served in the First World War? The collection of postcards we curated depicted these Indian soldiers, some posing in war regalia, along with portraits, captured during intimate or everyday moments in camps. High quality facsimiles were produced from this collection, which travelled to schools and colleges. The students began by ‘reading’ these postcards without any context or information about them. They were asked to choose one which intrigued them and then provided with prompts for visual analyses. While our aim was to parse the image on the postcard in a detailed manner, we also wanted to consider the social life of the object, that is the biography of its production and use. Despite being facsimiles, they were produced in a fashion that included markings of usage and wear. The analytical prompts given to the students considered both the recto and verso, the image and text, symbols and markings.

How do you read a postcard?

One of the key aims of Archive Case Files is to promote evidence-based thinking and learning. The visual prompts developed for reading the postcards are two-pronged: one at the level of observation, and one at the level of interpretation, which needed to be backed by observations. Interpretation prompts are always followed by the question— ‘what makes you say that’? This helps articulate the process of fact production and encourages students to practice critical thinking and evidence-based analysis when viewing or reading images. The prompts also include considerations of text, symbols, and markings which allow for considering the visual in a holistic manner.

|

Unknown Publisher, Troupes Hindoues - 2e Serie - No. 1, Collotype, divided back, 1914, Toulouse (France), 5.4 x 3.4 in. Collection: DAG |

Some of the postcards have messages on them in French, which have been translated for the first time to make the objects accessible to the students. The observations from these readings are then recorded and become the evidentiary basis for the subsequent steps of the workshop. For instance, the printed caption on this postcard, in French, tells us that this is an image of Indian troops conducting bathing rituals with a smile on their face. A visual analysis, though, as the students pointed out, reveals the living conditions of the soldiers, especially with regards to sanitary facilities. This observation eventually became an important piece of evidence for the students as they set to find out more about the daily life of an Indian soldier in World War I and their condition of life in unfamiliar environments.

Devambez (publisher), Soldat Hindou - Soldado de las Indias, Coloured halftone, divided back, c. 1914, Paris (France) , 5.4 x 3.4 in. Collection: DAG

Unpacking the process of archival research

The next part of the workshop involves students identifying observations which they find most interesting. DAG’s Education Programmes are built around the idea of art’s potential for being a medium for learning-centric and enquiry-based learning—using the process of interpreting art as a means of providing learners with the freedom to choose what interests them, ask questions, and pursue research on the lines of their choosing. In Archive Case Files, students use observations derived from their readings of objects from visual archives—in this case, postcards—to find points of enquiry to pursue. Another layer to the research process is introduced where readings of secondary sources—books, articles, essays and testimonies—are connected to the readings of the postcards, which constitute the primary sources.

