A Tryst with Destiny: A Visual Journey

A Tryst with Destiny: A Visual Journey

A Tryst with Destiny: A Visual Journey

collection stories

|

OUR WORLD THROUGH ART A Tryst with Destiny: A Visual JourneyColonization is perhaps best understood as a process that unfolded over time than as a single historical event. In India and South Asia it began with the East India Company acquiring rights over land in different parts of the country, with the occasional political victories won on the battlefields. Since the Battle of Plassey (1757), their power over legislative and judicial matters grew steadily, backed by a strong military presence. Following the First War of Independence in 1857, the British Crown brought most parts of the Indian subcontinent under its direct rule, continuing to hold power until 1947. The Independence movement, likewise, was more than just a political event. In this story we explore different aspects of these processes—cultural, social, and political—through images in our museum and archive collection. |

Abanindranath Tagore

Mother India

Chromolithograph on paper

William Taylor

The Triumph of the Seikh Guns

Engraving on paper

Painting the Unfolding of HistoryThe defeat of Siraj-ud-Daulah to Robert Clive's forces at the Battle of Plassey (1757) is seen as a critical point in India's history, marking the ascendency of the East India Company. Paintings and prints depicting significant moments from battles—such as the victory celebrations after the Battle of Sobraon (1846)—ensured that narratives of these events told from the point of view of the British circulated across the Empire. Mostly triumphant in their tone, the stories often represented events in a sensationalist manner, justifying colonisation as a 'civilisational mission' among 'barbaric races'. |

