After the Storm: Chittaprosad’s late oeuvre

After the Storm: Chittaprosad’s late oeuvre

After the Storm: Chittaprosad’s late oeuvre

collection stories

|

YOUNG CHITTAPROSAD: DAYS OF WORKING AS AN ARTIST-CADRE Chittaprosad Bhattacharya (1913-1978) was a versatile artist and a lifelong adherent of the socialistic worldview. In 1943, he traveled across the famine-stricken villages of Bengal and produced realistic sketches of human suffering that were regularly published in the pages of the Communist Party journal 'People’s War'. These sketches were later compiled and published as a booklet under the title 'Hungry Bengal'. Fascinated by his artistic skills, the General Secretary of Communist Party of India, Puran Chand Joshi took Chittaprosad to the Party’s headquarters in Bombay (now Mumbai). Bombay also happened to be a thriving center of cultural dissent as many prominent progressive writers, singers and theatre personalities were working towards building a cultural front of the Communist Party under the umbrella of Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA). Thus began another prolific chapter of producing sketches, drawings and paintings to document minutely many political events, most notably the Royal Indian Navy mutiny of 1946. Chittaprosad’s political caricatures of contemporary society and truthful documentation of socio-political issues in his distinct artistic style are etched in the public memory. |

|

|

|

In this story, we delve deep into the vast archive of Chittaprosad's estate that we had the good fortune to acquire from the artist’s niece Gargi Chatterjee in the early 2000s, to read some marks and shifts in the artist’s diverse oeuvre. The general atmosphere of negligence towards archival documentation of Indian artists and the various associations they formed during their lifetimes often results in pigeonholing the artist’s oeuvre into specific stylistic schools. We will see that, though popularly known as an agitprop artist-cadre of the Communist Party of India (C. P. I.) in the 1940s, Chittaprosad was doing a variety of very interesting formal experimentations till his final days. |

|

Chittaprosad, Untitled, mechanical reproduction on paper |

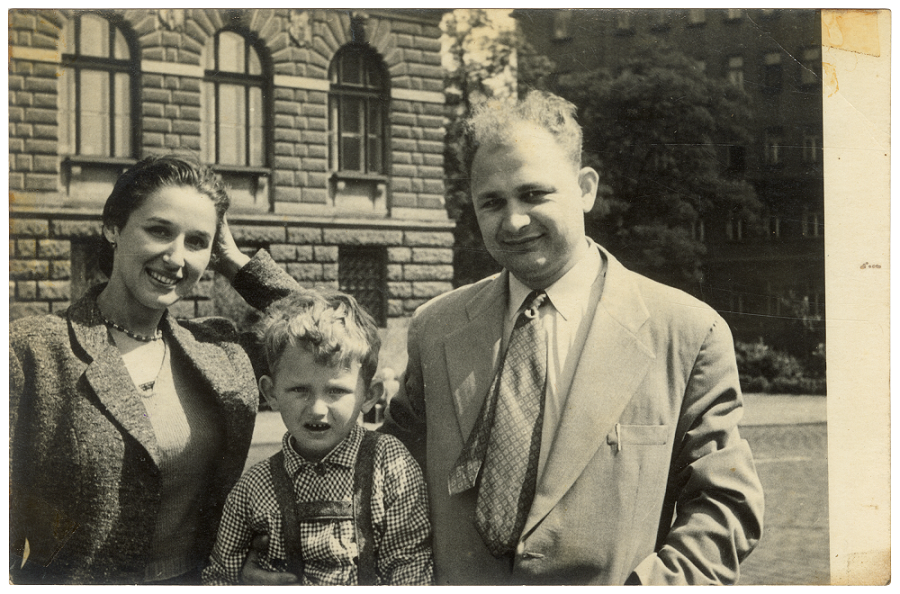

Couple portrait of P. C. Joshi & Kalpana Dutta

c. 1940s.

Silver gelatin print, 3.0 x 3.5 in.

Writer, filmmaker and political activist, Ritwik Ghatak

Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

THE TIMES THEY ARE A-CHANGIN': FALL OF THE CULTURAL FRONTFollowing the dissolution of the ‘Cultural Front’ of the C. P. I. at the Party Congress held in Calcutta (now Kolkata) in 1948—officially marking the end of the Joshi-ite (P. C. Joshi-led) period in the party—the heyday of vanguard cultural movements was over. As Ritwik Ghatak astutely noted in his fierce critique of the Party’s new cultural policies during this time, the most pertinent question concerning the cultural front was the 'crisis of cultural patronage' that was ordinarily fulfilled by the Communist Party until then. |