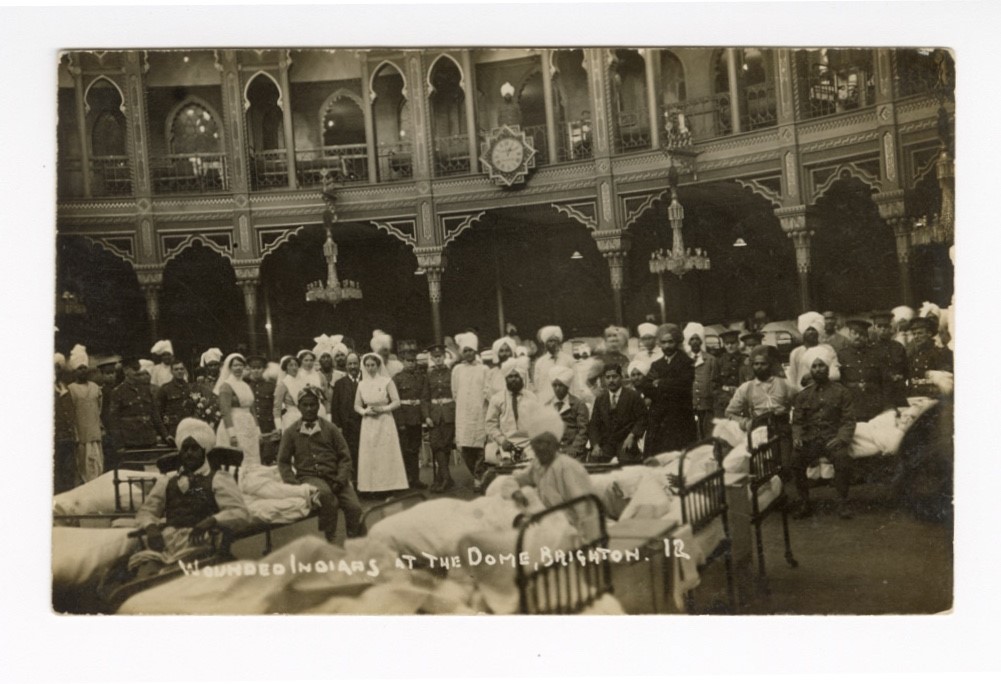

Unknown Publisher, Wounded Indians at the Dome, Brighton, Real photo postcard, divided back, c. 1915, 3.4 x 5.4 in. Collection: DAG

A carefully curated selection of texts enables students to contextualise and validate their observations. For instance, when examining a postcard depicting Indian soldiers receiving treatment at the Brighton Royal Pavilion, reading letters from Indian soldiers who were there—possibly even including someone in the image itself!—found in David Omissi’s book Indian Voices of the Great War, deepens their understanding. This approach also allows students to cross-check the descriptions in the text against the image, enriching their engagement with both sources.

