A Home for Goddess Kali: Exploring Kalighat with Deonnie Moodie

A Home for Goddess Kali: Exploring Kalighat with Deonnie Moodie

A Home for Goddess Kali: Exploring Kalighat with Deonnie Moodie

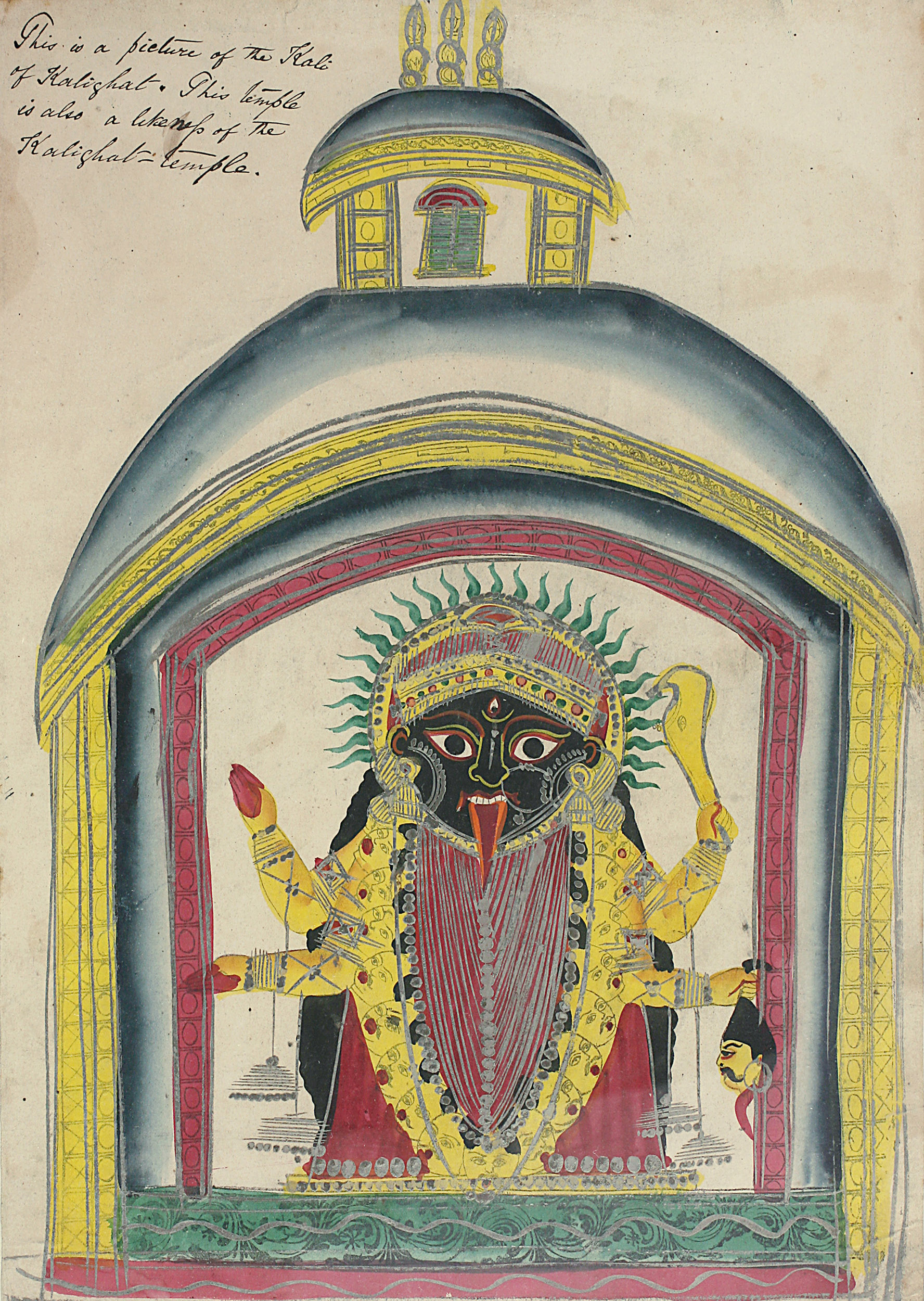

Unidentified Artist (Kalighat Pat), Dakshinakali (detail), Watercolour and gouache on paper, late 19th century, 19.5 × 15.5 in. Collection: DAG

Deonnie Moodie teaches at the Department of Religious Studies at the University of Oklahoma. Her book The Making of a Modern Temple and a Hindu City: Kalighat and Kolkata explores the temple complex of Kalighat and its evolving relationship with the neighbourhood around it, including the city of Kolkata.