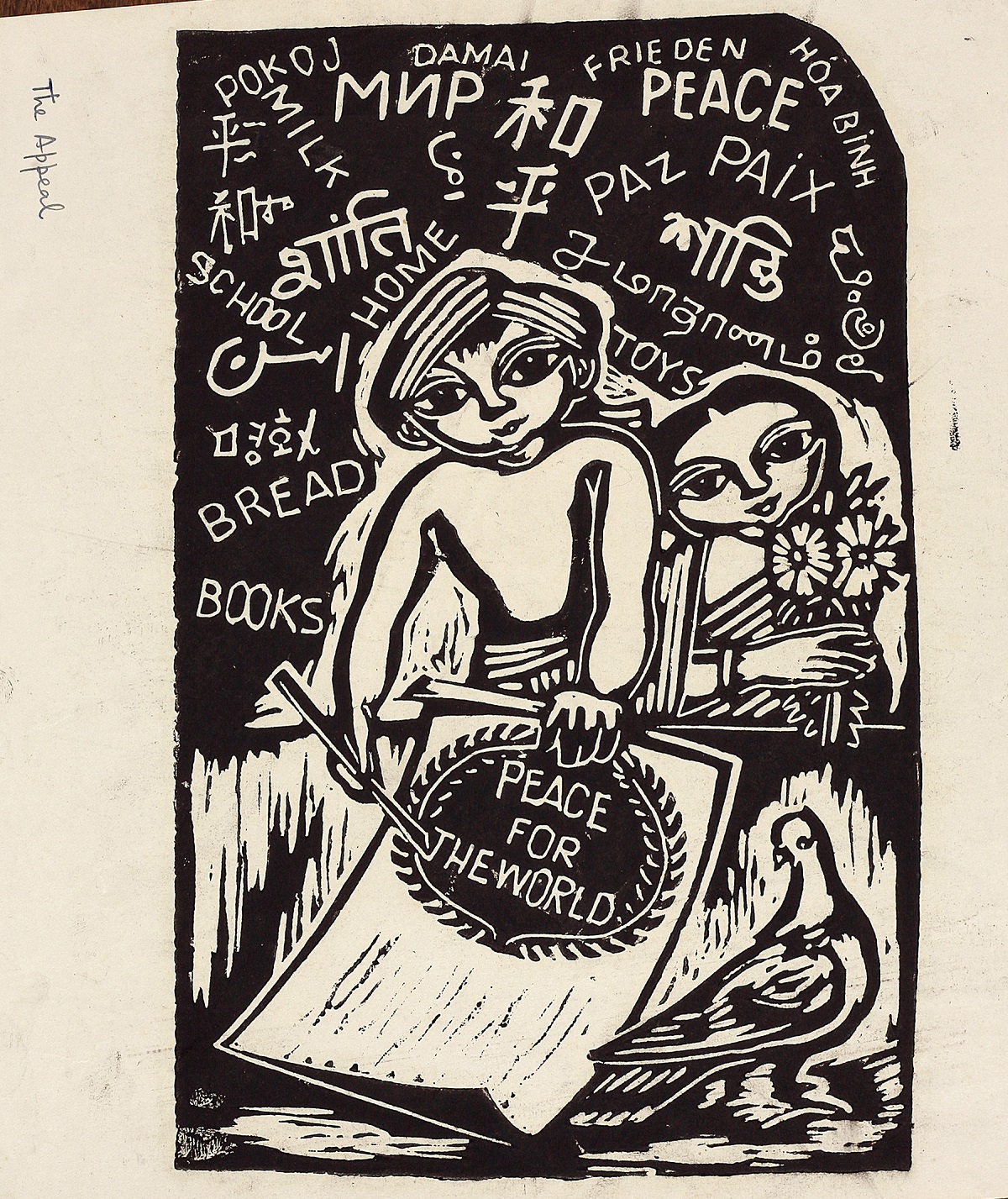

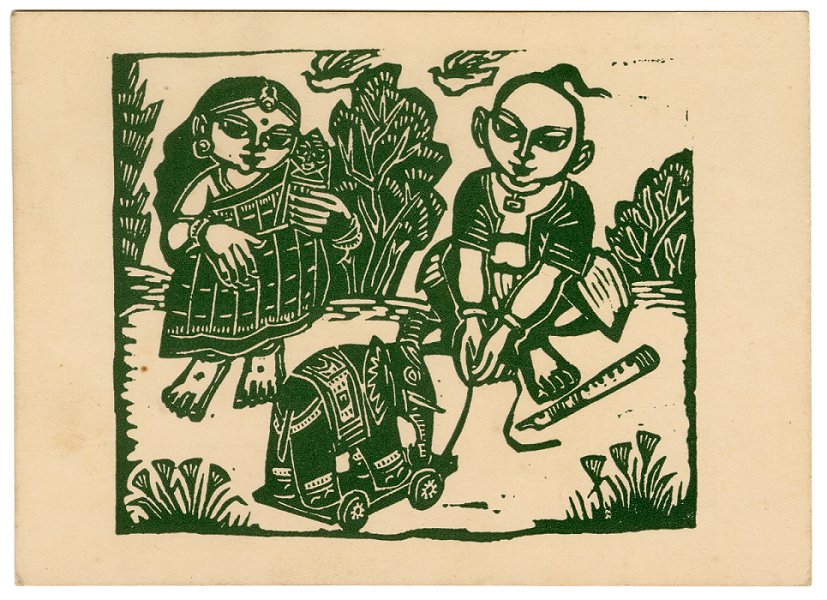

Chittaprosad

The Appeal

Linocut on paper

FORMATION OF THE PEACE FRONTThe period following India’s independence as well as the dissolution of the cultural front was a curious moment to search for new modes of artistic expression. Collective dissensus against empire in the previous decades was giving way to individualist critiques of bourgeois ideology in post-colonial Indian art. Despite growing disillusionment with the Party’s overall ideological stance and dwindling financial resources, Chittaprosad never ceased to create art. In the 1950s, as the Party’s focus shifted to building peace movements and an anti-imperialist Peace Front, we also find Chittaprosad working with a new visual language. |

