test

Practicing Feminist Art: An Interview with Rekha Rodwittiya

Practicing Feminist Art: An Interview with Rekha Rodwittiya

Practicing Feminist Art:

An Interview with Rekha Rodwittiya

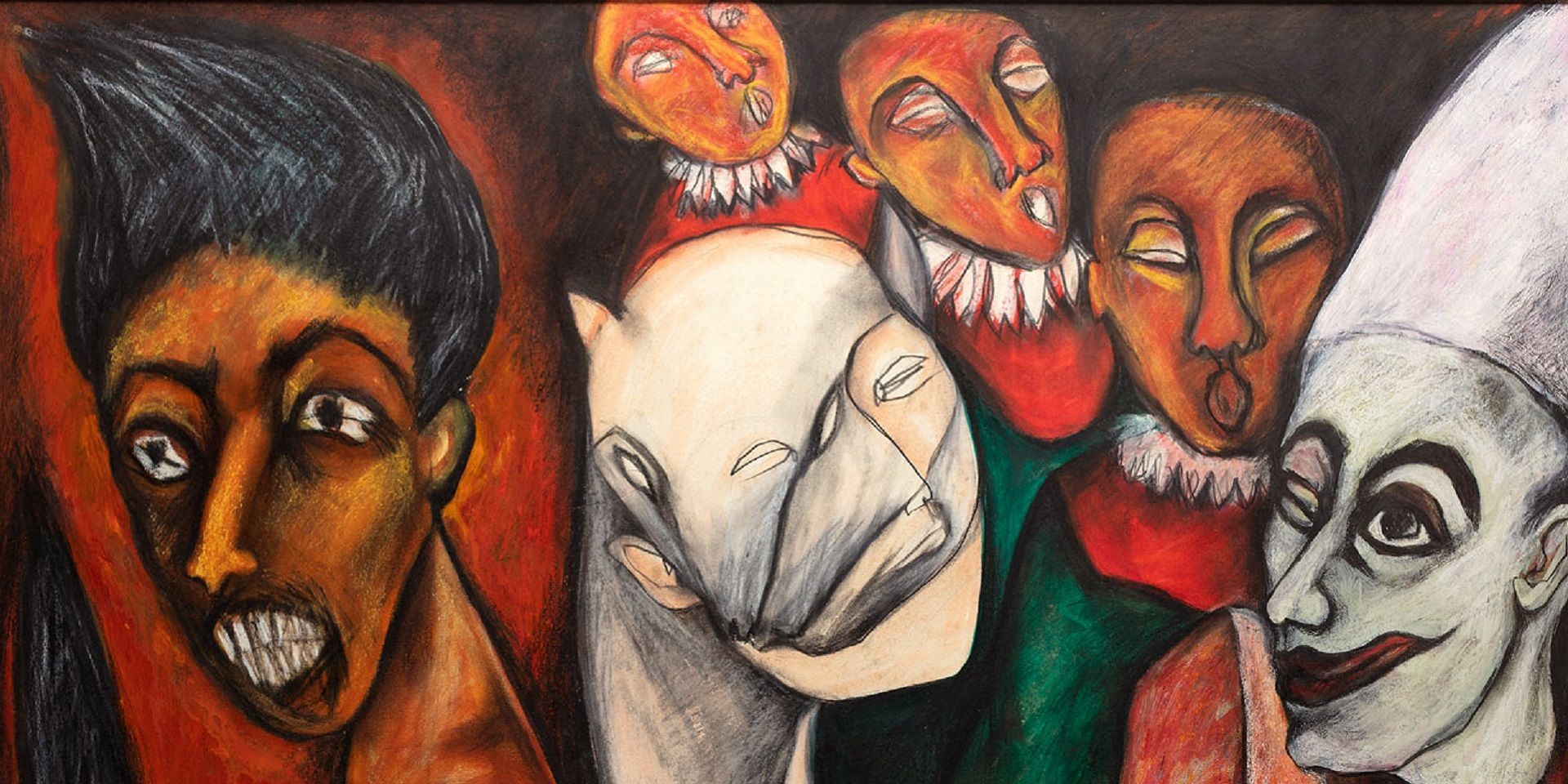

Rekha Rodwittiya, The Parade (detail), Gouache, pastel and graphite on paper, 72.0 x 36.0 in. / 182.9 x 91.4 cm., 1986. Collection: DAG

Rekha Rodwittiya is a contemporary Indian artist and pedagogue, associated with the Baroda School at M. S. University, Baroda (now, Vadodara).