It examines the modernisation of the Kalighat temple and its administration, as well as the associated historical, legal, and physical processes that helped create such a modern narrative for the temple. Her research also juxtaposes and analyses the modernisation efforts undertaken by different class groups, including the middle class and lower class populations, and the resulting conflicts and resistance. She spoke to the editor of the DAG Journal about the significance of the neighbourhood for a modern Kolkata, and its contribution to the myth of Kali.

|

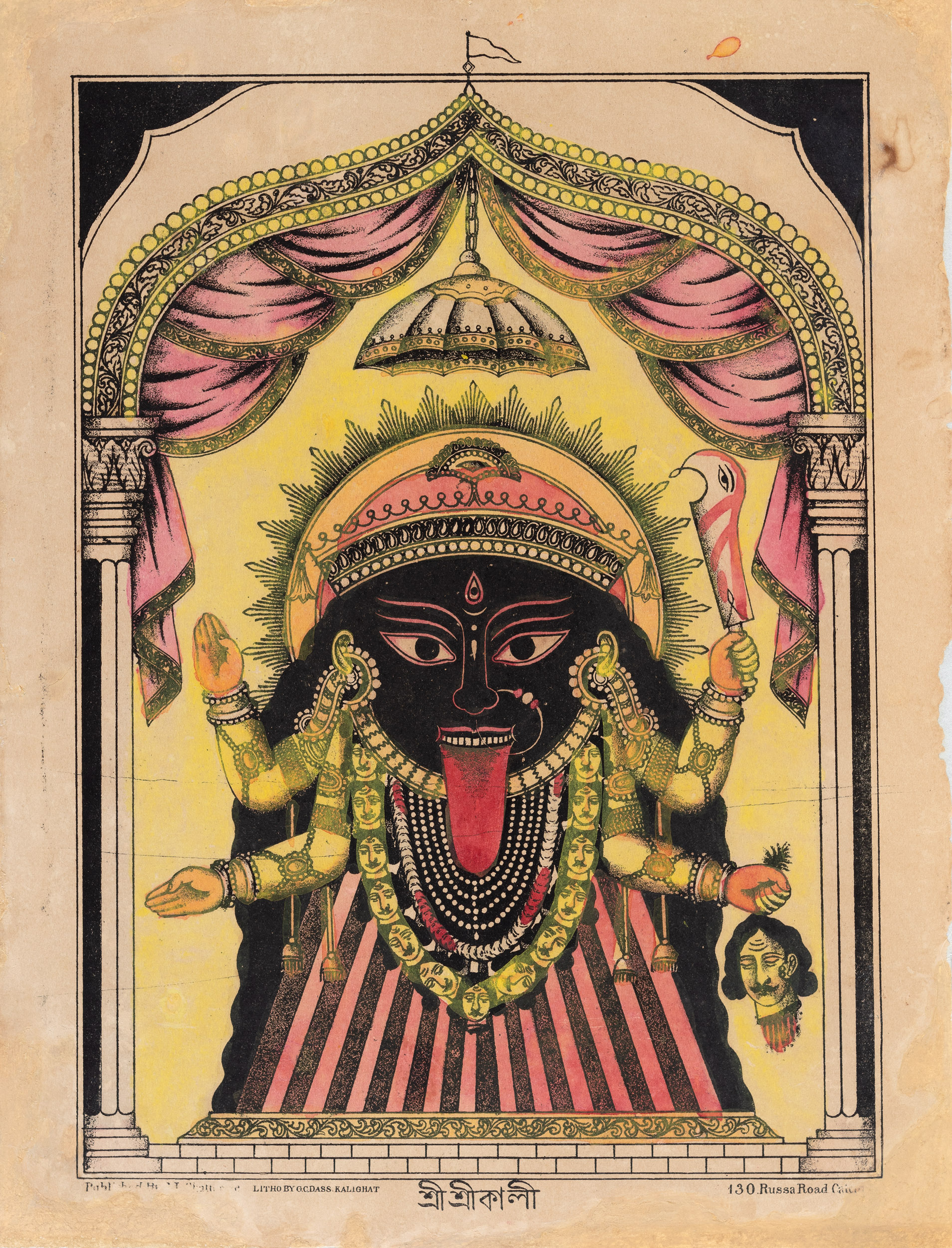

Unidentified Artist (P. C. Biswas), Shri Shri Kali Mata, Lithograph tinted with watercolour on paper, late 19th century, Print Size: 9.7 × 7.5 in., Collection: DAG |

Q. Why was Kalighat rejected or reviled by many Indian (and British) intellectuals and reformers, and critics of colonialism, even though Kali worship was encouraged? What were the popular associations one tended to have about Kalighat until the end of the nineteenth century?

Deonnie Moodie: The central motivation driving my book on Kalighat arises from my interest the world of the Bengali bhadralok and exploring the nuances of the Bengali renaissance during the nineteenth century in Calcutta. It was a period of fascinating transformation, where Hindu forms underwent profound revisions and reinterpretations. The juxtaposition of the revered Kalighat temple against the backdrop of Hindu reform movements intrigued me immensely.

Kalighat, despite its significance as a prominent temple in Calcutta, was often reviled by Hindu reformers. It embodied everything they sought to reform: polytheism, iconoclasm, and unrefined forms of worship. The temple's depiction of the goddess Kali with her elongated tongue, holding severed heads, and adorned with skulls epitomized a form of worship that clashed with the sanitized versions propagated by reformers.

Daily animal sacrifices, still practiced at Kalighat, further fuelled its notoriety among reformers and colonial administrators alike. Figures such as Vivekananda, despite being raised by a Shakta mother who frequented Kalighat, notably omitted any mention of the temple in their works—a silence that speaks volumes about societal perceptions.