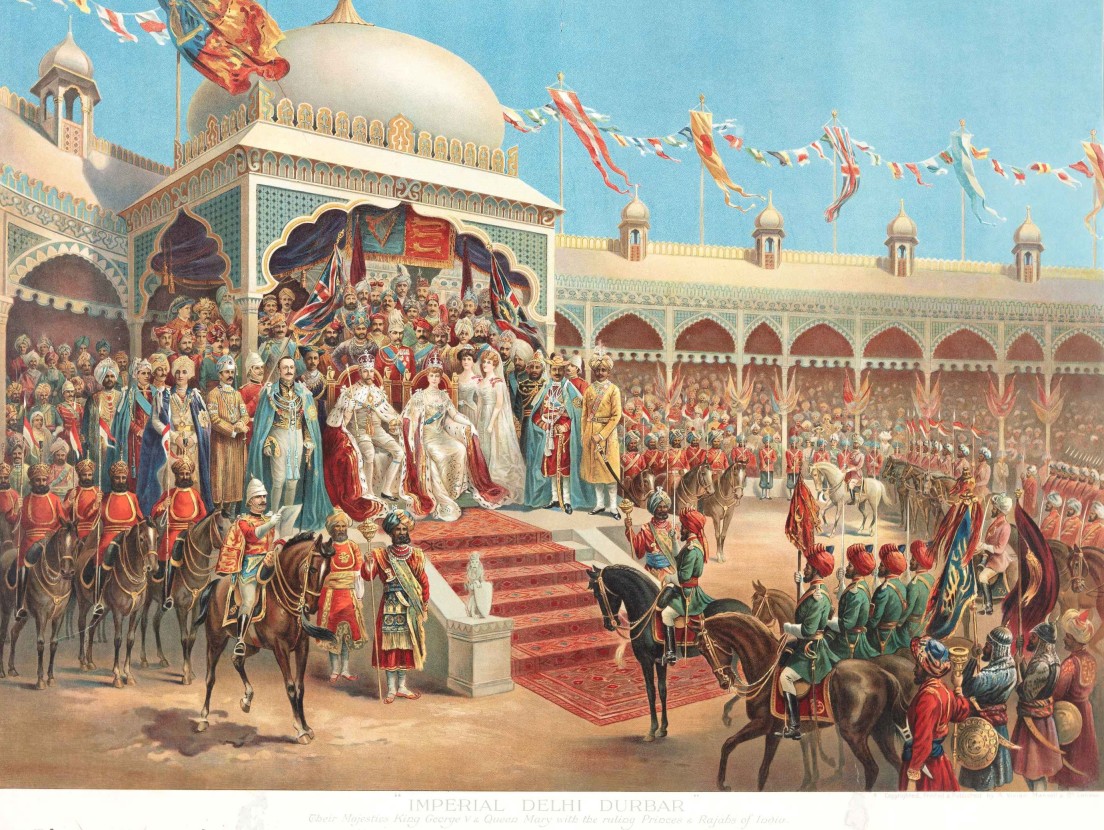

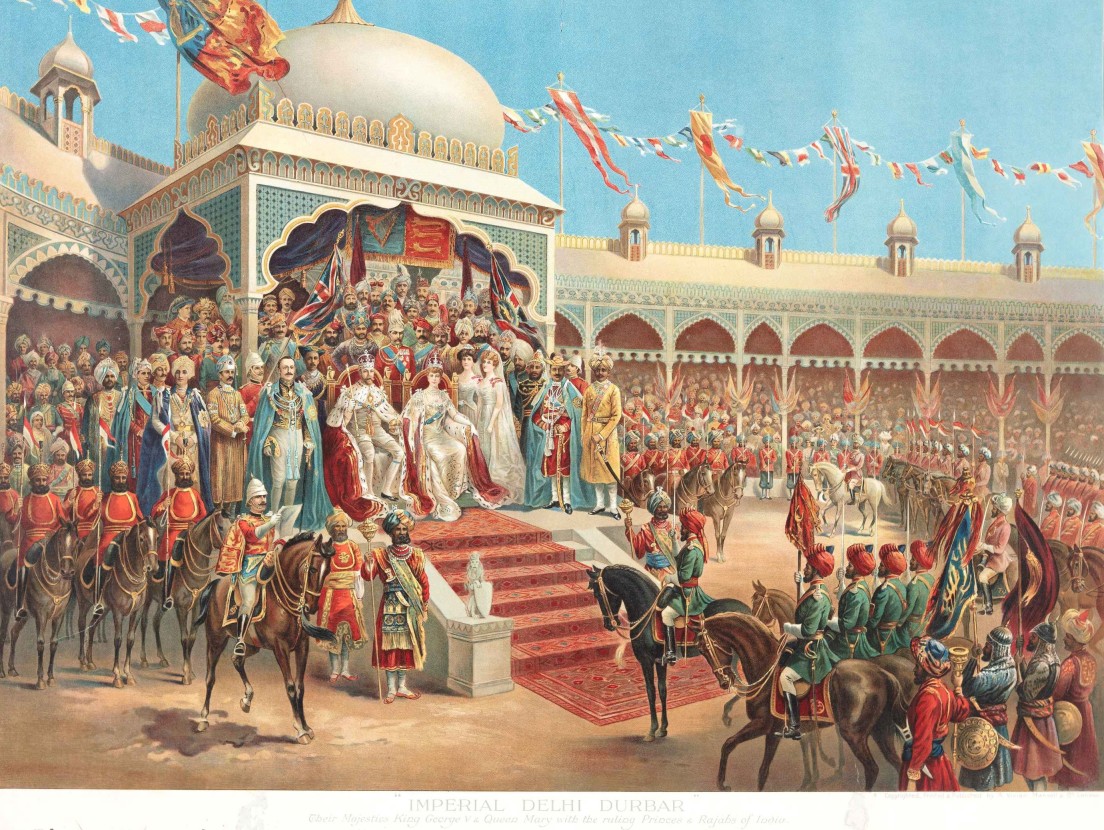

Anonymous

Imperial Delhi Durbar

Oleograph on paper

Collection: DAG

Princely States: The Gradual DissentThe relationship between the Indian princely states and the British (first the East India Company, later the Crown) underwent a significant change after the 'First War of Independence'. While formerly, the Company tried to annex their dominions aggressively, the Crown decided to strike up a more diplomatic relationship. The royal families carved a niche for themselves within the colonial framework, with some princes proactively trying to bring about progressive social changes. The Durbars at Delhi (1877, 1903, 1911) were staged by the British to ceremonially declare their political supremacy over India—and to re-assert their relationship with the princes. A few, however, dissented, either symbolically or through their support of the nationalist cause. |