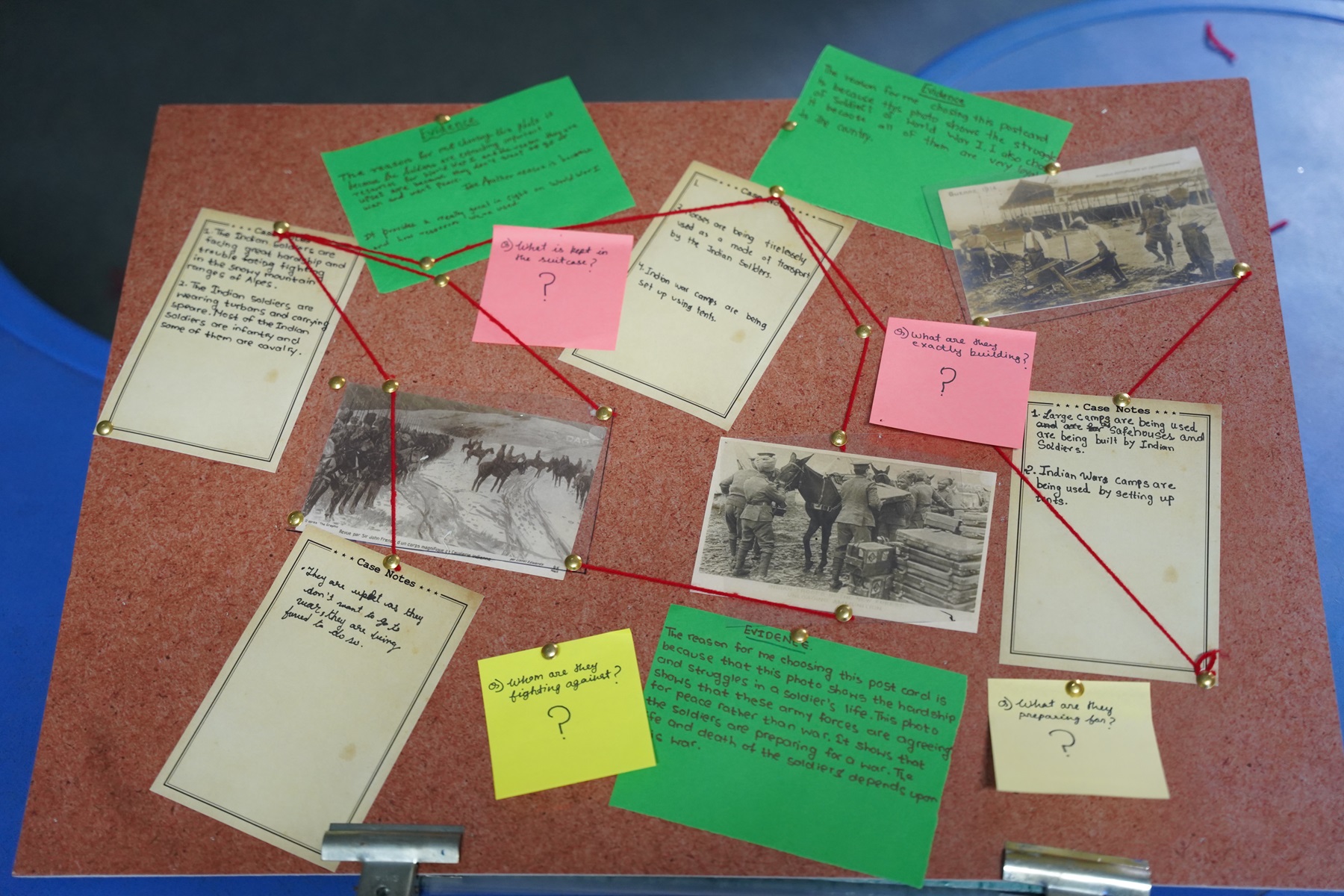

Visibilising the learning: Schools

As part of the outcome of the workshops, students make a visual representation of their research process to present their findings for a final sharing and discussion with their peers at the end. Working in groups of five or six, the students start by discussing their individual observations with their group members. They work together to find intersections between their points of enquiry and as a group decide their research question. They then collate their observations and find connections between them to allow for a narrative to emerge. This narrative is then presented in the form of a ‘mood board’ where they annotate the postcards with observations and use threads to connect them and organise them in a way that conveys the narrative that has emerged from their research. For instance, one of the groups asked: ‘What kind of work were Indian soldiers engaged in during the First World War?’ Or, as another group asked: ‘How did the French perceive the Indians fighting in the War?’ This process allows students to synthesise and share their research with each other in a visual format, which not only lays out the primary sources in juxtaposition with the students’ engagement with them (in the form of annotations), but also leaves space for further enquiry. Students are encouraged to ask each other questions, as well as leave any remaining questions and things they would like to learn more about on sticky notes on their boards.

A mood-board, prepared by student participants of Archive Case Files for schools. Photographer: Adrija Samal

Visibilising the learning: Colleges

To add another layer of critical rigour to the workshop module for college students, we introduced thematic readers curated around questions of physical repercussions of war, the spectacle of battle and combat warfare, life of Indian soldiers in enemy camps, and the administration of health. Such clusters become the basis for group formations among students to research Indian participation in the First World War from diverse perspectives. The participants work together to flesh out analytical frameworks presented to them by mapping chosen postcards across concepts and critical enquiries emerging from secondary readings. They are encouraged to storyboard their ideas as questions begin to organise themselves into narratives that are as visually eloquent as they are informative. Getting students to ponder on the composition of images, their changing meanings depending on the context within which they are viewed, and the importance of historically approaching the materiality of archival objects, are some of the larger concerns of this programme.

One of the photobooks prepared by a student participant of Archive Case Files for Colleges. Photographer: Adrija Samal

We invite archivists and scholars working on visual cultures in the fields of war studies and military history to help shape the students’ approach to visual objects as historical evidence. Critical artistic forms like the photobook are introduced at a later stage of the workshop to enable students to challenge the hierarchy between text and image, and to go beyond a merely illustrative understanding of visual material. During the past two college editions, students got the opportunity of working with visual art practitioner Ushnish Mukhopadhyay to present their research in the form of photobooks that they designed and put together from scratch. Over the course of making photobooks participants learn new and exciting ways of mediating the images they engage with to tell a compelling story. It allowed them to delve deeper into the politics of image-making, and into various modes of reproduction and circulation of images.

A College student participating in an Archive Case Files workshop. Photographer: Adrija Samal

Archivists and historians of the future

One of our aims with Archive Case Files was to explore the role of visual archives in the classroom; and experiment with ways in which archival sources can interact with and extend beyond the existing curricula taught through textbooks.

Paulo Freire, in his essay ‘The Act of Study’, writes that a ‘critical attitude in studying is the same as that required in dealing with the world (that is, the real world and life in general), an attitude of inward questioning through which increasingly one begins to see the reasons behind facts.’ Through the process of Archive Case Files, the usage of visual archives reaffirmed the significance of visual literacy and critical questioning where students at every step had to ponder upon the question of where ‘facts’ come from and ask themselves through every step of the process: ‘how do we know what we know?’

Archive Case Files is our way of sharing unseen ephemera from our extensive archive with schools and colleges, hoping to impart a sense of excitement to young learners as they step into the shoes of historians and archivists. We hope this experience can be an encouragement for these students to sustain a sense of curiosity when it comes to engaging with visual archives.

Collating material at the Archive Case Files workshop for Schools. Photographer: Adrija Samal

Collating material at the Archive Case Files workshop for Schools. Photographer: Adrija Samal