However, Kalighat held a paradoxical position in society. Despite its vilification, it was acknowledged as a potent site of power, a place where devotees sought miracles and interventions. This duality underscores a broader societal dichotomy: the powerful often exist outside the bounds of respectability, especially within the confines of the bhadralok ethos.

The temple's reputation as a site of power was intertwined with its perceived danger, stemming from its associations with blood and ritualistic fervour. Simultaneously, scholars like (Rachel F.) McDermott highlight Kali's portrayal as a nurturing mother figure, embodying a fierce matriarchal energy that defies conventional expectations.

In essence, Kalighat emerges as a microcosm of the complexities inherent in Indian society—a place where tradition and modernity, reverence and revulsion, converge in a tapestry of contradictions. Exploring these intricacies not only sheds light on the evolving dynamics of religious expression but also unveils deeper insights into the cultural fabric of Bengal and beyond.

|

Unidentified Artist (Kalighat Pat), Dakshinakali, Watercolour and gouache on paper, late 19th century, 19.5 × 15.5 in. Collection: DAG |

Q. What were the ‘modernist, aesthetic compulsions’ that drove Indian reformers of Kalighat? How do we see it play out in the organization of the temple and its neighbouring space over the twentieth century—especially through those court cases you’ve so closely followed?

Deonnie: The significance of the twentieth-century court cases lies in their pivotal role in empowering reformers to enact changes within the physical confines of the temple. My book underscores that while late nineteenth-century reformist efforts aimed to reshape the temple's historical narrative, they also sought to challenge entrenched British interpretations of Calcutta's history. Kalighat, in this context, served as a focal point for Bengali historians striving to reclaim the city's narrative from colonial distortions.