F. C. Lewis

The Dussarah Durbar of His Highness Maharaja of Mysore

Anonymous

Imperial Delhi Durbar

Bourne and Shepherd

His Highness The Maharaja Gaekwar of Baroda, G.C.S.I. (from the album ‘The Coronation Durbar Delhi 1903’)

Gaganendranath Tagore

Confusion of Ideas

Lithograph on paper

Social and Cultural ResistanceBefore a politically self-conscious movement to overthrow British rule began, social reformers like Savitribai Phule (1831-1897), Fatima Sheikh (1831-?), Raja Ram Mohun Roy (1772-1833), Iswar Chandra Vidyasagar (1820-1891), among others, had started challenging orthodoxy. Driven by a vision of egalitarianism, they campaigned for women's rights, education, and equality among people. Rising literacy and the popularity of print helped public spheres evolve within the Indian polity, and these social issues were hotly debated in newspapers and periodicals, often accompanied by satirical sketches. |

Nandalal Bose

Untitled (Sati)

Gaganendranath Tagore

Confusion of Ideas

Calcutta Art Studio

Bharat Bhiksha

Chromolithograph

Figurations of WomenDescribing Abanindranath Tagore's representation of Bharat Mata (Mother India) as a picture that appeals to every Indian heart, Sister Nivedita wanted it printed in 'tens of thousands' so every individual could possess a copy. Queen Victoria herself, seen by many Indians as a benevolent figure, was represented as Bhartiswari (Empress of India). Although many women were at the forefront of anti-colonial movements, they were more often represented in iconography by male authors, artists, and politicians, giving rise to idealised depictions. This section looks at a few examples of how figurations of women changed over time. |