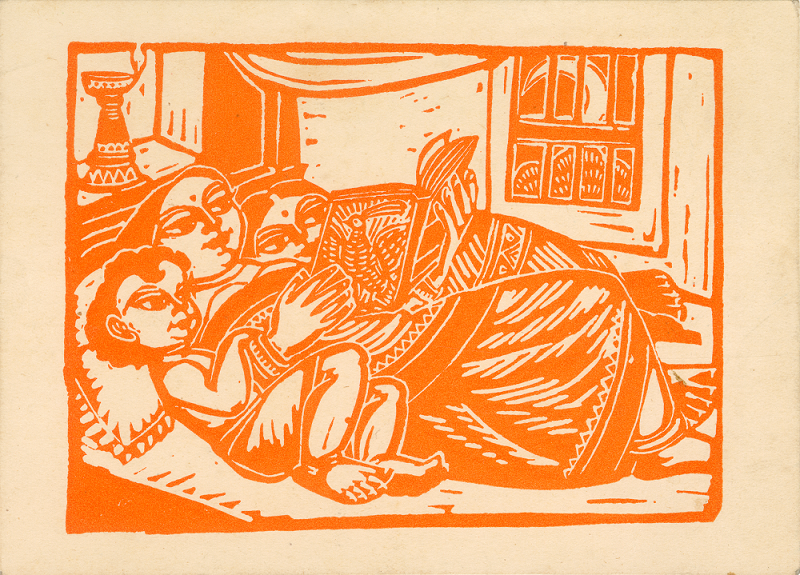

Chittaprosad

Monocolour Postcard printed in Denmark (set of 5), 4.0 x 5.4 in.

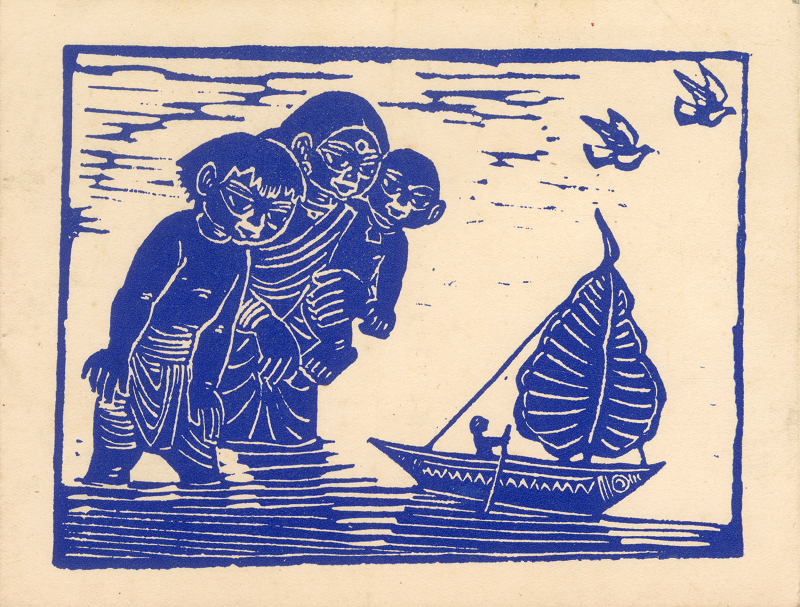

Chittaprosad

Monocolour Postcard printed in Denmark (set of 5), 4.0 x 5.4 in.

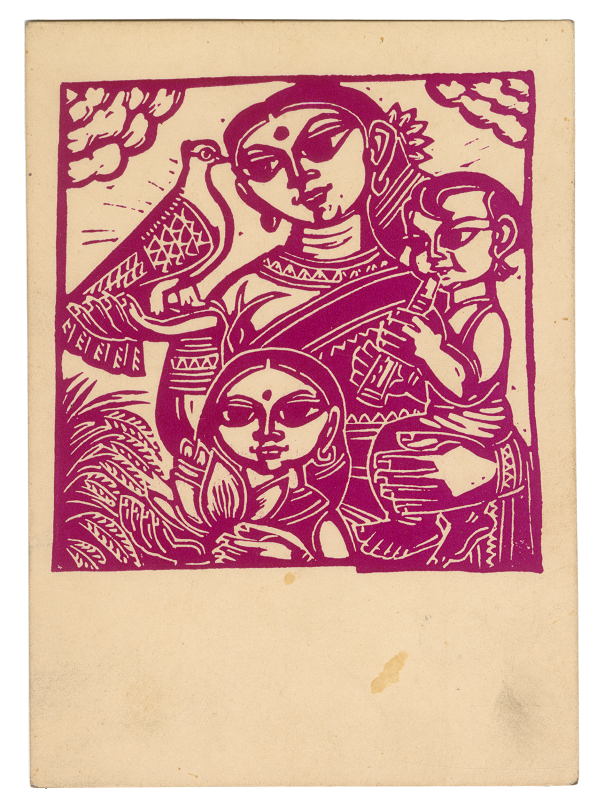

Chittaprosad

Monocolour Postcard printed in Denmark (set of 5), 4.0 x 5.4 in.

Chittaprosad

Monocolour Postcard printed in Denmark (set of 5), 4.0 x 5.4 in.

Chittaprosad

Monocolour Postcard printed in Denmark (set of 5), 4.0 x 5.4 in.

TOWARDS A NEW AESTHETIC: CHITTAPROSAD & FOLK ARTChittaprosad’s new visual vocabulary was informed by several factors. The vigorous, antagonistic, and ‘socialist realistic’ character of his earlier phase was substituted with a more empathetic, humanistic, often utopic, vision that does not seek to execute an instant, eviscerating critique of the present; instead, he seeks to evoke a vision of hope and universal justice that looks to the future. Borrowing from India’s rich traditional as well as folk art and crafts, he presented idyllic images of childhood as well as a harmonious communal life in his newly transformed art. |

|

This period in Chittaprosad’s oeuvre also saw experiments in themes and subject matters which are completely secular in nature. We also find in his art a poetic quality which urges us to appreciate a ‘Romantic’ in him. |