Known primarily for her allegorical paintings, she blends parables, metaphors, allegories, myths, and legends to give her work added layers of meaning. Rodwittiya has represented India in several prestigious art shows internationally and has conducted a series of workshops and lectures on Indian art. She conducts an art studio in Vadodara called The Collective Studio, jointly with her husband and artist Surendran Nair. She spoke to the DAG Journal, outlining her formative influences, her pedagogic styles and influences, and the trajectories of her own practice.

Q: In your practice you incorporate certain elements of storytelling and myth-making, employing metaphors and allegories without really suggesting a fixed meaning or narrative. How do you control or arrive at this process of meaning-making?

Rekha Rodwittiya: My area of focus resembles a garden—a tiny plot of land that I continually cultivate, till, plow, and harvest. What I mean by this is that my area of interest primarily revolves around the lives and narratives of women, including stories about gender from a feminist perspective. The politics of a region, the geography of a space, and the hierarchies of existence that give rise to oppressions and suppression, all in relation to how women are positioned within these contexts, serve as the trigger for me to discover meaningful content and purpose within my work.

Over time, everyone, including you and I, tends to use the same alphabets to form words in spoken language. However, the way we arrange and deliver these words differs. The grammar's syntax and how we organize our thoughts naturally influence the content, allowing individuals to express themselves uniquely. Personally, I have focused on shaping my ideas around the human figure, incorporating everyday elements into my work. Where you live also shapes your perspective, so I choose to reside in India due to political reasons. When it comes to defining my content as an artist, I can't envision being anywhere else but in India. This doesn't necessarily mean I exclusively tell stories about India. However, I can empathize, understand, and connect with the human predicaments I discuss because I find my compassion and comprehension more profoundly in this context.

|

Rekha Rodwittiya, How Much Lower Can The Coffin Go, Oil on canvas, 83.1 x 52.1 cm., 1985. Collection: DAG |

Q. How would you describe your relationship with your own work, and the motifs you are regularly drawn to? Is politics—especially feminist politics—intrinsic to your vision of art and the world?

Rekha: Not many people know that at the age of 13, I made deliberate choices that shaped my beliefs. For instance, I decided to abandon religion when I was at that age. I come from a background where my father served as a fighter pilot in the Indian Air Force, and I believe that certain life experiences compel you to perceive life more intensely than others might. I grew up in a family where being a girl child held immense value. Right from my birth, I was entrusted with the legacy of belonging to something precious, something to be cherished and held with great responsibility.

I mention this as a preface because it truly forms the metaphorical playground of my upbringing, enabling me to find my own path, even if that meant changing directions from time to time. The feminist perspective was not something I adopted later in life; it was ingrained in my upbringing. I recognized the responsibility of not only defining my own existence but also considering how my gender was perceived externally.

For me, my identity and my art are intertwined. I approach everything I do and all my concerns through the lens of gender perception and feminist issues. Making art is my core. I structure my life around it. Everything else I do is a means to manage my time effectively so I can spend more time in my studio.

What deeply affects me is observing how women face the daily challenges of confronting a patriarchal and traditional underbelly in their lives and emerge as survivors. I don't view the world solely from my individual perspective but through the lens of how my gender is impacted and the hurdles one must overcome, like in a steeplechase. I am constantly influenced by the personal politics that shape my life. This means that I don't create art in isolation from the political ideals I choose to embrace. I aspire for an egalitarian space, one where true equality thrives. I am particularly passionate about fair economic labor distribution and the recognition of the female voice as equal.

In a country like India, which operates under a caste-driven hierarchy, we claim to be a pluralistic society but are starkly divided in our everyday politics. This division is evident in our governance and the way we exclude communities from mainstream India. This reality deeply concerns me.