Calcutta Art Studio

Bharat Bhiksha

Abanindranath Tagore

Mother India

Anonymous

Untitled

Anonymous

Untitled

Offset print on paper

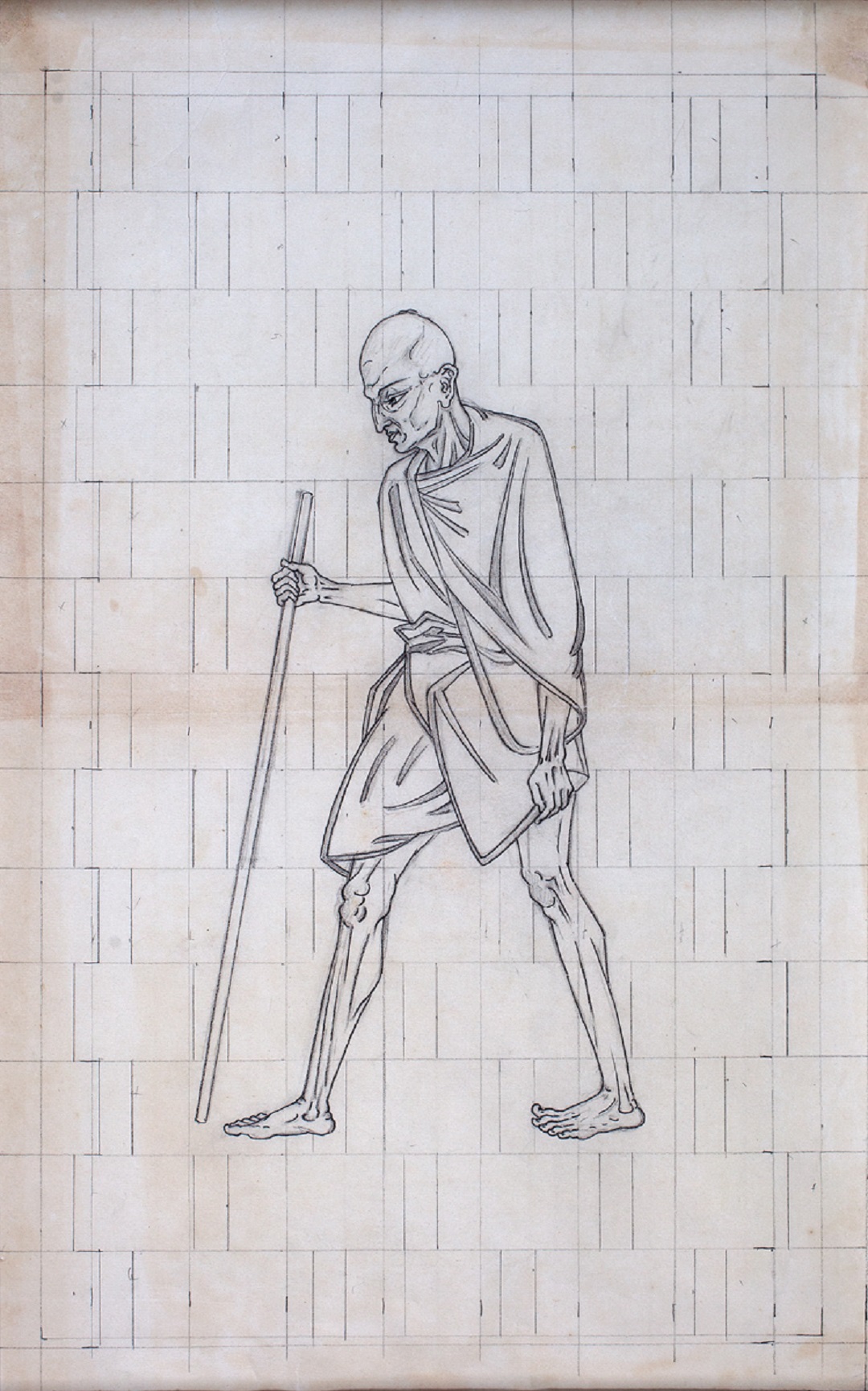

The Freedom Movement in the Popular ImaginationIndia's nationalist leaders and artists understood the importance of creating iconic images that captured the imagination of the people, enabling mass mobilisation against colonial rule. The printed picture played an important role in popularising these images, and later public sculpture too shouldered part of this responsibility. This section looks at some of the iconic images that helped visualise critical moments during the freedom struggle. |

Nandalal Bose

Untitled (Bapuji)

Nandalal Bose

Standing figure under a Kadam tree

Anonymous

Untitled

Somnath Hore

Quake Victim

Lithograph on paper

World War II and the Bengal FamineIn the last ten years of British rule in India two events—apart from the on-going political campaigns—revealed the coloniser's indifference to Indian lives. The first was the unilateral co-option of India in World War II, and the second was the human-made Bengal famine of 1942-43, that resulted in the loss of millions of lives. |