Although late nineteenth-century narratives didn't extensively address the temple's physical space, the later part of the twentieth century witnessed a marked shift towards concerted efforts to revitalize it. These efforts, essentially rooted in gentrification, were spearheaded by individuals cognizant of Kalighat's status as a tourist attraction and sought to transform it into a pristine monument worthy of pride.

The intensified focus on the temple's aesthetics mirrored Calcutta's aspirations to assert itself within the global arena of prominent cities. Bengalis, contemplating the city's global image, questioned why Kalighat couldn't rival iconic landmarks like the Victoria Memorial (which was finished in 1921). Despite Bengalis' disdain for Queen Victoria, they couldn't help but acknowledge the meticulous upkeep of her memorial—a stark contrast to the neglect Kalighat faced.

Reformers advocated for elevating Kalighat to a comparable stature, leveraging local resources and capabilities to enhance its significance and beauty. This juxtaposition between Kalighat and the Victoria Memorial highlights broader debates about cultural pride, resource allocation, and the reclamation of heritage within a rapidly evolving urban landscape.

|

Atul Bose, Victoria Memorial, Calcutta, 1923, Oil on cardboard, 15.5 x 24.5 in. Collection: DAG |

The evolution of Kalighat, thus, reflects the complex nature of societal transformation and urban development, where historical narratives intersect with contemporary aspirations for progress and identity. By going into these narratives, my book seeks to unravel the interplay of tradition, modernity, and agency shaping the physical and cultural landscapes of Calcutta.

One of the primary outcomes of these revitalisation efforts is the gradual removal of hawkers, beggars, and even the pandits from the temple premises. Among the Brahmins operating within the temple hierarchy, the pandits play a crucial role in guiding pilgrims, conducting rituals, and facilitating temple visits. Despite concerted efforts, the physical presence of these individuals remains entrenched around the temple area due to the sheer number of livelihoods dependent on it. The dense crowds and perceived disorderliness created by this presence pose significant challenges for aesthetic reformers striving to project a sanitised image of the temple.

Moreover, the sight of blood on the temple floor presents another obstacle for reformers. Instead of advocating for the eradication of animal sacrifice—a practice deeply ingrained in Kalighat's traditions—the focus shifts towards containment. Early depictions from the nineteenth century reveal an absence of physical enclosures around the sacrificial area. However, over the course of the twentieth century, the emergence of enclosures with heightened walls, often reaching six or five feet, becomes increasingly evident. These enclosures, characterized by intricate lattice work, serve to obscure the sight of blood from passersby who may find it objectionable. By shielding the sacrificial rituals from public view, reformers hope to mitigate discomfort and maintain a semblance of cleanliness and order within the temple precincts.

|

Kalighat temple in Kolkata. Image courtesy: Wikimedia Commons |

Q. In their efforts to modernize the temple during the colonial period, how did the reformers employ visual tools like maps, photographs and artworks? Were they similar to how they employed ‘rational’/scientific historiographical methods?