|

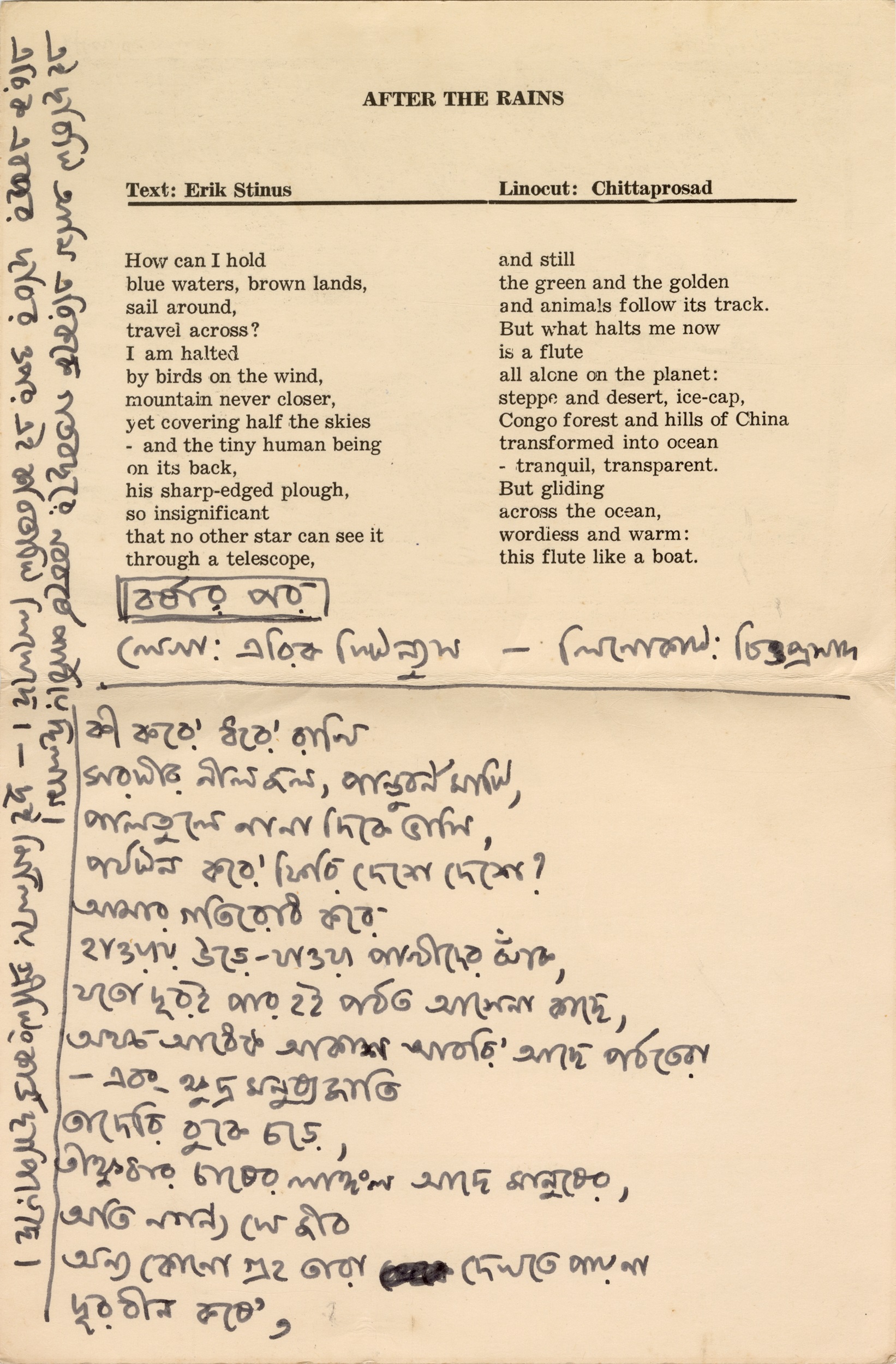

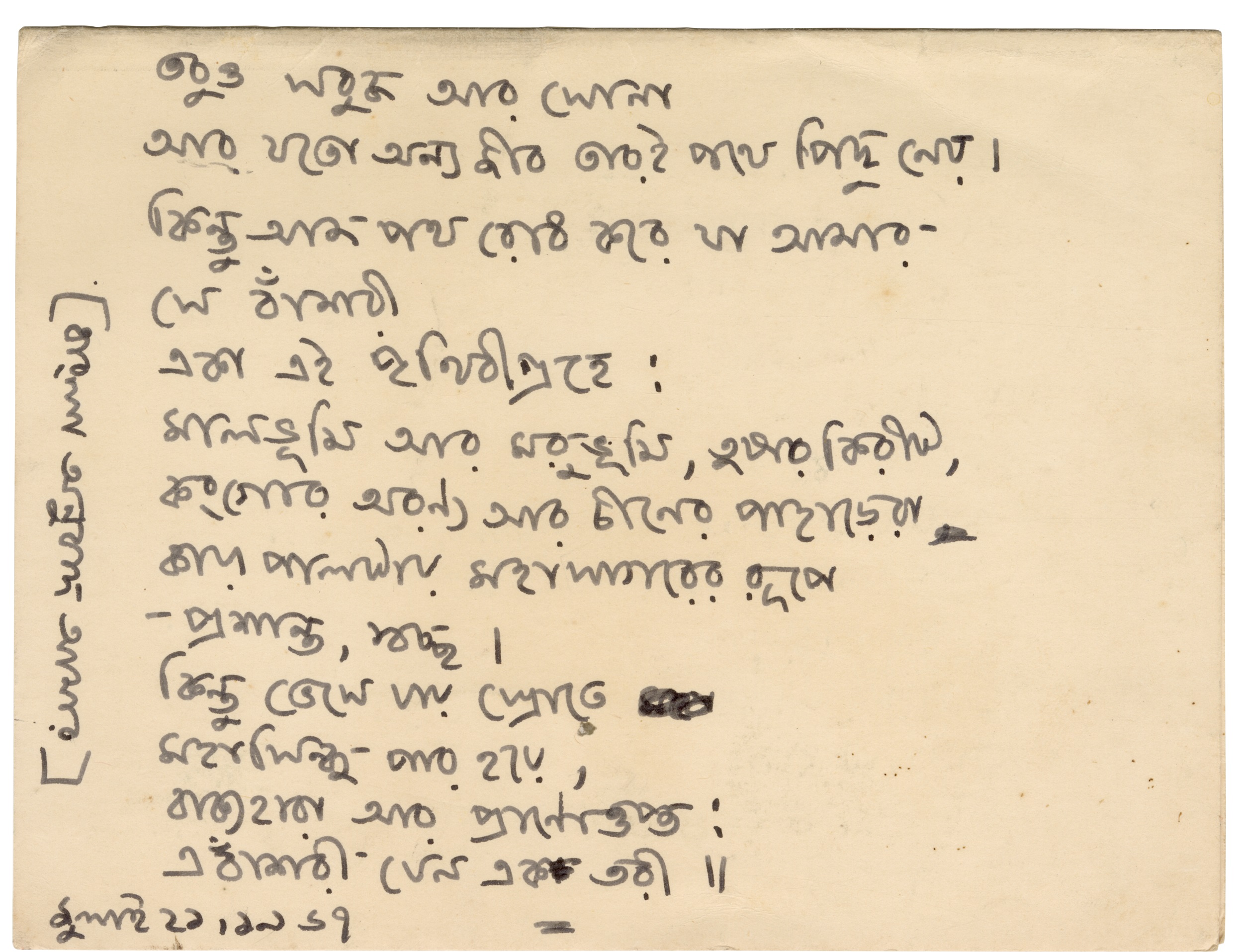

Postcard printed by Erik Stinus, with Chittaprosad’s linocut 'After the Rains' October 1966 5 x 6.3 in. |

Letters between Chittaprosad and Erik Stinus