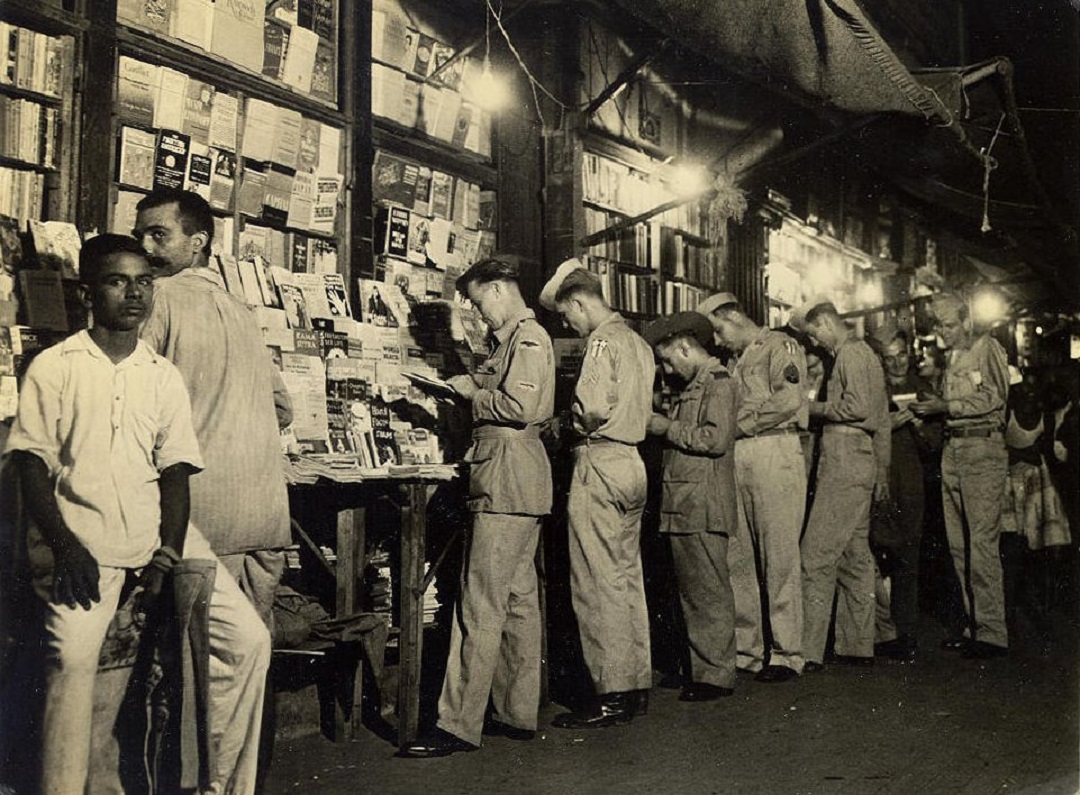

Clyde Waddell

Untitled

Caption: 'Corner bookstalls, specializing in lurid novels, sec treatises, are fascinating spots for British and American soldiers alike. Typical titles, "The Escapades of Erotic Edna", "Kama Sutra, The Hindu Art of Love".'