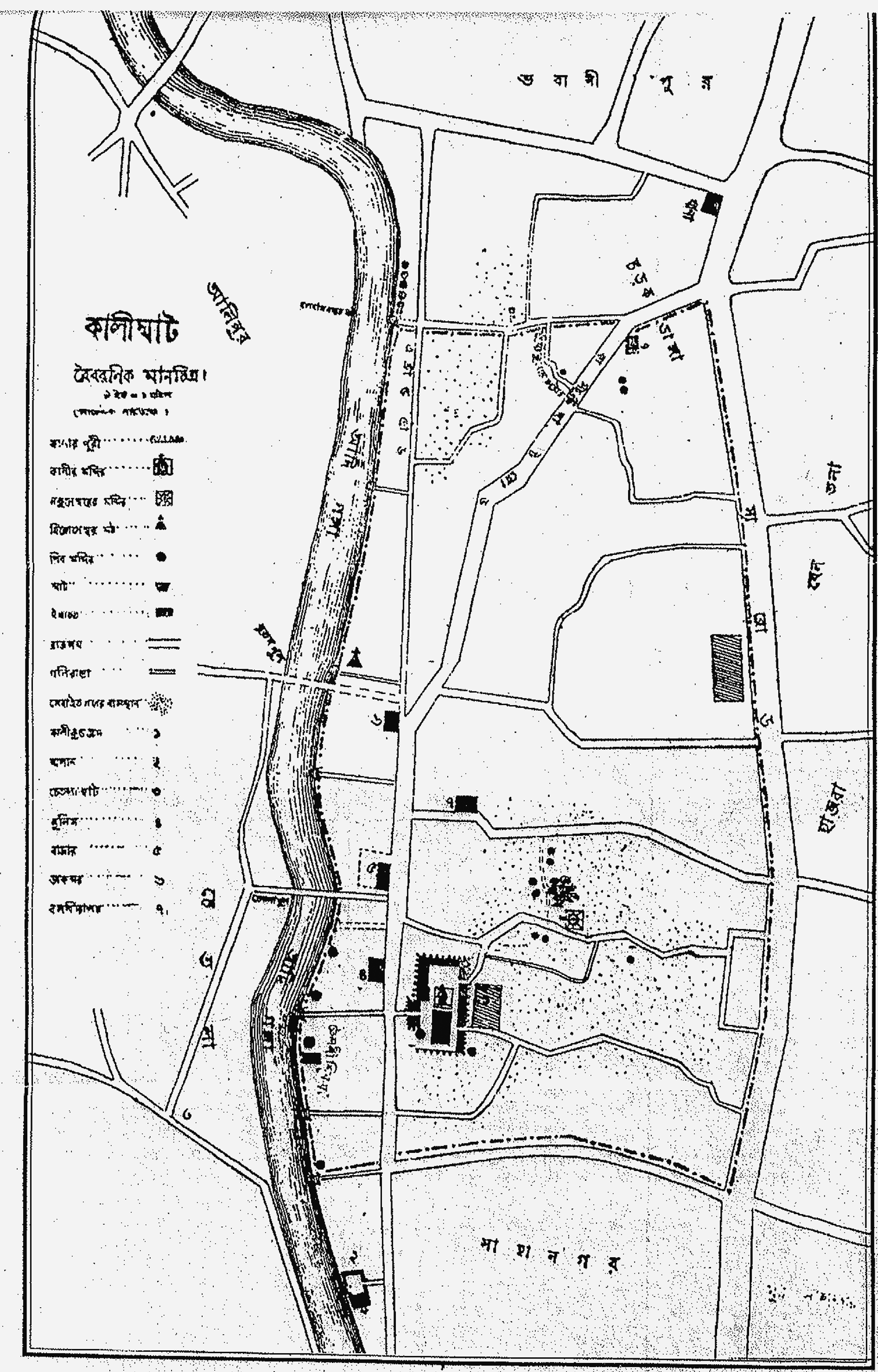

Deonnie: The use of maps emerged as a fascinating aspect of the story that I initially overlooked in my research. While maps are referenced in the text, their visual significance in knowledge production didn't immediately register. I find that the four Bengali historians I write about in the initial chapter, who notably contributed to establishing Calcutta's foundational narrative around the worship of Kali, by positioning it in contrast to the British narrative emphasising monumental architecture and wide thoroughfares, employed these tools quite interestingly.

For instance, Gaur Das Bysack's famous piece in the Calcutta Review, ‘Kalighat and Calcutta,’ became a cornerstone reference during my research. Bysack’s endeavour to map Calcutta within Aryavarta, the ancient land of the Aryans, underscores his quest to reclaim historical space. While Bysack posits Kalighat's origins in the fifteenth century, he encounters challenges in integrating it into the Aryavarta map, yet his intent is clear—to situate Kalighat within broader historical contexts.

|

Map of the Kalighat Neighborhood Circa 1891, used in Surjyakumar Chattopadhyay's book, Kalikshetra Dipika (A Commentary on the Land of Kali). Image courtesy: Archive.org |

Similarly, A. K. Ray’s depiction of pre-European Calcutta maps the foundational villages—Sutanuti, Gobindapur, and Kolikata—while attempting to contextualise Kalighat's historical position. Surjyakumar Chattopadhyay's 1891 work, "Kālīkṣetra Dīpikā (A Commentary on the Land of Kālī)," explores the Kalighat neighbourhood, mapping its thoroughfares, waterways, and sacred sites. Each historian grapples with the spatial and temporal significance of Kalighat, striving to articulate its centrality within Calcutta's evolution.