It's insufficient to dismiss these problems just because they don't directly impact my personal life. Even if I lack the influence to change entire systems, my power as an individual, like everyone else's, lies in our ability to vote, voice our opinions, and resist. We possess the capacity to engage, encourage, and progress. All of these actions contribute to the shared environment of everyday life, reminding each of us that, regardless of our specific roles—and I happen to be a painter—our actions matter.

|

Rekha Rodwittiya, The Parade, Gouache, pastel and graphite on paper, 182.9 x 91.4 cm., 1986. Collection: DAG |

|

Rekha Rodwittiya, The Circus Trainer, Oil on canvas, 53.8 x 44.5 cm., 1984. Collection: DAG |

Q. Do you see your art as a form of activism?

Rekha: I want to clarify that I don't identify as an activist; I see myself as an interventionist, and a bridge. I'm uncertain if I'd categorize my work as political art; that's not my intention. However, the politics of my existence and the purpose behind why I engage with life as I do should and must be evident within my artistic practice.

For instance, I'm currently working on a series titled ‘I Am Woman, Do Not Whisper It.’ This title wasn't randomly chosen; it encapsulates the essence of my ongoing exploration. I consistently delve into territories that inherently embody and reveal the politics embedded in my work. I don't aim to explicitly state what each emblem or motif represents; I don't adhere to that approach. Having said that, over the years – I'm now 64, having entered mainstream art at 26 – my artistic journey has developed into a pictorial lexicon, rich with meaning and intention.

Rekha Rodwittiya, The River of Dreams, Oil and acrylic on canvas, 177.8 x 236.2 cm., 1994. Collection: DAG

Q. In your work The River of Dreams, that is featured in the exhibition A Place in the Sun, there is a fragmentation of the female nude, and an image of the self confined within the boundaries of managing home. How does domestication factor in this visual? There are works that are self-referential in nature and then there is the use of self as the protagonist in your art. What role does self-image play in it?

Rekha: In my work, the central figure is always a woman embodying her shakti, irrespective of the challenges she faces, including the atrocities and difficulties imposed by patriarchal environments. She stands as a testament to resilience, capable of reviving hope and belief. She remains the nurturing force in life, even amidst adversity. This is how I depict my protagonist - as a symbol of enduring strength.

In this particular work, the focus isn't solely on domesticity. I employ the metaphor of a woman threshing rice grains to symbolize the harvest, emphasizing the significance of what is retained and what is discarded.

The domestic objects in the work may be interpreted in numerous ways. I vaguely recall a kettle, existing almost in a suspended, free-floating state. I firmly believe that you can't strip away the heart and soul of an individual, regardless of what possessions you take from them. Even in the face of extreme adversity—home destruction, rape, the degradation of women's dignity, looting, and plundering—people still seek ways to nurture life and be life-giving forces. This, I believe, is the underlying intention of my work, although it's not necessarily a narrative that can be explicitly told.

Rekha Rodwittiya, Untitled, Oil and acrylic on canvas, 120.7 x 120.7 cm., 1998. Collection: DAG

Q. Baroda as a space has always existed in the fringes of society, even in the context of art learning. You have put a lot of emphasis on the significance of learning art history as a practitioner. With a shift in the Baroda art school, the work of Nasreen Mohammadi, Jyoti Bhatt, and the critical interventions of someone like Geeta Kapur, how do you situate yourself in the changing landscape of Baroda’s modern art matrix, especially in light of your own non-traditional approaches to art education? Have these had an impact on your art practice?

Rekha: I believe I wouldn't have become the same artist I am today without the education I received. During my undergraduate years, I had the opportunity to interact with a diverse group of individuals. It's worth emphasizing the influential figures I encountered like Mildred Archer, Karl Khandalavala, Gieve Patel, Sudhir Patwardhan, and many others. Additionally, I had access to remarkable individuals such as K. G. Subramanyan. I must mention my deep gratitude to Nasreen Mohamedi, who was a disciplined and sharp-minded teacher, although her quiet demeanor might not have revealed it to many. Jyoti Bhatt and Gulam Mohammed Sheikh, whose passion for art history, coupled with his deep engagement in music, literature, cinema, and other cultural practices, infused our classrooms with vibrant energy. greatly influenced me in the realm of art history as well.