Collection: DAG

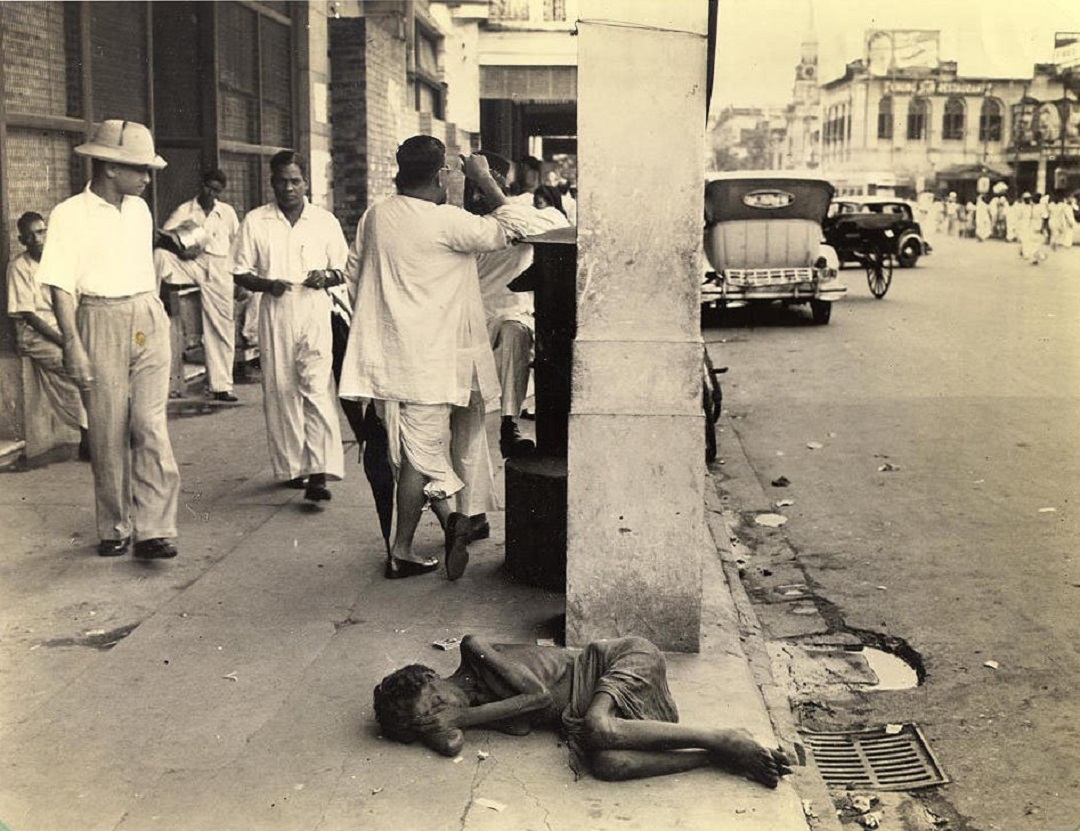

Clyde Waddell

Untitled

Caption: 'The indifference of the passerby on this downtown Calcutta street to the plight of the dying woman in the foreground is considered commonplace. During the famine of 1943, cases like this were to be seen in most every block, and though less frequent now, the hardened public reaction seems to have endured.'

Collection: DAG

Clyde Waddell

Untitled

Caption: 'These Sikh lads have chosen an auspicious stand for their business of selling 'precious' stone to GI's. No more than 12 years old, these boys are shrewd and 'malum' English well enough to trim a sucker every time.'

Collection: DAG

A Yank's Memories of CalcuttaFrom 1943 to '45 Clyde Waddell served as personal photographer to Lord Mountbatten. In February 1945, the former Houston Press employee, joined a magazine that was launched by the Allied forces, titled Phoenix. He found himself in Calcutta, which had been of critical strategic importance, with the British fearing an attack from Japan. The city that we see through Waddell's lens was ravaged in the aftermath of the war and the famine. His photographs also reveal the activities of other GIs posted in the city, spectacular aerial views, and some of Calcutta's charming peculiarities, which he describes in over-exoticised terms in his detailed captions. |

Chittaprosad

Purna Shashi

Brush and ink on paper

Zainul Abedin

Untitled

Woodcut newsprint on paper

Visualising the Bengal FamineApart from the lives that were lost in concentration camps or at the war front, effects of World War II were felt by common people across the world. Bengal was no different. Following a cyclone in late 1942, it witnessed one of the most devastating famines in its famine-ridden history, where over two million people lost their lives. It is widely accepted today that the famine's effects could have been controlled but for the policies of the British, who got India involved in the war, and then refused to distribute food grains equitably. Artists, mostly of the Communist Party, began travelling to the villages to document the horrors that were playing out. Chittaprosad, Somnath Hore, and Zainul Abedin are among those who responded to this grave injustice through their art, using their own individualistic styles. |