Their rational, scientific approach to spatial analysis underscores the intricate relationship between space and significance. Through meticulous argumentation, they assert Kalighat's pivotal role in shaping Calcutta's narrative trajectory, ultimately concluding that its presence is integral to the city's developmental arc.

The Bengali historians are frequently advocating for the centrality of their own families within this narrative and their connection to the city's genesis. The notion that it originated in Gobindopur by their family's hand and then migrated southward is captivating. Does it hold water? I believe it holds its ground as effectively as any British histories of the era. They're all crafting a narrative where their lineage takes precedence, defining 'their people' in varied ways. The city's history isn't inherent; it's a construct that requires shaping. For British historians to assert Job Charnock's 1690s landing as the city's foundation is also a construct—a claim to significance and foundation. Similarly, figures like Bysack and Prankrishna Datta are engaging in a similar narrative construction, asserting the importance of their lineage in shaping the city's trajectory.

|

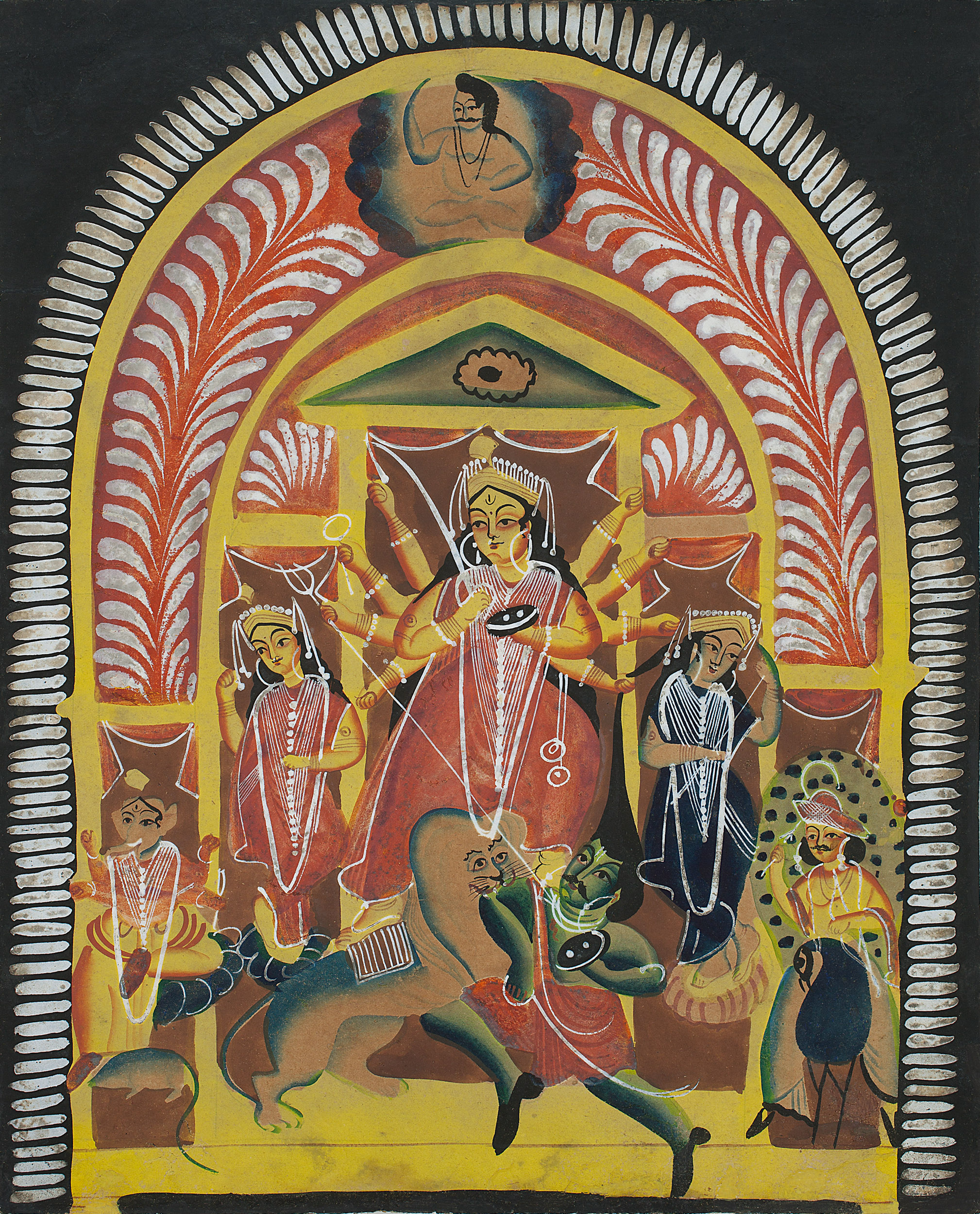

Anonymous (Kalighat Pat), Untitled (Durga Pujo), Water colour and gouache on paper pasted on cardboard. Collection: DAG |

On the Sabarna Roy Chowdhury family’s claim to prior ownership (and foundation) of Calcutta:

Since they were the ones responsible for constructing the temple structure in 1809, the Sabarna Roy Chowdhury family holds a special claim to its legacy. It's an empowering narrative, emphasizing the importance of their history over British colonial narratives. However, I also want to