Chittaprosad's Response

Chittaprosad

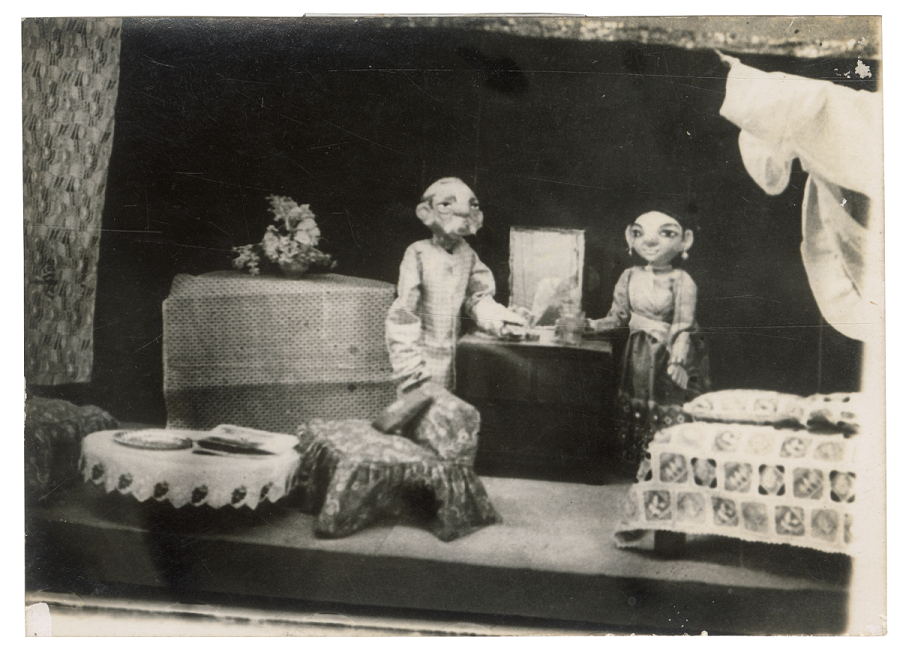

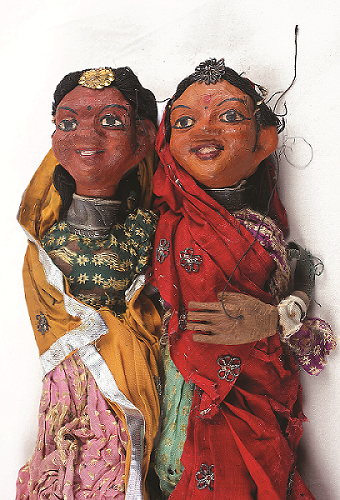

Photograph from a puppet performance, c. 1950s, 6.0 x 4.6 in.

Chittaprosad

Photograph from a puppet performance, c. 1950s, 3.4 x 2.4 in.