K. G. Subramanyan, Untitled (Woman), Gouache and graphite on paper, 25.9 x 25.9 cm., 1980. Collection: DAG

What made my educational experience truly transformative was the interdisciplinary nature of the college environment. While we had our separate departments, we were also part of a collective space where learning transcended boundaries. It felt like being part of a joint family, where everyone contributed to each other's growth. Our college operated from sunrise to sunrise, and I often stayed until 10 or 11 at night.

One of the standout figures in my educational journey was Jeram Patel, an exceptionally talented artist from the Faculty of Fine Arts, although he was designated for Applied Arts. He generously shared his insights with many of us who sought his guidance. Then, of course, there was my experience in London, which was truly remarkable. I was immersed in a different level of academic rigor and had the privilege of being mentored by an excellent teacher, Peter DeFranchier, to whom I am deeply indebted. As an educator, I have a unique approach. I firmly believe that learning should be continuous, a 24/7 endeavor. My role is to serve as a bridge, providing keys to those I interact with, keys that can hopefully unlock doors of understanding. I am a demanding teacher, drawing from the tradition of disciplinarians like Nasreen, Jyoti Bhatt, and Peter. They instilled in me the significance of being rigorous in teaching, setting uncompromising expectations for their students. This legacy has shaped my approach to education.

|

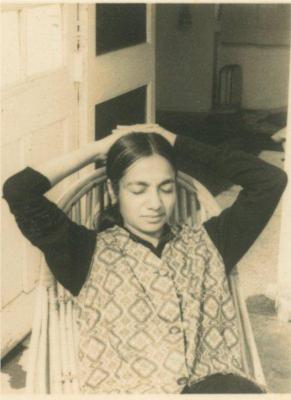

Nasreen Mohamedi. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

|

Jyoti Bhatt, Isolated, Oil on Masonite board, 57.2 x 76.7 cm., 1957. Collection: DAG |

Q. Visual images are now being circulated more than ever, especially on digital platforms. What importance do physical works and materiality hold for you?

Rekha: Undoubtedly, the importance of tactile and experiential interactions cannot be overlooked. However, not everyone has the privilege of accessing such experiences. In today's world, individuals, including children, can explore various subjects beyond art, such as menstruation, sexual orientation, sex education, health, women's issues, and children's needs. Access to this information is now more widespread, often without the economic barriers that were once present.

I am continually fascinated by the experiments and innovations arising from new technologies and scientific advancements. I adapt to them based on their relevance to my structured language. Nevertheless, at the core, I will always hold a brush or a pencil. The type of tool might vary, but this remains one of my primary means of articulating my thoughts and ideas.

|

Rekha Rodwittiya, And We Will Clap Whilst the City Burns..., Acrylic, dry pastel and graphite on paper, 152.4 x 91.4 cm., 1987. Collection: DAG |

Q. Even as forms of art-making keep shifting over time, some of the fundamental demands from it are probably constant. Can one say the same about A. I.-generated art that has taken a hold of people’s imaginations today?

Rekha: The evolution of artificial intelligence is inseparable from its historical context, a fact that intrigues me. Am I against it? No, I'm not. However, personally, I find value in imperfection. I often joke that I'm the creator of dots and wobbly lines, cherishing the imperfect nature of human touch. I appreciate the journey of negotiating our articulation to create the magic of art. We conjure when we engage with triggers, as these experiences are transposed spaces, not literal representations.

My approach involves observing the world, extracting elements, and then transforming them into transposed meanings from factual or literal impacts. I represent these in two-dimensional forms to initiate conversations or discourses. My goal is to prompt viewers to engage with the work based on their experiential lives. After that, I step back, becoming irrelevant. I don't stand as an intermediary to what I've created. I take the risk that empathy, identification, or resistance will allow the work to speak for itself and resonate with the audience.