recognise diverse narratives within the city's tapestry, and not let this one take over all the others. Calcutta is renowned for its cosmopolitanism, encompassing Muslim, Armenian, Jewish communities, among others. While they may not assert their histories in the same manner, it doesn't diminish their connection to the city. This is why I titled the book The Making of a Modern Temple and a Hindu City: Kalighat and Kolkata. It highlights the Hindu-centric narrative being constructed, but it doesn't negate the city's cosmopolitan history. Even if it isn't solely a British city, it doesn't necessarily translate to a Hindu city. It's a dynamic metropolis, reflecting a myriad of cultural influences and identities.

Q. You have noted the difficulty in reconstructing the critique or historical views of lower class and lower caste populations who lived around Kalighat on modern reform projects. How do non-literary sources, especially art and craft objects, like Kalighat pats, help discern the nature of their ideas about life in Kalighat and Kolkata?

Deonnie: Scholars like Jyotindra Jain and Tapati Guha-Thakurta have explored these questions in some depth. My focus centred on Kalighat as a hub of reform movements, so I didn't look too deeply into the case of the Patuas. However, it's known that they began congregating at Kalighat in the early to mid-nineteenth century, coinciding with its burgeoning status as a pilgrimage site. Pilgrimage sites naturally foster economic activity, amplified by the extension of the tram line from central Calcutta to Kalighat, easing travel and commerce. The emergence of a red-light district around Kalighat is also noteworthy, a phenomenon observed in many pilgrimage destinations due to increased visitor traffic.