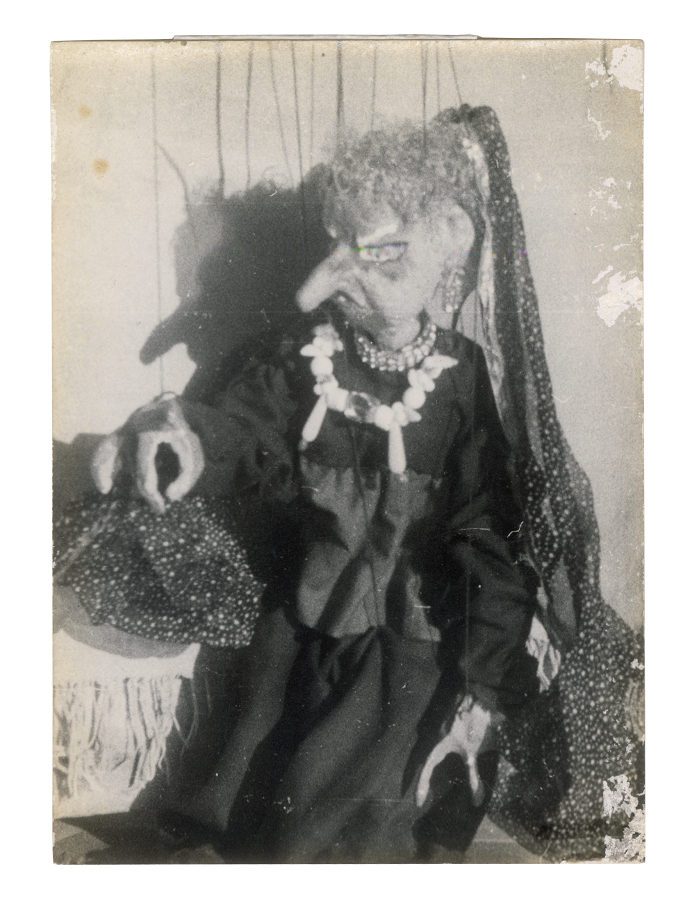

Chittaprosad

Photograph from a puppet performance, c. 1950s, 3.4 x 2.4 in.

Chittaprosad

Photograph from a puppet performance, c. 1950s, 3.4 x 2.4 in.

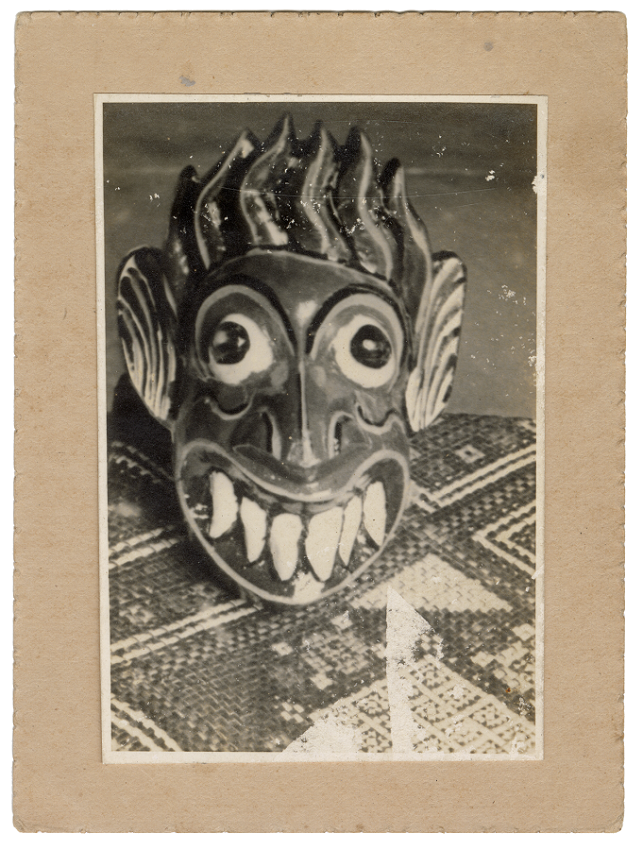

Chittaprosad

Puppet mask photograph, 5.0 x 3.6 in.