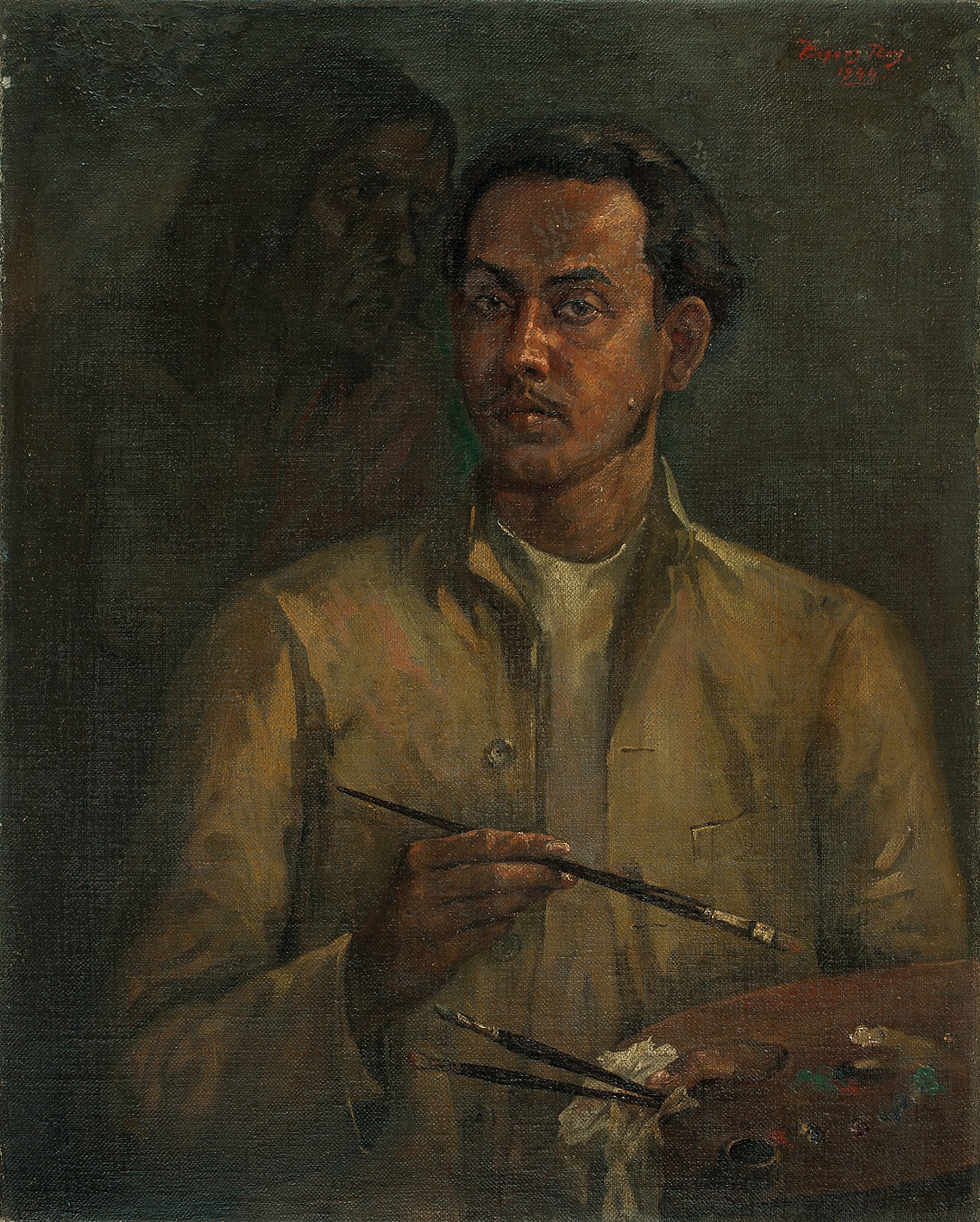

Kisory Roy

Art and Famine (Self Portrait)

Oil on canvas

Looking Back through ArtArtists responded in different ways to the social, cultural, and political changes that led up to, but continue beyond, that decisive day in August 1947. Some responded to the political moment, creating enduring images that shaped public responses. Others sought freedom through and in art, asking what it would mean to find a truly modern visual idiom and forms of expression. Credits |

Your Views

|

We are always interested in learning more about our collection from viewers like you. If you have any information or interpretation you would like to share, please let us know below. What do you think these three figures are meant to convey about the relationship between England, India, and India's subjects? Do you think it aligns with how we understand our relationship with the colonial past today? |