|

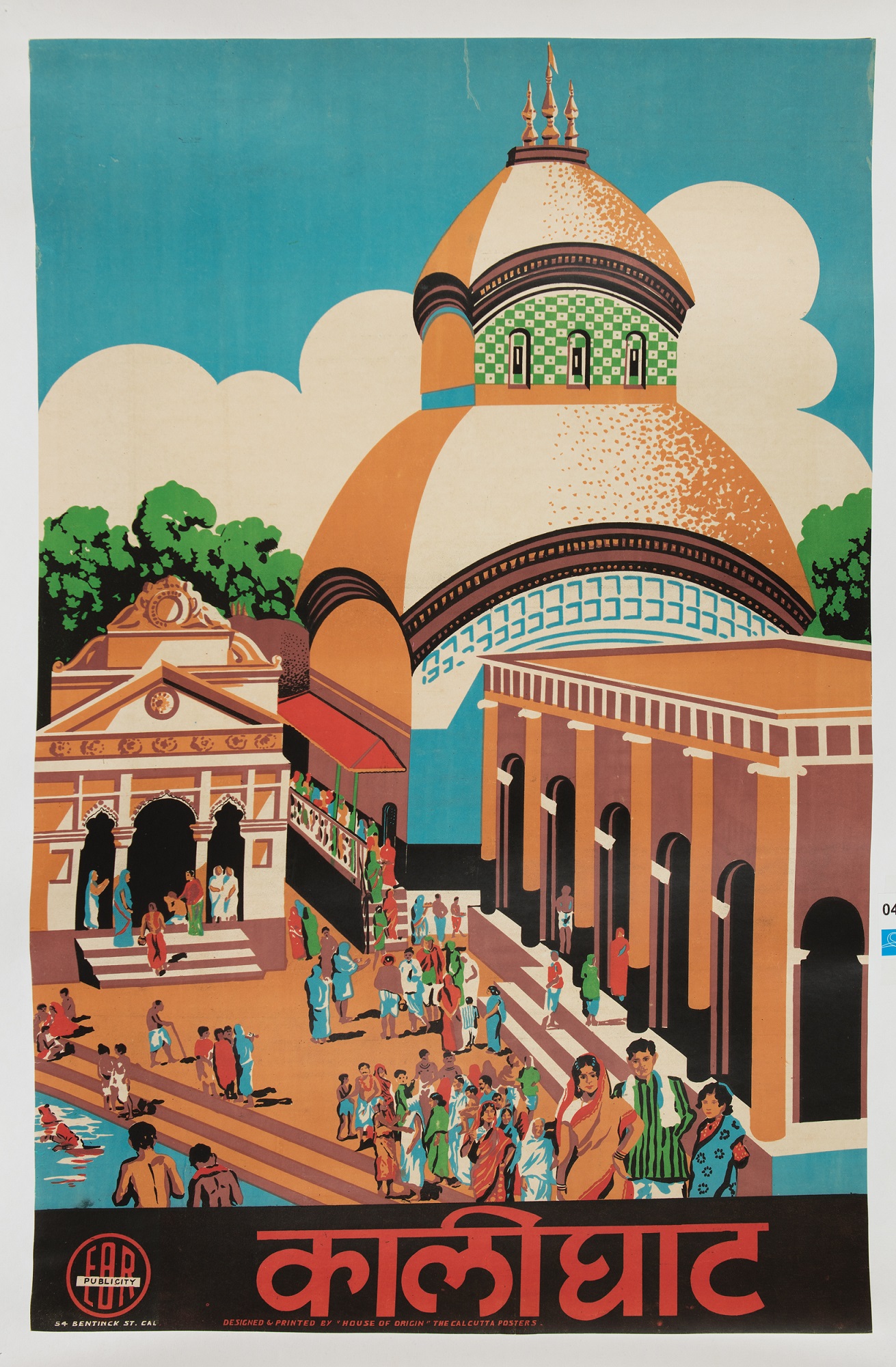

Unidentified artist, Kalighat, Chromolithograph on paper pasted on canvas. Collection: DAG |

The Patuas' artistic brilliance is evident not only in their visually stunning artwork but also in their satirical commentary on Babu and Bhadralok culture. They were particularly critical of those adopting European values, attire, and mannerisms. It's reasonable to assume they would express similar scepticism towards such influences at Kalighat. Their satirical lens likely scrutinized any attempts to assimilate European customs and narratives into the fabric of Kalighat's cultural landscape.

It certainly underscores the significance of the proliferation of these beautiful images of Kali, which I'm certain will be featured in your exhibit. These depictions encapsulate the essence of what the Patuas hold dear—beauty and artistic expression. It suggests that Kalighat, both in its physical space and the community surrounding it, served as a form of critique against the hegemony of white European Calcutta. This aspect, illuminated by the Patuas' work, offers valuable insights into the multifaceted nature of Kalighat and its broader socio-cultural implications.

|

Anonymous, Untitled, Water colour, colloidal tin and graphite on paper. Collection: DAG |