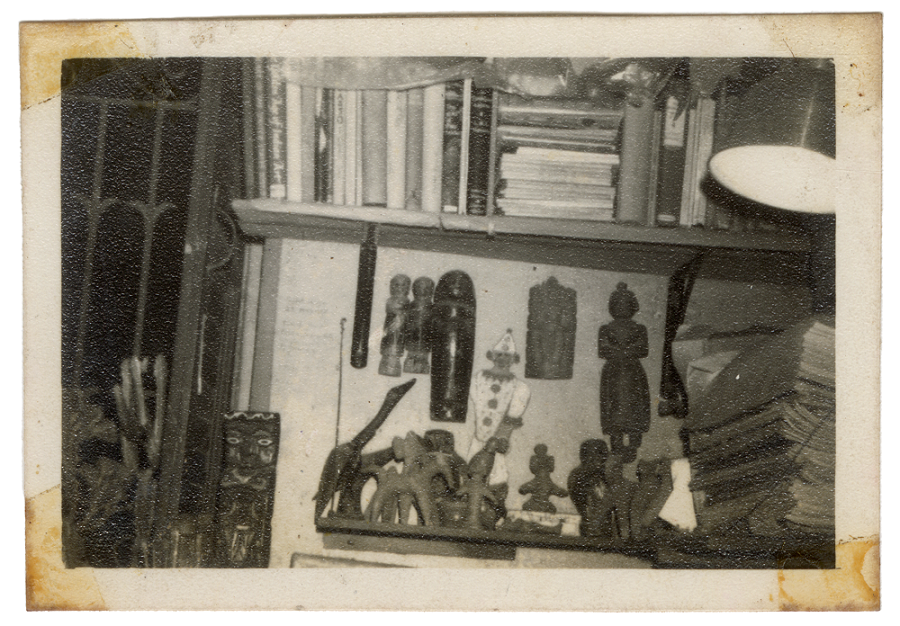

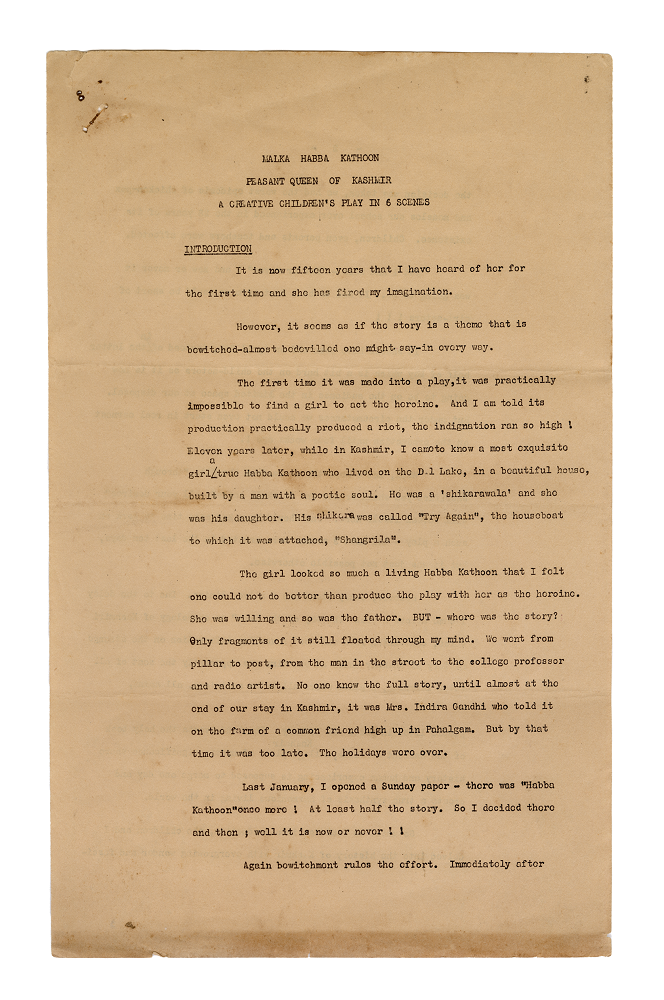

A CHILD’S PLAYHOUSE: EXPERIMENTS WITH PUPPETSOne of the primary experiments that occupied Chittaprosad in his late period was puppetry. As renowned puppet artist Raghunath Goswami noted, Chittaprosad’s puppets were animated by the means of pulling threads, which made it more akin to the ‘marionettes’, a tradition of puppetry prevalent in Europe. Goswami adds that his puppets bore a strong resemblance with indigenous figures. Indeed, in a letter to Murari Gupta, Chittaprosad expresses his intentions as the artist-craftsman: 'Since I am still under the spell of foreign prototypes, the puppets continue to follow a naturalistic schema. But other fresh plans are filling my imagination; (I) intend to 'puppetise' the folk wood and terracotta toys.' |

Chittaprosad

Quick setting gypsum plaster and fabric, varied dimensions

Chittaprosad

Quick setting gypsum plaster and fabric, varied dimensions

Chittaprosad

Quick setting gypsum plaster and fabric, varied dimensions

Chittaprosad

Quick setting gypsum plaster and fabric, varied dimensions

Chittaprosad

Quick setting gypsum plaster and fabric, varied dimensions

'From the early years of the sixties … Chittaprosad was beginning his experiments with puppets. I have heard they were exceptional creations. He looked after these puppets as if they were his children.' —Somnath Hore |

|

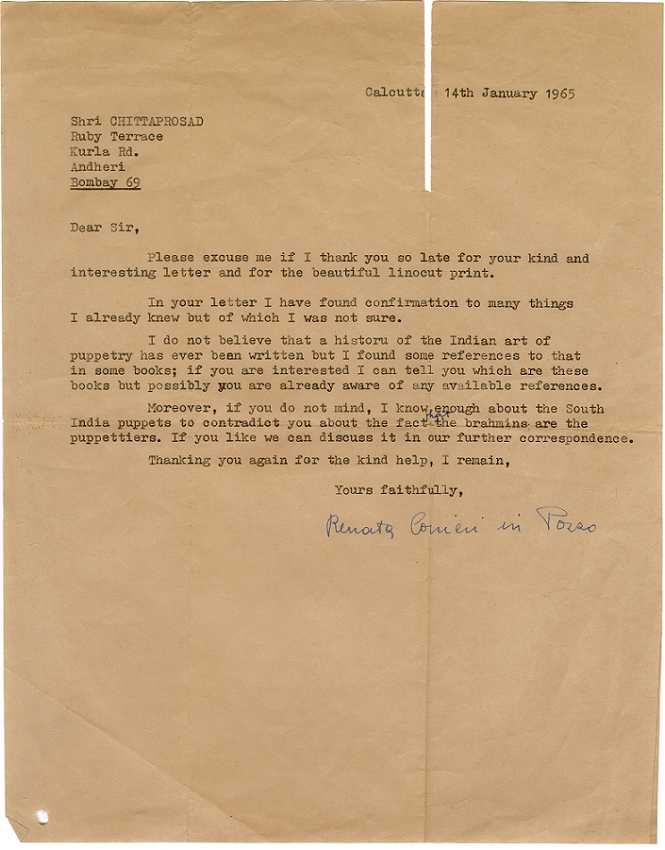

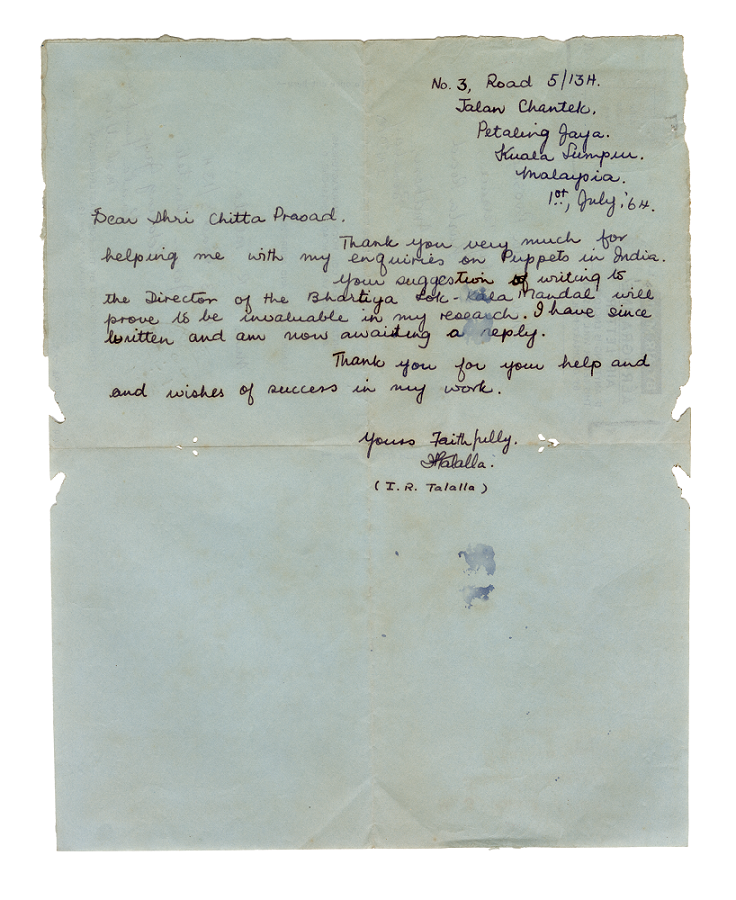

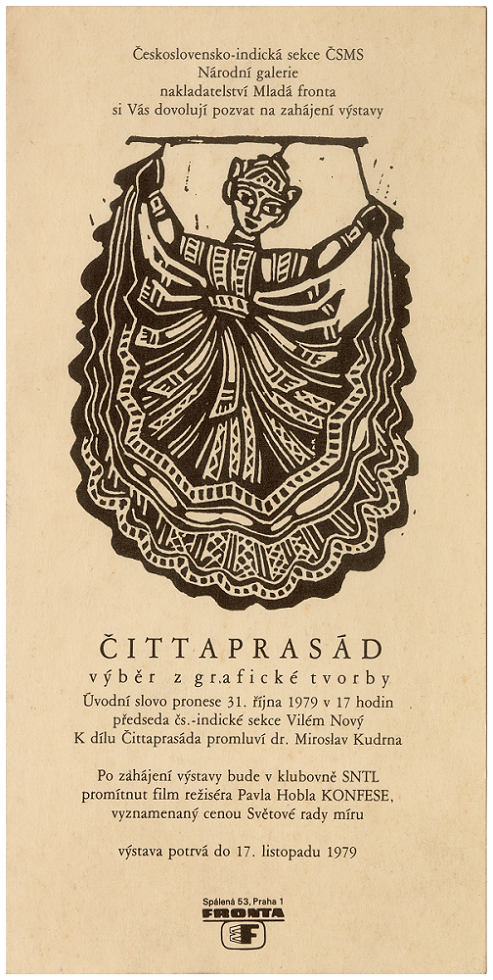

INTERNATIONAL CONNECTIONS WITH OTHER PUPPET ARTISTS Chittaprosad founded a puppet theatre group in 1957 and named it ‘Khelaghar’ (Playhouse). His experiments with puppets began around that time in his rented room in the congested working class area in Andheri, Mumbai. Although a solitary enterprise, Chittaprosad’s creations were extraordinary and attracted a lot of international attention. |

|

Chittaprosad, The Appeal, linocut on paper. |

Chittaprosad's scripts and correspondences

|

His letters from this time to his close friend Murari Gupta intimately documents Chittaprosad's growing disillusionment towards Soviet socialist politics. To put it in the more precise terms used by his contemporary Somnath Hore, they could see the 'yawning gap between socialist politics and socialist philosophies'. Therefore, in these years of self-imposed exile, Chittaprosad retreated into a solitary journey into the world of puppets. The image in the background shows a letter written by Chittaprosad on a ‘Khelaghar’ letterhead, dated 30 November, 1958, sent to friend Murari Gupta from Andheri; in the same letter the artist informed Gupta that he was about to disband ‘Khelaghar’, due to the callousness of the other two members of the troupe. We find a similar resonance in Rabindranath Tagore’s song ‘Khelaghar badhte legechhi’ (‘I have started building a playhouse’), where the poet speaks about his preoccupation with building a playhouse, which isolates him and forces him to forgo any calls from the outside world. In a later stanza, the poet says that he is building his house with whatever material is available at hand, littered or scattered around him, including fragments and stones from yesteryear—like a bricoleur. Indeed, Chittaprosad deftly put together materials from his surroundings to build his ‘Khelaghar’ (Playhouse). |

|

|

|

The artist’s later oeuvre dazzles with examples taken from the indigenous folk forms, depicting an idyllic simplicity of childhood and beauty in human relationships. Yet, in its implicit significance, they activated what Simone Wille has called 'imaginative geographies', reaching out to an audience beyond national boundaries. These artworks are not only beautiful and expressive of innocence, but also evocative of a different future—a future rooted in Chittaprosad’s lifelong vision of a just society. |

|

Greeting card printed by the artist’s sister, c. 1980s. Mechanical reproduction on paper Collection Story credits: Written by Shaon Basu |